Concerning Ernő Foerk's Documentation of Historic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frommer's Budapest & the Best of Hungary, 5Th Edition

00 549944 FM.qxd 3/18/04 10:42 AM Page i Budapest & the Best of Hungary 5th Edition by Joseph S. Lieber & Christina Shea with Erzsébet Barát Here’s what the critics say about Frommer’s: “Amazingly easy to use. Very portable, very complete.” —Booklist “Detailed, accurate, and easy-to-read information for all price ranges.” —Glamour Magazine “Hotel information is close to encyclopedic.” —Des Moines Sunday Register “Frommer’s Guides have a way of giving you a real feel for a place.” —Knight Ridder Newspapers 00 549944 FM.qxd 3/18/04 10:42 AM Page ii Published by: Wiley Publishing, Inc. 111 River St. Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774 Copyright © 2004 Wiley Publishing, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except as permitted under Sections 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978/750-8400, fax 978/646-8600. Requests to the Publisher for per mission should be addressed to the Legal Department, Wiley Publishing, Inc., 10475 Crosspoint Blvd., Indianapolis, IN 46256, 317/572-3447, fax 317/572- 4447, E-Mail: [email protected]. Wiley and the Wiley Publishing logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and/or its affiliates. -

The Model of Matthias Church, Created by Frigyes Schulek, and Its Role in the Design 2014 45 1 9 Fig

PP Periodica Polytechnica The model of Matthias Church, Architecture created by Frigyes Schulek, 45(1), pp. 9-18, 2014 and its role in the design DOI:10.3311/PPar.7458 http://www.pp.bme.hu/ar/article/view/7458 Creative Commons Attribution b Lilla Farbaky Deklava RESEARCH ARTICLE RECEIVED JANUARY 2014 Abstract When the preparation research and design of the current The medieval building of the Church of Our Lady in Buda ongoing restoration of the Church of Our Lady (= Matthias was converted to be the coronation church between 1872-96, Church; in Hungarian: Mátyás-templom) started in 2004, I also with the design and guidance of Frigyes Schulek, student participated as a researcher. In 2005, whilst on a construction of Friedrich Schmidt from Vienna. The story of the building visit with architect Zoltán Deák and some colleagues, we no- model, prepared during the construction, sheds light on the ticed some dirty debris, full of cobwebs. The finding proved design process. The model was created in the sculptor’s work- to be parts of the plaster model of Matthias Church, although shop of the construction office from 1877-1884, undergoing some details were different from the actual building and, un- several conversions just for the purpose of testing the different fortunately, several building parts were completely missing. design versions. This work was carried out in parallel with the At that time, they were only photographed and then moved construction until 1884. From analysing the resources, it could because of the start of the works; no extra attention was paid be concluded that Schulek designed the facade with two towers to them due to other pressing agenda. -

Hungarian Historical Review 2, No

Hungarian Historical Review 2, no. 2 (2013): 387–409 The Parish and Pilgrimage Church of St Elizabeth in Košice. Town, Court, and Architecture in Late Medieval Hungary. (Architectura Medii Aevi 6.). By Tim Juckes. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011. XII + 292 pp., 224 figs. In recent years, western scholars have shown a much welcome interest in the art of medieval Hungary. In the past the vast majority of studies were published by Hungarian scholars in Hungarian only, thus having little influence beyond the Hungarian-speaking world. Recognizing the problem, art museums in Hungary some time ago began publishing works in at least one other language besides Hungarian – a relevant case in point is the catalogue of the 2006 Sigismund- exhibition, published in German and French versions as well. Recently, more and more monographic works have been published in English or German – primarily by Hungarian, Slovak and Romanian scholars, but also in increasing number by people for whom this is not native territory. The most recent sign of this is the monograph of Tim Juckes on the church of St Elizabeth in Kassa (Košice, Slovakia), which is based on the author’s doctoral dissertation defended at the Courtauld Institute of Art, London. He has already published a number of studies about the subject, but now the results of his research are published by a major publisher in the form of a monograph of 292 pages.1 Hopefully, this publishing activity—including the future work of Tim Juckes as well—will eventually lead to a point where this part of Europe will no longer be a terra incognita on the map of medieval Europe. -

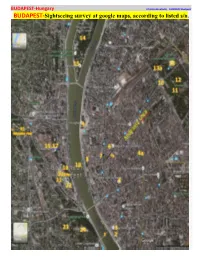

BUDAPEST-Sightseeing Survey at Google Maps, According to Listed S/N

BUDAPEST-Hungary Christos Gkoutzelis, HUNGARY-Budapest BUDAPEST-Sightseeing survey at google maps, according to listed s/n. 1. Liberty Bridge (Szabadsag hid) Liberty Bridge (Szabadság híd,is maybe the less attractive bridge in the city center ) is the one located at the southern end of city center, leading to Gellert Hill. The 333.6 m long bridge was built between 1894 and 1896. Its middle part was destroyed during World War II but it was rebuilt in 1945, and further restoration work was conducted to eliminate all war-related damage between 2007 and 2009. The bridge's main ornaments, four falcon-like bronze statues sitting on top of the bridge's four central masts (these are actually turuls, a mythological bird that represents power, strength and nobility in Hungary), were also restored. The bridge was originally named after the Emperor Franz Joseph, but it was renamed Liberty Bridge when the country was liberated from the Nazi occupation by the Soviet army at the end of World War II in 1945. The same year, the Liberation Monument was erected at the top of Gellert Hill. This imposing statue takes on the form of a woman holding a palm leaf above her head and can best be admired while crossing the bridge. 2. Corvinus University of Budapest (250m,3min from Szabadsag hid) In 1846, József Industrial School was opened gates for economics and trade for upper grade students. The immediate forerunner of the Corvinus University,the Faculty of Economics of the Royal Hungarian University, was established in 1920. The University admitting more than 14,000 students offers educational programmes inagricultural sciences, business administration, economics, and social sciences, and most these disciplines assure it a leading position in Hungarian higher education and is among the best institutions on various national and international rankings. -

Library Serving Our Users Our Catalogues and How to Use Them

MAIN HOME PAGE/GENERAL INFORMATION REGISTRATION WITH THE LIBRARY SERVING OUR USERS OUR CATALOGUES AND HOW TO USE THEM SUPPORTED BME OMIKK PDF READER: GENERAL INFORMATION CONTACT INFORMATION IN PERSON: HOW to finD US: BY PHONE: Opening hours: Monday-Friday: 9:00 – 20:00. By tram: 18, 19, 41, 47, 49, 118 463-1069, 463-3534, 463-3489 (Reference The promotional material has been Any changes are announced on the Library’s from the stop at Szent Gellért tér and Information Service) funded by NKA (Nemzeti Kulturális homepage and on notices displayed in the Libray. By bus: 7,86,173,233 E 463-1790 (Circulation: loans, renewals, Alap - Basic National Cultural Fund). from the stop at Szent Gellért tér reservations) Library building: 1111 Budapest, Budafoki út 4-6. 463-2441 (Management) Library management: 1111 Budapest, Műegyetem BY POST: Fax: 463-2440 (Management) rkp. 3. K.I. 61. 1018 Budapest, Pf. 91. E-mail: [email protected] OUR PRICES Contact information on the Library’s different organisational units is available in the online telephone directory of the University, and on our homepage under the menu ”About us” OUR READING ROOMS DIGITISATION IN THE LIBRARY LIBRARY EVENTS FROM OUR HISTORY MAIN HOME PAGE/GENERAL INFORMATION REGISTRATION WITH THE LIBRARY SERVING OUR USERS OUR CATALOGUES AND HOW TO USE THEM GENERAL INFORMATION CONTACT INFORMATION BME OMIKK is a double- Reference anD information serVice function library: it is both Library Building, groundfloor, Rooms 1 and 12, a university library and a Phone: 463-3534, 463-3489, 463-1069 specialised public library with e-mail: [email protected] national duties and services. -

The Central Library of the Budapest University of Technology (Formerly Royal Joseph University) and the Mural of Its Reading-Room

Bálint Ugry 189 Between Modernity and Tradition: The Central Library of the Budapest University of Technology (formerly Royal Joseph University) and the Mural of its Reading-room The first separate library buildings in Hungary By the mid-19th century with the appearance of the public libraries and the increasing rate of publishing, the library as an issue had transformed, as well. The requirement was to have one or more reading-rooms, some smaller research rooms and several big and possibly exten- sible storages (magazines) in the new type of library. Separate library buildings had appeared across Europe. The transformation of the libraries challenged the renewal of their decoration, as well as their relationship with the tradition. Before the First World War three separate library buildings were erected in the territory of Hungary (as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire): two in Budapest, and one in Kolozsvár (today: Cluj-Napoca, Romania).1 The construction of the first separate library building in Hungary started in 1873, the year, when Budapest, a European metropolis came into existence upon the unification of three towns, Pest, Buda and Óbuda. The Central Library of the University of Budapest (today: Eötvös Loránd University) was built according to the plans of the architects Antal Szkalnitzky (1836–1878) and Henrik Koch (1837–1889), and its construction was finished in 1875.2 1. The Central Library of the University of Budapest. Photograph by György Klösz, c. 1880 2. The reading-room of the Central Library of the University of Budapest. Photograph by György Klösz, c. 1880 1. Lajos Németh (Ed.), Magyar művészet 1890–1900. -

The Places of Memory in a Square of Monuments: Conceptions of Past, Freedom and History at Szabadság Tér

Page 1 of 34 Erik Thorstensen. “The Places of Memory in a Square of Monuments: Conceptions of Past, Freedom and History at Szabadság Tér. AHEA: E-journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 5 (2012): http://ahea.net/e-journal/volume-5- 2012 The Places of Memory in a Square of Monuments: Conceptions of Past, Freedom and History at Szabadság Tér Erik Thorstensen, The Center for Studies of Holocaust and Religious Minorities, Norway Abstract: In this paper I try to approach contemporary Hungarian political culture through an analysis of the history of changing monuments at Szabadság Tér in Budapest. The paper has as its point of origin a protest/irredentist monument facing the present Soviet liberation monument. In order to understand this irredentist monument, I look into the meaning of the earlier irredentist monuments under Horthy and try to see what monuments were torn down under Communism and which ones remained. I further argue that changes in the other monuments also affect the meaning of the others. From this background I enter into a brief interpretation of changes in memory culture in relation to changes in political culture. The conclusions point toward the fact that Hungary is actively pursuing a cleansing of its past in public spaces, and that this process is reflected in an increased acceptance of political authoritarianism. Keywords: monuments, Budapest, irredentism, memory, public spaces Biography: Erik Thorstensen has been an educator at the Center for Studies of Holocaust and Religious Minorities, Norway, since 2005. Previously he did research in ethics and lectured in history of religions at the University of Oslo. -

Powered by TCPDF ( 6 the REMARKABLE HUNGARIAN PARLIAMENT BUILDING TABLE of CONTENTS TABLE of CONTENTS

Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 6 THE REMARKABLE HUNGARIAN PARLIAMENT BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 10 INTRODUCTION 13 AT FIRST GLANCE 15 DIMENSIONS 18 FUNCTION 21 StYLE 23 ORNAMENtatION 26 ORDER 31 HOW IT WAS BUILT 32 THE PLOT 34 THE DECISION AND THE TENDER 39 IMRE StEINDL, DESIGNER, AND BUILDER 45 THE CONSTRUCTION 51 A TRADITIONAL BUILDING WITH MODERN TECHNOLOGY 57 THE PART OPEN TO THE PUBLIC 59 A MaIN ENTRANCE RaRELY USED 63 StaIRwaYS, LIFTS AND CORRIDORS 67 THE DOME HaLL AND THE HOLY CROWN 69 THE HOLY CROWN 71 THE TWO LOUNGES 72 GaLLERY OF CRAFTS 75 THE TWO CHAMBERS 83 IN THE TEMPEST OF HISTORY 85 THE BIRTH AND TRIBULatIONS OF THE paINTING OF ‘THE HUNGARIAN CONQUEST OF THE CaRpatHIAN BaSIN’ 7 89 A LESSON IN HISTORY IN TWENTY-FOUR PICTURES 94 THE PARLIAMENT BUILDING’S RESIDENTS 96 DURING AND AFTER THE SIEGE OF BUDapEST 99 THE PARLIAMENT BUILDING AFTER 1945 100 1956 BY THE PARLIAMENT BUILDING AND THE SQUARE 105 BEHIND CLOSED DOORS 107 ENDLESS CORRIDORS ADORNED BY MIKSA RÓTH’S WINDOWS 110 THÉK AND JUNGFER, THE TWO ‘MaSTER CRAFTSMEN’ INDUSTRIALISTS 113 THE HUNTER’S HaLL AND ITS PAINTERS 115 THE CROWN GUARDS 117 THE PARLIAMENT GUARDS 118 CaREtaKERS OF THE PARLIAMENT BUILDING 121 TRADITION AND INNOVATION 122 LIPÓTVÁROS, PARLIAMENT DISTRICT 125 THE StatUES ON THE SQUARE BEFORE 1945 131 THE SQUARE AFTER 1945 139 THE PARLIAMENtaRY LIBRARY 143 EXHIBITION SpaCES at THE MUSEUM OF THE NatIONAL ASSEMBLY 147 KOSSUTH SQUARE StatUE MINIpaEDIA 148 APPENDIX 150 PHOTO CREDITS BY PAGE 152 FURTHER READING IN LANGUAGES OTHER THAN HUNGARIAN 8 THE REMARKABLE HUNGARIAN PARLIAMENT BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS 9 INTRODUCTION nyone seeing the Hungarian Parliament The last third of the 19th century was a unique Abuilding for the first time will undoubt- period of tranquillity in Hungary’s turbu- edly be amazed. -

Part Three: Development of Conservation Theories

J. Jokilehto, A History of Architectural Conservation D. Phil Thesis, University of York, 1986 Part Three: Development of Conservation Theories Page 230 J. Jokilehto Chapter Thirteen Restoration of Classical Monuments 13.1 Principles created during the French Concorde, symbolized this attitude. Consequently, Revolution it was not until 1830s before mediaeval structures had gained a lasting appreciation and a more firmly The French Revolution became the moment established policy for their conservation. of synthesis to the various developments in the appreciation and conservation of cultural heritage. 13.2 Restoration of Classical Monuments Vandalism and destruction of historic monuments (concepts defined during the revolution) gave a in the Papal State ‘drastic contribution’ toward a new understanding In Italy, the home country of classical antiquity, where of the documentary, scientific and artistic values legislation for the protection of ancient monuments contained in this heritage, whcih so far had been had already been developed since the Renaissance closed away and forbidden to most people. Now for (or infact from the times of antiquity!), and where the the first time, ordinary citizens had the opportunity to position of a chief Conservator existed since the times come in contact with these unknown works of art. The of Raphael, patriotic expressions had often justified lessons of the past had to be learnt from these objects acts of preservation. During the revolutionary years, in order to keep France in the leading position even when the French troops occupied Italian states, and in the world of economy and sciences. It was also plundered or carried away major works of art, these conceived that this heritage had to be preserved in situ feelings were again reinforced. -

Concerning Ernő Foerk's Documentation of Historic

10.2478/jbe-2019-0013 concernIng ernŐ foerk’s docuMentatIon of HIstorIc MonuMents and aPPlIed arts actIvItIes András Hadik Before discussing the two areas of activity of the versatile architect Ernő Foerk, it is worthwhile to illuminate his family background and his early studies. Ernő Tivadar Foerk [1] (Ernst Theodor Förk) was born on February 3, 1868 in the centre of the Banat region, in the rapidly developing Timisoara (today Timişoara-Romania). Foerk’s father, Karl Gustav Förk, was born in Altenburg, Saxony in 1815 [2]. He received a thorough education, but after his father’s death he was forced to interrupt his studies, and undertook employment at the court printing house in his hometown. As an assistant - in Sweden and Norway, and then Germany, he “graduated” from his journey as an apprentice. In 1850 he arrived in Vienna. In 1852 he was invited to become a business manager at Márk Hazay’s printing house in Timişoara. He soon moved to the State Printing House, and in 1857, together with the Steger printing house, purchased the Beichel family press. In 1858 he received Austrian citizenship and then civil rights in Timişoara. In 1868 they founded the Neue Temesvarer Zeitung. From 1871 he became the sole owner of the printing press. Förk edited the German calendar, was the responsible publisher of Temesvarer Wochenblatt and Der Sammler (The Collector), in which many of his stories and poems appeared. Among others, Südungarische Ackerbau-Zeitung, the Südungarische Lloyd, the Südungarische Bote, and the Timisoara Newsletter were produced at Förk’s Press. He was president of the Printers’ Aid Association of the town, which was the first such organization in Hungary and was also a member of the city council for several years. -

Report on the Reactive Monitoring Mission to Budapest, Including the Banks of the Danube, the Buda Castle Quarter and Andrassy Avenue

World Heritage 37 COM Patrimoine mondial Distribution limted/ limitée/ Paris, 17 May 2013 Original: English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION ORGANISATION DES NATIONS UNIES POUR L'EDUCATION, LA SCIENCE ET LA CULTURE CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE CONVENTION CONCERNANT LA PROTECTION DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL, CULTUREL ET NATUREL WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE / COMITE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL Thirty-seventh session / Trente-septième session Phnom Penh, Cambodia / Phnom Penh, Cambodge 16-27 June 2013 / 16-27 juin 2013 Item 7 of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List and/or on the List of World Heritage in Danger. Point 7 de l’Ordre du jour provisoire: Etat de conservation de biens inscrits sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial et/ou sur la Liste du patrimoine mondial en péril JOINT WORLD HERITAGE CENTRE/ICOMOS REACTIVE MONITORING MISSION REPORT / RAPPORT DE MISSION DU SUIVI REACTIF CONJOINTE DU CENTRE DU PATRIMOINE MONDIAL ET DE L’ICOMOS BUDAPEST, INCLUDING THE BANKS OF THE DANUBE, THE BUDA CASTLE QUARTER AND ANDRASSY AVENUE (HUNGARY) / BUDAPEST, AVEC LES RIVES DU DANUBE, LE QUARTIER DU CHATEAU DE BUDA ET L’AVENUE ANDRASSY (HONGRIE) 25 February – 1 March 2013 / 25 février – 1 mars 2013 This mission report should be read in conjunction with Document / Ce rapport de mission doit être lu conjointement avec le document suivant : WHC-13/37.COM/7B.ADD REPORT ON THE REACTIVE MONITORING MISSION TO BUDAPEST, INCLUDING -

Faculty of Lifelong Learning

School of Arts Module Outline Module Title Study Trip: Budapest Module Code ARVC249H4 Programme Cert HE History of Art Credits/Level 15 credits at Level 4 Class Dates Week of 11-15 May 2020 + pre-session 25 Apr 2020. Term Dates 27 Apr to 10 Jul 2020 Taught By Dr Kasia Murawska-Muthesius Module Description Budapest was one of the most dynamic nineteenth-century European metropolises, rivalling Vienna and Paris. The visit looks at the complex history of the Kingdom of Hungary, but it focuses on the massive impetus given to the city by the “Compromise” of 1867, when Austria granted Hungary virtual self-rule within the Habsburgian Empire. It led to a stupendous urban growth, lavish boulevards, the Neo-Gothic Parliament building outdoing the London example, as well to monumental art museums. Painting celebrated Hungarian life and history before joining symbolist and fauvist trends. Uniquely, Budapest preserved its national version of a typical late 19th century word fair, the Millennium Exhibition with its panoply of buildings historical styles. A rich Hungarian version of Art Nouveau emerged in the singular work of Ődön Lechner. Key Topics Covered Medieval to Neo-Classicism: Turkish Baths; Buda; St. Stephens’ Basilica Pest; Esztergom. 19th-century urbanism: bridges over the Danube; the Fishermen’s Bastion; Metropolitan layouts in Pest: Andrassy Avenue and its underground railway; Millenium Square. Neo-Gothic: Europe’s most spectacular Parliament Building vs. Neo-Baroque: Palace of Justice. Hungarian National Museum, Hungarian National Gallery (Hungarian art ); Museum of Fine Arts (European art); the Applied Arts Museum; Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art. Diversity of styles at the 1896 Millennial Exhibition; copy of Vajdahunyad Castle.