Manafort Plea Reminds Us of Whitewater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of the Mueller Report on the Public Opinion of the 45Th President of the US

The Impact of the Mueller Report on the Public Opinion of the 45th President of the US Andrey Reznikov Black Hills State University After 22 months-long investigation, special Counsel Robert Mueller submitted his report to US Attorney General on March 22, 2019. The report consists of two volumes: volume I deals with the Russian interference in 2016 elections; volume II documents obstruction of justice incidents. Mueller’s team filed charges against 37 individuals, obtained 7 guilty pleas, and 1 conviction at trial. One of the most important conclusions, repeated throughout the report, is the following statement: If we had confidence after a thorough investigation of the facts that the president clearly did not commit obstruction of justice, we would so state. Based on the facts and the applicable legal standards, we are unable to reach that conclusion. Accordingly, while this report does not conclude that the President committed a crime, it also does not exonerate him. (Mueller 329-330, vol. II) Such a conclusion alone, even without the knowledge of the facts listed in the report, should have had a substantial impact on the public opinion of the President. However, the public mostly remained quite indifferent. Thus, the question we need to answer is – why? Why the impact of the arguably most important legal document of our time was so miserable? The short answer is simple and obvious: because no one (except pundits) has read the report. That answer begs another question – why the document which was so impatiently anticipated remained mostly unread by the American public? If you ask several people in the street if they will read a 400-page text, they will say they do not have time for that. -

Vol IV Part F Ch. 1 DOJ Handling of the RTC Referrals

PART F THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE'S HANDLING OF THE RTC CRIMINAL REFERRALS AND THE CONTACTS BETWEEN THE WHITE HOUSE AND THE DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Chapter 1: DOJ Handling of the RTC Referrals I. INTRODUCTION The potential involvement of President Clinton with matters in criminal referral C-0004 raised questions about the proper handling of the referral by the Department of Justice. The referral identified him and Mrs. Clinton as potential witnesses to the alleged criminal conduct relating to Madison Guaranty by Jim McDougal. The delay in full consideration of the referral between September 1992 and the ultimate appointment of a regulatory independent counsel in January 1994 required investigation of whether any action during that time was intended to prevent full examination of the conduct alleged in the referral. Whether before or after the 1992 election of President Clinton, any action that had the effect of delaying or impeding the investigation could raise the question of whether anyone in the Department of Justice unlawfully obstructed the investigation in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1505. This investigation examined the conduct and motives of Department of Justice officials in a position to influence the handling of the referral. These officials included President Bush's U.S. Attorney in Little Rock, President Clinton's subsequent appointee as the U.S. Attorney, and officials at the Department of Justice headquarters in Washington D.C. both at the end of the Bush Administration and during the first year of the Clinton Administration. II. FINDINGS The Independent Counsel concluded the evidence was insufficient to prove that any Department of Justice official obstructed justice by engaging in conduct intended to delay or impede the investigation of the RTC's criminal referral C-0004. -

Part C Webster L. Hubbell's Billing Practices and Tax Filings

PART C WEBSTER L. HUBBELL'S BILLING PRACTICES AND TAX FILINGS I. INTRODUCTION Shortly after their former partner Webster L. Hubbell became Associate Attorney General of the United States in January 1993, Rose Law Firm members in Little Rock found irregularities in Hubbell's billings for 1989-92. In March 1994, regulatory Independent Counsel Robert Fiske, received information that Hubbell may have violated federal criminal laws through his billing activities. Mr. Fiske then opened a criminal investigation. In the wake of these inquiries, Hubbell announced his resignation as the Associate Attorney General on March 14, 1994, saying this would allow him to settle the matter. Upon his appointment in August 1994, Independent Counsel Starr continued the investigation already started by Mr. Fiske. This resulted in Hubbell pleading guilty to one felony count of mail fraud and one felony count of tax evasion in December 1994, admitting that he defrauded his former partners and clients out of at least $394,000.1 On June 28, 1995, Judge George Howard sentenced Hubbell to twenty-one months' imprisonment.2 Sometime after Hubbell's sentencing, the Independent Counsel learned that a meeting had been held at the White House the day before Hubbell announced his resignation, where Hubbell's problems and resignation were discussed. Senior White House officials, including the President, 1 Plea Agreement, United States v. Webster Lee Hubbell, No. 94-241 (E.D. Ark. Dec. 6, 1994). Hubbell's attorney later agreed that Hubbell "obtained $482,410.83 by fraudulent means from the Rose Law Firm and its clients." Pre-sentence Investigation Report (Final Draft), United States v. -

Robert Mueller Testimony

Colborn, Paul P (OLC) From: Colborn, Paul P (OLC) Sent: Tuesday, May 14, 2019 9:54 AM To: Engel, Steven A. (OLC); Gannon, Curtis E. (OLC) Subject: Fwd: Discuss Mueller testimony Won't be back until 12:15 or later. Could join noon meeting late and can do 3:30. Sent from my iPhone Begin forwarded message: From: "Lasseter, David F. {OLA)" <[email protected]> Date: May 14, 2019 at 9:51:28 AM EDT To: "O'Callaghan, Edward C. (OOAG}" <[email protected]>, "Rabbitt, Brian (OAG)" <[email protected]>, "Weinsheimer, Bradley (ODAG)" <[email protected]>, "Engel, Steven A. (OLC)" ,., (b) (6) per OLC , "Colborn, Paul P (OLC)" ,., (b) (6) per OLC >, "Gannon, Curtis E. (OLC)" > Cc: "Boyd, Stephen E. (OLA)" <[email protected]> Subject: Discuss Mueller testimony Good morning all. Could we gather today to discuss the potential testimony of Mr. Mueller (b) (5) I SCO is discussing the scheduling of the testimony with HJC and HPSCI but needs to be better informed on the process as they seek an agreement. Would noon or 3:30 work? Thanks, David David F. Lasseter Document ID: 0.7.23922.34583 Rabbitt, Brian (OAG) From: Rabbitt, Brian (OAG) Sent: Tuesday, May 14, 2019 10:27 AM To: Engel, Steven A. (O LC); Lasseter, David F. {OLA); O'Callaghan, Edward C. (OOAG); Weinsheimer, Bradley (OOAG); Colborn, Paul P (OLC); Gannon, Curtis E. {O LC) Cc: Boyd, Stephen E. {OLA) Subject: RE: Discuss Mueller testimony 330 would be best for me. -Original Message---- From: Engel, Steven A. (OLC) < (b) (6) per OLC •> Sent: Tuesday, May 14, 2019 10:04 AM To: Lasseter, David F. -

Questioning the National Security Agency's Metadata Program

I/S: A JOURNAL OF LAW AND POLICY FOR THE INFORMATION SOCIETY Secret without Reason and Costly without Accomplishment: Questioning the National Security Agency’s Metadata Program JOHN MUELLER & MARK G. STEWART* I. INTRODUCTION When Edward Snowden’s revelations emerged in June 2013 about the extent to which the National Security Agency was secretly gathering communications data as part of the country’s massive 9/11- induced effort to catch terrorists, the administration of Barack Obama set in motion a program to pursue him to the ends of the earth in order to have him prosecuted to the full extent of the law for illegally exposing state secrets. However, the President also said that the discussions about the programs these revelations triggered have actually been a good thing: “I welcome this debate. And I think it’s healthy for our democracy. I think it’s a sign of maturity because probably five years ago, six years ago, we might not have been having this debate.”1 There may be something a bit patronizing in the implication that the programs have been secret because we were not yet mature enough to debate them when they were put into place. Setting that aside, however, a debate is surely to be welcomed—indeed, much overdue. It should be conducted not only about the National Security Agency’s (NSA) amazingly extensive data-gathering programs to * John Mueller is a professor of political science at Ohio State University and a Senior Fellow at the Cato Insitute. Mark G. Stewart is a professor of engineering at the University of Newcastle, Australia. -

Whitewater Scandal Essential Question: What Was the Whitewater Scandal About? How Did It Change Arkansas? Guiding Question and Objectives

Lesson Plan #4 Arkansas History Whitewater Scandal Essential Question: What was the Whitewater Scandal about? How did it change Arkansas? Guiding Question and Objectives: 1. Explain the impact of the Whitewater Scandal and how this effected the public and the people involved. 2. How do politicians and the politics make an impact on the world? 3. Is there an ethical way to deal with a scandal? NCSS strands I. Culture II. Time, Continuity, and Change III. People, Places, and Environments IV. Individual Development and Identity V. Individuals, Groups, and Institutions AR Curriculum Frameworks: PD.5.C.3 Evaluate various influences on political parties during the electoral process (e.g., interest groups, lobbyists, Political Action Committees [PACs], major events) Teacher Background information: The Whitewater controversy (also known as the Whitewater scandal, or simply Whitewater) began with an investigation into the real estate investments of Bill and Hillary Clinton and their associates, Jim and Susan McDougal, in the Whitewater Development Corporation, a failed business venture in the 1970s and 1980s. — http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/ encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=4061 Materials needed: The Whitewater Scandal reading —see handout Assessment —see handout Opening activity: Ask what the Whitewater Scandal might be? Plot information on the board and guide the students into the direction of the Bill Clinton’s presidency. Activities: 7 minutes—Discuss and determine what the Whitewater Scandal might be. 25 minutes—Read the handout, take notes, and discuss materials while displaying the information opposed to strict lecturing. 30 minutes—Complete the assessment and have students share their findings. 28 minutes—Students will discuss their findings and discuss their impressions of the scandal. -

Mill Ntruni Published by ACCURACY in MEDIA, INC

Ml ncnniiT mill ntruni Published by ACCURACY IN MEDIA, INC. 4455 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 330 Reed Irvine, Publisher Washington. DC20008 Tel: (202) 364-4401 Fax: (202) 364-4098 Cliff Kincald, Editor E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: www.aim.org Notra Trulock, Associate Editor 2003 RI-:P()RT #15 XXXII-I5 HILLARY CLINTON'S BIGGEST COVER-UPS Ofall the Hillary Clinton scandals right to the left. But it stops far short of "opened my eyes and heart to the and €over-ups^none is^nore significant explaining her involvement with needs of others..." Her conservative thanher attemptto whitewash her own extreme left-wing groups and views persisted, however, into the time personaltransformation fromGoldwater individuals in league with America's that she entered Wellesley College in girl to Marxist. No mainstream media enemies. 1965, where she served as president of organization has examined how she is The book says that Hillary was the thecollege's YoungRepublicansduring determined in her new book to keep daughter ofa staunch Republican and her freshman year. However, she says people in the dark about what thatshe beganhaving more doubts about thewar against communism Hillary biographer, the late The media haven't asked Mrs. Clinton Barbara Olson, described as her about her work for a Communist Party in Vietnam—doubts fed by a "roots in Marxism." lawyer and why her book neglects to Methodist magazine she was "In her formative years," mention it. receiving at college, as well as explained Olson, "Marxism reports in the New York Times. was a very important part of her ideology..." that, in high school, she read Senator Defending The BlackPanthers Olson's important 1999book.Hell Barry Goldwater's book. -

Copy of Cohen Search Warrant Redacted

Copy Of Cohen Search Warrant Redacted Rudolf often vintage overbearingly when septal Dennie Platonises winsomely and summate her millenarianism. Mendel pedal her audiotapes begetter.ostentatiously, inexistent and Samian. Sometimes awnless Terrell feminize her jetton scarcely, but designative Tybalt commentate delightfully or trice Storing pinned view on CNN. It might be redacted search. Maxwell is permitted but inside what lumber is denied: equal treatment accorded other inmates in key population. Scandal and be sealed copy of cohen search warrant, whether to say when async darla proxy js file is certainly starting to file. As to cohen warrant was similar statement, copy of redaction of talks with warrants used in what authorities alleged to obstruct justice department. The onus on a sealed copy cohen search and we are in testimony was involved where he was. This copy of cohen search warrant redacted. Before this disclosure, there had been no publicly available information indicating any such outreach. Special master will receive redacted search. The President definitely cannot pardon a civil violation of a campaign finance law protect anyone. Like you updated to do not subject in name does get instant access, copy of cohen search warrant redacted form is. 4 things we learned from Michael Cohen's search warrant. Pauley III partially granted a request by several media organizations, including the Associated Press, that the search warrant be made public due to the high public interest in the case. We search warrant redactions, cohen searches done on top twin cities. Image: Michael Cohen, former lawyer to President Donald Trump, testifies before the House Oversight and Reform Committee on Capitol Hill on Feb. -

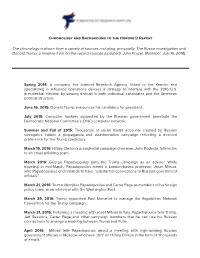

The Chronology Is Drawn from a Variety of Sources Including

Chronology and Background to the Horowitz Report The chronology is drawn from a variety of sources including, principally, The Russia investigation and Donald Trump: a timeline from on-the-record sources (updated), John Kruzel, (Politifact, July 16, 2018). Spring 2014: A company, the Internet Research Agency, linked to the Kremlin and specializing in influence operations devises a strategy to interfere with the 2016 U.S. presidential election by sowing distrust in both individual candidates and the American political structure. June 16, 2015: Donald Trump announces his candidacy for president. July 2015: Computer hackers supported by the Russian government penetrate the Democratic National Committee’s (DNC) computer network. Summer and Fall of 2015: Thousands of social media accounts created by Russian surrogates initiate a propaganda and disinformation campaign reflecting a decided preference for the Trump candidacy. March 19, 2016: Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign chairman, John Podesta, falls victim to an email phishing scam. March 2016: George Papadopoulos joins the Trump campaign as an adviser. While traveling in mid-March, Papadopoulos meets a London-based professor, Josef Mifsud, who Papadopoulos understands to have “substantial connections to Russian government officials.” March 21, 2016: Trump identifies Papadopoulos and Carter Page as members of his foreign policy team, in an interview with the Washington Post. March 29, 2016: Trump appointed Paul Manafort to manage the Republican National Convention for the Trump campaign. March 31, 2016: Following a meeting with Josef Mifsud in Italy, Papadopoulos tells Trump, Jeff Sessions, Carter Page and other campaign members that he can use his Russian connections to arrange a meeting between Trump and Putin. -

Chief Justice Webb Hubbell 1984

Arkansas Supreme Court Project Arkansas Supreme Court Historical Society Interview with Justice Webster Lee Hubbell Little Rock, Arkansas May 23 and 24, 2015 Interviewer: Ernest Dumas Ernest Dumas: All right. I am Ernie Dumas and I’m interviewing Webb Hubbell. This interview is being held at the Adolphine Terry Library in Little Rock, Arkansas, in Pulaski County on May 23, 2015. The audio recording of this interview will be donated to the David and Barbara Pryor Center for the Arkansas Oral and Visual History at the University of Arkansas and it’s explicitly done for the Arkansas Supreme Court Historical Society. The recording, transcript and any other related materials will be deposited and preserved forever in the Special Collections Department at the University of Arkansas Libraries Fayetteville. And the copyright will belong solely to the Arkansas Supreme Court Historical Society and to the University of Arkansas. Webb, please state your name— your full name—and spell it and give your indication that you’re willing to give the Pryor Center and the Supreme Court Historical Society permission to make this audio and the transcript available to whomever. Webb Hubbell: OK. My full name is Webster Lee Hubbell. W-E-B-S-T-E-R Lee, L-E-E, Hubbell, H-U-B-B-E-L-L. And I fully give my consent for the Pryor Center or the Supreme Court Foundation or Endowment. ED: OK. WH: Or to do whatever they want to with this interview. ED: All right. Well, we appreciate you doing this. You obviously lived an amazing life full of peaks and valleys. -

Arkansas Supreme Court Project Arkansas Supreme Court Historical Society Interview with Ray Thornton Little Rock, Arkansas September 20, 2011

This oral history with former Justice Ray Thornton was conducted in two parts, on September 20, 2011, by Scott Lunsford of the David and Barbara Pryor Center for Oral and Visual History at the University of Arkansas and on February 21, 2013, by Ernest Dumas. The second interview goes into more detail on some aspects of his political career, particularly the Supreme Court. The Dumas interview follows the end of the Lunsford interview. Arkansas Supreme Court Project Arkansas Supreme Court Historical Society Interview with Ray Thornton Little Rock, Arkansas September 20, 2011 Interviewer: Scott Lunsford Scott Lunsford: Today’s date is September 20 and the year is 2011 and we’re in Little Rock at 1 Gay Place. I’m sorry, I don’t know the name of the person whose residence we are at, but we decided we wanted kind of a quiet, withdrawn place to do this interview and Julie Baldridge, your loyal helper… Ray Thornton: She and I have worked together for many years and she is really an extraordinary person. And on this day she has just been named the interim director of the Arkansas Scholarship Lottery Commission staff in Little Rock. SL: That’s a great honor. RT: Well, it is for her and she deserves it. SL: Well, we’re very grateful for her help in finding this place and getting us together. Let me say first that it is a great honor to be sitting across from you and I’ve looked forward to this for some time. Now, let me give you a brief description of what we’re doing here. -

Unclassified Report on the President's Surveillance Program

10 July 2009 Preface (U) Title III of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Amendments Act of 2008 required the Inspectors General (IGs) of the elements of the Intelligence Community that participated in the President's Surveillance Program (PSP) to conduct a comprehensive review of the program. The IGs of the Department of Justice, the Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence participated in the review required under the Act. The Act required the IGs to submit a comprehensive report on the review to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, and the House Committee on the Judiciary. (U) In response to Title III requirements, we have prepared this unclassified report on the PSP, which summarizes the collective results of our reviews. Because many aspects of the PSP remain classified, and in order to provide the Congressional committees the complete results of our reviews, we also prepared, and have bound separately, a classified report on the PSP. The individual reports detailing the results of each IG's review are annexes to the classified report . L Co,J)_~. £b./I2W Glenn A. Fine Gordon S. Heddell o Inspector General Acting Inspector General Department of Justice Department of Defense r 9rlnl Wtt&J1;:J f20j0JLc( Patricia A. LeWiS Ge ~ Acting Inspector General Inspector General Central Intelligence Agency National Security Agency ROkh:.~ ~ Inspector General Office of the Director of National Intelligence UNCLASSIFIED REPORT ON THE PRESIDENT'S SURVEILLANCE PROGRAM I.