Glass Bangles of Al-Shihr, Hadramawt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writing Otherness: Uses of History and Mythology in Constructing Literary Representations of India’S Hijras

Writing Otherness: Uses of History and Mythology in Constructing Literary Representations of India’s Hijras A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Sarah E. Newport School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Table of Contents Abstract…………….……………………………………………………………………………………………… 3 Declaration……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Copyright Statement..………………………………………………………………………………………... 4 Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………………………... 5 Introduction: Mapping Identity: Constructing and (Re)Presenting Hijras Across Contexts………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 7 Chapter One: Hijras in Hindu Mythology and its Retellings……………………………….. 41 1. Hijras in Hindu Mythology and its Interpretations…………….……………….….. 41 2. Hindu Mythology and Hijras in Literary Representations……………….……… 53 3. Conclusion.………………………………………………………………………………...………... 97 Chapter Two: Slavery, Sexuality and Subjectivity: Literary Representations of Social Liminality Through Hijras and Eunuchs………………………………………………..... 99 1. Love, Lust and Lack: Interrogating Masculinity Through Third-Gender Identities in Habibi………………………………………..………………. 113 2. The Break Down of Privilege: Sexual Violence as Reform in The Impressionist….……………...……………………………………………………….……...… 124 3. Meeting the Other: Negotiating Hijra and Cisgender Interactions in Delhi: A Novel……...……………………………………………………..……………………….. 133 4. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………. 139 Chapter Three: Empires of the Mind: The Impact of -

Gowri Dissertation Draft 5.10.16

Viral Politics: Sex Worker Activism and HIV/AIDS Programs from Bangalore to Nairobi By Srigowri Vijayakumar A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Raka Ray, Chair Professor Peter B. Evans Professor Gillian P. Hart Professor Lawrence Cohen Spring 2016 Abstract Viral Politics: Sex Worker Activism and HIV/AIDS Programs from Bangalore to Nairobi By Srigowri Vijayakumar Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Raka Ray, Chair This dissertation studies the international success story of India’s HIV/AIDS response and the activism of sex workers and sexual minorities that produced it. A number of recent ethnographies have turned their attention to the workings of state programs in middle-income countries (e.g. Baiocchi 2005; Sharma 2008; A. Gupta 2012; Auyero 2012), demonstrating both the micro-effects of state strategies for managing poverty on poor people and the ways in which state programs are produced outside the visible boundaries of “the state”—through NGOs and social movement organizations as well as transnational donors and research institutes. Yet, even as state programs are constituted through struggles over resources and representations within and outside the official agencies of the state, states also derive legitimacy from projecting themselves as cohesive rather than disaggregated, and as autonomous from society rather -

Construction of the Hijra Identity a Thesis Presented by Syeda S. Shawkat ID: 16217005 to the Department of Economics and Social

Construction of the Hijra Identity A thesis presented by Syeda S. Shawkat ID: 16217005 To The Department of Economics and Social Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree with honors of Bachelor of Social Science in BRAC University [December, 2016] Glossary i. Maigga – Slang term for a heterosexual man who does not follow the dictated performance for his gender. ii. Guruma– The leader of the Hijra community in a given locality. The Hijra who is considered as the mother of everyone in that community. iii. Chela – The Hijra directly under the guruma/ subordinate. The person is considered the daughter of the guruma. iv. Nati – The Hijra under the chela. The person is considered the granddaughter of the guruma. v. Dhol – A double headed drum. vi. Gamcha - Is a thin, coarse, traditional cotton towel that is used to dry the body after bathing. vii. Laddoo – Type of ball- shaped sweets popular in Indian Subcontinent. viii. Gaye holud – Translates to turmeric on the body” is a Bangladeshi wedding ceremony. ix. Achol/ aanchal - means the end of a saree, the traditional Bangladeshi and Indian dress for women. x. Bharatnatyam – It is a form of Indian classical dance. It is a solo dance that was exclusively performed by women. xi. UNDP – United Nations Development Programme. xii. SSSHS – ShochetonShomaj Sheba Hijra Shongoton. xiii. Bondhu -Bondhu Social Welfare Society. Table of Contents 1. Abstract ........................................................................................................4 2. Acknowledgment .........................................................................................5 3. Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................6 4. Chapter 2: Methodology ...........................................................................11 5. Chapter 3: Childhood – Gender Struggle and the emergence of psycho- social identity ............................................................................................15 6. -

Download Lookbook 1

HANNAH WARNER JEWELLERY DESIGNER COLLECTION HANNAH WARNER Since the launch of her Debut collection in Autumn 2009, Hannah Warner is fast becoming one of the most talked about, up and coming jewellery designers of a new generation. Initially based in London, where she studied at Wimbledon School of Art and later at London Metropolitan, Hannah then moved to New York, continuing her studies at the prestigious Gemological Institute of America. Hannah now lives between these two spirited cities, drawing on her surroundings as a direct inspiration to her work. “I take a great deal of influence from everything around me in day to day life and also from different cultures, be it the rigidity of man-made structures, architecture, city life or something more organic, natural, evolving.” Hannah is a passionate traveler and this is evident within her work both stylistically and in the precious stones she uses, many of which are hand sourced from India and the far east. Hannah Warner’s escalating success and reputation within the industry is generating considerable interest from both fashion insiders and celebrity clients alike. She is currently working on her next collection as well as various fashion and art collaborations and commissions. G O L D B R A C E L E T COLLECTIONS: CORAL / SKULL & BONES / EGYPTIAN CORAL G O L D B R A C E L E T STARF ISH EARRINGS CORAL BRACELET CHAIN TO RING NUGGET EARRINGS TANZ ANITE CRATER CORAL NECKLACE C LOCKWISE FROM TOP LEF T ; TWIG CORAL NECKLACE, AMBER NUGGET CORAL NECKLACE HALF CONE EARRINGS, STAR & HORN ANKLET, -

Homebased Workers of Bangle Industry

A B a s e l i n e S u r ve y o n Homebased Workers of Bangle Industry HomeNet Pakistan Labor Education Foundation (LEF) Karachi This document is an output form a project funded by HomeNet South Asia Contents Acknowledgement 5 Acronym 7 1. Introduction of HomeNet Pakistan 9 2. Background of Baseline Survey of the Bangle Workers 13 3. Procedure of bangle Making 21 4. Analysis: Condition of the Bangle Workers 31 5. Laws 43 6. Recommendations 53 7. Case studies 57 Annexes 65 Acknowledgement HomeNet Pakistan would like to extend its gratitude to Labour Education Foundation Karachi for conducting the survey on homebased workers of the Bangle Industry, Hyderabad. The survey was conducted by the dedicated team work of home based women workers cooperative members, their association and Labour Education Foundation’s staff in Hyderabad and Karachi. The report is based on HBWWs interviews of different processing sectors of bangle industry in Hyderabad. The team led by Miss Zehra Akber Khan under the guidance of Mr Nasir Aziz, conducted the survey and compiled the facts and figures for the report. The survey was carried in July –September 2009 and successfully accomplished by the ten members’ fieldwork team of enthusiastic interviewers led by Ms. Irfana Jabbar. HNP is especially grateful to Home Based Women Workers Centers’ Association (HBWCA) for providing valuable contacts as well as logistical support, and for facilitating interviews in ten different areas of Hyderabad. The facilitation provided by the Women Study Center, Karachi University in documenting the report is highly commendable. LEF team deserves appreciation for data processing, tabulation, translation and over all conducting the survey on the homebased workers of Bangle Industry, Hyderabad. -

Wax Insignia Hand Cast in Italy

Wax Insignia Hand Cast in Italy Tel: Tel: 877.591.4464 Distributed Exclusively by Freund by Exclusively Distributed Fax: 239.592.6254 - Mayer & Co. Inc. P.O Box 112469, Naples FL 34108 Naples 112469, Box P.O Co. Inc. & Mayer 2011 [email protected] www.WaxInsignia.com . Great. .Looks. Dear Valued Retail Partner: We are proud to introduce you to our 2011 Collection of Wax Insignia Jewelry. Our pieces are casual treasures inspired by history and the people around us, or sophisticated accents of fashion forward jewelry that evoke passionate responses from old and new fans alike. We offer many complementing products that allow for a mix n’ match look to suit anyone’s style. Wearable, Giftable Meaningful Jewelry for All Index Pages 4-5………… Square Vintage Style Pendants & more Pages 6-7………………Round Cerif Initial Pendants & more Pages 8-9…………….Petite Designs & Horoscope Pendants Pages 10-11...…………………………………..Mini Accent Charms Pages 12-13..………………………….Regal Pendants and Rings Pages 14-15………………..Round Charms and Key Pendants Pages 16-17……………………….….Chains, Pearls & Bracelets Pages 18-19…………………….Retailer Displays & Packaging 2 Page 2 . About Wax. Insignia. Jewelry. Benefits of carrying Wax Insignia Jewelry in your store: Artisan Jewelry Handcrafted In Italy at excellent retail price points Free-formed Wax Seal Shapes with raised relief imprints Made from mixed metals with a hand applied antique finish for long wear and durability-no oxi- dization. Made by talented Artisans in the foothills of Florence, Italy. All Jewelry nickel free & lead free Fast shipping –Low Minimums Our Inspiration Our Jewelry was created to pay homage to the noble, romantic and enchanting tradition of sealing letters with wax seals. -

Ethnographical Views on Valaikappu. a Pregnancy Rite in Tamil Nadu Pascale Hancart Petitet, Pragathi Vellore

Ethnographical views on valaikappu. A pregnancy rite in Tamil Nadu Pascale Hancart Petitet, Pragathi Vellore To cite this version: Pascale Hancart Petitet, Pragathi Vellore. Ethnographical views on valaikappu. A pregnancy rite in Tamil Nadu. Indian Anthropologist, 2007, 37 (1), pp.117-145. hal-00347168 HAL Id: hal-00347168 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00347168 Submitted on 15 Dec 2008 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Pascale Hancart Petitet (CReCSS, Aix) & Vellore Pagathi (PILC, Pondichery) Ethnographical views on valaikāppu. A pregnancy rite in Tamil Nadu In Indian Anthropologist. Special Issue on the Ethnography of Healing 37(1). 2007. Guest Editor: Laurent Pordié Ethnographical views on the valaikāppu. A pregnancy rite in Tamil Nadu Pascale Hancart Petitet* and Vellore Pragathi** * Pascale Hancart Petitet is an anthropologist, member of the Centre de Recherche Cultures, Santé, Sociétés (CReCSS), Paul Cézanne University at Aix-Marseille, and affiliated to the French Institute of Pondicherry (IFP). ** Vellore Pragathi is an anthropologist, lecturer at the Pondicherry Institute of Linguistic and Culture (PILC) and affiliated to the French Institute of Pondicherry (IFP) Abstract In Tamil Nadu, the end of the first pregnancy is marked by the celebration of the valaikāppu rite. -

Dealer Catalog Fall + Winter 2014

DEALER CATALOG FALL + WINTER 2014 WAXING POETIC | FALL + WINTER 2014 TABLE of CONTENTS WHO WE ARE 2 PRODUCT INFORMATION 5 CATALOG OF PRODUCTS Charms & Pendants…8, Inspiration…48, Chains…52, Bracelets…60, Necklaces…70, Rings…80 8 INDEX 82 REPS 84 1 WHO WE ARE ABOUT WAXING POETIC Waxing Poetic celebrates the potential for transformation in all of us. Our jewelry pays homage to the journey of our lives: where we come from, what our stories are, and how they have influenced both the world and us. THE MEANING BEHIND THE NAME The name Waxing Poetic embodies life’s voyage. While the words ‘waxing poetic’ mean ‘speaking in a flowery or poetic fashion,’ we look at the individual words and are reminded that ‘waxing’ means ‘to become, to evolve into something else’ and ‘poetic’ means… just that, and everything related. GROWING UP PagLIEI: EVER-TIED SISTERS Patti and Lizanne are the two youngest daughters of a boisterous, close-knit Italian- American family from the Philadelphia/New Jersey area. Their childhood home was an environment rich with love, faith, iconography, and storytelling, where myths and fables played as much of a part in their development as morals and a quest for meaning. Patti and Lizanne were blessed with a tremendously supportive mother, Rita, who encouraged her girls to be tenacious and take risks, while also stressing the importance of keeping faith: in themselves, in each other, in love, and in possibilities. They took different paths when they left home, but their hearts were tied. 2 ABOUT OUR FOUNDER: During this vibrant period, she apprenticed with PATTI PAGLIEI-SIMPSON various artists and designers, and soon began a long stint designing sets for music videos and film, While honing skills as a painter to achieve her BFA which led to story editing, producing, and then, at Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers building and designing websites for a gleaming new University, Patti also fell in love with several phenomenon known as the internet. -

Celtic Ankle Bracelets Pdf Free Download

CELTIC ANKLE BRACELETS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marty Noble | 2 pages | 01 Nov 2000 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486412948 | English | New York, United States Celtic Ankle Bracelets PDF Book However, there are rumors that wearing an ankle bracelet on the left ankle signifies that a woman is in an open relationship. James Kilgore runs a project called Challenging E-Carceration that opposes the use of electronic monitors. Luke J. I appreciate the work you've done for me. In stock. If you want to send gifts directly to the recipient, please let us know if you'd like us to include a gift note so no prices are shown, and we can also remove branding from the packaging if required. All of our orders are sent by 1st Class Royal Mail, and should arrive within days once dispatched. While there are few hard and fast ankle bracelet rules, there are some things to consider when wearing an ankle bracelet. Joseph Bennett sits for a photo in Roxbury, Mass, on July 30, Shield of Faith Woven Bracelet Silvertone. Labriola suffered from a myriad of debilitating illnesses and relied on an oxygen tank to breathe. Deliveries are made by Royal Mail and may require a signature on arrival, so please keep this in mind when specifying your delivery address, eg. Since then, the use of electronic monitors to track accused and convicted offenders has spread across the United States. Crafted from fine metals like white bronze and sterling silver, our Celtic anklets possess a bright gleam that makes each one a work of art. -

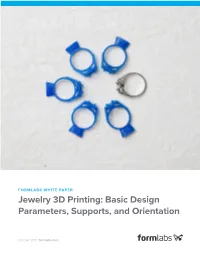

Jewelry 3D Printing: Basic Design Parameters, Supports, and Orientation

FORMLABS WHITE PAPER: Jewelry 3D Printing: Basic Design Parameters, Supports, and Orientation October 2017 | formlabs.com Table of Contents Introduction 3 Mechanics of Printing 4 Basics of Digital Design for Printing and Casting 6 Orientation and Supports 18 Conclusion 23 FORMLABS WHITE PAPER: Jewelry 3D Printing: Basic Design Parameters, Supports and Orientation 2 Introduction In order to best understand the techniques and parameters for developing a digital design for 3D printing, it is important to understand how your Form 2 desktop stereolithography 3D printer works In addition to the process of hardening and building up very thin layers of resin with a laser, the layers undergo shear forces during printing as the printer resets and prepares each subsequent layer Understanding the forces involved during printing aids in understanding parameters for both design and print preparation This paper presumes a working knowledge of a CAD modeling program with files that can be converted to STL or OBJ format We used Rhino5, but the same principles apply to any CAD software that you are comfortable with The models shown as examples make no claim to aesthetic value, but were created to demonstrate the principles described Another technical process, casting, should also influence the way the model is designed Just because you are able to print a model on your Form 2 does not mean that it will cast successfully FORMLABS WHITE PAPER: Jewelry 3D Printing: Basic Design Parameters, Supports and Orientation 3 Mechanics of 3D Printing OVERVIEW Prints -

ANUJA TOLIA JEWELRY Contact: [email protected] P: 248.330.5933 W

act ANUJA TOLIA JEWELRY Contact: [email protected] P: 248.330.5933 W: www.anujatolia.com IG: anujatoliajewelry act Bonita Ring 700R21- $16 Medley Ring Track Ring 331R57- $25 355R8- $26 Connect 4 Ring 355R4- $16 Gadget Ring 543R85- $16 Oyster Ring 657R1- $19 Angie Pave Band 522R3- $28 Jolie Stackable Ring 552R4- $25 Pearl Drip Ring Carousel Ring 657R2- $19 521R1- $20 Gem Ring Foundation Ring Emerald City Ring 229R13- $21 TM024871- $29 700R16- $28 Ellish Stackable Ring Space Ring TM044794- $13 each TM028954- $23 Jungle Ring TM046652- $30 Deco Ring Trance Color Ring TR3093- $46 SubMarine Color Ring TM046553- $33 TM034796- $15 Crochet Stackable Ring 500R3- $25 (each) Eternity Ring Jenga Ring 678R2- $24 322R7- $25 Loop D’ Loop Ring 331R32- $23 Diva Stackable Ring 2 Feather Ring LR1549- $65 TM025653- $29 Ice Stackable Ring R0784- $29 per set Snake Ring BGR01106- $17 Geo Stone Ring Curly Ring Ombre Ring TM028715- $33 TM048279- $44 TM046555- $20 Pave Square Stackable Ring Baguette Stackable Ring TM047328- $18 each TM023615- $23 Marquette V Ring 5 Crown Ring TM028570- $19 TM036528- $25 (also coMes in silver) Tear Drop Stackable Ring Dagger Ring TM026988- $19 4 Dice Ring RNG-020- $21 TM035105- $45 Wave Ring RailWay Ring 83701- $9 Sunrise Ring Lucy Ring CR00794- $23 83740- $14 83796- $26 Tiara Finger Ring TM022303- $36 3 Flower Finger Piece TM022453- $43 CroWn Finger Piece TM022441- $36 OrigaMi Hand Bracelet SLV-012- $19 Dua Hand Bracelet Peacock Hand Piece TM035080- $20 TM022465- $50 BlooM Hand Piece TM023818- $40 act Destiny Hoop 543E4- $33 -

Collection #12 Winter 2020 Jungle

COLLECTION #12 WINTER 2020 JUNGLE BRACELETS BANGLES JEWELLERY RINGS EARRINGS NECKLACES ORNEMENTS BRAND WHO ARE WE ? Based in Paris, Bangle up is a French modern jewellery brand with a distinctive and unique signature look: enamel bracelets lined with fine gold and decorated with pop colors and custom graphic prints. Our collections are inspired by our founders’ many travels around the world with a desire to pay tribute to women everywhere: our designs always try to link a free spirited, nomadic way of life with classic Parisian chic. Our bracelets can be worn individually to complete your look with a subtle splash of color or accumulated around your wrists for a maxi effect: in any case, they can be mixed and matched to create your own personal look. THE ART OF TRADITIONAL WORKMANSHIP Each bangle up jewellery is fabricated in coloured enamel and soaked in a gold bath by our partners in Asia. We select them with lots of requirements so that they share our savoir-faire, our values and our ethic. Our bangles, cuffs, bracelets, earrings and rings all follow the same workmanship process during 5 hours before coming back to the Parisian workshop. Coloured or enamel-printed, they are placed in an oven, hardened, plated and varnished so that they do not darken and keep their brightness for years. The whole team, like the bangle lovers, constantly wait for these little marvels – yet so affordable – with lots of eagerness! 1 OUR STORY Bangle up was founded in 2014 by duo Danielle and Kevin. After working for 15 years for internationally renowned French lingerie brand, Princesse tam tam, Danielle was dreaming of launching her own entrepreneurial and creative project.