Wilhelm PETERSON-BERGER (1867-1942) Symphony No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

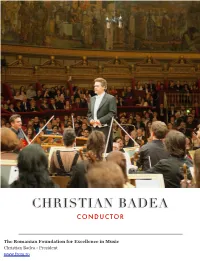

Christian Badea Conductor

CHRISTIAN BADEA CONDUCTOR The Romanian Foundation for Excellence in Music Christian Badea - President www.frem.ro Christian Badea has received exceptional acclaim throughout his career, which encompasses prestigious engagements in the foremost concert halls and opera houses of Europe, North America, Asia and Australia. Equally dividing his time between symphony and opera conducting, Christian Badea has appeared as a frequent guest in the major opera houses of the world. At the Metropolitan Opera in New York he conducted 167 performances in a wide variety of repertoire, including many of the MET international broadcasts. Among the opera houses where Christian Badea has guest conducted, are the Vienna State Opera, the Royal Opera House of Covent Garden in London, the Bayerische Staatsoper in München, the Staatsoper in Hamburg, the Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf, the Grand Théâtre de Genève, the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels, the Netherlands Opera in Amsterdam, the Royal Opera theaters in Copenhagen and Stockholm, the Oslo Opera, the Teatro Regio in Torino and the Teatro 1 Christian Badea at the Metropolitan Opera - New York Comunale in Bologna, the Opera National de Lyon and in North America - the opera companies of Houston, Dallas, Toronto, Montreal and Detroit. In recent years, Christian Badea has received great acclaim for his work at the Budapest State Opera (Tannhäuser, Der fliegende Holländer and Parsifal) , the Sydney Opera with new productions of Tosca, La bohème, Die tote Stadt, Otello and Falstaff, Oslo Opera – a new production of Tannhäuser, collaborating with stage director Stefan Herheim and Goteborg Opera – a new Don Carlo and Turandot. -

In Santa Cruz This Summer for Special Summer Encore Productions

Contact: Peter Koht (831) 420-5154 [email protected] Release Date: Immediate “THE MET: LIVE IN HD” IN SANTA CRUZ THIS SUMMER FOR SPECIAL SUMMER ENCORE PRODUCTIONS New York and Centennial, Colo. – July 1, 2010 – The Metropolitan Opera and NCM Fathom present a series of four encore performances from the historic archives of the Peabody Award- winning The Met: Live in HD series in select movie theaters nationwide, including the Cinema 9 in Downtown Santa Cruz. Since 2006, NCM Fathom and The Metropolitan Opera have partnered to bring classic operatic performances to movie screens across America live with The Met: Live in HD series. The first Live in HD event was seen in 56 theaters in December 2006. Fathom has since expanded its participating theater footprint which now reaches more than 500 movie theaters in the United States. We’re thrilled to see these world class performances offered right here in downtown Santa Cruz,” said councilmember Cynthia Mathews. “We know there’s a dedicated base of local opera fans and a strong regional audience for these broadcasts. Now, thanks to contemporary technology and a creative partnership, the Metropolitan Opera performances will become a valuable addition to our already stellar lineup of visual and performing arts.” Tickets for The Met: Live in HD 2010 Summer Encores, shown in theaters on Wednesday evenings at 6:30 p.m. in all time zones and select Thursday matinees, are available at www.FathomEvents.com or by visiting the Regal Cinema’s box office. This summer’s series will feature: . Eugene Onegin – Wednesday, July 7 and Thursday, July 8– Soprano Renée Fleming and baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky star in Tchaikovsky’s lushly romantic masterpiece about mistimed love. -

8D09d17db6e0f577e57756d021

rus «Как дуб вырастает из желудя, так и вся русская симфоническая музыка повела свое начало из “Камаринской” Глинки», – писал П.И. Чайковский. Основоположник русской национальной композиторской школы Михаил Иванович Глинка с детства любил оркестр и предпочитал сим- фоническую музыку всякой другой (оркестром из крепостных музы- кантов владел дядя будущего композитора, живший неподалеку от его родового имения Новоспасское). Первые пробы пера в оркестро- вой музыке относятся к первой половине 1820-х гг.; уже в них юный композитор уходит от инструментального озвучивания популярных песен и танцев в духе «бальной музыки» того времени, но ориентируясь на образцы высокого классицизма, стремится освоить форму увертюры и симфонии с использованием народно-песенного материала. Эти опыты, многие из которых остались незаконченными, были для Глинки лишь учебными «эскизами», но они сыграли важную роль в формирова- нии его композиторского стиля. 7 rus rus Уже в увертюрах и балетных фрагментах опер «Жизнь за царя» (1836) Александр Сергеевич Даргомыжский был младшим современником и «Руслан и Людмила» (1842) Глинка демонстрирует блестящее вла- и последователем Глинки в деле становления и развития русской про- дение оркестровым письмом. Особенно характерна в этом отноше- фессиональной музыкальной культуры. На репетициях «Жизни за царя» нии увертюра к «Руслану»: поистине моцартовская динамичность, он познакомился с автором оперы; сам Глинка, отметив выдающиеся «солнечный» жизнерадостный тонус (по словам автора, она «летит музыкальные способности юноши, передал ему свои тетради музыкаль- на всех парусах») сочетается в ней с интенсивнейшим мотивно- ных упражнений, над которыми работал вместе с немецким теоретиком тематическим развитием. Как и «Восточные танцы» из IV действия, Зигфридом Деном. Даргомыжский известен, прежде всего, как оперный она превратилась в яркий концертный номер. Но к подлинному сим- и вокальный композитор; между тем оркестровое творчество по-своему фоническому творчеству Глинка обратился лишь в последнее десяти- отражает его композиторскую индивидуальность. -

Musiker-Lexikon Des Herzogtums Sachsen-Meiningen (1680-1918)

Maren Goltz Musiker-Lexikon des Herzogtums Sachsen-Meiningen (1680 - 1918) Meiningen 2012 Impressum urn:nbn:de:gbv:547-201200041 Titelbild Karl Piening mit Fritz Steinbach und Carl Wendling vor dem Meininger Theater, Photographie, undatiert, Meininger Museen B 617 2 Vorwort Das Herzogtum Sachsen-Meiningen (1680–1918) besitzt in kultureller Hinsicht eine Sonderstellung. Persönlichkeiten wie Hans von Bülow, Johannes Brahms, Richard Strauss, Fritz Steinbach und Max Reger verankerten es in der europäischen Musikgeschichte und verhalfen ihm zu einem exzellenten Ruf unter Musikern, Musikinteressierten und Gelehrten. Doch die Musikgeschichte dieser Region lässt sich nicht allein auf das Werk einzelner Lichtgestalten reduzieren. Zu bedeutsam und nachhaltig sind die komplexen Verflechtungen, welche die als überlieferungswürdig angesehenen Höchstleistungen erst ermöglichten. Trotz der Bedeutung des Herzogtums für die europäische Musikgeschichte und einer erstaunlichen Quellendichte standen bislang immer nur bestimmte Aspekte im Blickpunkt der Forschung. Einzelne Musiker bzw. Ensembles oder zeitliche bzw. regionale Fragestellungen beleuchten die Monographien „Die Herzogliche Hofkapelle in Meiningen“ (Mühlfeld, Meiningen 1910), „Hildburghäuser Musiker“ (Ullrich, Hildburghausen 2003), „Musiker und Monarchen in Meiningen 1680–1763“ (Erck/Schneider, Meiningen 2006) oder „Der Brahms- Klarinettist Richard Mühlfeld“ (Goltz/Müller, Balve 2007). Mit dem vorliegenden „Musiker-Lexikon des Herzogtums Sachsen-Meiningen“ wird erstmals der Versuch unternommen, -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

October 17, 2018: (Full-Page Version) Close Window “The Only Love Affair I Have Ever Had Was with Music.” —Maurice Ravel

October 17, 2018: (Full-page version) Close Window “The only love affair I have ever had was with music.” —Maurice Ravel Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Fernandez/English Chamber 00:01 Buy Now! Vivaldi Lute Concerto in D, RV 93 London 289 455 364 028945536422 Awake! Orchestra/Malcolm 00:13 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. 059 in A, "Fire" English Concert/Pinnock Archiv 427 661 028942766129 00:32 Buy Now! Fauré Violin Sonata No. 1 in A, Op. 13 Mintz/Bronfman DG 423 065 028942306523 01:01 Buy Now! Suppe Overture ~ Poet and Peasant Philharmonia/Boughton Nimbus 5120 083603512026 01:11 Buy Now! Gabrieli, D. Ricercar II in A minor Anner Bylsma DHM 7978 054727797828 01:22 Buy Now! Howells Rhapsody in D flat, Op. 17 No. 1 Christopher Jacobson Pentatone 5186 577 827949057762 Hoffmann, German Chamber Academy of 01:28 Buy Now! Harlequin Ballet cpo 999 606 761203960620 E.T.A. Neuss/Goritzki 02:01 Buy Now! Brahms Cello Sonata No. 2 in F, Op. 99 Harrell/Kovacevich EMI 56440 724355644022 02:29 Buy Now! Bach Prelude in E flat, BWV 552 Läubin Brass Ensemble DG 423 988 028942398825 Rimsky- 02:39 Buy Now! Suite ~ The Tale of Tsar Saltan, Op. 57 Suisse Romande Orchestra/Ansermet London 443 464 02894434642 Korsakov 02:59 Buy Now! Chopin Polonaise in A flat, Op. 53 "Heroic" Biret Naxos www.theclassicalstation.org n/a 03:08 Buy Now! Dvorak Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70 Vienna Philharmonic/Kubelik Decca 289 466 994 028946699423 03:45 Buy Now! Strauss, R. -

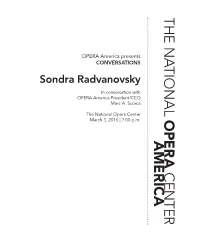

Th E N a Tion a Lo Pe R a C En Ter Am Er Ic A

THE NATIONA OPERA America presents CONVERSATIONS Sondra Radvanovsky In conversation with OPERA America President/CEO Marc A. Scorca L The National Opera Center March 3, 2016 | 7:00 p.m. OPERA AM ER CENTER ICA Soprano SONDRA Radvanovsky has performed in every RADVANOVSKY is a major opera house in the world, PAVEL ANTONOV PAVEL globally celebrated including the Royal Opera House, artist. The sincerity and Opéra national de Paris, Teatro alla intensity that she brings Scala and numerous others. Her home to the stage as one of theater is the Metropolitan Opera, the most prominent where she began her training in the late sopranos of her generation have won 1990s. After performances in smaller her accolades from critics and loyalty roles there, Radvanovsky caught the from passionate fans. attention of critics as Antonia in Les Contes d’Hoffmann and was singled out Though known as one of today’s as a soprano to watch. Her recordings premier Verdi sopranos, Radvanovsky include Verdi Arias and a CD of Verdi has recently expanded her repertoire opera scenes with her frequent artistic to include such bel canto roles as partner Dmitri Hvorostovsky. She also Norma and Donizetti’s “three queens,” stars in a Naxos DVD of Cyrano de the leading soprano parts in his Bergerac alongside Plácido Domingo Tudor dramas. In recent seasons, she and in transmissions of Il trovatore and has mastered the title roles in Anna Un ballo in maschera for the wildly Bolena and Maria Stuarda and the popular Met: Live in HD series. role of Queen Elizabeth in Roberto Devereux, and this season, in a feat never before undertaken by any singer in Metropolitan Opera history, Radvanovsky performs all three queens in a single season. -

07 – Spinning the Record

VI. THE STEREO ERA In 1954, a timid and uncertain record industry took the plunge to begin investing heav- ily in stereophonic sound. They were not timid and uncertain because they didn’t know if their system would work – as we have seen, they had already been experimenting with and working the kinks out of stereo sound since 1932 – but because they still weren’t sure how to make a home entertainment system that could play a stereo record. Nevertheless, they all had their various equipment in place, and so that year they began tentatively to make recordings using the new medium. RCA started, gingerly, with “alternate” stereo tapes of monophonic recording sessions. Unfortunately, since they were still uncertain how the results would sound on home audio, they often didn’t mark and/or didn’t file the alternate stereo takes properly. As a result, the stereo versions of Charles Munch’s first stereo recordings – Berlioz’ “Roméo et Juliette” and “Symphonie Fanastique” – disappeared while others, such as Fritz Reiner’s first stereo re- cordings (Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra” and the Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1 with Ar- thur Rubinstein) disappeared for 20 years. Oddly enough, their prize possession, Toscanini, was not recorded in stereo until his very last NBC Symphony performance, at which he suf- fered a mental lapse while conducting. None of the performances captured on that date were even worth preserving, let alone issuing, and so posterity lost an opportunity to hear his last half-season with NBC in the excellent sound his artistry deserved. Columbia was even less willing to pursue stereo. -

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan a Dissertation Submitted

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: David Alexander Rahbee, Chair JoAnn Taricani Timothy Salzman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2016 Tigran Arakelyan University of Washington Abstract Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. David Alexander Rahbee School of Music The goal of this dissertation is to make available all relevant information about orchestral music by Armenian composers—including composers of Armenian descent—as well as the history pertaining to these composers and their works. This dissertation will serve as a unifying element in bringing the Armenians in the diaspora and in the homeland together through the power of music. The information collected for each piece includes instrumentation, duration, publisher information, and other details. This research will be beneficial for music students, conductors, orchestra managers, festival organizers, cultural event planning and those studying the influences of Armenian folk music in orchestral writing. It is especially intended to be useful in searching for music by Armenian composers for thematic and cultural programing, as it should aid in the acquisition of parts from publishers. In the early part of the 20th century, Armenian people were oppressed by the Ottoman government and a mass genocide against Armenians occurred. Many Armenians fled -

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>V VIENNA, Austria, Germany, Hungary, etc. The Vienna Philharmonic was the jewel in Decca’s crown, particularly from 1956 when the engineers adopted the Sofiensaal as their favoured studio. The contract with the orchestra was secured partly by cultivating various chamber ensembles drawn from its membership. Vienna was favoured for symphonic cycles, particularly in the mid-1960s, and for German opera and operetta, including Strausses of all varieties and Solti’s “Ring” (1958-65), as well as Mackerras’s Janá ček (1976-82). Karajan recorded intermittently for Decca with the VPO from 1959-78. But apart from the New Year concerts, resumed in 2008, recording with the VPO ceased in 1998. Outside the capital there were various sessions in Salzburg from 1984-99. Germany was largely left to Decca’s partner Telefunken, though it was so overshadowed by Deutsche Grammophon and EMI Electrola that few of its products were marketed in the UK, with even those soon relegated to a cheap label. It later signed Harnoncourt and eventually became part of the competition, joining Warner Classics in 1990. Decca did venture to Bayreuth in 1951, ’53 and ’55 but wrecking tactics by Walter Legge blocked the release of several recordings for half a century. The Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra’s sessions moved from Geneva to its home town in 1963 and continued there until 1985. The exiled Philharmonia Hungarica recorded in West Germany from 1969-75. There were a few engagements with the Bavarian Radio in Munich from 1977- 82, but the first substantial contract with a German symphony orchestra did not come until 1982. -

Read the LIVE 2018 Disc 8 Notes

MILY BALAKIREV (1837–1910) Octet for Winds, Strings, and Piano, op. 3 (1855–1856) As a child, Mily Balakirev demonstrated promising musical Creative Capitals 2018: Liner notes, disc 8. aptitude and enjoyed the support of Aleksandr Ulïbïshev [pro- nounced Uluh- BYSHev], the most prominent musical figure The sixteenth edition of Music@Menlo LIVE visits seven of and patron in his native city of Nizhny Novgorod. Ulïbïshev, Western music’s most flourishing Creative Capitals—London, the author of books on Mozart and Beethoven, introduced the Paris, St. Petersburg, Leipzig, Berlin, Budapest, and Vienna. young Balakirev to music by those composers as well as by Cho- Each disc explores the music that has emanated from these cul- pin and Mikhail Glinka. In 1855, Balakirev traveled to St. Peters- tural epicenters, comprising an astonishingly diverse repertoire burg, where Ulïbïshev introduced him to Glinka himself. Glinka spanning some three hundred years that together largely forms became a consequential mentor to the eighteen-year-old pianist the canon of Western music. Many of history’s greatest com- and composer. That year also saw numerous important con- posers have helped to define the spirit of these flagship cities cert appearances for Balakirev. In February, he performed in St. through their music, and in this edition of recordings, Music@ Petersburg as the soloist in the first movement of a projected Menlo celebrates the many artistic triumphs that have emerged piano concerto; later that spring, also in St. Petersburg, he gave from the fertile ground of these Creative Capitals. a concert of his own solo piano and chamber compositions.