Privacy at Speed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lean and Mean India Armed Forces Order New Light-Attack Chopper Developed by HAL

MOBILITY ENGINEERINGTM ENGLISH QUARTERLY Vol : 5 Issue : 1 January - March 2018 Free Distribution Lean and mean India armed forces order new light-attack chopper developed by HAL HCCI Hands-off engines driving is here Overcoming Cadillac’s Super Cruise, the challenges autonomous-vehicle tech overview ME Altair Ad 0318.qxp_Mobility FP 1/5/18 2:58 PM Page 1 CONTENTS Features 33 Advancing toward driverless cars 46 Electrification not a one-size- AUTOMOTIVE AUTONOMY fits-all solution OFF-HIGHWAY Autonomous-driving technology is set to revolutionize the ELECTRIFICATION auto industry. But getting to a true “driverless” future will Efforts in the off-highway industry have been under way be an iterative process based on merging numerous for decades, but electrification technology still faces individual innovations. implementation challenges. 36 Overcoming the challenges of 50 700 miles, hands-free! HCCI combustion AUTOMOTIVE ADAS AUTOMOTIVE PROPULSION GM’s Super Cruise turns Cadillac drivers into passengers in a Homogenous-charge compression ignition (HCCI) holds well-engineered first step toward greater vehicle autonomy. considerable promise to unlock new IC-engine efficiencies. But HCCI’s advantages bring engineering obstacles, particularly emissions control. 40 Simulation for tractor cabin vibroacoustic optimization OFF-HIGHWAY SIMULATION Cover The Indian Army and Air Foce recently ordered more than a 43 Method of identifying and dozen copies of the new Light stopping an electronically Combat Helicopter (LCH) controlled diesel engine in developed -

Lexus History 1989-2019

LEXUS HISTORY BRAND CARS INNOVATIONS 1983 August 1983. At a secret meeting More than 400 prototype Over 1,400 engineers and 2,300 in Japan, Toyota’s Chairman Dr vehicles are built, 100 are crash technicians rise to Toyoda-san’s Eiji Toyoda sets a challenge to a tested and more than 4.3 million challenge. team of strategists, engineers and test kilometres are driven in Japan, designers: “Can we create a the USA and Europe. Sixty designers, 24 engineering luxury car to challenge the very teams, and 220 support workers best?” are engaged on the “F1” project. Every detail was exhaustively thought through – build tolerances were at least twice as accurate as competitors. 1987 In May 1987, four years of development time and many full- sized clay models later, Lexus executives sign off on the final LS design. 1988 The brand name ‘Lexus’ is chosen to represent luxury and high-end technology. (Early suggestions included Alexis and Lexis.) 1989 The Lexus brand is born The first LS 400 is launched, At the Lexus Tahara plant in incorporating hundreds of new Japan, the welding process for the patents and setting new standards LS 400 is fully automated, making for quality and value. Almost welds 1.5 times stronger than 3,000 are sold in the first month those on conventionally welded after launch. vehicles. 1990 Lexus is launched in Europe with a On the LS 400, aerodynamic single model range: the LS 400. considerations lead to the underside of the vehicle having a smooth floorpan and a number of special fairings to direct airflow. -

DESIGN and IMPLEMENTATION of DRIVER DROWSINESS DETECTION SYSTEM by Aleksandar Colic

DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION OF DRIVER DROWSINESS DETECTION SYSTEM by Aleksandar Colic A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Engineering & Computer Science in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL December 2014 Copyright 2014 by Aleksandar Colic ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Dr. Oge Marques for his support, guidance and encouragement throughout my graduate studies. I also wish to thank my committee: Dr. Borko Furht, Dr. Robert B. Cooper and Dr. Shihong Huang for their invaluable suggestions. I am deeply thankful to Jean Mangiaracina from Graduate Programs for her immeasurable help on this long journey. And last but not least my many thanks go to my family for always believing in me and friends and colleagues for always being there for me. iv ABSTRACT Author: Aleksandar Colic Title: Design and Implementation of Driver Drowsiness Detection System Institution: Florida Atlantic University Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Oge Marques Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Year: 2014 There is a substantial amount of evidence that suggests that driver drowsiness plays a significant role in road accidents. Alarming recent statistics are raising the interest in equipping vehicles with driver drowsiness detection systems. This disserta- tion describes the design and implementation of a driver drowsiness detection system that is based on the analysis of visual input consisting of the driver's face and eyes. The resulting system combines off-the-shelf software components for face detection, human skin color detection and eye state classification in a novel way. -

671Eabc00a0e0acc09ed5272cb

2017 LEXUS BEGINNINGS A NEW IDEA IS BORN Before Lexus, cars tended to be one thing or another. Some delivered performance, but not comfort; safety, but not style. With the 1990 release of the LS 400, Lexus introduced itself as a challenger to the status quo, bringing luxury, performance, and technology together for the first time. Over the quarter-century of relentless innovation that followed, Lexus has written a story that is truly amazing. The first LS 400s rolled off ships in the summer of 1989. BEGINNINGS LEXUS ‘YET’ PHILOSOPHY Opposites in harmony. This idea is the heart of the Lexus ‘Yet’ Philosophy, one of our guiding principles since we introduced the very first LS 400. It is why you are able to experience an exhilarating, powerful drive, yet with exceptional fuel efficiency. It is the epitome of luxury, yet with equally high environmental standards. It means surrounding you with the most advanced, yet elegantly intuitive, technology. LEXUS EXPERIENCE OMOTENASHI Anyone can deliver customer service. But only Lexus delivers omotenashi—the Japanese word for hospitality. More than simply fulfilling your requests, at the heart of omotenashi is anticipating your needs in advance and delivering service so exceptional it becomes an unexpected pleasure. This higher level of attention comes from an insightful understanding of your individual wants and needs, and a commitment to treating every customer as nothing less than a guest in our home. Like every car we build, we apply the same unrivalled standard to customer care. DESIGN LEXUS SIGNATURE L-FINESSE The new, yet already iconic, Lexus spindle grille The philosophy of ‘Yet’ is also at the heart boldly commands attention with its aggressive of the Lexus design philosophy, L-Finesse. -

Automotive DMS (Driver Monitoring System) Research Report, 2019-2020

Automotive DMS (Driver Monitoring System) Research Report, 2019-2020 June 2020 STUDY GOAL AND OBJECTIVES METHODOLOGY This report provides the industry executives with strategically significant Both primary and secondary research methodologies were used competitor information, analysis, insight and projection on the in preparing this study. Initially, a comprehensive and exhaustive competitive pattern and key companies in the industry, crucial to the search of the literature on this industry was conducted. These development and implementation of effective business, marketing and sources included related books and journals, trade literature, R&D programs. marketing literature, other product/promotional literature, annual reports, security analyst reports, and other publications. REPORT OBJECTIVES Subsequently, telephone interviews or email correspondence To establish a comprehensive, factual, annually updated and cost- was conducted with marketing executives etc. Other sources effective information base on market size, competition patterns, included related magazines, academics, and consulting market segments, goals and strategies of the leading players in the companies. market, reviews and forecasts. To assist potential market entrants in evaluating prospective INFORMATION SOURCES acquisition and joint venture candidates. The primary information sources include Company Reports, To complement the organizations’ internal competitor information and National Bureau of Statistics of China etc. gathering efforts with strategic analysis, data -

Lexus GS (2015) UK

ffers View View O / XXX 02 GS / AMAZING IN MOTION / 03 / AMAZING IN MOTION GS Video Watch Watch the AMAZING IN MOTION Developing the GS involved a relentless search to make it better in every way. Built at the world’s most award-winning plant, the GS resets benchmarks for comfort, craftsmanship and advanced technology. Inside, on selected grades, there’s the largest navigation screen ever fitted to a Lexus, award-winning nanoe® air conditioning (on Premier grade) and Find a Dealer innovative driver support systems. Paintwork is sanded by hand, with single-source wood and solid aluminium used for trims and detailing. To make the GS an incredibly enjoyable car to drive, prototypes were tested over one million miles, demonstrating that we really don’t stop until we create amazing. LEXUS PAINT IS DEVELOPED TO OPTIMISE Book Drive a Test APPEARANCE WITH THE WEATHER Book Find Watch View a Test Drive a Dealer the Video Offers GS / NEW LOOK / 04 noise insidethecabin. wind andreducing drivingstability increasing aerodynamics, with lights fins ontherear contribute tothecar’sclass-leading GS grille ontheradiator closable vents of the andautomatic Smooth underbodycovers dynamichandling. hintatsuperb, wheel arches grille’.Extended ‘spindle its purposefulfront look,thefocalpointbeing new atotally the GS given have ourdesigners scratch, Starting from WITH ARRIVE PRESENCE ffers View View O / XXX 06 GS / ENGINEERING 07 GS Video Watch Watch the ENGINEERED FOR ENJOYMENT You’ll enjoy sharp, accurate steering and excellent control when cornering in the GS. On the motorway, you’ll notice world-class Find a Dealer stability and ride comfort at high speeds. For a more refined and precise drive, the chassis is now stiffer and has been totally re-engineered. -

MADD Response NHTSA

MOTHERS AGAINST DRUNK DRIVING Updated Report: Advanced Drunk Driving Prevention Technologies Driving performance monitoring, driver monitoring and passive alcohol detection technology can eliminate drunk, drugged, and other forms of impaired driving. NO MORE VICTIMS: Technologies to eliminate drunk driving, and other forms of driver impairment, are ready for the road May 12, 2021 Edition Two DOT Docket No. NHTSA-2020-0102 Docket Management Facility U.S. Department of Transportation West Building Ground Floor Room W12-140 1200 New Jersey Avenue, S.E. Washington, D.C. 20590-0001 Filed via www.regulations.gov Impaired Driving Technologies Request for Information 85 Federal Register 71987, November 12, 2020 1 Letter from MADD National President Alex Otte In 2019, 10,142 people were killed in alcohol-related traffic crashes, and hundreds of thousands more were seriously injured. According to preliminary data from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), for the first nine months of 2020, traffic fatalities increased by 5 percent even though the number of vehicle miles traveled decreased by 15 percent. (NHTSA, 2020). This tragic increase in roadway fatalities is one of the biggest hikes in a generation, and it shows the fight against impaired driving is far from over. On January 11, 2021, Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) submitted information on 187 impaired driving vehicle safety technologies as a result of a Request for Information (RFI) by NHTSA. The request from NHTSA was for information from these four areas: • (1) -

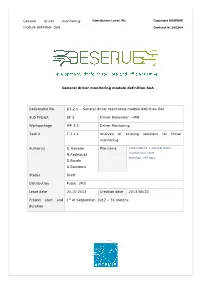

General Driver Monitoring Module Definition Soa

General driver monitoring Distribution Level: PU Copyright DESERVE module definition SoA Contract N. 295364 General driver monitoring module definition SoA Deliverable No. D3.2.1 – General driver monitoring module definition SoA Sub Project SP 3 Driver Behaviour - HMI Workpackage WP 3.2 Driver Monitoring Task n. T 3.2.1 Analysis of existing solutions for Driver monitoring Author(s) S. Boverie File name Deliverable32_1 General driver monitoring module N.Rodriguez definition_v09.docx D.Bande A.Saccagno Status Draft Distribution Public (PU) Issue date 24 .10.2013 Creation date 2013/05/23 Project start and 1st of September, 2012 – 36 months duration General driver monitoring Distribution Level: PU Copyright DESERVE module definition SoA Contract N. 295364 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................. 2 LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................. 3 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................... 4 REVISION CHART AND HISTORY LOG ....................................................................... 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 8 MEASURES FOR DROWSINESS DETECTION .............................................................. 10 MEASURES -

Specifications GS 2015 October 23, 2014

Specifications GS 2015 October 23, 2014 GS 350 AWD GS 450h Interior Steering Heated Steering Wheel • • Steering Wheel Audio Controls • Leather Wrapped Steering Wheel • • Steering Wheel Paddle Shifters (A/T) • • Heated Wood Steering Wheel • Climate Control Dual Zone Automatic Climate Control • Cabin Air Filter • Rear Seat Heater Ducts • Dual Zone Climate Control • Front Auto Climate Control • Audio Video: 12.3-inch Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) display • • 12 Speaker Lexus Premium Audio • • Audio Auxiliary Input Jack • • USB Audio Input • • Bluetooth Capability • • Integrated SiriusXM Satellite Radio • 17 Speaker Mark Levinson Premium Audio System • XM Satellite Radio (Factory Installed) • Seats Leather Seat Surfaces • • Heated and Air Conditioned Front Seats • 10-way Power Adjustable Drivers Seat • • Driver Seat Memory • • 1 GS 350 AWD GS 450h 10-way Power Adjustable Passenger Seat • • Driver Seat Adjustments: 18-way Power Driver Seat • Adjustments Passenger Seat Adjustments: 18-way Power • Adjustable Passenger Seat Premium Leather Seat Surfaces • Passenger Seat Memory • Heated Rear Seats • Heated & Ventilated Front Seats • Windows Power Windows with Auto Up/Down for All Windows • • Side Window Defoggers • Electric Rear Window Defroster • • UV Glass Protection • • Convenience Power Door Locks • Instrumentation Backup Camera • • Tachometer • Dual Trip Odometer • Water Temperature Gauge • • Outside Temperature Gauge • Multi-function Display • Instrumentation: Navigation System • • Instrumentation: Remote Touch Interface • Head-Up Display -

CONSUMER REPORTS NEW CARS (ISSN 1530-3267) Is Published by Whether You’Re Buying Or Test Center Team Consumer Reports, Inc., 101 Truman Ave., Yonkers, NY 10703

SMART PICKS UNDER $30,000 < 2019 SUBARU CROSSTREK TM 248 Models New Cars Rated 2019 TOYOTA BEST RAV4 SUVS COMPACT SUVs Worth Buying GET TOP $$$ TRUCKS For Your Trade-In STANDOUT TIRES From Our Tests CARS JULY 2019 CR.ORG A NEW EV CHALLENGER TO TESLA Please display until July 15, 2019 Contents JULY 2019 Honda CR-V Versatile, efficient, and affordable, it’s just one of the top-rated compact SUVs we tested. P. 22 3 Ask Our Experts We answer your questions about car rentals. STARTING UP 4 Get Top Dollar for Your Used Car Should you sell your old car or trade it in? CR’s experts prepare you for the dealership with money-saving strategies. ON THE ROAD 12 New Models for 2020 Our fi rst impressions of the P. 20 Cadillac XT6, Ford Explorer, Hyundai Palisade, Subaru Legacy, and Toyota Supra. 16 At the Track We drive Jaguar’s new I-Pace EV, the redesigned Audi A6 and Volvo S60, and two new SUVs with familiar names. 22 The Best Compact SUVs We rate the new 2019 Toyota RAV4 against popular competitors from Subaru, Mazda, and Honda. RATINGS 30 New Cars Under $30K From subcompacts to minivans, we pick the best—and off er P. 34 P. 30 used-car alternatives. RATINGS RATINGS & REFERENCE FOLLOW CONSUMER REPORTS' EXPERTS 184 Road-Test Highlights FACEBOOK Performance data from our fb.com/ consumerreportscars test-track program. Lexus RX 350L YOUTUBE 190 Safety Features and /consumerreports Crash-Test Ratings Top Tires 34 46 Vehicle Ratings Important information for INSTAGRAM We help you choose the We rank all of the vehicles each model in this issue. -

Consumer Reports Auto Industry Insights: ADAS Lane Systems

Consumer Reports Auto Industry Insights: ADAS Lane Systems May 2021 © 2021 Consumer Reports, Inc. CANNOT BE REPRINTED WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION OF CONSUMER REPORTS About This Report Consumer Reports continually reviews new technology and uses several inputs to evaluate the design and implementation of these new systems. As part of CR’s efforts to shape the marketplace in favor of consumers, this report has been written for the industry to share our latest consumer-driven data and expert insights about lane systems. The 2020 ADAS Survey of CR members was conducted from October to December 2020. Responses were collected from owners of 56,900-plus vehicles from model years 2017 to 2021. All survey participants were required to have used ADAS features in their vehicles. Only vehicles that are known to have ADAS were chosen for inclusion in the survey data analysis. Data points have to meet a minimum sample size threshold of 50 responses to be included in this analysis. Is the survey data available? Data is available for licensing through the CR Data Intelligence program. Please direct inquiries to [email protected]. © 2021 Consumer Reports, Inc. CANNOT BE REPRINTED WITHOUT WRITTEN PERMISSION OF CONSUMER REPORTS 2 ADAS Terms & Definitions • AEB (automatic emergency braking): Detects potential collisions with a vehicle ahead, provides forward collision warning, and automatically brakes to avoid a collision or lessen the severity of impact. Some systems also detect pedestrians or other objects. • Backup Camera: Displays the area behind the vehicle when in Reverse gear. • BSW (blind spot warning): Detects vehicles in the blind spot while driving and notifies the driver of their presence. -

Lexus History 1983 1989 1990

LEXUS HISTORY 1983 1989 1990 BRAND BRAND BRAND August 1983. At a secret meeting in Japan, Toyota’s The Lexus brand is born. Lexus is launched in Europe with a single model range, Chairman Dr Eiji Toyoda sets a challenge to a team the LS 400. of strategists, engineers and designers: “Can we create a luxury car to challenge the very best?” CARS The first LS 400 is launched, incorporating INNOVATIONS hundreds of new patents and setting new standards On the LS 400, aerodynamic considerations led to the CARS for quality and value. 2,919 are sold in the first underside of the vehicle having a smooth floor pan and More than 400 prototype vehicles are built, 100 month after launch. a number of special fairings to direct airflow away from are crash tested and more than 4.3 million test components. This gave the LS 400 class-leading under kilometres are driven in Japan, the USA and Europe body aerodynamics. INNOVATIONS At the Lexus Tahara plant the welding process for the INNOVATIONS LS 400 was totally automated making welds 1.5 times More than 1,400 engineers and 2,300 technicians rise stronger than those on conventionally welded vehicles. to the challenge. 60 designers, 24 engineering teams, and 220 support workers are engaged in the “F1” project. Every detail was exhaustively thought through – build tolerances were at least twice as accurate as competitors. 1991 1993 1995 1997 BRAND CARS CARS BRAND Lexus starts its dominance in JD Power The new Lexus GS 300 was The second generation LS 400 A V8 4-litre engine with VVT-i was used customer satisfaction surveys in USA, launched in Europe at the was launched.