Tree (Data Structure)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

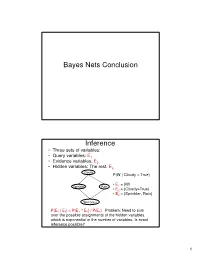

Bayes Nets Conclusion Inference

Bayes Nets Conclusion Inference • Three sets of variables: • Query variables: E1 • Evidence variables: E2 • Hidden variables: The rest, E3 Cloudy P(W | Cloudy = True) • E = {W} Sprinkler Rain 1 • E2 = {Cloudy=True} • E3 = {Sprinkler, Rain} Wet Grass P(E 1 | E 2) = P(E 1 ^ E 2) / P(E 2) Problem: Need to sum over the possible assignments of the hidden variables, which is exponential in the number of variables. Is exact inference possible? 1 A Simple Case A B C D • Suppose that we want to compute P(D = d) from this network. A Simple Case A B C D • Compute P(D = d) by summing the joint probability over all possible values of the remaining variables A, B, and C: P(D === d) === ∑∑∑ P(A === a, B === b,C === c, D === d) a,b,c 2 A Simple Case A B C D • Decompose the joint by using the fact that it is the product of terms of the form: P(X | Parents(X)) P(D === d) === ∑∑∑ P(D === d | C === c)P(C === c | B === b)P(B === b | A === a)P(A === a) a,b,c A Simple Case A B C D • We can avoid computing the sum for all possible triplets ( A,B,C) by distributing the sums inside the product P(D === d) === ∑∑∑ P(D === d | C === c)∑∑∑P(C === c | B === b)∑∑∑P(B === b| A === a)P(A === a) c b a 3 A Simple Case A B C D This term depends only on B and can be written as a 2- valued function fA(b) P(D === d) === ∑∑∑ P(D === d | C === c)∑∑∑P(C === c | B === b)∑∑∑P(B === b| A === a)P(A === a) c b a A Simple Case A B C D This term depends only on c and can be written as a 2- valued function fB(c) === === === === === === P(D d) ∑∑∑ P(D d | C c)∑∑∑P(C c | B b)f A(b) c b …. -

Document Object Model

Document Object Model DOM DOM is a programming interface that provides a way for the values and structure of an XML document to be accessed and manipulated. Tasks that can be performed with DOM . Navigate an XML document's structure, which is a tree stored in memory. Report the information found at the nodes of the XML tree. Add, delete, or modify elements in the XML document. DOM represents each node of the XML tree as an object with properties and behavior for processing the XML. The root of the tree is a Document object. Its children represent the entire XML document except the xml declaration. On the next page we consider a small XML document with comments, a processing instruction, a CDATA section, entity references, and a DOCTYPE declaration, in addition to its element tree. It is valid with respect to a DTD, named root.dtd. <!ELEMENT root (child*)> <!ELEMENT child (name)> <!ELEMENT name (#PCDATA)> <!ATTLIST child position NMTOKEN #REQUIRED> <!ENTITY last1 "Dover"> <!ENTITY last2 "Reckonwith"> Document Object Model Copyright 2005 by Ken Slonneger 1 Example: root.xml <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> <!DOCTYPE root SYSTEM "root.dtd"> <!-- root.xml --> <?DomParse usage="java DomParse root.xml"?> <root> <child position="first"> <name>Eileen &last1;</name> </child> <child position="second"> <name><![CDATA[<<<Amanda>>>]]> &last2;</name> </child> <!-- Could be more children later. --> </root> DOM imagines that this XML information has a document root with four children: 1. A DOCTYPE declaration. 2. A comment. 3. A processing instruction, whose target is DomParse. 4. The root element of the document. The second comment is a child of the root element. -

Balanced Trees Part One

Balanced Trees Part One Balanced Trees ● Balanced search trees are among the most useful and versatile data structures. ● Many programming languages ship with a balanced tree library. ● C++: std::map / std::set ● Java: TreeMap / TreeSet ● Many advanced data structures are layered on top of balanced trees. ● We’ll see several later in the quarter! Where We're Going ● B-Trees (Today) ● A simple type of balanced tree developed for block storage. ● Red/Black Trees (Today/Thursday) ● The canonical balanced binary search tree. ● Augmented Search Trees (Thursday) ● Adding extra information to balanced trees to supercharge the data structure. Outline for Today ● BST Review ● Refresher on basic BST concepts and runtimes. ● Overview of Red/Black Trees ● What we're building toward. ● B-Trees and 2-3-4 Trees ● Simple balanced trees, in depth. ● Intuiting Red/Black Trees ● A much better feel for red/black trees. A Quick BST Review Binary Search Trees ● A binary search tree is a binary tree with 9 the following properties: 5 13 ● Each node in the BST stores a key, and 1 6 10 14 optionally, some auxiliary information. 3 7 11 15 ● The key of every node in a BST is strictly greater than all keys 2 4 8 12 to its left and strictly smaller than all keys to its right. Binary Search Trees ● The height of a binary search tree is the 9 length of the longest path from the root to a 5 13 leaf, measured in the number of edges. 1 6 10 14 ● A tree with one node has height 0. -

Trees: Binary Search Trees

COMP2012H Spring 2014 Dekai Wu Binary Trees & Binary Search Trees (data structures for the dictionary ADT) Outline } Binary tree terminology } Tree traversals: preorder, inorder and postorder } Dictionary and binary search tree } Binary search tree operations } Search } min and max } Successor } Insertion } Deletion } Tree balancing issue COMP2012H (BST) Binary Tree Terminology } Go to the supplementary notes COMP2012H (BST) Linked Representation of Binary Trees } The degree of a node is the number of children it has. The degree of a tree is the maximum of its element degree. } In a binary tree, the tree degree is two data } Each node has two links left right } one to the left child of the node } one to the right child of the node Left child Right child } if no child node exists for a node, the link is set to NULL root 32 32 79 42 79 42 / 13 95 16 13 95 16 / / / / / / COMP2012H (BST) Binary Trees as Recursive Data Structures } A binary tree is either empty … Anchor or } Consists of a node called the root } Root points to two disjoint binary (sub)trees Inductive step left and right (sub)tree r left right subtree subtree COMP2012H (BST) Tree Traversal is Also Recursive (Preorder example) If the binary tree is empty then Anchor do nothing Else N: Visit the root, process data L: Traverse the left subtree Inductive/Recursive step R: Traverse the right subtree COMP2012H (BST) 3 Types of Tree Traversal } If the pointer to the node is not NULL: } Preorder: Node, Left subtree, Right subtree } Inorder: Left subtree, Node, Right subtree Inductive/Recursive step } Postorder: Left subtree, Right subtree, Node template <class T> void BinaryTree<T>::InOrder( void(*Visit)(BinaryTreeNode<T> *u), template<class T> BinaryTreeNode<T> *t) void BinaryTree<T>::PreOrder( {// Inorder traversal. -

Q-Tree: a Multi-Attribute Based Range Query Solution for Tele-Immersive Framework

Q-Tree: A Multi-Attribute Based Range Query Solution for Tele-Immersive Framework Md Ahsan Arefin, Md Yusuf Sarwar Uddin, Indranil Gupta, Klara Nahrstedt Department of Computer Science University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign Illinois, USA {marefin2, mduddin2, indy, klara}@illinois.edu Abstract given in a high level description which are transformed into multi-attribute composite range queries. Some of the Users and administrators of large distributed systems are examples include “which site is highly congested?”, “which frequently in need of monitoring and management of its components are not working properly?” etc. To answer the various components, data items and resources. Though there first one, the query is transformed into a multi-attribute exist several distributed query and aggregation systems, the composite range query with constrains (range of values) on clustered structure of tele-immersive interactive frameworks CPU utilization, memory overhead, stream rate, bandwidth and their time-sensitive nature and application requirements utilization, delay and packet loss rate. The later one can represent a new class of systems which poses different chal- be answered by constructing a multi-attribute range query lenges on this distributed search. Multi-attribute composite with constrains on static and dynamic characteristics of range queries are one of the key features in this class. those components. Queries can also be made by defining Queries are given in high level descriptions and then trans- different multi-attribute ranges explicitly. Another mention- formed into multi-attribute composite range queries. Design- able property of such systems is that the number of site is ing such a query engine with minimum traffic overhead, low limited due to limited display space and limited interactions, service latency, and with static and dynamic nature of large but the number of data items to store and manage can datasets, is a challenging task. -

NICOLAS WU Department of Computer Science, University of Bristol (E-Mail: [email protected], [email protected])

Hinze, R., & Wu, N. (2016). Unifying Structured Recursion Schemes. Journal of Functional Programming, 26, [e1]. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0956796815000258 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1017/S0956796815000258 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ ZU064-05-FPR URS 15 September 2015 9:20 Under consideration for publication in J. Functional Programming 1 Unifying Structured Recursion Schemes An Extended Study RALF HINZE Department of Computer Science, University of Oxford NICOLAS WU Department of Computer Science, University of Bristol (e-mail: [email protected], [email protected]) Abstract Folds and unfolds have been understood as fundamental building blocks for total programming, and have been extended to form an entire zoo of specialised structured recursion schemes. A great number of these schemes were unified by the introduction of adjoint folds, but more exotic beasts such as recursion schemes from comonads proved to be elusive. In this paper, we show how the two canonical derivations of adjunctions from (co)monads yield recursion schemes of significant computational importance: monadic catamorphisms come from the Kleisli construction, and more astonishingly, the elusive recursion schemes from comonads come from the Eilenberg-Moore construction. Thus we demonstrate that adjoint folds are more unifying than previously believed. 1 Introduction Functional programmers have long realised that the full expressive power of recursion is untamable, and so intensive research has been carried out into the identification of an entire zoo of structured recursion schemes that are well-behaved and more amenable to program comprehension and analysis (Meijer et al., 1991). -

Exploring and Extracting Nodes from Large XML Files

Exploring and Extracting Nodes from Large XML Files Guy Lapalme January 2010 Abstract This article shows how to deal simply with large XML files that cannot be read as a whole in memory and for which the usual XML exploration and extraction mechanisms cannot work or are very inefficient in processing time. We define the notion of a skeleton document that is maintained as the file is read using a pull- parser. It is used for showing the structure of the document and for selecting parts of it. 1 Introduction XML has been developed to facilitate the annotation of information to be shared between computer systems. Because it is intended to be easily generated and parsed by computer systems on all platforms, its format is based on character streams rather than internal binary ones. Being character-based, it also has the nice property of being readable and editable by humans using standard text editors. XML is based on a uniform, simple and yet powerful model of data organization: the generalized tree. Such a tree is defined as either a single element or an element having other trees as its sub-elements called children. This is the same model as the one chosen for the Lisp programming language 50 years ago. This hierarchical model is very simple and allows a simple annotation of the data. The left part of Figure 1 shows a very small XML file illustrating the basic notation: an arbitrary name between < and > symbols is given to a node of a tree. This is called a start-tag. -

Tree Structures

Tree Structures Definitions: o A tree is a connected acyclic graph. o A disconnected acyclic graph is called a forest o A tree is a connected digraph with these properties: . There is exactly one node (Root) with in-degree=0 . All other nodes have in-degree=1 . A leaf is a node with out-degree=0 . There is exactly one path from the root to any leaf o The degree of a tree is the maximum out-degree of the nodes in the tree. o If (X,Y) is a path: X is an ancestor of Y, and Y is a descendant of X. Root X Y CSci 1112 – Algorithms and Data Structures, A. Bellaachia Page 1 Level of a node: Level 0 or 1 1 or 2 2 or 3 3 or 4 Height or depth: o The depth of a node is the number of edges from the root to the node. o The root node has depth zero o The height of a node is the number of edges from the node to the deepest leaf. o The height of a tree is a height of the root. o The height of the root is the height of the tree o Leaf nodes have height zero o A tree with only a single node (hence both a root and leaf) has depth and height zero. o An empty tree (tree with no nodes) has depth and height −1. o It is the maximum level of any node in the tree. CSci 1112 – Algorithms and Data Structures, A. -

A Simple Linear-Time Algorithm for Finding Path-Decompostions of Small Width

Introduction Preliminary Definitions Pathwidth Algorithm Summary A Simple Linear-Time Algorithm for Finding Path-Decompostions of Small Width Kevin Cattell Michael J. Dinneen Michael R. Fellows Department of Computer Science University of Victoria Victoria, B.C. Canada V8W 3P6 Information Processing Letters 57 (1996) 197–203 Kevin Cattell, Michael J. Dinneen, Michael R. Fellows Linear-Time Path-Decomposition Algorithm Introduction Preliminary Definitions Pathwidth Algorithm Summary Outline 1 Introduction Motivation History 2 Preliminary Definitions Boundaried graphs Path-decompositions Topological tree obstructions 3 Pathwidth Algorithm Main result Linear-time algorithm Proof of correctness Other results Kevin Cattell, Michael J. Dinneen, Michael R. Fellows Linear-Time Path-Decomposition Algorithm Introduction Preliminary Definitions Motivation Pathwidth Algorithm History Summary Motivation Pathwidth is related to several VLSI layout problems: vertex separation link gate matrix layout edge search number ... Usefullness of bounded treewidth in: study of graph minors (Robertson and Seymour) input restrictions for many NP-complete problems (fixed-parameter complexity) Kevin Cattell, Michael J. Dinneen, Michael R. Fellows Linear-Time Path-Decomposition Algorithm Introduction Preliminary Definitions Motivation Pathwidth Algorithm History Summary History General problem(s) is NP-complete Input: Graph G, integer t Question: Is tree/path-width(G) ≤ t? Algorithmic development (fixed t): O(n2) nonconstructive treewidth algorithm by Robertson and Seymour (1986) O(nt+2) treewidth algorithm due to Arnberg, Corneil and Proskurowski (1987) O(n log n) treewidth algorithm due to Reed (1992) 2 O(2t n) treewidth algorithm due to Bodlaender (1993) O(n log2 n) pathwidth algorithm due to Ellis, Sudborough and Turner (1994) Kevin Cattell, Michael J. Dinneen, Michael R. -

AVL Trees, Page 1 ' $

CS 310 AVL Trees, Page 1 ' $ Motives of Balanced Trees Worst-case search steps #ofentries complete binary tree skewed binary tree 15 4 15 63 6 63 1023 10 1023 65535 16 65535 1,048,575 20 1048575 1,073,741,823 30 1073741823 & % CS 310 AVL Trees, Page 2 ' $ Analysis r • logx y =anumberr such that x = y ☞ log2 1024 = 10 ☞ log2 65536 = 16 ☞ log2 1048576 = 20 ☞ log2 1073741824 = 30 •bxc = an integer a such that a ≤ x dxe = an integer a such that a ≥ x ☞ b3.1416c =3 ☞ d3.1416e =4 ☞ b5c =5=d5e & % CS 310 AVL Trees, Page 3 ' $ • If a binary search tree of N nodes happens to be complete, then a search in the tree requires at most b c log2 N +1 steps. • Big-O notation: We say f(x)=O(g(x)) if f(x)isbounded by c · g(x), where c is a constant, for sufficiently large x. ☞ x2 +11x − 30 = O(x2) (consider c =2,x ≥ 6) ☞ x100 + x50 +2x = O(2x) • If a BST happens to be complete, then a search in the tree requires O(log2 N)steps. • In a linked list of N nodes, a search requires O(N)steps. & % CS 310 AVL Trees, Page 4 ' $ AVL Trees • A balanced binary search tree structure proposed by Adelson, Velksii and Landis in 1962. • In an AVL tree of N nodes, every searching, deletion or insertion operation requires only O(log2 N)steps. • AVL tree searching is exactly the same as that of the binary search tree. & % CS 310 AVL Trees, Page 5 ' $ Definition • An empty tree is balanced. -

Chapter 10 Document Object Model and Dynamic HTML

Chapter 10 Document Object Model and Dynamic HTML The term Dynamic HTML, often abbreviated as DHTML, refers to the technique of making Web pages dynamic by client-side scripting to manipulate the document content and presen- tation. Web pages can be made more lively, dynamic, or interactive by DHTML techniques. With DHTML you can prescribe actions triggered by browser events to make the page more lively and responsive. Such actions may alter the content and appearance of any parts of the page. The changes are fast and e±cient because they are made by the browser without having to network with any servers. Typically the client-side scripting is written in Javascript which is being standardized. Chapter 9 already introduced Javascript and basic techniques for making Web pages dynamic. Contrary to what the name may suggest, DHTML is not a markup language or a software tool. It is a technique to make dynamic Web pages via client-side programming. In the past, DHTML relies on browser/vendor speci¯c features to work. Making such pages work for all browsers requires much e®ort, testing, and unnecessarily long programs. Standardization e®orts at W3C and elsewhere are making it possible to write standard- based DHTML that work for all compliant browsers. Standard-based DHTML involves three aspects: 447 448 CHAPTER 10. DOCUMENT OBJECT MODEL AND DYNAMIC HTML Figure 10.1: DOM Compliant Browser Browser Javascript DOM API XHTML Document 1. Javascript|for cross-browser scripting (Chapter 9) 2. Cascading Style Sheets (CSS)|for style and presentation control (Chapter 6) 3. Document Object Model (DOM)|for a uniform programming interface to access and manipulate the Web page as a document When these three aspects are combined, you get the ability to program changes in Web pages in reaction to user or browser generated events, and therefore to make HTML pages more dynamic. -

Ch08-Dom.Pdf

Web Programming Step by Step Chapter 8 The Document Object Model (DOM) Except where otherwise noted, the contents of this presentation are Copyright 2009 Marty Stepp and Jessica Miller. 8.1: Global DOM Objects 8.1: Global DOM Objects 8.2: DOM Element Objects 8.3: The DOM Tree The six global DOM objects Every Javascript program can refer to the following global objects: name description document current HTML page and its content history list of pages the user has visited location URL of the current HTML page navigator info about the web browser you are using screen info about the screen area occupied by the browser window the browser window The window object the entire browser window; the top-level object in DOM hierarchy technically, all global code and variables become part of the window object properties: document , history , location , name methods: alert , confirm , prompt (popup boxes) setInterval , setTimeout clearInterval , clearTimeout (timers) open , close (popping up new browser windows) blur , focus , moveBy , moveTo , print , resizeBy , resizeTo , scrollBy , scrollTo The document object the current web page and the elements inside it properties: anchors , body , cookie , domain , forms , images , links , referrer , title , URL methods: getElementById getElementsByName getElementsByTagName close , open , write , writeln complete list The location object the URL of the current web page properties: host , hostname , href , pathname , port , protocol , search methods: assign , reload , replace complete list The navigator object information about the web browser application properties: appName , appVersion , browserLanguage , cookieEnabled , platform , userAgent complete list Some web programmers examine the navigator object to see what browser is being used, and write browser-specific scripts and hacks: if (navigator.appName === "Microsoft Internet Explorer") { ..