Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 20 June 2019] P4438b

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Three, Four, Five Civil Liberties Groups Emerge in WA

Chapter 8 – Western Australia Three, four, five civil liberties groups emerge in WA The first mention of a civil liberties body in Perth came in an article in a local daily newspaper in September 1936: “The establishment of a Council of Civil Liberties in Perth was advocated yesterday by Mr. C. Bader (sic), readers’ counsellor under the adult education scheme of the University of Western Australia. Mr. Badger made the suggestion when discussing the action of the Customs Department in seizing 17 books from the Perth Literary Institute last week. “In view of the general tendency to interfere with the free circulation of books, and especially the tendency of the Federal Government to devolve its powers to irresponsible departments, said Mr. Badger, one felt there was a great need for a body in Perth affiliated to or parallel with the Council of Civil Liberties in Melbourne. This council, in its own way, was a development of the Council for Civil Liberties in England, whose president was Mr. E. W. Forster, the author of ‘Passage to India’. “It was a saddening fact that the battle for liberty, which people were apt to regard as having been won for them by their ancestors, had to be fought anew in each generation. “Despite the ample powers which governments had to suppress overt sedition and treachery, continued Mr. Badger, democratic governments still found it necessary to pass Acts like the Crimes Act, which were contrary to the whole tradition of British law and justice.” 1 Badger (photo), then just starting his career, went on to become the first Director of the Council of Adult Education in Victoria, a position he held until 1971. -

Estelle Blackburn

Estelle Blackburn Speaker, Author, Walkley Award winning journalist Estelle Blackburn took on the justice system and, against all odds, rectified two grave injustices, demonstrating the power of an individual to alter history and improve society at a fundamental level. Now based in Canberra, Estelle is a former Perth journalist who has worked for The West Australian and the ABC, various W.A. Government ministers and a Premier. She gave up full-time work and spent six years researching and writing the book Broken Lives, published in 1998. Estelle’s book exposed an injustice which led to the 2002 and 2005 exonerations of John Button and Darryl Beamish, who had been convicted of murder in the 1960s, and created history as the longest standing convictions to be overturned in Australia. Her unfunded, determined sleuthing unearthed fresh evidence that prompted the Attorney General to allow the men new appeals after they had lost a combined total of seven Appeals in the 60s. Coming across the story by chance and persisting with it turned Estelle’s life around. Here was a courageous woman who without a second thought impoverished herself to fight the cause for strangers. With no legal training and armed only with extraordinary qualities of courage and determination, she took on the system and won. Because of her vision, hard work and self-sacrifice the justice system may have been set on a truer course. This work won her an Order of Australia medal in the 2002 Queens Birthday Honours List for her service to the community through investigative journalism. She has also won journalism’s highest honour, a Walkley Award for the Most Outstanding Contribution to Journalism, the Perth Press Club Award, Western Australia’s Clarion Award, the Premier’s Award for non-fiction, the Australian Crime Writers’ Award for best true crime, and a scholarship to undertake a PhD in journalism at Murdoch University. -

Electronic Document

GriffithREVIEW47.indb 1 21/01/2015 3:43 pm Praise for Griffith Review ‘Essential reading for each and every one of us.’ Readings ‘A varied, impressive and international cast of authors.’ The Australian ‘Griffith Review is a must-read for anyone with even a passing interest in current affairs, politics, literature and journalism. The timely, engaging writing lavishly justifies the Brisbane-based publication’s reputation as Australia’s best example of its genre.’ The West Australian ‘There is a consistently high standard of writing: all of it well crafted or well argued or well informed, as befits the various genres.’ Sydney Review of Books ‘This quarterly magazine is a reminder of the breadth and talent of Australian writers. Verdict: literary treat.’ Herald Sun ‘Griffith Review editor Julianne Schultz is the ultra-marathoner of Australian cultural life.’ Canberra Times ‘At a time when long form journalism is under threat and the voices in our public debate are often off-puttingly condescending, hectoring and discordant, Griffith Review is the elegant alternative.’ Booktopia Buzz ‘Griffith Review is a consistently good journal. There is some terrific writing on display as well as variety and depth to the issues being grappled with.’ The Age ‘Australia’s most important literary essay magazine.’ Courier-Mail ‘At once comfortable and thought-provoking, edgy and familiar, [it] will draw the reader through its pages.’ Australian Book Review ‘Griffith Review is a wonderful journal. It’s pretty much setting the agenda in Australia and fighting way above its weight… You’re mad if you don’t subscribe.’ Phillip Adams ‘Once again, Griffith Review has produced a stunning volume of excellent work. -

Chap 8 WEST AUST CCL 200514 Proofed

Chapter 8 – Western Australia Three, four, five civil liberties groups emerge in WA The first mention of a civil liberties body in Perth came in an article in a local daily newspaper in September 1936: “The establishment of a Council of Civil Liberties in Perth was advocated yesterday by Mr. C. Bader (sic), readers’ counsellor under the adult education scheme of the University of Western Australia. Mr. Badger made the suggestion when discussing the action of the Customs Department in seizing 17 books from the Perth Literary Institute last week. “In view of the general tendency to interfere with the free circulation of books, and especially the tendency of the Federal Government to devolve its powers to irresponsible departments, said Mr. Badger, one felt there was a great need for a body in Perth affiliated to or parallel with the Council of Civil Liberties in Melbourne. This council, in its own way, was a development of the Council for Civil Liberties in England, whose president was Mr. E. W. Forster, the author of ‘Passage to India’. “It was a saddening fact that the battle for liberty, which people were apt to regard as having been won for them by their ancestors, had to be fought anew in each generation. “Despite the ample powers which governments had to suppress overt sedition and treachery, continued Mr. Badger, democratic governments still found it necessary to pass Acts like the Crimes Act, which were contrary to the whole tradition of British law and justice.” 1 Badger (photo), then just starting his career, went on to become the first Director of the Council of Adult Education in Victoria, a position he held until 1971. -

![[Tuesday, 10 November 1998] 2973 Using the System on December 31](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1420/tuesday-10-november-1998-2973-using-the-system-on-december-31-5351420.webp)

[Tuesday, 10 November 1998] 2973 Using the System on December 31

[Tuesday, 10 November 1998] 2973 using the system on December 31 1998 to coincide with amendments to the Public Sector Management (Review Procedures) Regulations 1995. Similar errors therefore should not occur in future. I have advised the relevant Ministers. The letter is signed, "Don Saunders, Commissioner for Public Sector Standards, November 4, 1998". [See paper No 339.] SELECT COMMITTEE ON NATIVE TITLE RIGHTS IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA Final Report, Tabling Hon Tom Stephens (Leader of the Opposition) presented the final report of the Select Committee on Native Title Rights in Western Australia, and on his motion it was resolved - That the report do lie upon the Table and be printed. [See paper No 384.] Papers, Tabling HON TOM STEPHENS (Mining and Pastoral - Leader of the Opposition) [3.44 pm]: I seek leave to table papers of the Select Committee on Native Title Rights in Western Australia. By way of explanation to you, Mr President, and through you to the Leader of the Government, he will be familiar with this seeking of leave because he sought similar leave in similar circumstances for a committee that did some overseas work on an unrelated issue. Hon N.F. Moore: You do not have to talk me into it. Hon TOM STEPHENS: Okay. I have here a substantial number of documents which I hope the House will see fit to allow to lie on the Table of the House so that they may be accessed by the public. The committee has been particularly privileged in the work it undertook. The Select Committee on Native Title Rights in Western Australia has also directed me to present papers which the committee collected on its trip to Canada during July of this year. -

Tom Percy QC: Correcting History

FLINDERS SYMPOSIUM ON MISCARRIAGES OF JUSTICE 7 – 8 NOVEMBER 2014 CORRECTING HISTORY THE BUTTON AND BEAMISH CASES Introduction I once supported the death penalty. It had a fundamental righteousness about it, an eye-for-an-eye type of justice, with a superficial but immediate appeal to it. A fortuitous sequence of events was however to change my mind as I came to close quarters with two men and a woman who had each experienced the shadow of the gallows. Even though we haven’t hanged anyone in Australia since 1967, and in WA since 1964, those unlucky enough to be convicted of wilful murder in Perth were still sentenced to death until 1984, when the mandatory penalty was removed from the Criminal Code. The last one of those was a country woman named Brenda Hodge, who was convicted of the shooting of her abusive de facto husband in my home town of Kalgoorlie in 1984. She was my client and I was junior (very junior) counsel to Henry Wallwork QC at her trial. We all believed that she wouldn’t hang, but watching on as a Mr Justice Pidgeon pronounced the litany of the death sentence was something I shall never forget. It was a galling experience; like something out of a movie, but it was real, and had the full force of the law. Technically she was a dead woman walking. The terror in her eyes as the sentence was passed, and sitting with her in the cell afterwards, will haunt me forever. I had started to reassess my views on the death penalty. -

26 November 1992

7338 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thursday, 26 November 1992 THE SPEAKER (Mr Michael Barnett) took the Chair at 10.00 am, and read prayers. PETITION - BICYCLE HELMETS LEGISLATION OPPOSITION MR KIERATH (Riverton) [10.01 am]: I present the following petition - To: The Honourable the Speaker and members of the Legislative Assembly of the Parliament of Western Australia in Parliament assembled. We, the undersigned, protest strongly against the recent introduction of compulsory helmets for adult bicycle riders. This law is an unjustified restriction of our freedom, has no clear statistical justification, and is a cheap substitute for real improvement in traffic conditions, for cyclists and motorists alike. Your petitioners therefore humbly pray that you will give this matter earnest consideration and your petitioners, as in duty bound, will ever pray. The petition bears 12 234 signatures and I certify that it conforms to the Standing Orders of the Legislative Assembly. The SPEAKER: I direct that the petition be brought to the Table of the House. [See petition No 140.] STAMP AMENDMENT BILL Introduction and First Reading Bill introduced, on motion by Dr Lawrence (Treasurer), and read a first time. Second Reading DR LAWRENCE (Glendalough - Treasurer) [10.03 am]: I move - That the Bill be now read a second time. The purpose of the Bill is to exempt from stamp duty the standard form proprietor/resident nursing home agreements which are being introduced by the Federal Government to promote and protect the rights of nursing home residents. The Western Australian Government supports this initiative. The standard form agreement will apply in more than 90 approved non-Government nursing homes - those covered by the National Health Act 1953 - in Western Australia. -

Imagereal Capture

JAN 19991 BOOK REVIEWS Who Killed Rosemary Anderson? By Estelle Blackburn (Stellar Publishing Pty Ltd 1998 pp 410 $24.95) ESPITE its status as the capital city of Western Australia, Perth in the year D 1960 was much more akin to a large country town than a bustling metropolis. Even today long-term residents reminisce about the 'good old days' when people could leave their houses unlocked, sleep on front verandahs on hot summer nights and walk the streets without fear. But in the early 1960s all this was to change. This book begins by chronicling the life and crimes of Eric Edgar Cooke. During the period 1958 to 1963, Cooke was, on his own admission, responsible for causing the deaths of five Perth residents, causing serious injury to nearly a dozen others and committing innumerable burglaries and car thefts. Ultimately Cooke found a place in Western Australian history as the last person to die on the gallows of Fremantle gaol. But this book is not just a chronicle of Cooke's activities. Before he was apprehended, two men were charged and convicted of offences to which Cooke later confessed. The first and perhaps better known of these was a hearing and speech impaired youth named Darryl Raymond Beamish who was sentenced to death (later commuted to life imprisonment) for the wilful murder of Jillian Brewer in 1959. Subsequent to his apprehension in 1963, Cooke confessed to this murder, and declared that Beamish was innocent. As a result the then Minister of Justice referred Beamish's conviction to the Court of Criminal Appeal; however, after hearing evidence from Cooke, the court concluded that there were no grounds to set aside the conviction and dismissed the appeal. -

Essay Sir Ronald Wilson: an Appreciation

ESSAY SIR RONALD WILSON: AN APPRECIATION ROBERT NICHOLSON AO∗ [Sir Ronald Wilson (known by his own wish to all as Ron Wilson) was short in stature and long in energy. He was a person who devoted himself passionately to all causes in which he believed. Most of these were derived from or constituted by his religious faith and found expression in relation to the law. From humble beginnings to the highest judicial office, he preserved his own unique humanity and contact with people. This is a story of his life in the law and beyond.] CONTENTS I Beginnings .............................................................................................................. 499 A Legal Education......................................................................................... 500 B Family Life................................................................................................. 501 C Religious Belief.......................................................................................... 501 D Professional Practice.................................................................................. 502 E Solicitor-Generalship ................................................................................. 503 F Constitutional Predictions.......................................................................... 504 II High Court of Australia — 1979–89 ...................................................................... 507 A Constitutional Decision-Making................................................................ 508 B Criminal -

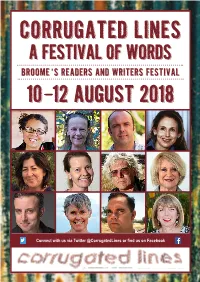

Connect with Us Via Twitter @Corrugatedlines Or Find Us on Facebook Write a Limerick Competition – Theme: the Colour Red FREE ONLINE EVENT Entries in by 3Rd August

Connect with us via Twitter @CorrugatedLines or find us on Facebook Write a Limerick competition – Theme: The Colour Red FREE ONLINE EVENT Entries in by 3rd August Write and submit one original Limerick on the theme The Colour Red to the Backroom Press Facebook page before the closing date. Winning entries announced and read at Word of Mouth on Saturday night, August 11. For guidelines on writing a Limerick, see the Backroom Press Facebook page. Non-users of Facebook may submit by email to [email protected] PRE-FEST Yawuru Haiku BOOKINGS REQUIRED 4–5.30pm Nyamba Buru Yawuru – 55 Reid Road, Cable Beach Join the Mabu Yawuru Ngan-ga language team and create short Japanese-style haiku poems. Using Yawuru words, this traditional poetic form will give expression to our country and seasons, and introduce you to some Yawuru language. Max 12 participants. Bookings with [email protected] Landscape writing with Donna Marie Carman FREE EVENT 4.30–5.30pm Gallery Sobrane – 48 Carnarvon Street (next door to Matso’s) Landscape Snapshot: Personal responses of the beholder. Create prose, poetry or a single word to represent your experience of landscape in light of guided imagery and ideas. Perspectives of Broome landscapes will be explored through written word during this workshop as part of Donna’s ten-day Artist Residency at Gallery Sobrane in August. Prologue FREE EVENT 6.30–7.30pm Broome Public Library – Corner Hamersley and Haas Streets Join us for the opening of Corrugated Lines 2018. Be welcomed by the Traditional Owners of Yawuru country and listen to some Yawuru songs performed by the Walalanga Ngan-ga singers. -

Three Accounts of Eric Edgar Cooke's Murderous Reign

The town becomes a city: three accounts of Eric Edgar Cooke’s murderous reign Paul Genoni School of Media, Culture and Creative Arts Curtin University The town becomes a city: three accounts of Eric Edgar Cooke’s murderous reign Eric Edgar Cooke is remembered as Perth’s, and Western Australia’s, most notorious serial killer. From the mid-1950s Cooke engaged in a prolonged series of break-ins, thefts, violent attacks and eventually murders that ended only with his arrest in August 1963. In this time he was responsible for causing serious physical injury to over 20 people, many in their own homes, and eight were killed. Cooke was an opportunist murderer. Unlike most serial killers he had no obvious modus operandi— his murders including the running down of a pedestrian; a stabbing; a bludgeoning with a hatchet; a strangulation, and four shootings. It was because of this bizarre aspect of his crimes that police and the public took some time to realise they had a serial killer in their midst. Many of Cooke’s crimes occurred in Perth’s well-to-do western suburbs, and in his most notorious outrage he went on a shooting spree in the beachside suburb of Cottesloe and riverside Nedlands in the early hours of January 27th 1963. In a series of four incidents, unrelated except for Cooke’s involvement, five people were shot and three killed. It was at this point that the killer was dubbed ‘The Nedlands Monster’ and Perth went into a state of shock and fear. Not only are the Cooke murders infamous because of their scale and oddity, but for other reasons they have lingered in the memory of West Australians. -

A Public Lecture

Networked Knowledge Media Reports Networked Knowledge Western Australia Media Reports This page set up by Dr Robert N Moles [Underlining, where it occurs, is for NetK editorial emphasis] University of Western Australia – Lumina Public Lecture Challenging justice – changing lives - A public lecture by Estelle Blackburn OAM It is generally agreed that 1% of the prison population are innocent inmates who are the victims of injustice. This presentation will detail two wrongful convictions in 1961 and 1963 and how a Perth journalist with no legal training could succeed in gaining the innocent men’s exonerations 40 years later, winning against the odds after they had lost seven combined appeals in the 60s. When John Button’s manslaughter conviction was quashed by the WA Court of Criminal Appeal in 2002, and Darryl Beamish’s wilful murder conviction was quashed in 2005, they were the longest standing convictions to be overturned in Australia. As well as the exonerations, the work corrected Perth’s history. Eric Edgar Cooke, the perpetrator of the two murders and the last person executed in WA, had been remembered for killing six people and attempting to kill two more in 1963. Cooke is now recognised for eight murders and 14 attempted murders over a five-year period from 1958. The work also gave a voice to 12 of Cooke’s previously-unknown attempted murder victims, gave hope to innocent prisoners and raised public awareness of wrongful conviction and its causes: police misconduct including blinkered investigation, over-zealous prosecutors, weak legal representation for the uneducated and marginalised, false confessions, fabricated evidence by witnesses with incentives, faults in forensics, eyewitness misidentification and fallible memory.