The Role of Heredity in Reading Disability. INSTITUTION Glassboro State Coll., N.J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8. Eligibility for Special Education Services A

8. Eligibility for Special Education Services a. Fact Sheets on i. ADHD Fact Sheet on Disabilities from NICHCY (http://nichcy.org/disability) ii. Autism Spectrum Disorders Fact Sheet iii. Blindness/Visual Impairment Fact Sheet iv. Cerebral Palsy Fact Sheet v. Deaf-Blindness Fact Sheet vi. Deafness and Hearing Loss Fact Sheet vii. Developmental Delay Fact Sheet viii. Down Syndrome Fact Sheet ix. Emotional Disturbance Fact Sheet x. Epilepsy Fact Sheet xi. Intellectual Disabilities Fact Sheet xii. Learning Disabilities Fact Sheet xiii. Other Health Impairment Fact Sheet xiv. Traumatic Brain Injury Fact Sheet b. Disability Worksheets for Eligibility for Special Education (from OSSE/DCPS) i. Other Health Impairment Disability Worksheet ii. Specific Learning Disability Worksheet iii. Emotional Disturbance Disability Worksheet Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder NICHCY Disability Fact Sheet #19 Updated March 2012 break down his lessons into gets to choose something fun several parts. Then they have he’d like to do. Having a him do each part one at a child with AD/HD is still a Mario’s Story time. This helps Mario keep challenge, but things are his attention on his work. looking better. Mario is 10 years old. When he was 7, his family At home, things have learned he had AD/HD. At changed, too. Now his What is AD/HD? the time, he was driving parents know why he’s so everyone crazy. At school, he active. They are careful to Attention-deficit/hyperac- couldn’t stay in his seat or praise him when he does tivity disorder (AD/HD) is a keep quiet. At home, he something well. -

Sampling Inner Experience in the Learning Disabled Population

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1992 Sampling inner experience in the learning disabled population Barbara Lynn Schamanek University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Schamanek, Barbara Lynn, "Sampling inner experience in the learning disabled population" (1992). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 187. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/sa8u-f0vh This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Speech/Language Impairment Sheet

West Virginia State Department of Education Office of Special Education * 1-800-558-2696 * http://wvde.state.wv.us/osp/ Fact Speech/Language Impairment Sheet DEFINITION Voice: Speech impairment where the child’s voice has an IDEA defines a speech or language impairment as a abnormal quality of pitch, resonance, or loudness. communication disorder, such as stuttering, impaired articulation, a language impairment, or a voice Persistent voice issues can indicate problems such as impairment that adversely affects a child’s educational vocal cord nodules, which should be addressed. Some performance. students who have structural abnormalities, such as cleft palate or palatal insufficiency, may exhibit a nasal SPEECH DISORDERS sound to their speech. An otolaryngologist must verify Speech Sound Disorders: Speech impairment where the the absence or existence of structural or functional child has difficulty producing sounds. Most children pathology before voice therapy can be provided. make some mistakes as they learn to say new words. A speech sound disorder occurs when mistakes continue Dysphagia: Some children may have difficulty eating past a certain age. Every sound has a different range of (chewing and swallowing food) and drinking without ages when the child should make the sound correctly. aspiration. The speech-language pathologist may be involved in developing a plan, along with other team Speech sound disorders include problems with members, to ensure that the child is provided with safe articulation (making sounds) and phonological nourishment and hydration during school hours. processes (patterns of sounds). COMMUNICATION DISORDERS Sounds can be substituted (saying “tat” for “cat”), left Augmentative and Alternative Communication: the use off (saying “ca” instead of “cat”), added (saying “kwat” of an alternative to speaking as a substitute for speech instead of “cat”) or changed (saying the sound or to supplement speech. -

White Paper: Dyslexia and Read Naturally 1 Table of Contents Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc

Dyslexia and Read Naturally Cory Stai Director of Research and Partnership Development Read Naturally, Inc. Published by: Read Naturally, Inc. Saint Paul, Minnesota Phone: 800.788.4085/651.452.4085 Website: www.readnaturally.com Email: [email protected] Author: Cory Stai, M.Ed. Illustration: “A Modern Vision of the Cortical Networks for Reading” from Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read by Stanislas Dehaene, copyright © 2009 by Stanislas Dehaene. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Part I: What Is Dyslexia? . 3 Part II: How Do Proficient Readers Read Words? . 9 Part III: How Does Dyslexia Affect Typical Reading? . .. 15 Part IV: Dyslexia and Read Naturally Programs . 18 End Notes . 24 References . 28 Appendix A: Further Reading . 35 Appendix B: Program Scope and Sequence Summaries . 36 White Paper: Dyslexia and Read Naturally 1 Table of Contents Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc. Table of Contents 2 White Paper: Dyslexia and Read Naturally Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc. Read Naturally’s mission is to facilitate the learning necessary for every child to become a confident, proficient reader . Dyslexia is a reading disability that impacts millions of Americans . To support learners with dyslexia, educators must understand: n what dyslexia is and what it is not n how the dyslexic brain differs from that of a typical reader n how and why recommended reading interventions help To these ends, this paper supports educators to deepen their understanding of the instructional needs of dyslexic readers and to confidently select and use Read Naturally intervention programs, as appropriate . -

Early Help Better Future

Early Help Better Future A Guide to the Early Recognition of Dyslexia by Jean Augur Introduction In the past it was thought that the earliest that a child could be identified as having a dyslexic profile was at about the age of six. This was because, by six, the child was already giving cause for concern particularly as regards reading, writing and spelling, all very important skills in the school curriculum. With experience, however, and from the findings of research studies, it is now evident that there are many signs well before school age which may suggest such a profile and the consequent difficulties ahead. Parents and pre-school carers as well as educators in those early years are amongst those in the best position to recognise these signs, and to provide appropriate activities to help. Training in some of these activities will help to build firm foundations for later, more formal, training. What is Dyslexia? Dyslexia is best described as a specific difficulty in learning, in one or more of reading, spelling and written language which may be accompanied by difficulty in number work, short-term memory, sequencing, auditory and/or visual perception, and motor skills. It is particularly related to mastering and using written language – alphabetic, numeric and musical notation. In addition, oral language is often affected to some degree. Dyslexia occurs despite normal teaching and is independent of socio-economic background or intelligence. It is, however, more easily detected in those with average or above intelligence. 1 Some of the Early Signs which may suggest a Dyslexic Profile General · Family history of similar difficulties; · May have walked early but did not crawl – was a “bottom shuffler” or “tummy wriggler”; · Persistent difficulties in getting dressed efficiently; · Persistent difficulty in putting shoes on the correct feet; Just marking the shoes with “outside” may help to ease the difficulty. -

The Online Journal of Missouri Speech-Language-Hearing Association 2015

THE ONLINE JOURNAL OF MISSOURI SPEECH-LANGUAGE-HEARING ASSOCIATION 2015 The Online Journal of Missouri Speech- Language-Hearing Volume1; Number 1; 2015 Association © Missouri Speech-Language- Hearing Association 2015 Ray, Jayanti Annual Publication of the Missouri Speech- Language-Hearing Association Scope of OJMSHA The Online Journal of MSHA is a peer-reviewed interprofessional journal publishing articles that make clinical and research contributions to current practices in the fields of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology. The journal is also intended to provide updates on various professional issues faced by our members while bringing them the latest and most significant findings in the field of communication disorders. The journal welcomes academicians, clinicians, graduate and undergraduate students, and other allied health professionals who are interested or engaged in research in the field of communication disorders. The interested contributors are highly encouraged to submit their manuscripts/papers to [email protected]. An inquiry regarding specific information about a submission may be emailed to Jayanti Ray ([email protected]). Upon acceptance of the manuscripts, a PDF version of the journal will be posted online. Our first issue is expected to be published in August. This publication is open to both members and nonmembers. Readers can freely access or cite the article. 2 THE ONLINE JOURNAL OF MISSOURI SPEECH-LANGUAGE-HEARING ASSOCIATION 2015 The Online Journal of Missouri Speech-Language-Hearing Association Vol. 1 No. 1 ∙ August 2015 Table of Contents Story Presentation Effects on the Narratives of Preschool Children 8 From Low and Middle Socioeconomic Homes Grace E. McConnell Evidence-Based Practice, Assessment, and Intervention Approaches for 25 Children with Developmental Dyslexia Ryan Riggs Advocacy Training: Taking Charge of Your Future 37 Nancy Montgomery, Greg Turner, and Robert deJonge Working with Your Librarian 42 Cherri G. -

Differences. CM BEST COPY AVAILABLE

DOCUMENT RESUME ID 100 112 EC 070 982 MLR Project Child Ten Kit 3: Characteristicsof the Language Disabled Child. INSTITUTION Texas Education Agency, Austin. NOTE 51p.; For related information see EC 070975-992 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$3.15 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Behavioral Objectives; Exceptional Child Education; Instructional Materials; *Language Handicapped; Learning Disabilities; *Performance Based Teacher Education; Performance Criteria; *Student Characteristics IDENTIFIERS *Project CHILD ABSTRACT Presented is the third of 12 instructional kits, on characteristics of the language disabled (LD) child, for a performance based teacher education program which was developed by Project CHILD, a research effort to validate identification, intervention, and teacher education programs for LD children. Included in the kit are directions for preassessment tasks for the five performance objectives, a listing of the five performance objectives (such as correctly identifying three learning disabled children from five case histories), instructions for four learning experiences (such as using correct terminology to identify pantomimed behavior characteristics), a checklist for self-evaluation for each of the performance objectives, and guidelines for proficiency assessment of each objective. Also included are two descriptions of LD children intended to help the student identify individual differences. CM BEST COPY AVAILABLE PROJECT CHILD U.S. DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH, EDUCATION A WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN Ten Kit 3 ATOM IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY Texas Education Agency Austin, Texas 4 Texas Education Agency publications are not copyrighted. -

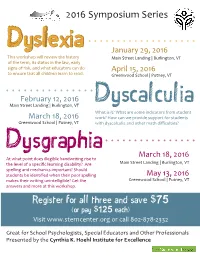

2016 Symposium Series

2016 Symposium Series Dyslexia January 29, 2016 This workshop will review the history Main Street Landing | Burlington, VT of the term, its status in the law, early signs of risk, and what educators can do April 15, 2016 to ensure that all children learn to read. Greenwood School | Putney, VT February 12, 2016 Dyscalculia Main Street Landing | Burlington, VT What is it? What are some indicators from student March 18, 2016 work? How can we provide support for students Greenwood School | Putney, VT with dyscalculia and other math difficulties? Dysgrap hia March 18, 2016 At what point does illegible handwriting rise to the level of a specific learning disability? Are Main Street Landing | Burlington, VT spelling and mechanics important? Should students be identified when their poor spelling May 13, 2016 makes their writing unintelligible? Get the Greenwood School | Putney, VT answers and more at this workshop. Register for all three and save $75 (or pay $125 each) Visit www.sterncenter.org or call 802-878-2332 Great for School Psychologists, Special Educators and Other Professionals Presented by the Cynthia K. Hoehl Institute for Excellence Friday, April 15, 2016 Dyslexia Greenwood School | Putney, Vermont The field of reading is rife with About the Presenter controversy. We not only disagree over Melissa Farrall, Ph.D. what constitutes a reading disorder, we is the author of Reading often bristle over the language that others Assessment: Linking Language, Literacy, and Cognition, use to describe one. The term, dyslexia, and the co-author of All elicits a wide range of reactions. About Tests & Assessments published by Wrightslaw. -

Part 7 Developmental Disabilities

Bringing It All Together You are a group leader on one of the ICF units at SDC, one of the clients in your group is Mickey, a 44-year-old man with Down Syndrome. He is sociable, but mischievous. He can say a few words, such as "toy", "no", and "hurt." He enjoys his vocational activity most of the time but has to be reminded, repeatedly. to get back to work (he has a job shredding paper). His physical treatment profile lists: hypothyroidism, constipation, dermatitis, GERD, and obstructive sleep apnea. When he is angry he vocalizes and pushes people; when he's happy he can be a charmer. 1. As a psychiatric technician you know that Down syndrome is: a. A disorder caused by gestational problems in the neonate b. A genetic abnormality c. Perinatal hypoxia d. Drug exposure during pregnancy Answer: B- Down syndrome, also called Trisomy 21- is a genetic disorder. Perinatal hypoxia has long been suspected of causing cerebral palsy, but there may be other factors involved. Drug exposure during pregnancy is usually worst with resultant F AS. 2. The common characteristics of Down are: a. Short stature, epicanthal fold, smallish head b. Long face, hand flapping c. .:Ylicrocephaly, hirshutism, and severe mental impairment d. Port wine stain Answer: A-Down syndrome. A more complete list would include: Poor muscle tone; Slanting eyes with folds of skin at the inner corners (callcd epicanthal folds); Hyperflexibility (excessive ability to extend the joints); Short, broad hands with a single crease across the palm on one or both hands; Broad feet with short toes; Flat bridge of the nose; Short, low-set ears; Short neck; Small head; Small oral cavity; and/or short, high-pitched cries in infancy. -

A Review of Tools/Objects Used in Articulation Therapy by Van Riper and Other Traditional Therapists

Volume 37 Number 1 pp. 69-96 2011 Review Article Horns, whistles, bite blocks, and straws: A review of tools/objects used in articulation therapy by van Riper and other traditional therapists Pam Marshalla (Marshalla Speech and Language) Follow this and additional works at: https://ijom.iaom.com/journal The journal in which this article appears is hosted on Digital Commons, an Elsevier platform. Suggested Citation Marshalla, P. (2011). Horns, whistles, bite blocks, and straws: A review of tools/objects used in articulation therapy by van Riper and other traditional therapists. International Journal of Orofacial Myology, 37(1), 69-96. DOI: https://doi.org/10.52010/ijom.2011.37.1.6 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of the International Association of Orofacial Myology (IAOM). Identification of specific oducts,pr programs, or equipment does not constitute or imply endorsement by the authors or the IAOM. International Journal of Orofacial Myology 2011, V37 HORNS, WHISTLES, BITE BLOCKS, AND STRAWS: A REVIEW OF TOOLS/OBJECTS USED IN ARTICULATION THERAPY BY VAN RIPER AND OTHER TRADITIONAL THERAPISTS PAM MARSHALLA, MA, CCC-SLP ABSTRACT The use of tools and other objects in articulation therapy has been bundled into new groups of activities called “nonspeech oral motor exercises” (NSOME) and ‘nonspeech oral motor treatments’ (NSOMT) by some authors. The purveyors of these new terms suggest that there is no proof that such objects aid speech learning, and they have cautioned students and professionals about their use. -

Through the Phonics Barrier

Through the Phonics Barrier Student Manual by Sibyl Terman and Charles Child Walcutt Originally published in Reading: chaos and cure McGraw-Hill, 1958 A Self-teaching Audio-Visual Approach to Reading Improvement Audio CD © 2003 by Donald Potter Through the Phonics Barrier The Consonants The c, g, and s have two sounds; qu = kw; x = ks b c d f g h j k l m n c g p qu r s t v w x y z s Rule I c says s before e i y cents city mice cycle c says k before a o u cat cow cut g says g before a o u game go gum ge says j at the end of a word age bridge 1 The Vowels The long vowels say their names a e i o u y ā ē ī ō ū ī Fat Ed is not up The short vowels are sounded as in “Fat Ed is not up.” a e i o u y ă ĕ ĭ ŏ ŭ ĭ a also says ah (ä) 2 Special Vowel Sounds Read: oo ou oy aw oo ow oi au Special Consonant Sounds 3 Vowel Digraphs These generally say the long sound of the first letter: ā ē ī ō ū ai ee ie oa ue ay ea oe ui ow Also: ei and ey say ē or ā ie says ē or ī ew and eu say ū or o͞o Vowels Followed by R er ir ur or ar Examples: her fir fur or car Rule 2 One vowel followed by one or two consonants is short. -

How to Help. a Guide for Parents and Teachers

CHILDREN WITH LEARNING DIFFICULTIES – HOW TO HELP. A GUIDE FOR PARENTS AND TEACHERS BY BELA RAJA Copyright – Bela Raja (2006) DEDICATION To my Spiritual Guru. I am blessed to receive her guidance. TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword Author‟s Note Preface Acknowledgements 1. The Differently Abled 2. What Is A Learning Disability And Why Does It Happen? 3. Different Aspects Of Learning Disabilities And Understanding The Terminology 4. Symptoms of Dyslexia – What To Look For? 5. Remedial Techniques Used To Teach And Strengthen Reading Skills 6. Phonics and Phonological Acquisition 7. Spelling 8. Cognitive Functions and Dysfunctions – How Do They Interfere With Learning? 9. Language Processing Disorders And Memory Deficits 10. Secondary Problems – Behavioural And Emotional 11. Behavioural Difficulties – Understanding and Management 12. Self Esteem In Children 13. Math 14. Strategies For Students With Math Difficulties 15.Learning Styles And Assessments 16.Dyspraxia 17.Gifted Children And Learning Difficulties 18. From The Heart… Voices Sight Words Useful Websites Bibliography FOREWORD I have always strongly believed that every individual has something special and unique to offer the world. However, conventional thinking has forced a one – dimensional view on the idea of success. Today, most parents look at aptitude only in terms of grades and certain skill sets. We often opine that only when a child has a certain type of talent, will s/he climb the citadels of success. But look at the history of human accomplishment – some of our greatest men and women have over come challenges to achieve success. Every child has something incredibly special about him or her and as a parent, we have to nurture that talent and always reassure the child about it‟s uniqueness.