Impression Products, Inc. V. Lexmark Int'l, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GENESIS S816 Print

3-Year WIRELESS - N WARRANTY5 3 SECOND SCAN1 PREMIUM PHOTO TOUCH SCREEN QUALITY GENESIS S816 Print. Copy. Scan. Fax. Web. BUILT FOR SPEED Lexmark GENESIS Wireless 4-in-1 for Home Oces S816 Printing With Flash Scan, go from 1 page document to digital in as PRINT TECHNOLOGY Thermal Inkjet little as 3 seconds. Flash Scan allows you to quickly and easily COLOR TECHNOLOGY 4 Color Inkjet - Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black PRINT RESOLUTION, BLACK Up to 2400 x 1200 dpi scan multiple images to upload and share. The digital camera PRINT RESOLUTION, COLOR Up to 4800 x 1200 dpi technology also provides an Instant Preview so you can make (1) MAXIMUM PRINT SPEED (DRAFT, BLACK): UP TO 33 ppm sure your scans and copies turn out the way you expected MAXIMUM PRINT SPEED (DRAFT, COLOR): UP TO 30 ppm MAXIMUM MONTHLY DUTY CYCLE: UP TO 3000 pages per month FEATURES & BENEFITS pages a device could deliver in a month using a multishift operation. This metric provides a comparison of robustness in relation to other 4.3” web-connected touch screen allows you to create Lexmark printers and MFPs. customized 1-touch SmartSolutions to simplify common tasks, PRINT NOISE LEVEL, OPERATING 50 dBA such as scan to email. Also, get the news, view your favorite Copying photo sharing sites and discover the weather - directly from MAXIMUM COPY SPEED (DRAFT, BLACK): UP TO 25 cpm your printer. Whatever you need, there’s a SmartSolution. MAXIMUM COPY SPEED (DRAFT, COLOR): UP TO 21 cpm REDUCE / ENLARGE RANGE 25 - 400 % Print from multiple computers located virtually anywhere in COPY NOISE LEVEL, OPERATING 50 dBA Scanning with 802.11n (2). -

Trade-In Promotions Eligibility List Trade-In Promotions Eligibility List

Xerox Trade-In Program Eligibility List Trade-In Promotions Eligibility List Trade-In Promotions Eligibility List Eligible trade-in products Manufacturer Page Brother 1 Canon 1 Dell 1 HP 2 IBM 3 Konica 3 Lexmark 3 Oki 4 Ricoh 4 Samsung 4 Sharp 4 Xerox 5 Trade-In Promotions Eligibility List Brother Product Name Brother 9040 Brother MFC-240C Brother MFC-9700 Brother 9450 Brother MFC-3240C Brother MFC-9840 Series Brother DCP-7020 Brother MFC-3820CN Brother MFC-9880CDW Brother DCP-7040 Brother MFC-7420 Brother HL-4040CN Brother MFC-7424 Brother HL-4070CDW Brother MFC-7820N Brother HL-4100CN Brother MFC-8460N Brother HL-4200CN Brother MFC-8480N Brother HL-5140 Brother MFC-8670DN Brother HL-5150 Series Brother MFC-8680N Brother HL-5170 Series Brother MFC-8840 Series Brother HL-5240 Brother MFC-8860DN Brother HL-5250 Series Brother MFC-8870DW Brother HL -5370 Series Brother MFC-9420CN Brother HL-6050 Series Brother MFC-9440CN M Canon Product Name Canon C1022 Canon imageCLASS D860 Canon imageCLASS MF8170C Canon C2110 Canon imageCLASS D880 Canon C5550 Canon imageCLASS MF4150 Canon D1180 Canon imageCLASS MF6530 Canon MF9150 Canon imageCLASS MF6540 Canon MF9170 Canon imageCLASS MF6550 Dell Product Name Dell Laser 1710N Dell 5100CN Series Dell M5200 Series Dell 1125 MFP Dell 5210N Dell W5300 Dell 1230C Dell 5310N Dell 1600 MFP Dell 5330DN Dell 1815 MFP Dell Laser 1320C Series Dell 2135 Dell Laser 2130CN Dell 2145 Dell Laser 3000CN Dell 2230D Dell Laser 3010CN Dell 2330D Dell Laser 3110CN Dell 2335 Series Dell Laser 3115CN Dell 3100CN Dell Laser 3130CN -

![No. 1] Recent Developments 307 Control of the Aftermarket Through](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5986/no-1-recent-developments-307-control-of-the-aftermarket-through-815986.webp)

No. 1] Recent Developments 307 Control of the Aftermarket Through

No. 1] Recent Developments 307 Control of the Aftermarket Through Copyright Lexmark v. Static Control Components In an anticircumvention rulemaking hearing before the Copyright Office,1 the current Register of Copyrights asked a question of the former Register of Copyrights, who was representing Lexmark Inter- national, Inc. (“Lexmark”): MS. PETERS: Could you respond to Mr. Green- stein’s parade of horribles of, you know, the ball point pen, . the car; all of the items in commerce that could in fact be controlled by a computer pro- gram so that the original manufacturer is the only one who can do replacement parts? MR. OMAN: This is, in my view, speculation.2 Mr. Oman, understandably, was arguing that the only question at hand was the particular dispute between his client and Static Control Components, Inc. (“SCC”) regarding SCC’s sale of microchips that enabled the reuse of Lexmark’s toner cartridges. However, broad questions of policy regarding control of interoperability and the avail- ability of replacement parts for almost any item of commerce were in fact on the line. The same type of copyright enforcement scheme at issue in the controversy between Lexmark and SCC could be used to require consumers to buy gas from the same company that sold their cars, compact discs from the same company that sold their stereos, and milk from the same company that sold their refrigerators. Lexmark, a manufacturer and supplier of printers and the toner cartridges that function with those printers,3 and SCC, a manufacturer and supplier of parts to the toner cartridge remanufacturing industry,4 1. -

Lexmark-Xc4150-Brochure-Pdf.Pdf

XC4150 Powerful color A4 multifunction device in a compact design Affordable Productivity Workflow Sensitive data Cut costs in-house boosting speed, smoothing stays secure while being color production functionality solutions environmentally and reliability and flexibility responsible Lexmark XC4150 Get more power and save money Save time with the XC4150’s integrated software and solutions. Work from wherever, print where you want with Stay productive with print and scanning speeds fast enough to mobile printing from iOS, Android and Windows keep work moving. Look professional with gorgeous color. Mobile devices and optional wireless and NFC direct mobile printing from smartphones and tablets. The } Brilliant color in an affordable, space-saving device XC4150 is also Google Cloud Print, Apple Airprint 1.5 } Up to 50 pages per minute† print speeds and Mopria ready. } Spend less time on supplies with high-yield toner capacity and Better access for all with the tilting eTask panel that shake-free science makes the interface viewable for users at all heights, } Expandable universal input trays drawers and paper guides that move effortlessly, and standard headphone jack and talk-back features to Speed for productivity with the help users with limited vision engage with the device‡. functionality and reliability you need Productivity stays high when even large color print jobs complete quickly. Thanks to print speeds of up to 50 ppm. Minimize wait time with XC4150’s ability to print a single color page in as little as 5 seconds. Convenient direct printing from flash drives, network drives or online servers save you even more time. Power through complex print jobs with large, high-resolution photos and graphics. -

September 2000 User's Guide for Macintosh OS

User’s Guide for Macintosh OS 8.6 and 9 September 2000 www.kodak.com/go/homeprinting Edition: September 2000 The following paragraph does not apply to any country where such provisions are inconsistent with local law: LEXMARK INTERNATIONAL, INC., PROVIDES THIS PUBLICATION “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Some states do not allow disclaimer of express or implied warranties in certain transactions; therefore, this statement may not apply to you. This publication could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically made to the information herein; these changes will be incorporated in later editions. Improvements or changes in the products or the programs described may be made at any time. Comments about this publication may be addressed to Lexmark International, Inc., Department F95/032-2, 740 West New Circle Road, Lexington, Kentucky 40550, U.S.A. In the United Kingdom and Eire, send to Lexmark International Ltd., Marketing and Services Department, Westhorpe House, Westhorpe, Marlow Bucks SL7 3RQ. Lexmark may use or distribute any of the information you supply in any way it believes appropriate without incurring any obligation to you. You can purchase additional copies of publications related to this product by calling 1-800-553-9727. In the United Kingdom and Eire, call 0628-481500. In other countries, contact your point of purchase. References in this publication to products, programs, or services do not imply that the manufacturer intends to make these available in all countries in which it operates. -

Lexmark 1100 Color Jetprinter User's Guide

Lexmark 1100 Color Jetprinter User’s Guide First Edition (March 1998) The following paragraph does not apply to any country where such provisions are inconsistent with local law: LEXMARK INTERNATIONAL, INC. PROVIDES THIS PUBLICATION “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Some states do not allow disclaimer of express or implied warranties in certain transactions, therefore, this statement may not apply to you. This publication could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically made to the information herein; these changes will be incorporated in later editions. Improvements or changes in the products or the programs described may be made at any time. A form for reader’s comments is provided at the back of this publication. If the form has been removed, comments may be addressed to Lexmark International, Inc., Department F95/035-3, 740 New Circle Road N.W., Lexington, Kentucky 40550, U.S.A. In the United Kingdom and Eire, send to Lexmark International Ltd., Marketing and Services Department, Westhorpe House, Westhorpe, Marlow Bucks SL7 3RQ. Lexmark may use or distribute any of the information you supply in any way it believes appropriate without incurring any obligation to you. You can purchase additional copies of publications related to this product by calling 1- 800-553-9727. In the United Kingdom and Eire, call 0628-481500. In other countries, contact your point of purchase. Lexmark, ColorFine, and Lexmark with diamond design are trademarks of Lexmark International, Inc., registered in the United States and/or other countries. -

Lexmark XM1145 and XM3150 Monochrome Laser MFP

Lexmark XM1145 and XM3150 Monochrome Laser MFP Model shown features additional options Powerful. Compact. Mono Duplex Solutions Duplex Security Up to 4.3-Inch or Network Front USB Printing RADF 50 ppm 7-Inch Touch Screen 12WW1740 Lexmark XM1145 and XM3150 Why Lexmark. Founded in 1991 from an IBM heritage in Lexington, Kentucky, Lexmark is focused on delivering tailored solutions to solve the unique challenges businesses face. Lexmark's broad portfolio of high quality products, solutions, and services help improve productivity, increase efficiency and empower employees to perform at their best. Eco-responsible. Printing responsibly and reducing the impact of printing on the environment is a win for your business and your budget. Our goal is to design, package and deliver innovative products and solutions that produce high quality output with reliable performance. And at the same time, help you minimize the number of cartridges you use over the life of a printer and conserve paper and energy. The Lexmark Cartridge Collection Program provides a variety of methods for free returns of your empty cartridges to Lexmark or our collection partners. Program availability and details vary by country. Environmental protection is a shared responsibility. Through work with industry groups, Lexmark helps guide the formation of standards and guiding principles for environmental sustainability. Our memberships include AeA Europe Ecma International Electronics Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC) DIGITALEUROPE European Information & Communications Technology Industry Association (EICTA) Information Technology Industry Council (ITI) Environmental Leadership Council 12WW1740 Lexmark XM1145 and XM3150 Overview Powerful performance. The Lexmark XM1145 and XM3150 multifunction systems will help propel your business forward. -

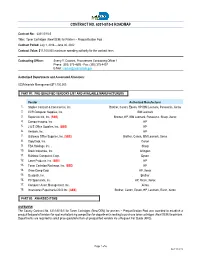

Contract No. 6301-5/15-5 Roadmap

CONTRACT NO. 6301-5/15-5 ROADMAP Contract No.: 6301-5/15-5 Title: Toner Cartridges (New/OEM) for Printers – Prequalification Pool Contract Period: July 1, 2016 – June 30, 2022 Contract Value: $11,100,000 maximum spending authority for the contract term Contracting Officer: Sherry Y. Crockett, Procurement Contracting Officer 1 Phone: (305) 375-4693 - Fax: (305) 375-4407 E-Mail: [email protected] Authorized Departments and Associated Allocation: ISD/Materials Management $11,100,000. PART #1: PRE-QUALIFIED VENDORS LIST AND AVAILABLE MANUFACTURERS Vendor Authorized Manufacturer 1. Staples Contract & Commercial, Inc. Brother, Canon, Epson, HP IBM Lexmark, Panasonic, Xerox 2. CVR Computer Supplies, Inc. IBM Lexmark 3. Replenish Ink, Inc. (SBE) Brother, HP, IBM Lexmark, Panasonic, Sharp, Xerox 4. Compu-Imaging, Inc. HP 5. J & E Office Supplies, Inc. (SBE) HP 6. Amitesh, Inc. HP 7. Galloway Office Supplies, Inc. (SBE) Brother, Canon, IBM Lexmark, Xerox 8. CopyCorp, Inc. Canon 9. FBA Holdings, Inc. Sharp 10. Brock Industries, Inc. Arlington 11. Rainbow Computers Corp. Epson 12. Laser Products, Inc. (SBE) HP 13. Toner Cartridge Recharge, Inc. (SBE) HP 14. Okee Comp Corp HP, Xerox 15. Qualpath, Inc. Brother 16. PC Specialists, Inc. HP, Ricoh, Xerox 17. Computer Asset Management, Inc. Xerox 18. Inversiones Papelmania 2000 Inc. (SBE) Brother, Canon, Epson, HP, Lexmark, Ricoh, Xerox 1. PART #2: AWARDED ITEMS OVERVIEW The County Contract No. 6301-5/15-5 for Toner Cartridges (New/OEM) for printers – Prequalification Pool was awarded to establish a prequalified pool of vendors for spot market pricing competition for departments seeking to purchase toner cartridges (New/OEM) for printers. -

PROSPECT Pro205 Print

5-Year !# 4 SINGLE INKS WIFI WARRANTY AUTO FEED 2-SIDED PROSPECT Pro205 Print. Copy. Scan. Fax. — Reliability: 5-Year Warranty (1) means you get a product designed to last — Convenience: Includes XL individual cartridges for 3X more pages (2) — Quality: Vizix print technology provides sharp text and vibrant images — Mobility: Enjoy the freedom of wireless printing (3) — Economical: Save paper and energy with Eco Mode TM Lexmark PROSPECT Small Offi ce Wireless 4-in-1 Pro205 PRINTING PRINT TECHNOLOGY Thermal Inkjet Vizix patented ink technology produces sharp text and true- COLOR TECHNOLOGY 4 Color Inkjet - Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black to-life photos with precise ink drop placement. Vizix also PRINT RESOLUTION, BLACK Up to 2400 x 1200 dpi produces print speeds up to 33 ppm black and 30 ppm color PRINT RESOLUTION, COLOR Up to 4800 x 1200 dpi (4) with 4x6” photos in as little as 24 seconds (5). Individual MAXIMUM PRINT SPEED (DRAFT, BLACK): UP TO 33 ppm cartridges allow you to replace only the color you need. MAXIMUM PRINT SPEED (DRAFT, COLOR): UP TO 30 ppm DUTY CYCLE, MAXIMUM 5000 pages per month PRINT NOISE LEVEL, OPERATING 50 dBA COPYING MAXIMUM COPY SPEED (DRAFT, BLACK): UP TO 25 cpm FEATURES & BENEFITS MAXIMUM COPY SPEED (DRAFT, COLOR): UP TO 21 cpm Rely on your printer Lexmark’s unmatched protection REDUCE / ENLARGE RANGE 25 - 400 % COPY NOISE LEVEL, OPERATING 47 dBA guarantee features a 5 year warranty and lifetime priority (1) FAXING phone support . MODEM SPEED 33.6 Kbps Increase your effi ciency Included individual XL cartridges save SCANNING resources and lower printing costs. -

Lexmark Pro200 Series User's Guide

Lexmark Pro200 Series User's Guide April 2009 www.lexmark.com Machine type(s): 4443 Model(s): 2W2, 2WE Contents Safety information.............................................................................5 About your printer.............................................................................6 Thank you for choosing this printer!...............................................................................................................................6 Minimizing your printer's environmental impact......................................................................................................6 Finding information about the printer...........................................................................................................................7 Understanding the parts of the printer..........................................................................................................................9 Ordering and replacing supplies...................................................12 Ordering ink cartridges.....................................................................................................................................................12 Using genuine Lexmark ink cartridges........................................................................................................................12 Replacing ink cartridges....................................................................................................................................................13 Ordering paper and other -

August 2000 User's Guide

User’s Guide August 2000 www.kodak.com/go/homeprinting Edition: August 2000 The following paragraph does not apply to any country where such provisions are inconsistent with local law: LEXMARK INTERNATIONAL, INC., PROVIDES THIS PUBLICATION “AS IS” WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Some states do not allow disclaimer of express or implied warranties in certain transactions; therefore, this statement may not apply to you. This publication could include technical inaccuracies or typographical errors. Changes are periodically made to the information herein; these changes will be incorporated in later editions. Improvements or changes in the products or the programs described may be made at any time. Comments about this publication may be addressed to Lexmark International, Inc., Department F95/032-2, 740 West New Circle Road, Lexington, Kentucky 40550, U.S.A. In the United Kingdom and Eire, send to Lexmark International Ltd., Marketing and Services Department, Westhorpe House, Westhorpe, Marlow Bucks SL7 3RQ. Lexmark may use or distribute any of the information you supply in any way it believes appropriate without incurring any obligation to you. You can purchase additional copies of publications related to this product by calling 1-800-553-9727. In the United Kingdom and Eire, call 0628-481500. In other countries, contact your point of purchase. References in this publication to products, programs, or services do not imply that the manufacturer intends to make these available in all countries in which it operates. Any reference to a product, program, or service is not intended to state or imply that only that product, program, or service may be used. -

Lexmark Interpret S405 Printer – Print Permanence Ratings1

www.wilhelm-research.com Category: Desktop All-in-One Inkjet Printers Updated June 5, 2010 (page 1 of 6) Lexmark Interpret S405 Printer – Print Permanence Ratings1 Ink System: Four Lexmark Vizix Series 100 inks in individual ink cartridges. Dye-based cyan, magenta, and yellow inks, and pigment-based black ink. High-capacity Vizix Se- ries 100XL ink cartridges are available for more economical document and photo print- ing. When printing on photo papers, the image is composed on only cyan, magenta, and yellow inks – the pigment black ink is not used. The thermal inkjet head is intended to last the life of the printer, but in the event of a head malfunction an user-installable replace- ment head is available from Lexmark. Print resolution up to 4800 x 1200 dpi. Maximum Paper Width: Single sheet: 8.5 inches. Paper sizes: U.S. letter; legal; A4; 3.5”x5” to 8.5”x14”; borderless photo sizes: 3.5”x5”; 4”x6”; 4”x8”; 4”x12”; 5”x7”; 6”x9”; 8”x10”; 8.5”x11”; 8.5”x14”;A; A4. Operating Systems: Windows XP, Vista, Windows 7; Mac OSX 10.4.4-10.6.x (Intel); 10.4.4- 10.5.x (PowerPC). PC-free copying. Compared with dye- or pigment-based Connectivity: Wi-Fi; USB 2.0. PC-free printing from common types of camera memory inks currently supplied by other major ©2010 Henry Wilhelm cards. Built-in fax capability. inkjet printer manufacturers, including Epson, Hewlett-Packard, Canon, Brother, The Wi-Fi enabled Lexmark Interpret S405 Special Features: Wi-Fi enabled for wireless printing.