The Finnish Open Dialogue Approach to Crisis Intervention in Psychosis: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An "Authentic Wholeness" Synthesis of Jungian and Existential Analysis

Modern Psychological Studies Volume 5 Number 2 Article 3 1997 An "authentic wholeness" synthesis of Jungian and existential analysis Samuel Minier Wittenberg University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Minier, Samuel (1997) "An "authentic wholeness" synthesis of Jungian and existential analysis," Modern Psychological Studies: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps/vol5/iss2/3 This articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals, Magazines, and Newsletters at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Psychological Studies by an authorized editor of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An "Authentic Wholeness" Synthesis of Jungian and Existential Analysis Samuel Minier Wittenberg University Eclectic approaches to psychotherapy often lack cohesion due to the focus on technique and procedure rather than theory and wholeness of both the person and of the therapy. A synthesis of Jungian and existential therapies overcomes this trend by demonstrating how two theories may be meaningfully integrated The consolidation of the shared ideas among these theories reveals a notion of "authentic wholeness' that may be able to stand on its own as a therapeutic objective. Reviews of both analytical and existential psychology are given. Differences between the two are discussed, and possible reconciliation are offered. After noting common elements in these shared approaches to psychotherapy, a hypothetical therapy based in authentic wholeness is explored. Weaknesses and further possibilities conclude the proposal In the last thirty years, so-called "pop Van Dusen (1962) cautions that the differences among psychology" approaches to psychotherapy have existential theorists are vital to the understanding of effectively demonstrated the dangers of combining existentialism, that "[when] existential philosophy has disparate therapeutic elements. -

Letters of Psychotherapy the NORDIC PSYCHIATRIST

THE NORDIC PSYCHIATRIST Issue 1 2017 Letters of Psychotherapy THE NORDIC PSYCHIATRIST Letters of psychiatry Psychotherapy is one of the most used treatment methods in modern psychiatry. Treatment through verbal communication has been used through the centuries as medics, philosophers, and spiritual practitioners have used psychological methods to heal others. The term psychotherapy derives from ancient Greek “psyche”, meaning spirit or soul and “therapeia” meaning healing or medical treat- ment. A modern definition of psychotherapy would be "treatment of disorders of the mind or person- ality by psychological methods”. Not too long ago, a clinician in psychiatry was expected to choose sides regarding how he or she conceptualised psychiatry, both in terms of diagnosis and treatment. The two standpoints were either the “biological one” – or the “psychotherapeutic one”. The latter was synonymous with the practice of insight-oriented therapies, with the focus on revealing or interpreting unconscious processes. The relief of symptoms was not the main focus of the treatment, but to unveil the unconscious conflict. For years, psychodynamic therapy was the only therapy of choice. With time new methods arose, and were scientifically evaluated. As the concept of evidence entered the stage, psychodynamic practi- tioners were challenged by therapists using cognitive-behavioural and systemic techniques. Over the last decades, numerous therapies have been introduced. Initially, psychotherapy was performed by doctors. Over the years, psychologists have become more or less synonymous with psychotherapy. Today, fewer doctors are trained as psychotherapists, and it is often debated to which degree psychotherapy should be a part of specialist training in psychiatry. Earlier assumed harmless, the potential side effects of psychotherapy are nowadays highlighted in a new way, comparing them with drug therapy. -

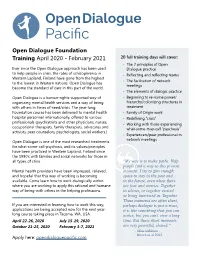

Open Dialogue Foundation Training April 2020

Open Dialogue Foundation Training April 2020 - February 2021 20 full training days will cover: • The 7 principles of Open Ever since the Open Dialogue approach has been used Dialogue practice to help people in crisis, the rates of schizophrenia in • Reflecting and reflecting teams Western Lapland, Finland have gone from the highest • The facilitation of network to the lowest in Western nations. Open Dialogue has meetings become the standard of care in this part of the world. • The elements of dialogic practice Open Dialogue is a human-rights-supported way of • Beginning to re-name power/ organizing mental health services and a way of being hierarchy/colonizing structures in with others in times of need/crisis. The year-long treatment Foundation course has been delivered to mental health • Family of Origin work hospital personnel internationally, offered to various • Redefining “crisis” professionals (psychiatrists and other physicians, nurses, • Working with those experiencing occupational therapists, family therapists, advocates and what-some-may-call “psychosis” activists, peer counselors, psychologists, social workers.) • Experiencers/peer professional in network meetings Open Dialogue is one of the most researched treatments for what-some-call-psychosis, and its values/principles have been practiced in Western Lapland, Finland since the 1980’s with families and social networks for those in all types of crisis. “My way is to make paths. Help people find a way to this present Mental health providers have been impressed, relieved, moment. I try to give enough and hopeful that this way of working is becoming space to stay in the past and available. Come learn how to work dialogically within in the future, even when there where you are working to apply this rational and humane are fear and worries. -

ISPS 2015 Presenter Database

HIT (Hallucination Focused Integrative Therapy): Preferred for AVH? Jack Jenner MD, PhD Bert Luteijn MD Wednesday, March 18 10:00-4:00: 5 contact hours Preconf 1 Learning Objectives: Describe HIT methodology, its implementation, and its results List possibilities and pitfalls of integrating interventions with different backgrounds Discuss special motivational strategies developed for this patient population. Compassion Focused Therapy for Recovery After Psychosis Christine Braehler DClinPsy Wednesday, March 18 10:00-4:00: 5 contact hours Preconf 2 Learning Objectives: Describe the basic principles and practices of CFT Discuss research on emotion regulation and CFT in psychosis Explain the CFT model of recovery after psychosis Describe group-based protocol Practice compassion-focused skills (imagery, reframing, mentalizing) Psychosis and sexual abuse: psychotherapy and art therapy Maurizio Peciccia MD Wednesday, March 18 10:00-4:00: 5 contact hours Preconf 3 Learning Objectives: Define three core aspects of progressive mirror drawing in psychosis treatment List three important aspects of the use of aquatic therapy for persons with a psychotic disorder Define the evidence base for the use of both progressive mirror drawing and aquatic therapy in psychotic disorders Recovery & Psychosis Larry Davidson PhD Wednesday, March 18 10:00-4:00: 5 contact hours Preconf 4 Learning Objectives: List three important characteristics of peer support in schizophrenia List three different definitions of recovery in schizophrenia List three reasons why peer support is important to recovery from schizophrenia The Gnosis of Psychosis: A Critical Media Viewing Project Keris Myrick MBA, MS Wednesday, March 18 10:00-4:00: 5 contact hours Preconf 5 Learning Objectives: Define the importance of how psychosis is displayed in the popular media State main ethical principles concerning portrayal of psychosis in the media Apply ethical principles to how they represent psychosis in the media and in their publications. -

Opening-Dialogues-September-2021.Pdf

& Open(ing) Dialogues 2-day online international workshop An invitation to explore dialogical ways of working in mental health and social crises “The great gift of being heard and received“ New Date: AUTUMN 2021 - Bettina, a recent trainee 9 & 10 September 2021 The need to be heard and responded to is fundamental to us as human beings. Yet, in health and social care 9am - 5pm BST (UK/Ireland) services we are often focused more on what we can do (8am - 4pm UTC, 10am - 6pm CEST) when someone in crisis as opposed to how we can truly ‘be with’ them and their loved ones. Whilst this approach has its merits, many of us can easily recall times where This is an invitation to ... those we have wished to help have left feeling unheard, ✻ Explore what it means to be ‘in dialogue’ with others disconnected and/or harmed. and what this might o er in our lives and work Open Dialogue is an approach that originated Western ✻ An embodied experience of dialogic relating – Lapland where system, philosophy and practice have listening and responding to self and others been developed to complement and support the ✻ Learn more about dialogic approaches to mental nurturing of dialogue between people in crisis situations. health and social crises, and some of the di erent It has gained an increasing following across the world, ways these have been implemented around the world. with proponents being excited by its outcomes and the way in which this approach fi ts within an ethical, trauma ✻ An opportunity to connect with others, creating informed and human rights-based way of working. -

“Make 'Em Laugh” the Interaction of Humor in the Therapeutic Treatment of Trauma: a Narrative Review

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota St. Catherine University Social Work Master’s Clinical Research Papers School of Social Work 2018 “Make ’em Laugh” The nI teraction of Humor in the Therapeutic Treatment of Trauma: A Narrative Review Katherine Goodman University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/ssw_mstrp Part of the Clinical and Medical Social Work Commons, and the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Goodman, Katherine, "“Make ’em Laugh” The nI teraction of Humor in the Therapeutic Treatment of Trauma: A Narrative Review" (2018). Social Work Master’s Clinical Research Papers. 860. https://ir.stthomas.edu/ssw_mstrp/860 This Clinical research paper is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Social Work at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Social Work Master’s Clinical Research Papers by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Head: “MAKE ‘EM LAUGH” 1 “Make ’em Laugh” The Interaction of Humor in the Therapeutic Treatment of Trauma: A Narrative Review by Katherine Goodman, B.S. MSW Clinical Research Paper Presented to the Faculty of the School of Social Work St. Catherine University and the University of St. Thomas St. Paul, Minnesota In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Social Work Committee Members Renee Hepperlen, Ph.D. LICSW Kathryn Evans, MSW, LGSW Jessica Rayle, MSW, LGSW The Clinical Research Project is a graduation requirement for MSW students at St. Catherine University/University of St. -

Need -Adapted - Approach and Open Dialogue in the Integration Timeline

Need -Adapted - Approach and open dialogue in the integration timeline. Ruth Nygård & Sita Rayamajhi Masterarbete / Master’s Thesis Degree Programme in Mental Health 2020 Förnamn Efternamn MASTER’S THESIS Arcada Degree Programme: Master in Mental health Identification number: Author: Ruth Nygård & Sita Rayamajhi Title: Need adapted approach and open dialogue in the integration timeline Supervisor (Arcada): Jukka Piippo Abstract: Introduction Mental health crises in Finland are handled in a special way for example, somatic and psychological symptoms are recommended to be processed as a whole and the client’s situation assessed from various perspectives with the help of different professionals. In the treatment of psychosis the Need-Adapted Approach is recommended as a suitable approach, the evidence-based information is presented by different researchers. The need adapted approach and open dialogue has been proved to be effective in the north-western part of Finland for more than a decade. Aim This study aims to research on how “Need Adapted Approach” (NAA) may benefit the path of integration. Method. The study is based on semi-structured interviews. The data is analyzed using the principle of abductive analysis. Results, Discussion and conclusions In the findings various phases identified in the data analysis process were surprisingly connected to the theory (principles of open dialogue, and what the concept of need adapted approach can mean in the mental challenges during the integration process. (immediate help, social network, flexibility, mobility, responsibility, psychological continuity tolerance of uncertainty and dialogism.) Further detailed findings and limitation of the research in connection with the theory are explained and illustrated by figures provided. -

Five-Year Experience of First-Episode Nonaffective Psychosis in Open

Psychotherapy Research, March 2006; 16(2): 214Á/228 Five-year experience of first-episode nonaffective psychosis in open-dialogue approach: Treatment principles, follow-up outcomes, and two case studies JAAKKO SEIKKULA1, JUKKA AALTONEN1, BIRGITTU ALAKARE2, KAUKO HAARAKANGAS3, JYRKI KERA¨ NEN4, & KLAUS LEHTINEN4 1University of Jyva¨ skyla¨ , 2University of Oulu, 3Western Lapland Health District, 4Western Lapland Health District, and 5Tampere University Hospital (Received 18 January 2004; revised 10 June 2004; accepted 12 July 2004) Abstract The open dialogue (OD) family and network approach aims at treating psychotic patients in their homes. The treatment involves the patient’s social network and starts within 24 hr after contact. Responsibility for the entire treatment process rests with the same team in both inpatient and outpatient settings. The general aim is to generate dialogue with the family to construct words for the experiences that occur when psychotic symptoms exist. In the Finnish Western Lapland a historical comparison of 5-year follow-ups of two groups of first-episode nonaffective psychotic patients were compared, one before (API group; n/ 33) and the other during (ODAP group; n/42) the fully developed phase of using OD approach in all cases. In the ODAP group, the mean duration of untreated psychosis had declined to 3.3 months (p/.069). The ODAP group had both fewer hospital days and fewer family meetings (p B/.001). Nonetheless, no significant differences emerged in the 5-year treatment outcomes. In the ODAP group, 82% did not have any residual psychotic symptoms, 86% had returned to their studies or a full-time job, and 14% were on disability allowance. -

Quadrant M M

q u a $ 20.00 d r a n t X L I I I : 2 S u quadrant m m e Journal of the C. G. Jung Foundation r 2 0 for Analytical Psychology 1 3 XLIII:2 Summer 2013 Maria Taveras Kiley Q. Laughlin Clare Keller Mary Ellen O’Hare-Lavin and Thomas Patrick Lavin The Crowd VIII, 2011, by David Hostetler 28.5’’h x 27’’w Oil on wood panel quadrant Journal of the C.G. Jung Foundation for Analytical Psychology XLIII:2 Summer 2013 quadrant is a publication of the C.G. Jung Foundation for Analytical Psychology of New York Board of Trustees as of January 2013 Karin Barnaby Aisha Holder Anne Ortelee Bruce Bergquist Margaret Maguire Joenine Roberts Karen Bridbord Maxson McDowell David Rottman, President Lesley Crosson Kendrick Norris Jane Selinske Ruth Conner Marie Varley Janet M. Careswell, Executive Director In Association With Archive for Research in NY Association for Archetypal Symbolism Analytical Psychology Sarah Griffin Banker Elizabeth Stevenson C.G. Jung Institute of NY Analytical Psychology Club of NY Laurie Layton Schapira Jane Bloomer Staff For This Issue Webmaster Editor-in-Chief Review Editor Maxson McDowell Kathryn Madden Beth Darlington Art Director/Designer Editorial Assistant Business Managers R. Frank Madden Carol Berlind Janet M. Careswell Arnold DeVera Advertisting Manager Arnold DeVera Editorial Advisory Board Michael Vannoy Adams Tom Kelly Jane Selinske Ann Casement Stanton Marlan Erel Shalit John Dourley Susan Plunket Dennis Patrick Slattery Alexandra Fidyk Robert D. Romanyshyn Ann Belford Ulanov James Hollis Robin van Loben Sels Acknowledgments Our thanks to Ziva Hafner for her invaluable help. -

Open Dialogue: Frequently Asked Questions

University of Southern Denmark Open Dialogue Frequently Asked Questions Ong, Ben; Barbara-May, Rachel; Brown, Judith M.; Dawson, Lisa; Gray, Carl; McCloughen, Andrea; Mikes-Liu, Kristof; Sidis, Anna; Singh, Rajiv; Thorpe, Campbell R.; Buus, Niels Published in: Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy DOI: 10.1002/anzf.1387 Publication date: 2019 Document version: Accepted manuscript Citation for pulished version (APA): Ong, B., Barbara-May, R., Brown, J. M., Dawson, L., Gray, C., McCloughen, A., Mikes-Liu, K., Sidis, A., Singh, R., Thorpe, C. R., & Buus, N. (2019). Open Dialogue: Frequently Asked Questions. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 40(4), 416-428. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1387 Go to publication entry in University of Southern Denmark's Research Portal Terms of use This work is brought to you by the University of Southern Denmark. Unless otherwise specified it has been shared according to the terms for self-archiving. If no other license is stated, these terms apply: • You may download this work for personal use only. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying this open access version If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details and we will investigate your claim. Please direct all enquiries to [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Open Dialogue: Frequently Asked Questions Ben Ong Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District University of Sydney Rachel Barbara-May Headspace, South Eastern Melbourne Youth Early Psychosis Program Alfred Health Child and Youth Mental Health Service, Melbourne Judith M Brown University of NSW Alternate Care Clinic, Redbank, Westmead NSW Lisa Dawson Centre for Family-Based Mental Health Care St. -

Nurses Experiences on Using Open Dialogue Approach in a Local Mental Health Service: an Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis

Nurses experiences on using open dialogue approach in a local mental health service: An interpretative phenomenological analysis Professional Doctorate in Advanced Healthcare Practice Thomas Mark Jones 2019 School of Healthcare Sciences Cardiff University HCARE – Doctor of Advanced Healthcare Practice/ CM20002637 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to all those people who have kept me on the path during this entire course. Thank you to Cardiff and Vale UHB for their ongoing support and backing – I could not have done it without the fantastic teams supporting me. Thanks to Cardiff University for an excellent course – in particular to Dr Jane Harden and to my very dedicated supervisors Dr Nicola Evans and Dr Steve Whitcombe and Dr Michelle Huws-Thomas (I hope this work reflects the amount of support you have given me): along with my research review supervisors. During this course I was fortunate to secure a travel scholarship from the Florence Nightingale Foundation. My travels took me across the world and finally to Finland that allowed me to focus and specify on my chosen topic, which I am very grateful for. Finally, thank you to the ongoing support from my wife Georgina, my son Benjamin and my daughter Menna – I ensured we had plenty of playtime and play days; but sleepless nights for me! cariad mawr xxxx Ac i mam, diolch am bopeth a cariad mawr xxxx Word Count: 69000 I HCARE – Doctor of Advanced Healthcare Practice/ CM20002637 ABSTRACT NURSES EXPERIENCES ON USING OPEN DIALOGUE APPROACH IN A LOCAL MENTAL HEALTH SERVICE: AN INTERPRETATIVE PHENOMENOLOGICAL ANALYSIS Background Open Dialogue Approach (ODA) is a collaborative intervention and framework for using with service users with complex mental health such as psychosis. -

International Two-Year Open Dialogue Training – Seattle, Washington

OPEN DIALOGUE TRAINING TRAINING DETAILS: International Two-Year 8 one-week blocks Monday-Friday Open Dialogue Training – Starts Spring 2022 Seattle, Washington, USA • August 15-19, 2022 Based on the Finnish model of training • October 17-21, 2022 practitioners with supervision, theory, • January 16-20, 2023 practicum, and family-of-origin- • May 1-5, 2023 work seminar days. Advanced family • Summer 2023 (exact date TBD) psychotherapy cohort-based certificate • Fall 2023 (exact date TBD) training with thesis requirement of one’s • Winter 2023-24 (exact date TBD) work. Training will be supervisory/train- • Spring 2024 (exact date TBD) the-trainers level. Two-hundred clinical hours of dialogically-oriented practicum Sessions are 9:00-5:00 PM daily Monday- Friday; 240 hours of face-to-face instruction). work required in-between blocks. Location: Belltown 98121 (TBD) Applications available here: $10,975 (6 payments of $1850 - First www.opendialoguepacific.com payment due 30 days prior to start date) For more information or to request Open Dialogue Pacific newsletter/events email: [email protected] Alita Taylor Alita is a family therapy/psychiatric trainer and supervisor of dialogic practices. She has been a mental health practitioner since 1992. She is a Taos Institute Clinical Associate, An AFTA member, has completed the International Certificate in Collaborative-Dialogic Practices (ICCP) program, and holds a certificate to educate and supervise dialogical practices recognized under Finnish law trained by Jaakko Seikkula, PhD and other Finnish trainers at Dialogic Partners in Espoo, Finland in cooperation with the University of Jyväskylä. She concentrates on co-creating dialogical spaces within organizations and groups.