[1]Draft Annex to Ispm 27: Striga Spp. (2008-009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Economic Consequences of Striga Hermonthica in Maize Production in Western Kenya

Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Economics The economic consequences of Striga hermonthica in maize production in Western Kenya Jenny Andersson Marcus Halvarsson Independent project ! 15 hec ! Basic level Agricultural Programme- Economics and Management Degree thesis No 669 ! ISSN 1401-4084 Uppsala 2011 The economic consequences of Striga in crop production in Western Kenya Jenny Andersson Marcus Halvarsson Supervisor: Hans Andersson, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Economics Assistant supervisor: Kristina Röing de Nowina, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Department of Soil and Environment Examiner: Karin Hakelius, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Department of Economics Credits: 15 hec Level: Basic C Course title: Business Administration Course code: EX0538 Programme/Education: Agricultural Programme-Economics and Management Place of publication: Uppsala Year of publication: 2011 Name of Series: Degree project No: 669 ISSN 1401-4084 Online publication: http://stud.epsilon.slu.se Key words: Africa, farming systems, maize, striga Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Department of Economics Acknowledgements This MFS project was funded by Sida and was a part of an on-going research project in Western Kenya led by Kristina Röing de Nowina. We appreciate the opportunity given to us to be a part of it. We would like to thank all farmers who were interviewed and made it possible to establish this report. We would also like to thank our supervisors Hans Andersson and Kristina Röing de Nowina for their support. Nairobi May 2011 Jenny Andersson and Marcus Halvarsson Summary Kenya is a country of 35 million people and is situated in Eastern Africa. -

Combined Control of Striga Hermonthica and Stemborers by Maize–Desmodium Spp

ARTICLE IN PRESS Crop Protection 25 (2006) 989–995 www.elsevier.com/locate/cropro Combined control of Striga hermonthica and stemborers by maize–Desmodium spp. intercrops Zeyaur R. Khana,Ã, John A. Pickettb, Lester J. Wadhamsb, Ahmed Hassanalia, Charles A.O. Midegaa aInternational Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE), P.O. Box 30772, Nairobi 00100, Kenya bBiological Chemistry Division, Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, Hertfordshire AL5 2JQ, UK Accepted 4 January 2006 Abstract The African witchweed (Striga spp.) and lepidopteran stemborers are two major biotic constraints to the efficient production of maize in sub-Saharan Africa. Previous studies had shown the value of intercropping maize with Desmodium uncinatum in the control of both pests. The current study was conducted to assess the potential role of other Desmodium spp., adapted to different agro-ecologies, in combined control of both pests in Kenya. Treatments consisted of intercropped plots of a Striga hermonthica- and stemborer-susceptible maize variety and one Desmodium sp. or cowpea, with a maize monocrop plot included as a control. S. hermonthica counts and stemborer damage to maize plants were significantly reduced in maize–desmodium intercrops (by up to 99.2% and 74.7%, respectively) than in a maize monocrop and a maize–cowpea intercrop. Similarly, maize plant height and grain yields were significantly higher (by up to 103.2% and 511.1%, respectively) in maize–desmodium intercrops than in maize monocrops or maize–cowpea intercrops. These results confirmed earlier findings that intercropping maize with D. uncinatum effectively suppressed S. hermonthica and stemborer infestations in maize resulting in higher crop yields. -

Striga (Witchweeds) in Sorghum and Millet: Knowledge and Future Research Needs

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ICRISAT Open Access Repository Striga (Witchweeds) in Sorghum and Millet: Knowledge and Future Research Needs A. T. Obilana 1 and K.V. Ramaiah 2 Abstract Striga spp (witchweeds), are notorious root hemiparasites on cereal and legume crops grown in the semi-arid tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, the southern Arabian Peninsula, India, and parts of the eastern USA. These weed-parasites cause between 5 to 90% losses in yield; total crop- loss data have been reported. Immunity in hosts has not been found. Past research activities and control methods for Striga are reviewed, with emphasis on the socioeconomic significance of the species. Striga research involving biosystematics, physiological biochemistry, cultural and chemical control methods, and host resistance are considered. We tried to itemize research needs of priority and look into the future of Striga research and control In light of existing information, some control strategies which particularly suit subsistence and emerging farmers' farming systems with some minor adjustments are proposed. The authors believe that a good crop husbandry is the key to solving the Striga problem. Introduction 60%), susceptibility (in about 30%), and resis- tance (in about 10%). On the other hand, in Striga species (witchweeds) are parasitic weeds maize, susceptibility has been the common reac- growing on the roots of cereal and legume crops tion as resistant varieties are still being identi- in dry, semi-arid, and harsh environments of fied and confirmed. The reaction of millet is tropical and subtropical Africa, Arabian Penin- complex, with ecological zone implications. -

UNDERSTANDING the ROLE of PLANT GROWTH PROMOTING BACTERIA on SORGHUM GROWTH and BIOTIC SUPPRESSION of Striga INFESTATION

University of Hohenheim Faculty of Agricultural Sciences Institute of Plant Production and Agroecology in the Tropics and Subtropics Section Agroecology in the Tropics and Subtropics Prof. Dr. J. Sauerborn UNDERSTANDING THE ROLE OF PLANT GROWTH PROMOTING BACTERIA ON SORGHUM GROWTH AND BIOTIC SUPPRESSION OF Striga INFESTATION Dissertation Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of “Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften” (Dr. sc. agr./Ph.D. in Agricultural Sciences) to the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences presented by LENARD GICHANA MOUNDE Stuttgart, 2014 This thesis was accepted as a doctoral dissertation in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree “Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften” (Dr.sc.agr. / Ph.D. in Agricultural Sciences) by the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences of the University of Hohenheim on 9th December 2014. Date of oral examination: 9th December 2014 Examination Committee Supervisor and Reviewer: Prof. Dr. Joachim Sauerborn Co-Reviewer: Prof. Dr.Otmar Spring Additional Examiner: PD. Dr. Frank Rasche Head of the Committee: Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Rainer Mosenthin Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my beloved wife Beatrice and children Zipporah, Naomi and Abigail. i Author’s Declaration I, Lenard Gichana Mounde, hereby affirm that I have written this thesis entitled “Understanding the Role of Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria on Sorghum Growth and Biotic suppression of Striga infestation” independently as my original work as part of my dissertation at the Faculty of Agricultural Sciences at the University of Hohenheim. No piece of work by any person has been included in this thesis without the author being cited, nor have I enlisted the assistance of commercial promotion agencies. -

How to Detect Horizontal Gene Transfers in Unrooted Gene Trees

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.24.449756; this version posted June 28, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. The Clade Displacement Index: how to detect horizontal gene transfers in unrooted gene trees Micha lAleksander Ciach [email protected] Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Mechanics University of Warsaw 2 Banacha St., 02-097, Warsaw, Poland Abstract While most genes of any organism are inherited vertically - i.e. from its parent organisms - sometimes they can be exchanged between unrelated species in a process known as the horizontal gene transfer (HGT). Studies of HGT contribute to our knowledge about the mechanisms of evolution, including the emergence of new pathogens, and a great deal of effort has been put into different methods of finding transferred genes. The golden standard of HGT detection is the analysis of the incongruence between the gene and the species trees. Those methods typically require rooted trees, in which the direction of evolution is known. Gene trees are typically unrooted, and rooting them is yet another step in HGT analysis, prone to errors which may lead to wrong conclusions. A natural question arises: can HGTs be detected in gene trees without rooting them at all? It turns out that, for a particular, yet broad, class of transfers, the answer to this question is: yes. It also turns out that the same method- ology can be applied to complement the bootstrap support in assessing the stability of gene tree topology. -

Desmodium Intortum Scientific Name Desmodium Intortum (Mill.) Urb

Tropical Forages Desmodium intortum Scientific name Desmodium intortum (Mill.) Urb. Synonyms Early flowering stage (cv. Greenleaf) Trailing, scrambling perennial herb or subshrub; image with Megathyrsus Basionym: Hedysarum intortum Mill.; Desmodium maximus cv. Petrie, S Qld, Australia hjalmarsonii (Schindl.) Standl.; Meibomia hjalmarsonii Schindl. Family/tribe Family: Fabaceae (alt. Leguminosae) subfamily: Faboideae tribe: Desmodieae subtribe: Desmodiinae. Morphological description Leaflets usually ovate-acute, Inflorescence a terminal or axillary with dark spots on the upper surface raceme Trailing, scrambling perennial herb or subshrub with (cv. Greenleaf) strong taproot. Stems 1.5 - 4.0 mm diameter, longitudinally grooved, often reddish-brown, sometimes ± glabrescent, mostly with dense, hooked or recurved hairs, glandular, sticky to the touch; ascendant, non- twining, rooting at the nodes if in prolonged contact with moist soil, to several metres long. Leaves pinnately trifoliolate; stipules 2 - 6 mm long, usually recurved, often persistent; petiole 3 - 5(- 9) cm long, pubescent; terminal leaflet usually ovate sometimes broadly elliptic, 5 Immature pods - 13 cm long, 2 - 7 cm wide, petiolule 6 - 12 mm long; Pods up to 12-articulate; articles semicircular or rhombic breaking up at lateral leaflets 3-10 cm long, 1.5 - 6 cm wide, petiolule 2 - maturity 4 mm; all laminae covered with ascending hairs on both surfaces; base rounded to truncate, apex acute, often with sparse reddish-brown/purplish marks on the upper surface. Racemes terminal or axillary, to 30 cm long; rachis with dense appressed to spreading hooked hairs, 2-flowered at each node; pedicel filiform, 6-10 mm; calyx 2.5-3 mm, 5-lobed, lowest lobe longest; corolla pink, purplish red to violet becoming bluish or greenish white, 9-11 mm. -

Under Striga Hermonthica Infestation

Effect of Nitrogen and Cytokinins on Photosynthesis and Growth of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) under Striga hermonthica infestation. Venasius Lendzemo Wirnkar A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirement for the degree of Master of Science in Crop Science (Protection) at Wageningen Agricultural University, The Netherlands Supervisors: lng. Aad van Ast and Prof. Dr lr Jan Goudriaan ~Department of Theoretical Production Ecology Wageningen Agricultural University Wageningen, The Netherlands January, 1998 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This study has been guided and supported by many persons to whom I would like to express my gratitude. I would like to express my sincere appreciation to lng. Aad van Ast who inspired me to carry out this study. His unrelenting assistance throughout the period of my study provided me with the much needed confidence. I would like to convey my gratitude to Prof. Dr lr Jan Goudriaan for accepting to supervise this piece of work. His constructive criticisms were invaluable. I am greatly indebted to Dr Wilco Jordi and lng. Geert Stoopen of AB-DLO for their contribution on plant hormones. Many thanks to Taede Stoker and colleagues, lng. Peter van Leeuwen, Ans Hofman, lng. Jacques Withagen, Esther Tempel and Slavica lvanovic for their assistance in some analyses and measurements. My special thanks go to Dr Kees Eveleens who made my dream of studying in Wageningen come true. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT LIST OF FIGURES LIST OF TABLES SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 The Striga problem 1 1.2 Striga hermonthica: Origin and Distribution 1 1. 3 Morphology and Biology 2 1.4 Effects of Striga hermonthica on sorghum 5 1.5 Theoretical background and objectives of the study 5 1.5.1 Striga hermonthica, nitrogen and host assimilation 5 1.5.2 Striga hermonthica and hormone balance 7 1.5.3 Cytokinins and plant growth and development 7 1.5.4 Aim and approach 8 2. -

Drought-Tolerant Desmodium Species Effectively Suppress Parasitic Striga Weed and Improve Cereal Grain Yields in Western Kenya

Crop Protection 98 (2017) 94e101 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Crop Protection journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/cropro Drought-tolerant Desmodium species effectively suppress parasitic striga weed and improve cereal grain yields in western Kenya * Charles A.O. Midega a, , Charles J. Wasonga a, Antony M. Hooper b, John A. Pickett b, Zeyaur R. Khan a a International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe), P.O. Box 30772, Nairobi 00100, Kenya b Biological Chemistry and Crop Protection Department, Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, Hertfordshire AL5 2JQ, UK article info abstracts Article history: The parasitic weed Striga hermonthica Benth. (Orobanchaceae), commonly known as striga, is an Received 7 February 2017 increasingly important constraint to cereal production in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), often resulting in Received in revised form total yield losses in maize (Zea mays L.) and substantial losses in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). 14 March 2017 This is further aggravated by soil degradation and drought conditions that are gradually becoming Accepted 17 March 2017 widespread in SSA. Forage legumes in the genus Desmodium (Fabaceae), mainly D. uncinatum and Available online 24 March 2017 D. intortum, effectively control striga and improve crop productivity in SSA. However, negative effects of climate change such as drought stress is affecting the functioning of these systems. There is thus a need Keywords: Striga to identify and characterize new plants possessing the required ecological chemistry to protect crops Climate change against the biotic stress of striga under such environmental conditions. 17 accessions comprising 10 Desmodium species of Desmodium were screened for their drought stress tolerance and ability to suppress striga. -

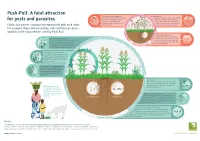

Push-Pull: a Fatal Attraction for Pests and Parasites

Push-Pull: A fatal attraction Stemborers and fall army worms Soil degradation The caterpillars cause massive damage Conventional cultivation methods (e.g. artificial for pests and parasites to the leaves and stalks of maize, fertilisers, ploughing and the removal of resulting in crop failures that crop residues) can lead to compaction of threaten the basic nutrition of many the soil, and affect the soil’s fertility as Plants and insects communicate extensively with each other. farming families. well as its water storage capacity. For example, they send out mating calls and false promises, and this is the characteristic used by Push-Pull. The striga root parasite Striga hermonthica, also known as The Push effect of desmodium witchweed, is a pest that “taps” into The scents given off by desmodium fulfil two the roots of the host plant, depriving functions; not only do they drive pests it of important nutrients and limiting its Th ts development significantly. (stemborers and the fall army worm) out of reat rves the field, but they also attract beneficial ened ha insects, such as ichneumon wasps. The Pull effect of elephant grass ct e Pu The leaves of elephant grass emit frag eff s l h rances into the air to attract stemborer l e u ff and fall army worm females away P e c from the maize when they are ready t to lay their eggs. The sticky sap of the elephant grass The sticky sap of the elephant grass affects the development of the pests’ newlyhatched caterpillars, and seriously reduces their chance of survival. -

Horizontal Gene Transfer Is More Frequent with Increased Heterotrophy and Contributes to Parasite Adaptation

Horizontal gene transfer is more frequent with increased heterotrophy and contributes to parasite adaptation Zhenzhen Yanga,b,c,1, Yeting Zhangb,c,d,1,2, Eric K. Wafulab,c, Loren A. Honaasa,b,c,3, Paula E. Ralphb, Sam Jonesa,b, Christopher R. Clarkee, Siming Liuf, Chun Sug, Huiting Zhanga,b, Naomi S. Altmanh,i, Stephan C. Schusteri,j, Michael P. Timkog, John I. Yoderf, James H. Westwoode, and Claude W. dePamphilisa,b,c,d,i,4 aIntercollege Graduate Program in Plant Biology, Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; bDepartment of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; cInstitute of Molecular Evolutionary Genetics, Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; dIntercollege Graduate Program in Genetics, Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; eDepartment of Plant Pathology, Physiology and Weed Science, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061; fDepartment of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; gDepartment of Biology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22904; hDepartment of Statistics, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; iHuck Institutes of the Life Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; and jDepartment of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802 Edited by David M. Hillis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, and approved September 20, 2016 (received for review June 7, 2016) Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) is the transfer of genetic material diverse angiosperm lineages (13, 14) and widespread incorpo- across species boundaries and has been a driving force in prokaryotic ration of fragments or entire mitochondrial genomes from algae evolution. -

Native Hemiparasite and Light Effects on Photoprotection and Photodamage in a Native Host Robert M

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health - Papers Faculty of Science, Medicine and Health 2015 Native hemiparasite and light effects on photoprotection and photodamage in a native host Robert M. Cirocco University of Adelaide Melinda J. Waterman University of Wollongong, [email protected] Sharon A. Robinson University of Wollongong, [email protected] Jose M. Facelli University of Adelaide Jennifer R. Watling University of Adelaide, [email protected] Publication Details Cirocco, R. M., Waterman, M. J., Robinson, S. A., Facelli, J. M. & Watling, J. R. (2015). Native hemiparasite and light effects on photoprotection and photodamage in a native host. Functional Plant Biology: an international journal of plant function, 42 (12), 1168-1178. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Native hemiparasite and light effects on photoprotection and photodamage in a native host Abstract Plants infected with hemiparasites often have lowered rates of photosynthesis, which could make them more susceptible to photodamage. However, it is also possible that infected plants increase their photoprotective capacity by changing their pigment content and/or engagement of the xanthophyll cycle. There are no published studies investigating infection effects on host pigment dynamics and how this relates to host susceptibility to photodamage whether in high (HL) or low light (LL). A glasshouse experiment was conducted where Leptospermum myrsinoides Schltdl. either uninfected or infected with Cassytha pubescens R.Br. was grown in HL or LL and pigment content of both host and parasite were assessed. -

GENETIC BASIS of Striga Hermonthica (Del.) BENTH RESISTANCE in WILD SORGHUM ACCESSIONS

GENETIC BASIS OF Striga hermonthica (Del.) BENTH RESISTANCE IN WILD SORGHUM ACCESSIONS Dorothy Annah Mbuvi (BSc) I56/28368/2014 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Masters of Science (Biotechnology) in the School of Pure and Applied Science of Kenyatta University June, 2017 ii DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree or other awards in any other university. Dorothy Annah Mbuvi Signature…………………… Date………………… Supervisors: We confirm that the candidate under our supervision carried out the work reported in this thesis. Dr. Steven Runo Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology Kenyatta University P.O Box 43844-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Signature……………………. Date ……………………… Dr. Mark Wamalwa Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology Kenyatta University P.O Box 43844-00100 Nairobi, Kenya Signature ……………………. Date……………………… iii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my dear parents Paul and Margaret for their perseverance, prayers, comfort and encouragement accorded to me during my studies. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I greatly appreciate my supervisors Dr. Steven Runo and Dr. Mark Wamalwa for the guidance they provided as I undertook my project. Your valuable time, ideas, productive discussions, instructive guidance and unlimited support during the research work are highly appreciated. To my dear parents, Paul and Margaret, my brother George and my sisters Mary and Ruth, I appreciate you for realizing the academic potential in me and encouraging me to further my studies. I am proud of you and forever grateful. Dad, the financial support you gave to me throughout the study will never be forgotten. I thank you mum for your encouragement when things were not working the way I wished to.