Panpsychism As Personal Experience: Resolving a Paradox

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

The Revelation of God, East and West: Contrasting Special Revelation in Western Modernity with the Ancient Christian East

Open Theology 2017; 3: 565–589 Analytic Perspectives on Method and Authority in Theology Nathan A. Jacobs* The Revelation of God, East and West: Contrasting Special Revelation in Western Modernity with the Ancient Christian East https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2017-0043 Received August 11, 2017; accepted September 11, 2017 Abstract: The questions of whether God reveals himself; if so, how we can know a purported revelation is authentic; and how such revelations relate to the insights of reason are discussed by John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, G. W. Leibniz, and Immanuel Kant, to name a few. Yet, what these philosophers say with such consistency about revelation stands in stark contrast with the claims of the Christian East, which are equally consistent from the second century through the fourteenth century. In this essay, I will compare the modern discussion of special revelation from Thomas Hobbes through Johann Fichte with the Eastern Christian discussion from Irenaeus through Gregory Palamas. As we will see, there are noteworthy differences between the two trajectories, differences I will suggest merit careful consideration from philosophers of religion. Keywords: Religious Epistemology; Revelation; Divine Vision; Theosis; Eastern Orthodox; Locke; Hobbes; Lessing; Kant; Fichte; Irenaeus; Cappadocians; Cyril of Alexandria; Gregory Palamas The idea that God speaks to humanity, revealing things hidden or making his will known, comes under careful scrutiny in modern philosophy. The questions of whether God does reveal himself; if so, how we can know a purported revelation is authentic; and how such revelations relate to the insights of reason are discussed by John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, René Descartes, G. -

Consciousness and Its Evolution: from a Human Being to a Post-Human

Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie Wydział Filozofii i Socjologii Taras Handziy Consciousness and Its Evolution: From a Human Being to a Post-Human Rozprawa doktorska napisana pod kierunkiem dr hab. Zbysława Muszyńskiego, prof. nadzw. UMCS Lublin 2014 Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Chapter 1: Consciousness, Mind, and Body …………………………………………………… 18 1.1 Conceptions of Consciousness …………………………………………………………. 18 1.1.1 Colin McGinn’s Conception of Consciousness ……………………………………….... 18 1.1.1.1 Owen Flanagan’s Analysis of Colin McGinn’s Conception of Consciousness ….…….. 20 1.1.2 Paola Zizzi’s Conception of Consciousness ………………………………………….… 21 1.1.3 William James’ Stream of Consciousness ……………………………………………… 22 1.1.4 Ervin Laszlo’s Conception of Consciousness …………………………………………... 22 1.2 Consciousness and Soul ………………………………………...………………………. 24 1.3 Problems in Definition of Consciousness ………………………………………………. 24 1.4 Distinctions between Consciousness and Mind ………………………………………... 25 1.5 Problems in Definition of Mind ………………………………………………………… 26 1.6 Dogmatism in Mind and Mind without Dogmatism ……………………………………. 27 1.6.1 Dogmatism in Mind …………………………………………………………………….. 27 1.6.2 Mind without Dogmatism …………………………………………………………….… 28 1.6.3 Rupert Sheldrake’s Dogmatism in Science …………………………………………….. 29 1.7 Criticism of Scientific Approaches towards Study of Mind ……………….…………… 30 1.8 Conceptions of Mind …………………………………………………………………… 31 1.8.1 Rupert Sheldrake’s Conception of Extended Mind …………………………………….. 31 1.8.2 Colin McGinns’s Knowing and Willing Halves of Mind ……………………………..... 34 1.8.3 Francisco Varela’s, Evan Thompson’s, and Eleanor Rosch’s Embodied Mind ………... 35 1.8.4 Andy Clark’s Extended Mind …………………………………………………………... 35 1.8.5 Role of Mind Understood by Paola Zizzi ………………………………………………. 36 1.9 Mind in Buddhism, Consciousness in Tibetan Buddhism ……………………………… 36 1.9.1 Mind in Buddhism ……………………………………………………………………… 36 1.9.2 B. -

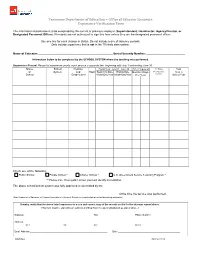

Experience Verification Form

Tennessee Department of Education – Office of Educator Licensure Experience Verification Form The information listed below is to be completed by the current or previous employer (Superintendent, Headmaster, Agency Director, or Designated Personnel Officer). Principals are not authorized to sign this form unless they are the designated personnel officer. Use one line for each change in status. Do not include leave of absence periods. Only include experience that is not in the TN state data system. Name of Educator: ________________________________________________ Social Security Number: _________________________ Information below to be completed by the SCHOOL SYSTEM where the teaching was performed. Experience Record: Please list experience yearly, each year on a separate line, beginning with July 1 and ending June 30. Name School Position Fiscal Year, July 01 - June 30 Time Employed % Time, Total of System and State Beginning Date Ending Date Months / Days Ex. Part-time, Days in Month/Day/Year Month/Day/Year Full-time School Year School Grade Level Per Year Check one of the following: Public School Private School * Charter School * U.S. Government Service Teaching Program * ** Please note: If non-public school you must identify accreditation. The above school/school system was fully approved or accredited by the ____________________________________________________________________ at the time the service was performed. (State Department of Education, or Regional Association of Colleges & Schools, or recognized private school accrediting -

PHILOSOPHY of RELIGION Philosophy 185 Spring 2016

PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION Philosophy 185 Spring 2016 Dana Kay Nelkin Office: HSS 8004 Office Hours: Monday 11-12, Friday 11-12, and by appointment Phone: (858) 822-0472 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.danakaynelkin.com Course Description: We will explore five related and hotly debated topics in the philosophy of religion, and, in doing so, address the following questions: (i) What makes something a religion? (ii) Is it rational to hold religious beliefs? Should we care about rationality when it comes to religious belief? (iii) Could different religions be different paths to the same ultimate reality, or is only one, at most, a “way to God”? (iv) What is the relationship between science and religion? (v) What is the relationship between morality and religion? Must religious beliefs be true in order for morality to exist? As we will see, the philosophy of religion leads naturally into just about every other area of philosophy, including epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and the history of philosophy, and into particular central philosophical debates such as the debate over the nature of free will. This means that you will gain insight into many fundamental philosophical issues in this course. At the same time, the subject matter can be difficult. To do well in the course and to benefit from it, you must be willing to work hard and to subject your own views (whatever they may be) to critical evaluation. Evaluating our conception of ourselves and of the world is one of the distinguishing features of philosophy. Requirements: Short reading responses/formulations of questions (150-200 words for each class meeting; 20 out of 28 required) 30% 1 paper in two drafts (about 2200 words) o first draft 10% (Due May 13) o second draft, revised after comments 25% (Due May 23) 1 take-home final exam (35%) (Due June 4, 11 am) up to 5% extra credit for participation in class group assignments and discussion. -

Moral Relativism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research New York City College of Technology 2020 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Carlo Alvaro CUNY New York City College of Technology How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/ny_pubs/583 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] 1 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Abstract This paper is a response to Park Seungbae’s article, “Defence of Cultural Relativism”. Some of the typical criticisms of moral relativism are the following: moral relativism is erroneously committed to the principle of tolerance, which is a universal principle; there are a number of objective moral rules; a moral relativist must admit that Hitler was right, which is absurd; a moral relativist must deny, in the face of evidence, that moral progress is possible; and, since every individual belongs to multiple cultures at once, the concept of moral relativism is vague. Park argues that such contentions do not affect moral relativism and that the moral relativist may respond that the value of tolerance, Hitler’s actions, and the concept of culture are themselves relative. In what follows, I show that Park’s adroit strategy is unsuccessful. Consequently, moral relativism is incoherent. Keywords: Moral relativism; moral absolutism; objectivity; tolerance; moral progress 2 The Incoherence of Moral Relativism Moral relativism is a meta-ethical theory according to which moral values and duties are relative to a culture and do not exist independently of a culture. -

Towards an Expanded Conception of Philosophy of Religion

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Int J Philos Relig DOI 10.1007/s11153-016-9597-7 ARTICLE Thickening description: towards an expanded conception of philosophy of religion Mikel Burley1 Received: 30 March 2016 / Accepted: 29 November 2016 © The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract An increasingly common complaint about philosophy of religion— especially, though not exclusively, as it is pursued in the “analytic tradition”—is that its preoccupation with questions of rationality and justification in relation to “theism” has deflected attention from the diversity of forms that religious life takes. Among measures proposed for ameliorating this condition has been the deployment of “thick description” that facilitates more richly contextualized understandings of religious phenomena. Endorsing and elaborating this proposal, I provide an over- view of different but related notions of thick description before turning to two specific examples, which illustrate the potential for engagement with ethnography to contribute to an expanded conception of philosophy of religion. Keywords Thick description · Expanding philosophy of religion · Radical pluralism · Ethnography · Interdisciplinarity · Animal sacrifice · Buddhism [I]f one wants to philosophize about religion, then one needs to understand religion in all its messy cultural-historical diversity. Insofar as one considers only a limited set of traditions or reasons, one’s philosophy of religion is limited. (Knepper 2013, p. 76) What’s ragged should be left ragged. (Wittgenstein 1998, p. 51) A common and thoroughly understandable complaint about much contemporary philosophy of religion is that its scope remains abysmally restricted. -

The Religious Naturalism of William James: a New Interpretation Through the Lens of Liberal Naturalism

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Bunzl, Jacob Herbert (2019) The Religious Naturalism of William James: A New Interpretation Through the Lens of Liberal Naturalism. Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) thesis, University of Kent,. DOI Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/81750/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html 1 The Religious Naturalism of William James A New Interpretation Through the Lens of ‘Liberal Naturalism’ Jacob Herbert Bunzl Abstract: This thesis argues that recent developments in philosophical naturalism mandate a new naturalistic reading of James. To that end, it presents the first comprehensive reading of James through the lens of liberal rather than scientific naturalism. Chapter 1 offers an extensive survey of the varieties of philosophical naturalism that provides the conceptual tools required for the rest the thesis, and allows us to provisionally locate James within the field. -

Professors of Paranoia?

http://chronicle.com/free/v52/i42/42a01001.htm From the issue dated June 23, 2006 Professors of Paranoia? Academics give a scholarly stamp to 9/11 conspiracy theories By JOHN GRAVOIS Chicago Nearly five years have gone by since it happened. The trial of Zacarias Moussaoui is over. Construction of the Freedom Tower just began. Oliver Stone's movie about the attacks is due out in theaters soon. And colleges are offering degrees in homeland-security management. The post-9/11 era is barreling along. And yet a whole subculture is still stuck at that first morning. They are playing and replaying the footage of the disaster, looking for clues that it was an "inside job." They feel sure the post-9/11 era is built on a lie. In recent months, interest in September 11-conspiracy theories has surged. Since January, traffic to the major conspiracy Web sites has increased steadily. The number of blogs that mention "9/11" and "conspiracy" each day has climbed from a handful to over a hundred. Why now? Oddly enough, the answer lies with a soft-spoken physicist from Brigham Young University named Steven E. Jones, a devout Mormon and, until recently, a faithful supporter of George W. Bush. Last November Mr. Jones posted a paper online advancing the hypothesis that the airplanes Americans saw crashing into the twin towers were not sufficient to cause their collapse, and that the towers had to have been brought down in a controlled demolition. Now he is the best hope of a movement that seeks to convince the rest of America that elements of the government are guilty of mass murder on their own soil. -

Panpsychism, Pan-Consciousness and the Non-Human Turn: Rethinking Being As Conscious Matter

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 11 Original Research Panpsychism, pan-consciousness and the non-human turn: Rethinking being as conscious matter Author: It is not surprising that in a time of intensified ecological awareness a new appreciation of 1 Cornel du Toit nature and the inanimate world arises. Two examples are panpsychism (the extension of Affiliation: consciousness to the cosmos) and deep incarnation (the idea that God was not only incarnated 1Research Institute for in human form but also in the non-human world). Consciousness studies flourish and are Theology and Religion, related to nature, the animal world and inorganic nature. A metaphysics of consciousness University of South Africa, emerges, of which panpsychism is a good example. Panpsychism or panconsciousness or South Africa speculative realism endows all matter with a form of consciousness, energy and experience. Corresponding author: The consciousness question is increasingly linked to the quantum world, which offers some Cornel du Toit, option in bridging mind and reality, consciousness and matter. In this regard Kauffman’s [email protected] notion of ‘triad’ is referred to as well as the implied idea of cosmic mind. This is related to the Dates: notion of ‘deep incarnation’ as introduced by Gregersen. Some analogical links are made Received: 11 Apr. 2016 between panpsychism and deep incarnation. Accepted: 02 Aug. 2016 Published: 24 Oct. 2016 How to cite this article: Introduction Du Toit, C., 2016, The matter of consciousness and consciousness as matter ‘Panpsychism, pan- consciousness and the Panpsychism is reviving in the twenty-first century. -

Indigenous and Cultural Psychology

Indigenous and Cultural Psychology Understanding People in Context International and Cultural Psychology Series Series Editor: Anthony Marsella, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii ASIAN AMERICAN MENTAL HEALTH Assessment Theories and Methods Edited by Karen S. Kurasaki, Sumie Okazaki, and Stanley Sue THE FIVE-FACTOR MODEL OF PERSONALITY ACROSS CULTURES Edited by Robert R. McCrae and Juri Allik FORCED MIGRATION AND MENTAL HEALTH Rethinking the Care of Refugees and Displaced Persons Edited by David Ingleby HANDBOOK OF MULTICULTURAL PERSPECTIVES ON STRESS AND COPING Edited by Paul T.P. Wong and Lilian C.J. Wong INDIGENOUS AND CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY Understanding People in Context Edited by Uichol Kim, Kuo-Shu Yang, and Kwang-Kuo Hwang LEARNING IN CULTURAL CONTEXT Family, Peers, and School Edited by Ashley Maynard and Mary Martini POVERTY AND PSYCHOLOGY From Global Perspective to Local Practice Edited by Stuart C. Carr and Tod S. Sloan PSYCHOLOGY AND BUDDHISM From Individual to Global Community Edited by Kathleen H. Dockett, G. Rita Dudley-Grant, and C. Peter Bankart SOCIAL CHANGE AND PSYCHOSOCIAL ADAPTATION IN THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Cultures in Transition Edited by Anthony J. Marsella, Ayda Aukahi Austin, and Bruce Grant TRAUMA INTERVENTIONS IN WAR AND PEACE Prevention, Practice, and Policy Edited by Bonnie L. Green, Matthew J. Friedman, Joop T.V.M. de Jong, Susan D. Solomon, Terence M. Keane, John A. Fairbank, Brigid Donelan, and Ellen Frey-Wouters A Continuation Order Plan is available for this series. A continuation order will bring deliv- ery of each new volume immediately upon publication. Volumes are billed only upon actual shipment. For further information please contact the publisher. -

Fragments for a Process Theology of Mormonism

Fragments for a Process Theology of Mormonism by James McLachlan I. SOME TENSIONS want to offer an interpretation of the ongoing revelation that is Mormonism from the point of view of Process Theology. This will Ibe a fragmentary interpretation because I cannot develop all of the possibilities in the space of one paper. Beyond the fragmentary character of this project there are at least two important tensions that will result from this attempt. eA. Religion and Theology First, there is always the possibility that one might take the theological reflection as the Mormon revelation and reduce it to that. This is the mis- take that theologians have made for millennia and is certainly the mistake that Sterling McMurrin makes in his pioneering classic of Mormon Theology: The Theological Foundations of the Mormon Religion. I believe that Ninian Smart is correct when he says that the theological/doctrinal is only one element of the religious which includes other elements; they are social, material, ritual, narrative/mythological, ethical, and perhaps most Element Vol. 1 Iss. 2 (Fall 2005) 1 Element importantly experiential.1 Thus theology is certainly not the foundation of a religion, but when we approach the religion through theoretical reflection it certainly appears to be. But when we are involved in concrete praxis, whether it is in temple work, working in the cannery, or just look- ing at a friend, the idea of our theological reflections as the foundation of our religion fades into the background. But it is far too simple to sim- ply split the theological from the other elements of religious life and say (as I have done in the recent past) that religious experience and narrative precedes everything.