An Explanation of Negative Swap Spreads: Demand for Duration from Underfunded Pension Plans by Sven Klingler and Suresh Sundaresan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interest Rate Options

Interest Rate Options Saurav Sen April 2001 Contents 1. Caps and Floors 2 1.1. Defintions . 2 1.2. Plain Vanilla Caps . 2 1.2.1. Caplets . 3 1.2.2. Caps . 4 1.2.3. Bootstrapping the Forward Volatility Curve . 4 1.2.4. Caplet as a Put Option on a Zero-Coupon Bond . 5 1.2.5. Hedging Caps . 6 1.3. Floors . 7 1.3.1. Pricing and Hedging . 7 1.3.2. Put-Call Parity . 7 1.3.3. At-the-money (ATM) Caps and Floors . 7 1.4. Digital Caps . 8 1.4.1. Pricing . 8 1.4.2. Hedging . 8 1.5. Other Exotic Caps and Floors . 9 1.5.1. Knock-In Caps . 9 1.5.2. LIBOR Reset Caps . 9 1.5.3. Auto Caps . 9 1.5.4. Chooser Caps . 9 1.5.5. CMS Caps and Floors . 9 2. Swap Options 10 2.1. Swaps: A Brief Review of Essentials . 10 2.2. Swaptions . 11 2.2.1. Definitions . 11 2.2.2. Payoff Structure . 11 2.2.3. Pricing . 12 2.2.4. Put-Call Parity and Moneyness for Swaptions . 13 2.2.5. Hedging . 13 2.3. Constant Maturity Swaps . 13 2.3.1. Definition . 13 2.3.2. Pricing . 14 1 2.3.3. Approximate CMS Convexity Correction . 14 2.3.4. Pricing (continued) . 15 2.3.5. CMS Summary . 15 2.4. Other Swap Options . 16 2.4.1. LIBOR in Arrears Swaps . 16 2.4.2. Bermudan Swaptions . 16 2.4.3. Hybrid Structures . 17 Appendix: The Black Model 17 A.1. -

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: Analysing the Super-Senior Swap Element

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: analysing the Super-Senior Swap element Nicoletta Baldini * July 2003 Basic Facts In a typical cash flow securitization a SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) transfers interest income and principal repayments from a portfolio of risky assets, the so called asset pool, to a prioritized set of tranches. The level of credit exposure of every single tranche depends upon its level of subordination: so, the junior tranche will be the first to bear the effect of a credit deterioration of the asset pool, and senior tranches the last. The asset pool can be made up by either any type of debt instrument, mainly bonds or bank loans, or Credit Default Swaps (CDS) in which the SPV sells protection1. When the asset pool is made up solely of CDS contracts we talk of ‘synthetic’ Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs); in the so called ‘semi-synthetic’ CDOs, instead, the asset pool is made up by both debt instruments and CDS contracts. The tranches backed by the asset pool can be funded or not, depending upon the fact that the final investor purchases a true debt instrument (note) or a mere synthetic credit exposure. Generally, when the asset pool is constituted by debt instruments, the SPV issues notes (usually divided in more tranches) which are sold to the final investor; in synthetic CDOs, instead, tranches are represented by basket CDSs with which the final investor sells protection to the SPV. In any case all the tranches can be interpreted as percentile basket credit derivatives and their degree of subordination determines the percentiles of the asset pool loss distribution concerning them It is not unusual to find both funded and unfunded tranches within the same securitisation: this is the case for synthetic CDOs (but the same could occur with semi-synthetic CDOs) in which notes are issued and the raised cash is invested in risk free bonds that serve as collateral. -

A Guide for Investors

A GUIDE FOR INVESTORS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 MAIN RISKS 7 Business risk or intrinsic risk 7 Economic risk 7 1 Inflation risk 7 Country risk 7 Currency risk 7 Liquidity risk 7 Psychological risk 7 Credit risk 7 Counterparty risk 8 Additional risks associated with emerging markets 8 Other main risks 8 BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF CERTAIN TYPES OF INVESTMENT AND SPECIFIC ASSOCIATED RISKS 9 Time deposits 9 2 Bonds 9 A. Characteristics of classic bonds 9 B. Convertible bonds 9 C. CoCo type bonds 9 D. Risks 9 Equities 10 A. Characteristics 10 B. Risks 10 Derivatives 10 A. Options 11 B. Warrants 11 C. Futures 11 D. Risks 11 Structured products 11 A. Characteristics 11 B. Risks 11 C. Reverse convertibles 11 Investment funds 12 A. General risks 12 B. Categories 12 1. Money market funds 12 2. Bond funds 12 3. Equity funds 12 4. Diversified/profiled funds 12 5. Special types of funds 12 A. Sector funds 12 B. Trackers 12 C. Absolute return funds 13 Page 3 of 21 CONTENTS D. Alternative funds 13 1. Hedge funds 13 2. Alternative funds of funds 13 E. Offshore funds 13 F. Venture capital or private equity funds 14 Private Equity 14 A. Caracteristics 14 B. Risks 14 1. Risk of capital loss 14 2. Liquidity risk 14 3. Risk related to the valuation of securities 14 4. Risk related to investments in unlisted companies 14 5. Credit risk 14 6. Risk related to “mezzanine” financing instruments 14 7. Interest rate and currency risks 14 8. Risk related to investment by commitment 15 3 GLOSSARY 16 Any investment involves the taking of risk. -

3. VALUATION of BONDS and STOCK Investors Corporation

3. VALUATION OF BONDS AND STOCK Objectives: After reading this chapter, you should be able to: 1. Understand the role of stocks and bonds in the financial markets. 2. Calculate value of a bond and a share of stock using proper formulas. 3.1 Acquisition of Capital Corporations, big and small, need capital to do their business. The investors provide the capital to a corporation. A company may need a new factory to manufacture its products, or an airline a few more planes to expand into new territory. The firm acquires the money needed to build the factory or to buy the new planes from investors. The investors, of course, want a return on their investment. Therefore, we may visualize the relationship between the corporation and the investors as follows: Capital Investors Corporation Return on investment Fig. 3.1: The relationship between the investors and a corporation. Capital comes in two forms: debt capital and equity capital. To raise debt capital the companies sell bonds to the public, and to raise equity capital the corporation sells the stock of the company. Both stock and bonds are financial instruments and they have a certain intrinsic value. Instead of selling directly to the public, a corporation usually sells its stock and bonds through an intermediary. An investment bank acts as an agent between the corporation and the public. Also known as underwriters, they raise the capital for a firm and charge a fee for their services. The underwriters may sell $100 million worth of bonds to the public, but deliver only $95 million to the issuing corporation. -

Summary Prospectus

Summary Prospectus KFA Dynamic Fixed Income ETF Principal Listing Exchange for the Fund: NYSE Arca, Inc. Ticker Symbol: KDFI August 1, 2021 Before you invest, you may want to review the Fund’s Prospectus, which contains more information about the Fund and its risks. You can find the Fund’s Prospectus, Statement of Additional Information, recent reports to shareholders, and other information about the Fund online at www.kfafunds.com. You can also get this information at no cost by calling 1-855-857-2638, by sending an e-mail request to [email protected] or by asking any financial intermediary that offers shares of the Fund. The Fund’s Prospectus and Statement of Additional Information, each dated August 1, 2021, as each may be amended or supplemented from time to time, and recent reports to shareholders, are incorporated by reference into this Summary Prospectus and may be obtained, free of charge, at the website, phone number or email address noted above. As permitted by regulations adopted by the Securities and Exchange Commission, paper copies of the Funds’ shareholder reports will no longer be sent by mail, unless you specifically request paper copies of the reports from the Funds (if you hold your Fund shares directly with the Funds) or from your financial intermediary, such as a broker-dealer or bank (if you hold your Fund shares through a financial intermediary). Instead, the reports will be made available on a website, and you will be notified by mail each time a report is posted and provided with a website link to access the report. -

Ice Crude Oil

ICE CRUDE OIL Intercontinental Exchange® (ICE®) became a center for global petroleum risk management and trading with its acquisition of the International Petroleum Exchange® (IPE®) in June 2001, which is today known as ICE Futures Europe®. IPE was established in 1980 in response to the immense volatility that resulted from the oil price shocks of the 1970s. As IPE’s short-term physical markets evolved and the need to hedge emerged, the exchange offered its first contract, Gas Oil futures. In June 1988, the exchange successfully launched the Brent Crude futures contract. Today, ICE’s FSA-regulated energy futures exchange conducts nearly half the world’s trade in crude oil futures. Along with the benchmark Brent crude oil, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil and gasoil futures contracts, ICE Futures Europe also offers a full range of futures and options contracts on emissions, U.K. natural gas, U.K power and coal. THE BRENT CRUDE MARKET Brent has served as a leading global benchmark for Atlantic Oseberg-Ekofisk family of North Sea crude oils, each of which Basin crude oils in general, and low-sulfur (“sweet”) crude has a separate delivery point. Many of the crude oils traded oils in particular, since the commercialization of the U.K. and as a basis to Brent actually are traded as a basis to Dated Norwegian sectors of the North Sea in the 1970s. These crude Brent, a cargo loading within the next 10-21 days (23 days on oils include most grades produced from Nigeria and Angola, a Friday). In a circular turn, the active cash swap market for as well as U.S. -

Tax Treatment of Derivatives

United States Viva Hammer* Tax Treatment of Derivatives 1. Introduction instruments, as well as principles of general applicability. Often, the nature of the derivative instrument will dictate The US federal income taxation of derivative instruments whether it is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset is determined under numerous tax rules set forth in the US (see discussion of section 1256 contracts, below). In other tax code, the regulations thereunder (and supplemented instances, the nature of the taxpayer will dictate whether it by various forms of published and unpublished guidance is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset (see discus- from the US tax authorities and by the case law).1 These tax sion of dealers versus traders, below). rules dictate the US federal income taxation of derivative instruments without regard to applicable accounting rules. Generally, the starting point will be to determine whether the instrument is a “capital asset” or an “ordinary asset” The tax rules applicable to derivative instruments have in the hands of the taxpayer. Section 1221 defines “capital developed over time in piecemeal fashion. There are no assets” by exclusion – unless an asset falls within one of general principles governing the taxation of derivatives eight enumerated exceptions, it is viewed as a capital asset. in the United States. Every transaction must be examined Exceptions to capital asset treatment relevant to taxpayers in light of these piecemeal rules. Key considerations for transacting in derivative instruments include the excep- issuers and holders of derivative instruments under US tions for (1) hedging transactions3 and (2) “commodities tax principles will include the character of income, gain, derivative financial instruments” held by a “commodities loss and deduction related to the instrument (ordinary derivatives dealer”.4 vs. -

An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming John Jackson Ada Li Asani Sarkar Patricia Zobel Staff Report No. 557 March 2012 Revised October 2012 FRBNY Staff REPORTS This paper presents preliminary fi ndings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily refl ective of views at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming, John Jackson, Ada Li, Asani Sarkar, and Patricia Zobel Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 557 March 2012; revised October 2012 JEL classifi cation: G12, G13, G18 Abstract This paper examines the over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate derivatives (IRD) market in order to inform the design of post-trade price reporting. Our analysis uses a novel transaction-level data set to examine trading activity, the composition of market participants, levels of product standardization, and market-making behavior. We fi nd that trading activity in the IRD market is dispersed across a broad array of product types, currency denominations, and maturities, leading to more than 10,500 observed unique product combinations. While a select group of standard instruments trade with relative frequency and may provide timely and pertinent price information for market partici- pants, many other IRD instruments trade infrequently and with diverse contract terms, limiting the impact on price formation from the reporting of those transactions. -

A Glossary of Securities and Financial Terms

A Glossary of Securities and Financial Terms (English to Traditional Chinese) 9-times Restriction Rule 九倍限制規則 24-spread rule 24 個價位規則 1 A AAAC see Academic and Accreditation Advisory Committee【SFC】 ABS see asset-backed securities ACCA see Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, The ACG see Asia-Pacific Central Securities Depository Group ACIHK see ACI-The Financial Markets of Hong Kong ADB see Asian Development Bank ADR see American depositary receipt AFTA see ASEAN Free Trade Area AGM see annual general meeting AIB see Audit Investigation Board AIM see Alternative Investment Market【UK】 AIMR see Association for Investment Management and Research AMCHAM see American Chamber of Commerce AMEX see American Stock Exchange AMS see Automatic Order Matching and Execution System AMS/2 see Automatic Order Matching and Execution System / Second Generation AMS/3 see Automatic Order Matching and Execution System / Third Generation ANNA see Association of National Numbering Agencies AOI see All Ordinaries Index AOSEF see Asian and Oceanian Stock Exchanges Federation APEC see Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation API see Application Programming Interface APRC see Asia Pacific Regional Committee of IOSCO ARM see adjustable rate mortgage ASAC see Asian Securities' Analysts Council ASC see Accounting Society of China 2 ASEAN see Association of South-East Asian Nations ASIC see Australian Securities and Investments Commission AST system see automated screen trading system ASX see Australian Stock Exchange ATI see Account Transfer Instruction ABF Hong -

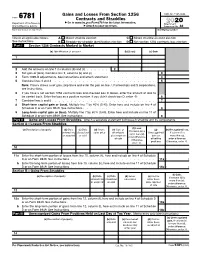

Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to for the Latest Information

Gains and Losses From Section 1256 OMB No. 1545-0644 Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form6781 for the latest information. 2020 Department of the Treasury Attachment Internal Revenue Service ▶ Attach to your tax return. Sequence No. 82 Name(s) shown on tax return Identifying number Check all applicable boxes. A Mixed straddle election C Mixed straddle account election See instructions. B Straddle-by-straddle identification election D Net section 1256 contracts loss election Part I Section 1256 Contracts Marked to Market (a) Identification of account (b) (Loss) (c) Gain 1 2 Add the amounts on line 1 in columns (b) and (c) . 2 ( ) 3 Net gain or (loss). Combine line 2, columns (b) and (c) . 3 4 Form 1099-B adjustments. See instructions and attach statement . 4 5 Combine lines 3 and 4 . 5 Note: If line 5 shows a net gain, skip line 6 and enter the gain on line 7. Partnerships and S corporations, see instructions. 6 If you have a net section 1256 contracts loss and checked box D above, enter the amount of loss to be carried back. Enter the loss as a positive number. If you didn’t check box D, enter -0- . 6 7 Combine lines 5 and 6 . 7 8 Short-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 40% (0.40). Enter here and include on line 4 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. See instructions . 8 9 Long-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 60% (0.60). Enter here and include on line 11 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. -

MAS362/MAS462/MAS6053 Financial Mathematics Problem Sheet 1

MAS362/MAS462/MAS6053 Financial Mathematics Problem Sheet 1 1. Consider a £100, 000 mortgage paying a fixed annual rate of 5% which is com- pounded monthly. What are the monthly repayments if the mortgage is to be repaid in 25 years? 2. You want to deposit your savings for a year and you have the choice of three accounts. The first pays 5% interest per annum, compounded yearly. The second pays 4.8% interest per annum, compounded twice a year. The third pays 4.9% interest per annum, compounded continuously. Which one should you choose? 3. Consider any traded asset whose value vT in T years is known with certainty. −rT Prove that the current value of the asset must be vT e where r is the continuously- compounded T -years interest rate. 4. A perpetual bond is a bond with no maturity, i.e., it pays a fixed payment at fixed intervals forever.1 Under the assumption of constant (continuously compounded) interest rates of 5%, what is the price of a perpetual bond with face value £100 paying annual coupon of 2.50% once a year and whose first coupon payment is due in three months? 5. The prices of zero coupon bonds with face value of £100 and maturity dates in 6, 12 and 18 months are £98, £96 and £93.5 respectively. The price of a 8% bond maturing in 2 years with semiannual coupons is £107. Use the bootstrap method to find the two-year discount factor and spot rates. 6. Consider the following zero-coupon bonds with face value of £100: Time to maturity Annual interest Bond price (in years) (in £) 0.5 0 97.8 1. -

How Did Too Big to Fail Become Such a Problem for Broker-Dealers?

How did Too Big to Fail become such a problem for broker-dealers? Speculation by Andy Atkeson March 2014 Proximate Cause • By 2008, Broker Dealers had big balance sheets • Historical experience with rapid contraction of broker dealer balance sheets and bank runs raised unpleasant memories for central bankers • No satisfactory legal or administrative procedure for “resolving” failed broker dealers • So the Fed wrestled with the question of whether broker dealers were too big to fail Why do Central Bankers care? • Historically, deposit taking “Banks” held three main assets • Non-financial commercial paper • Government securities • Demandable collateralized loans to broker-dealers • Much like money market mutual funds (MMMF’s) today • Many historical (pre-Fed) banking crises (runs) associated with sharp changes in the volume and interest rates on loans to broker dealers • Similar to what happened with MMMF’s after Lehman? • Much discussion of directions for central bank policy and regulation • New York Clearing House 1873 • National Monetary Commission 1910 • Pecora Hearings 1933 • Friedman and Schwartz 1963 Questions I want to consider • How would you fit Broker Dealers into the growth model? • What economic function do they perform in facilitating trade of securities and financing margin and short positions in securities? • What would such a theory say about the size of broker dealer value added and balance sheets? • What would be lost (socially) if we dramatically reduced broker dealer balance sheets by regulation? • Are broker-dealer liabilities