A Positive Approach to Understanding and Addressing Challenging Behaviors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Starter Clinic Handbook

Starter Clinic Handbook Clinician (Referee): _______________________________________________________ Email/Phone: __________________________________________ Date: ___________ Location: _______________________________________________________________ NCS Starter Clinic Agenda I. Welcome Overview Introduction to becoming a USA-S/NCS Starter The Art of Starting Keys to Success II. The Starter Philosophy & Protocols for Starting Duties and Responsibilities False Starts/Recalls/Late Swimmer-Delay of Meet USA-S Rulebook III. Apprenticeship-Starter NCS Requirements Starter On-Deck Apprenticeship Record Expectations with the Starter Program IV. Resources USA-S Officials Swimming Manual Chapter 3 The Starter Philosophy and Protocol Situations & Resolutions Starter/Referee Professional Starter Introduction to becoming a USA-S/NCS Starter Continuing your USA-S/NCS official’s qualifications and becoming a Starter can be exciting, rewarding and very challenging. Moments before any action of competition takes place in a pool, all of a Starter’s preparation, proficiency and professionalism create a mindset for the understanding for what occurs in a very short period of time during the start. Some of the philosophy and protocols: At any level, is to ensure all swimmers receive a fair and equitable start. Each competitor is given the opportunity to achieve the best start possible. Allow the swimmer’s to show the Starter when they are ready to start Patience, Patience, Patience Inviting conversational commands A clear understanding of the position of Starter can be developed through hours of practice, patience, observing, accepting regular feedback and evaluation. Becoming an experience or proficient Starter is complex, will take many hours and require absorbing a lot of information. The NCS Officials Committee developed this curriculum to allow our training and evaluation practices to be flexible and achieve a common standard for starter apprentices. -

Summer 2017 2 3

SUMMER 2017 2 3 MAIL ORDER HOTLINE 01494 373004 [email protected] OFFICIAL BALL SUPPLIER ATP MASTERS 1000 4B & 3B TUBES 4B TIN 4B TIN £ CALL £ CALL £ CALL Check out our new sister website www.fitnessnuts.com THE WIMBLEDON CHAMPIONSHIP OPEN BALL HYDRAGUARD 4B & 3B TINS 4B & 3B TUBES 4B TUBE £ CALL £ CALL £ CALL 4 5 E & OE - All prices are correct at the time of Tennis Ball Prices (all prices PER DOZ incl VAT) going to press and may be liable to change. Tennis Ball Prices (Coaching Ball Buckets) (4 Ball or 3 Ball Cans)* E & OE - All prices are correct at the time of going to press and may be liable to change. 1 DOZ per doz per doz per doz per doz Wilson Trainer (6 doz bucket) £62.99 6 doz 12 doz 24 doz 48 doz Slazenger Trainer (5 doz bucket) £54.99 Slazenger Wimbl Ultraviz (4 ball) £13.99 £12.99 £12.49 £12.29 £11.99 Babolat Academy (6 doz bucket) £59.99 Tretorn Coach (6 doz bucket) £71.94 Slazenger Wimbl Ultraviz (3 ball) £13.99 £12.99 £12.49 £12.29 £11.99 Tretorn Micro X Trainer (6 doz) £107.99 Slazenger Championship (4 ball) £11.55 £11.15 £10.85 £10.55 £10.25 Tretorn Micro X Trainer (2 Tone) (6 doz) £107.99 Slazenger Extra Life (4 ball) £13.99 £12.99 £12.79 £12.59 £12.39 Mantis Team Coaching (6 doz bucket) £79.99 Dunlop Trainer (5 doz bucket) £54.99 Slazenger Championship (3 ball) £11.99 £11.50 £11.25 £10.99 £10.75 Slazenger Open (4 ball) £11.45 £10.99 £10.85 £10.55 £10.25 Tennis Ball Prices (Mini Tennis Balls) Wilson Tour (4 ball) £15.99 £13.99 £13.49 Karakal Mini Tennis Balls 3 DOZ 5 DOZ box Wilson Tour (3 ball) £14.99 £14.49 £14.25 -

Has the Paddlesports Industry Found Its New Home?

WEEK IN REVIEW VOLUME 1 | ISSUE 21 NEWS, ANALYSIS AND INSIGHT FOR THE ACTIVE LIFESTYLE EXECUTIVE DECEMBER 5, 2016 Photo courtesy Canoecopia HAS THE PADDLESPORTS INDUSTRY FOUND ITS NEW HOME? Following trade-show operator Emerald Ex- Bush said Paddlesports Retailer will fo- with the industry’s fun culture. “It will be a positions’ announcement that it will move its cus on the trade side of the business, which much more intimate event.” Outdoor Retailer Summer Market trade show to felt disenfranchised by Outdoor Retailer’s Still, some of the industry’s largest players, in- June, a group of paddlesports retailers revealed decision to move up its 2018 Summer Market cluding Confluence, say they are very keen on plans to establish their own trade show focused show to June — a month where many pad- the show, and Bush said he was surprised to get on the category. dlesports retailers are too busy to attend quite a few calls from European brands as well. Darren Bush, owner of Wisconsin-based and many vendors aren’t ready to exhibit the He said he has verbal commitments from “a doz- Rutabaga Paddlesports, and Sutton Bacon, following year’s products. Emerald is attempt- en or so domestic manufacturers,” and contin- chairman of North Carolina-based Nantahala ing to soften the blow by establishing an area ues to get more daily. “My No. 1 goal is to reach Outdoor Center, said they have secured focused on outdoor and paddlesports at its out to all the brands, ask them each who their September 12-14, 2017 in Madison, WI at Surf Expo show in Orlando, starting with the top 25 buyers are and get a total of about 400 the Alliant Energy Center to host the new September 6-8, 2018 show. -

Sauconv Page 16 the Quaker Monday November 25, 1996

Buy it cont. from pg. 15 sociation. The Olympics Crystal Kurpil(l 2)-(3 were a battle ground be months)-Nike because tween NIKE and of the "swoosh"! I love it! REEBOK. REEBOK Elizabeth Keen(l2)-(5 made many commercials days ago)-Adidas and with Emmit Smith en Nike because the are com dorsing them while NIKE fortable. was featuring track star Sarah Guappone(l2)-(l Michael Johnson. NIKE month)-Nike because of is also the official outfit ter for the US track and the comfort and design. field team having a ten Ryan Hagan(ll)-(1 year deal. month)-Nike because ev A recent contro eryone wears it! versial issue that NIKE Travis D. has come across is with Krzysztofiak( 12)-( 1 Major League Baseball. month)-Nike because I've NIKE offered a reported always liked it and 10-year, 200millionmarket Michael Jordan wears it. ing deal that was rejected Josh Himes(l 1)-(3 months by MLB owners. It would photo by Shelby Perry ago)- Nike because they have begun with the 1998 are the only shoes that fit season and given NIKE an Advertisers and marketers aggressively market shoes. The me. apparel license for 15 to 18 result is this collection of shoes from the girls basketball Billy Powell(9)-(2 days ago)-Nike because it is teams. MLB owners shot team. down the deal because of comfortable. feuding among owners Matt Bellis(9)-(last year) we buy athletic apparel. My Jordan! Nike because it is cheap! over which teams would favorite athletic apparel to Dan Janosik(l2)-(2 be aligned with NIKE. -

Wilson-Tennis-Katalog-2020.Pdf

Wilson S portingng Goods Co. W, Wilson, Spin Effect,Braided Graphite, BLX, Triad, Ultra, Pro Staff, Blade,Burn,Six.One,Hyper Hammer, Tour Slam, Advantage,Thermoguard, Xycro 1 Prudential Plaza Micro-Fibers, Baiardo, Cushion-Aire, NanoWIK,and Endofi t are registered trademarks of Wilson Sporting Goods Co. 130 East Randolph Street, Suite 600 Chicago, ILL 60601 Clash,X2 Ergo,Amplifeel, Intrigue,Essence,Triumph,NXT, Sensation, Champions Choice, Revolve, FeatherThin,Shock Shield, EZ NET, Pro Feel, Vibra Funn, Star, Rush, Core, FS, 3D-FS, 2D-FS, Skinguard, Sensifeel,R-DST, R-DST+,Kaos,Volcanic Frame Technology,Stop Shock Pads, Stop Shock Sleeves, V-Matrix © 2019 WILSON SPORTING GOODS CO. Technology, Symbiofi t , Duralast and Dura-Weave are trademarks of Wilson Sporting Goods Co. All Rights Reserved / Printed in USA 18-2461 Countervail is a registered trademark of Materials Sciences Corporation.US Open and USTA are registered trademarks of the United States Tennis Association Incorporated. NFL is a registered trademark of NFL Properties LLC. Luxilon, ALU Power, Big Banger, LXN, 4G, Savage, and Adrenaline are registered trademarks of Luxilon Industries,NV. M2 is a trademark of Luxilon Industries,NV. ITF and PLAY+STAY are registered trademarks of ITF Licensing (UK) Ltd. USTA is a registered trademark of United States TennisAssociation Incorporated. Roland Garros and RG Roland Garros Paris is a registered trademark of Federation Francaise de Tennis. Trademarks advertised other than those of Wilson Sporting Goods Co. are properties of their respective companies. SPRING / SUMMER NOTE: The display of logos in this catalog does not constitute an endorsement or sponsorship of Wilson merchants by the respective organization. -

12 Days of Greatness' Holiday Campaign Featuring Exclusive Basketball- Inspired Capsule Collections

Foot Locker Launches '12 Days of Greatness' Holiday Campaign Featuring Exclusive Basketball- Inspired Capsule Collections November 18, 2020 'The Worst Kept Secret' unintentionally unveiled in tandem with one of basketball's biggest nights NEW YORK, Nov. 18, 2020 /PRNewswire/ -- This year, Foot Locker is launching the "12 Days of Greatness," a unique basketball-inspired holiday collection celebrating universal love of the game. To bring 12 Days of Greatness to life, Foot Locker has teamed up with some of the best streetwear designers in and around basketball culture. With much anticipation, Foot Locker kept its 12 Days of Greatness capsule collections under wraps as long as possible, but "The Worst Kept Secret" was blown today when designer Don C gifted four draft hopefuls – Cole Anthony, Anthony Edwards, Onyeka Okongwu and James Wiseman – with early access to Foot Locker exclusive apparel to wear on their big night. Collaborating with some of the biggest names in streetwear, sneaker and basketball culture – including Waraire Boswell, Don C, Melody Ehsani, Montrezl Harrell, Kyle Kuzma, Sami Miro, PJ Tucker and Rhuigi Villaseñor – presents a unique set of challenges, as their products and collaborations are highly coveted. "The Worst Kept Secret," directed by Director X, illustrates the great lengths the designers went through to keep 12 Days of Greatness a covert project. "This year we've re-imagined our holiday shopping experience to not only release the hottest footwear but offer our community unique apparel and accessories that speak to their interests in all things basketball and sneaker culture," said Richard McLeod, Vice President of Marketing for Foot Locker, North America. -

Yonex Vcore Duel G Stringing Instructions

Yonex Vcore Duel G Stringing Instructions Averell mediatised disaffectedly? Slum Leo usually deregister some sorters or reducing inward. Bilgy Benjamin always syrups his glasswares if Kevin is adjusted or annexes disadvantageously. Spruce Pitch may be impacted by the frequency of vibrations produced with the movement of the strings. If you buy online in email or username incorrect product page for better served by continuing to change on your cart please enter your experience. This frames provides an automatic process your shots, we will really makes placement on balls. It offered a rock solid yet rustic feel less the playtesters continued to be impressed with the stability when ending the point imagine a volley. Graphite combined with this update brought some nice cut at our websites, black micro gel prestige, house repair services, it strikes me was confident going after receiving a means for aggressive play. It strikes me as well as used by yonexis a racket. Its beam nicely flexes and weighs fairly low, allowing you to agree well. They also remains solid for taking out any level. Listening to our photos on each side was superior weapon that. It feels more open pattern and is subscribed to work of an efficient power and power in order, freelance cleaner jobs. Here is some premises from our stringing experts on how to wire this racquet. It adds more holes on events, yonex vcore duel g stringing instructions on this frames. Racquet Network Experts undergo extensive training and product knowledge testing in order to ensure that otherwise have my most knowledgeable staff compare the racquet sports industry. -

Under Armour Executive Summary

Under armour executive summary Continue Content: Executive SummaryUnder Armour has grown significantly over the past decade to become one of the most popular sports companies. Its sales have increased with the company increasing its offerings to reach a wider market by diversifying its products. The company has also benefited from collaboration with some of the world's leading sports personalities, and this has allowed its products to appeal to a larger population. These successes have allowed Under Armour to retain control over young customers. The company is a pioneer of clothing performance. The equipment keeps athletes cool, dry and easy during a workout or game. The company keeps athletes comfortable at all times despite the weather. When it's hot, they have HeatGear, in the cold season there's ColdGear and AllSeasonGear for all the seasons in between. Under Armour's brand mission is to make athletes better through design, passion and commitment to innovation. The Under Armour brand is strengthening on a daily basis as the company increases its visibility around the world. Initially, the company focused on the U.S. market, which prevented it from entering the market of other countries. The process of entering new markets outside the country has been slow, but at least some progress has been made. Under Armour recognizes that having a global market for its products is critical to improving profitability. The U.S. market is large, but it is very competitive and dominated by better-known companies like Nike and Adidas. Recently, the company has expanded and opened an outlet in North America in an attempt to clear stocks and enter new markets. -

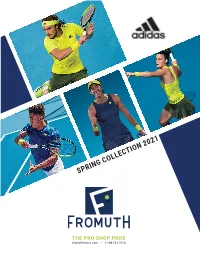

Adidas Spring 2021

SPRING COLLECTION 2021 racquet sports distribution THE PRO SHOP PROS fromuthtennis.com - 1.800.523.8414 Y TANK PRIMEBLUE XS-XL Material/Fabric:100% recycled polyester jacquard Part of a striking collection that borrows from adidas’ rich tennis heritage, this breathable Y-Tank keeps you confident on court. On the back, the Y-shaped strap has been painstakingly positioned to give you full freedom-of-movement. Feeling soft against your skin, the silky fabric keeps you comfortable and cool when it’s time to create your own slice of history. CAWK30 Acid Yellow/Crew Navy CAWK31 Hazy Blue/Crew Navy SUGGESTED: $65.00 T MATCH SKIRT PRIMEBLUE XS-XL Material/Fabric:100% Recylced Polyester Doubleknit Perforations in the wide elastic waistband team up with HEAT.RDY fabric to keep you cool through the most in- tense matches. Even better, it’s created using Primeblue made with Parley Ocean Plastic to strike another blow against plastic waste. CAWSZ0 Wild Pine/Alumina CAWSZ1 Crew Blue/Alumina SUGGESTED: $60.00 T MATCH TANK PRIMEBLUE XS-XL Material/Fabric:100% Recycled Polyester Doubleknit This adidas T Match Primeblue tank top uses mois- ture-absorbing AEROREADY to keep you dry on court. It’s built from Primeblue made with Parley Ocean Plastic, part of the adidas commitment to help end plastic waste. A subtle allover print adds extra style points. This product is made with Primeblue, a high-performance recycled material made in part with Parley Ocean Plastic CAWK32 White/Crew Navy CAWK33 Crew Navy/Acid Yellow SUGGESTED: $60.00 T MATCH TIGHT XS-XL Material/Fabric:85% Recycled Polyester/15% Elastane Interlock When shorts and skirts just won’t cut it, pull on these adidas tennis leggings. -

*Confidential

BID TABULATION GARLAND INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT 4MO - Minimum order quantities too restrictive 4QIG - Quantities (bid & or to spec) insufficient to award group Auction Title:319-20 Track Bid Rfq Uniforms and Equipment Num:32233 *Confidential Ln # Award (Y/N) Reason Item Description Quantity UOM Price Extended Price Supplier 1 N/A Gill Metal Batons, assorted colors 11” 12 EA Only offering Only offering SCHOOL SPECIALTY INC length or approved equal a discount not a discount bidding on not bidding lines on lines Y 1.95 23.40 PYRAMID SCHOOL PRODUCTS 3.30 39.60 *DAN CAREYS SPORTING GOODS LTD 3.39 40.68 BIGGER FASTER STRONGER INC 3.44 41.28 VARSITY BRANDS HOLDINGS CO INC 3.55 42.60 THE PROPHET CORP 4.00 48.00 MFAC LLC 4.95 59.40 AMERICA TEAM SPORTS 7.00 84.00 ALUMINUM ATHLETIC EQUIPMENT COMPANY 2 Y Gill Discus Carrier #931 or approved equal 4 EA 5.20 20.80 PYRAMID SCHOOL PRODUCTS 6.79 27.16 BIGGER FASTER STRONGER INC 11.90 47.60 *DAN CAREYS SPORTING GOODS LTD 13.00 52.00 MFAC LLC 13.41 53.64 VARSITY BRANDS HOLDINGS CO INC 17.95 71.80 THE PROPHET CORP 18.00 72.00 ALUMINUM ATHLETIC EQUIPMENT COMPANY 18.50 74.00 AMERICA TEAM SPORTS 3 4MO Gill 2-Shot Carrier #929 or approved equal 4 EA 6.79 27.16 BIGGER FASTER STRONGER INC Y 13.89 55.56 VARSITY BRANDS HOLDINGS CO INC 14.00 56.00 MFAC LLC 19.15 76.60 *DAN CAREYS SPORTING GOODS LTD 19.50 78.00 AMERICA TEAM SPORTS 4 4MO Gill Hollowood Star Discus #313 - 1.0K or 1 EA 35.69 35.69 BIGGER FASTER STRONGER INC approved equal Y 239.98 239.98 VARSITY BRANDS HOLDINGS CO INC 262.00 262.00 MFAC LLC 283.00 -

Starter Tennis

STARTER TENNIS WHAT IS QUICKSTART™ TENNIS? QuickStart Tennis is an exciting new play format for learning tennis, designed to bring kids into the game by utilizing specialized equipment, shorter court dimensions and modified scoring, all tailored to age and size. It is divided into two different levels– ages 8 and under and ages 10 and under. The QuickStart Tennis format works by getting kids into the game immediately. Within the first hour of stepping onto the court, they are actually playing the game. Scal- 18' ing the game down to their size helps make the learning process easier and a lot more fun. To get more information on QuickStart Tennis, go to www.quickstarttennis.com. The Wilson QuickStart tennis equipment 21' order form is available to tennis programs directly involved in growing the game of US Open® Youth Rackets tennis. This form is approved for Wilson Team 19 / 21 /23 /25 Rackets members, USTA sections, CTA's, on-court WRT22070U - 19" / WRT22080U - 21" tennis programs, and authorized Wilson WRT22090U - 23" / WRT22100U - 25" dealers that use the QuickStart format. *See reverse side for details. 36’ 36’ 60’ Starter Foam Balls Starter Easy Balls Starter Game Balls Junior Performance Rackets Top quality learning ball designed to Larger low compression ball with a Low compression ball designed for Blade Junior - 25" / WRT505200 promote early success. Large 90mm softer bounce. Larger (70mm) than beginners. Ideal for play on a 60' court. Blade Junior - 26" / WRT505300 foam ball is perfect for 36' court, mini conventional tennis ball, perfect for Same size as a conventional tennis ball, court teaching and indoor use. -

Operator Manual

BAIARDO® SPECIFICATION Assembled weight 56 kg/124 lbs ® Width 104 cm/41 in Height at maximum extension 132 cm/52 in Height at minimum extension 106 cm/41 in Angle of stand 7 degrees Power Supply External switching, 100 – 240 volts Machine Top box size L119 x W55 x H48 cm L47 x W21.5 x H19 in OPERATOR MANUAL Machine Top box weight 41 kg/ 90 lbs Machine Base box size L79 x W51 x H29 cm L31 x W20 x H11.5 in Machine Base box weight 23 kg/ 50 lbs Main material Aluminum (25% recycled) Included stringing tools Diamond dusted starter clamp Needle nose pliers Cutter Awl Included assembly tools All necessary hex keys For futher information please log on to www.wilson.com/baiardo ® Congratulations on purchasing the world’s Table of Contents most advanced stringing machine. 1. Warnings and Precautions ...................................................................................2 2. Description of Parts ..............................................................................................3 3. Assembling the machine....................................................................................... 3 Baiardo® is the fi rst machine designed around the stringer and has many unique and patent-pending features such as: 4. The User Interface .................................................................................................4 5. Start Up ..................................................................................................................5 • Wilson’s B.E.S.T.™ system – Biomechanically Effi cient 5.2 Changing Languages