Conservation Tillage Practices in California Irrigated Row Crop Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conservation Tillage and Organic Farming Reduce Soil Erosion

Conservation tillage and organic farming reduce soil erosion Steffen Seitz, Philipp Goebes, Viviana Loaiza Puerta, Engil Isadora Pujol Pereira, Raphaël Wittwer, Johan Six, Marcel G. A. van der Heijden, Thomas Scholten To cite this version: Steffen Seitz, Philipp Goebes, Viviana Loaiza Puerta, Engil Isadora Pujol Pereira, Raphaël Wittwer, et al.. Conservation tillage and organic farming reduce soil erosion. Agronomy for Sustainable De- velopment, Springer Verlag/EDP Sciences/INRA, 2019, 39 (1), pp.4. 10.1007/s13593-018-0545-z. hal-02422719 HAL Id: hal-02422719 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02422719 Submitted on 23 Dec 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Agronomy for Sustainable Development (2019) 39: 4 https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-018-0545-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Conservation tillage and organic farming reduce soil erosion Steffen Seitz1 & Philipp Goebes1 & Viviana Loaiza Puerta2 & Engil Isadora Pujol Pereira3 & Raphaël Wittwer4 & Johan Six2 & Marcel G. A. van der Heijden4,5 & Thomas Scholten1 Accepted: 12 November 2018 /Published online: 18 December 2018 # INRA and Springer-Verlag France SAS, part of Springer Nature 2018 Abstract The impact of different arable farming practices on soil erosion is only partly resolved, and the effect of conservation tillage practices in organic agriculture on sediment loss has rarely been tested in the field. -

SB661 a Glossary of Agriculture, Environment, and Sustainable

This publication from the Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service has been archived. Current information is available from http://www.ksre.ksu.edu. A Glossary of Agriculture, Environment, and Sustainable Development Bulletin 661 Agricultural Experiment Station, Kansas State University Marc Johnson, Director This publication from the Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service has been archived. Current information is available from http://www.ksre.ksu.edu. A GLOSSARY OF AGRICULTURE, ENVIRONMENT, AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT1 R. Scott Frey2 ABSTRACT This glossary contains general definitions of over 500 terms related to agricultural production, the environment, and sustainable develop- ment. Terms were chosen to increase awareness of major issues for the nonspecialist and were drawn from various social and natural science disciplines, including ecology, biology, epidemiology, chemistry, sociol- ogy, economics, anthropology, philosophy, and public health. 1 Contribution 96-262-B from the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station. 2 Professor of Sociology, Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66506-4003. 1 This publication from the Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service has been archived. Current information is available from http://www.ksre.ksu.edu. PREFACE Agricultural production has increased dramatically in the United States and elsewhere in the past 50 years as agricultural practices have evolved. But this success has been costly: water pollution, soil depletion, and a host of human (and nonhuman) health and safety problems have emerged as impor- tant side effects associated with modern agricultural practices. Because of increased concern with these costs, an alternative view of agricultural production has arisen that has come to be known as sustain- able agriculture. -

Tillage Implements Are Broadly Categorized Into Several Groups Depending on the Purpose for Which They Are Use: Primary Tillage Implements

Tillage implements are broadly categorized into several groups depending on the purpose for which they are use: Primary Tillage implements Implements used for opening and loosening of the soil are known as ploughs. Ploughs are used for primary tillage. Ploughs are of three types: wooden ploughs, iron or inversion ploughs and special purpose ploughs. Wooden plough or Indigenous plough Indigenous plough is an implement which is made of wood with an iron share point. It consists of body, shaft pole, share and handle. It is drawn with bullocks. It cuts a V shaped furrow and opens the soil but there is no inversion. Ploughing operation is also not perfect because some unploughed strip is always left between furrows. This is reduced by cross ploughing, but even then small squares remain unploughed. Soil Turning Ploughs Soil turning ploughs are made of iron and drawn by a pair of bullocks or two depending on the type of soil. These are also drawn by tractors. Mouldboard Plough The parts of mouldboard plough are frog or body, mouldboard or wing, share, landside, connecting, rod, bracket and handle. This type of plough leaves no unploughed land as the furrow slices are cut clean and inverted to one side resulting in better pulverisation. The animal drawn mouldboard plough is small, ploughs to a depth of 15 cm, while two mouldboard ploughs which are bigger in size are attached to the tractor and ploughed to a depth of 25 to 30 cm. Mouldboard ploughs are used where soil inversion is necessary. Victory plough is an animal drawn mouldboard plough with a short shaft. -

The Relationship Between Soil Properties and No-Tillage Agriculture" (1991)

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Soil Science News and Views Plant and Soil Sciences 1991 The Relationship Between Soil Properties and No- Tillage Agriculture Robert L. Blevins University of Kentucky Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits oy u. Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/pss_views Part of the Soil Science Commons Repository Citation Blevins, Robert L., "The Relationship Between Soil Properties and No-Tillage Agriculture" (1991). Soil Science News and Views. 38. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/pss_views/38 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Plant and Soil Sciences at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Soil Science News and Views by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE COOPERATIVE EXTENSION SERVICE Lexington, Kentucky 40546 Department of Agronomy ii i s Vol. 12, No. 2, 1991 The Relationship Between Soil Properties and No-Tillage Agricultural by Robert L. Blevins I am highly honored to be invited to present the 3rd annual S.H. Phillips Distinguished Lecture on No-Tillage Agriculture. My interest and subsequent research efforts in the area of no tillage agriculture began in 1969. Shirley Phillips encouraged my efforts through his interest and enthusiasm for this rather radical and new approach to farming without the use of tillage equipment. At that time, Harry Young, a western Kentucky farmer and pioneer of no-tillage agriculture along with Shirley, Jim Herron, Charlie Slack and other co-workers were excited about the potential of this new, innovative farming system and what it could do for the farmers of Kentucky. -

Seedbed and Planter Preparation

SoybeaniGrow BEST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES Chapter 11: Seedbed and Planter Preparation C. Gregg Carlson ([email protected]) Kurt Reitsma Obtaining a excellent soybean stand is a necessary step to successful soybean production. Preparing your land and planter for seeding is one of first steps required to optimize soybean yields (Fig. 11.1). Prior to seeding the field, planter maintenance should be completed and during planting the planter and seed placement should be routinely checked. We recommend that soybeans be planted at a depth of from 1 to 1.5 inches. In South Dakota soybean production, the soil temperature is critical and in South Dakota in the early spring, deeper is colder. Soybeans require a warmer soil (54°F) to germinate than corn (50°F). Colder means slower growth and less nutrient uptake. Soybeans are more sensitive to seeding depth than is corn. Studies in Northern climates have consistently shown that seeding soybeans below 2 to 2.5 inches typically results in a seedling population reduction of 20% or more from the number of seeds planted. The goal of this chapter is to provide guidance on seedbed and planter preparation. Seedbed and planter preparation requires planning and should be conducted at various times during the year. Figure 11.1. A John Deere DB120 Crop Planter. (Source: http://photo.machinestogo.net/main.php/v/user/equipment/john-deere-db120-crop-planter.jpg.html) 11-89 extension.sdstate.edu | © 2019, South Dakota Board of Regents Chilling injury Germination of soybean and corn seeds can be reduced by chilling injury. Chilling injury results from the seed uptaking cold water during germination. -

Surface and Subsurface Tillage Effects on Mine Soil Properties and Vegetative Response

Stephen F. Austin State University SFA ScholarWorks Faculty Publications Forestry 2018 Surface and Subsurface Tillage Effects on Mine Soil Properties and Vegetative Response H. Z. Angel Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture, Stephen F Austin State University Jeremy Stovall Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture, Stephen F Austin State University, [email protected] Hans Michael Williams Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture Division of Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Kenneth W. Farrish Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture, Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] Brian P. Oswald Arthur Temple College of Forestry and Agriculture, Stephen F. Austin State University, [email protected] SeeFollow next this page and for additional additional works authors at: https:/ /scholarworks.sfasu.edu/forestry Part of the Agronomy and Crop Sciences Commons, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Forest Sciences Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Repository Citation Angel, H. Z.; Stovall, Jeremy; Williams, Hans Michael; Farrish, Kenneth W.; Oswald, Brian P.; and Young, J. L., "Surface and Subsurface Tillage Effects on Mine Soil Properties and Vegetative Response" (2018). Faculty Publications. 499. https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/forestry/499 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Forestry at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors H. Z. Angel, Jeremy Stovall, Hans Michael Williams, Kenneth W. Farrish, Brian P. Oswald, and J. L. Young This article is available at SFA ScholarWorks: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/forestry/499 Published March 8, 2018 Forest, Range & Wildland Soils Surface and Subsurface Tillage Effects on Mine Soil Properties and Vegetative Response Soil compaction is an important concern for surface mine operations that H. -

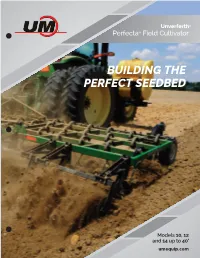

Building the Perfect Seedbed

Unverferth® Unverferth® Seedbed Tillage Perfecta® Field Cultivator Specifications Specifications Folding Perfecta Models 10, 12 and 14 Perfecta sizes for Bedded Crops Cat. 2 Std. and Quick, Cat. 3 Std. and Quick, Cat. 3 Narrow Quick 10'–28' Cat. 2 Std. and Quick, Cat. 3 Std. and Quick, Cat. 3 Narrow Quick; 7' accepts Cat. 1 Std. and Opt. Quick Hitch (optional adapter pins required) 18' Base with Folding Wings — Single Basket S-Tines Shovels BUILDING THE Bed Rolling Approx. Weight Number of Description Overall Working Transport Transport Number of Rollers, Width Number Approx. Width Baskets (lbs.) Leveling Bar Qty. Size Qty. Size Width S-Tine Width Width Height* S-Tines Weight (lbs.) 4' 5' 6' Teeth 6 30" Adj. 6 10" 40' 39'6" 18'4" 12'2" 79 — 2 5 81 7,060 66" 28' for 5 - 66" Beds — Folding 20 19.5" 20 2.75" 5 - 4 ft. 2,745 PERFECT SEEDBED 39' 37'6" 18'4" 11'4" 75 — 4 3 78 6,615 40 16" 40 1" 37' 35'6" 18'4" 10'7" 71 2 2 3 73 6,250 6 30" Adj. 6 10" 60" 25' for 5 - 60" Beds — Folding 20 19.5" 20 2.75" 5 - 4 ft. 3,365 15' Base with Folding Wings — Single Basket 40 16" 40 1" 34' 33'6" 15'7" 11'3" 67 1 6 — 68 6,250 4 30" Adj. 4 10" 84" 22' for 3 - 84" Beds — Folding 6 19.5" 6 2.75" 3 - 6 ft. 2,720 32' 31'6" 15'7" 10'5" 63 3 4 — 64 5,960 30 16" 30 1" 30' 29'6" 15'7" 9'8" 59 5 2 — 60 5,570 4 30" Adj. -

No-Till: the Quiet Revolution

AGRICULTURE No-Till: the Quiet Revolution The age-old practice of turning the soil before planting a new crop is a leading cause of farmland degradation. Many farmers are thus looking to make plowing a thing of the past By David R. Huggins and John P. Reganold © 2008 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, INC. 70 SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN July 2008 ohn Aeschliman turns over a shovelful of topsoil on his 4,000-acre farm in the Palouse Jregion of eastern Washington State. The black earth crumbles easily, revealing a porous structure and an abundance of organic matter that facilitate root growth. Loads of earthworms are visible, too—another healthy sign. Thirty-four years ago only a few earthworms, if any, could be found in a spadeful of his soil. Back then, Aeschliman would plow the fields before each planting, burying the residues from the previous crop and readying the ground for the next one. The hilly Palouse region had been farmed that way for decades. But the tillage was taking a toll on the Palouse, and its famously fertile soil was eroding at an alarming rate. Convinced that there had to be a better way to work the land, Aeschliman decided to experi- ment in 1974 with an emerging method known as no-till farming. Most farmers worldwide plow their land in preparation for sowing crops. The practice of turning the soil before planting buries crop resi- dues, animal manure and troublesome weeds and also aerates and warms the soil. But clear- ing and disturbing the soil in this way can also leave it vulnerable to erosion by wind and water. -

Conservation Tillage Cultivators for No-Till and Ridge-Till

Conservation Tillage Cultivators for No-till and Ridge-till Although no-till implies “no tillage,” many producers Ridge-till Equipment using high residue cropping systems allow themselves the In addition to handling high amounts of residue, the fl exibility of row crop cultivation. The protective surface ridge cultivator must be capable of throwing soil up into residue is disturbed only when the plant canopy is rapidly a ridge. Adjustable ridging wings or disk hillers often are beginning to protect the area between rows. Weed escapes used for this purpose. can be controlled with timely cultivation. The amount of soil being thrown as well as its speed and When changing equipment, producers with highly erod- angular direction from the line of travel affect ridge height. ible land should strongly consider a cultivator capable of Deeper, faster cultivation with ridging wings or disk hillers handling high amounts of residue. Ridge-till producers angled outward from the line of travel all contribute to usually cultivate twice, once early and once to reform more soil being thrown into the ridge area. Maximum ridges. Many no-till producers cultivate only as needed fi nal ridge height is limited by the maximum angle at but appreciate having the option for additional cultivation. which the soil will rest (angle of repose) and row width. Ridge-till systems require mechanical cultivation. Banding Shields (such as sheet metal, disks, or spider wheels) pesticides limits chemical costs and helps environmental are used during the fi rst cultivation. Deeper cultivation quality, but makes timely, effective cultivation more critical. during the fi rst pass helps supply loose soil for later ridge building. -

Garden and Field Tillage and Cultivation

1.2 Garden and Field Tillage and Cultivation Introduction 33 Lecture 1: Overview of Tillage and Cultivation 35 Lecture 2: French Intensive Method of Soil Cultivation 41 Lecture 3: Mechanical Field-Scale Tillage and Cultivation 43 Demonstration 1: Preparing the Garden Site for French-Intensive Soil Cultivation Instructor’s Demonstration Outline 45 Students’ Step-by-Step Instructions 49 Demonstration 2: French-Intensive Soil Cultivation Instructor’s Demonstration Outline 53 Students’ Step-by-Step Instructions 57 Hands-on Exercise 61 Demonstration 3: Mechanical Tillage and Cultivation 63 Assessment Questions and Key 65 Resources 68 Supplements 1. Goals of Soil Cultivation 69 2. Origins of the French-Intensive Method 72 3. Tillage and Bed Formation Sequences for 74 the Small Farm 4. Field-Scale Row Spacing 76 Glossary 79 Appendices 1. Estimating Soil Moisture by Feel 80 2. Garden-Scale Tillage and Planting Implements 82 3. French Intensive/Double-Digging Sequence 83 4. Side Forking or Deep Digging Sequence 86 5. Field-Scale Tillage and Planting Implements 89 6. Tractors and Implements for Mixed Vegetable 93 Farming Operations Based on Acreage 7. Tillage Pattern for Offset Wheel Disc 94 Part 1 – 32 | Unit 1.2 Tillage & Cultivation Introduction: Soil Tillage & Cultivation UNIT OVERVIEW MODES OF INSTRUCTION Cultivation is a purposefully broader > LECTURES (3 LECTURES, 1–1.5 HOURS EACH) concept than simply digging or tilling Lecture 1 covers the definition of cultivation and tillage, the the soil—cultivation involves an general aims of soil cultivation, the factors influencing culti- vation approaches, and the potential impacts of excessive or array of tools, materials and methods ill-timed tillage. -

Pursuing Conservation Tillage Systems for Organic Crop Production

ATTRA's ORGANIC MATTERS SERIES PURSUING CONSERVATION TILLAGE SYSTEMS FOR ORGANIC CROP PRODUCTION By George Kuepper, NCAT Agriculture Specialist, June 2001 Contents: Introduction ............................................................................................................................2 Organic Farming & the Tillage Dilemma .........................................................................3 Mulch Tillage .........................................................................................................................5 Ridge Tillage ..........................................................................................................................5 Killed Mulch Systems ..........................................................................................................6 Mowing ..................................................................................................................6 Undercutting .........................................................................................................7 Rolling & Roll-Chopping ..................................................................................8 Weather-Kill .........................................................................................................8 Cover Crops for Killed Mulch Systems ..........................................................9 The Challenges of Killed Mulches ...................................................................9 Resources & Research on Killed Mulches ......................................................10 -

Using Strip Tillage in Vegetable Production Systems in Western Oregon

EM 8824 • February 2003 $2.50 Using Strip Tillage in Vegetable Production Systems in Western Oregon John Luna and Mary Staben What is strip tillage? Strip tillage is a form of conser- vation tillage that involves tilling narrow strips for crop establishment while leaving areas between the strips with undisturbed crop residue (Figure 1). Strip tillage can reduce soil erosion and soil compaction, as well as machinery, fuel, and labor costs. Combined with winter cover crops, strip tillage also can dramati- cally improve soil quality. Strip tillage combines some of the advantages of full-width, traditional tillage with those of no-till (direct- seeding) systems. Unlike no-till, however, where the seed is planted Figure 1.—A strip-till system uses killed cover crops or crop residue into narrow slits in the soil, strip till- as surface mulch. Standard planting equipment is used to plant into age involves tilling a 6- to 12-inch- the tilled strips. wide band, usually 8 to 16 inches deep. Traditional planters then are used to plant into Oregon research in strip tillage the tilled strips. On-farm research was conducted in the Willamette Strip tillage involves the substitution of strip-till Valley from 1996 to 2001 to compare strip tillage equipment for conventional tillage equipment. It with conventional tillage systems. More than 30 involves changing several cultural practices for large-scale field trials were conducted on a variety optimum results. of soils and with different crop rotations. Trials were conducted primarily on sweet corn, but other veg- etable crops were investigated as well. Commercial John Luna, associate professor of horticulture, and Mary Staben, nutrient management educator, Oregon State University harvesting equipment was used.