“Potatoe” Kings Why Vice Presidents Are Doomed from the Start

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monica Prasad Northwestern University Department of Sociology

SPRING 2016 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW COLLOQUIUM ON TAX POLICY AND PUBLIC FINANCE “The Popular Origins of Neoliberalism in the Reagan Tax Cut of 1981” Monica Prasad Northwestern University Department of Sociology May 3, 2016 Vanderbilt-208 Time: 4:00-5:50 pm Number 14 SCHEDULE FOR 2016 NYU TAX POLICY COLLOQUIUM (All sessions meet on Tuesdays from 4-5:50 pm in Vanderbilt 208, NYU Law School) 1. January 19 – Eric Talley, Columbia Law School. “Corporate Inversions and the unbundling of Regulatory Competition.” 2. January 26 – Michael Simkovic, Seton Hall Law School. “The Knowledge Tax.” 3. February 2 – Lucy Martin, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Political Science. “The Structure of American Income Tax Policy Preferences.” 4. February 9 – Donald Marron, Urban Institute. “Should Governments Tax Unhealthy Foods and Drinks?" 5. February 23 – Reuven S. Avi-Yonah, University of Michigan Law School. “Evaluating BEPS” 6. March 1 – Kevin Markle, University of Iowa Business School. “The Effect of Financial Constraints on Income Shifting by U.S. Multinationals.” 7. March 8 – Theodore P. Seto, Loyola Law School, Los Angeles. “Preference-Shifting and the Non-Falsifiability of Optimal Tax Theory.” 8. March 22 – James Kwak, University of Connecticut School of Law. “Reducing Inequality With a Retrospective Tax on Capital.” 9. March 29 – Miranda Stewart, The Australian National University. “Transnational Tax Law: Fiction or Reality, Future or Now?” 10. April 5 – Richard Prisinzano, U.S. Treasury Department, and Danny Yagan, University of California at Berkeley Economics Department, et al. “Business In The United States: Who Owns It And How Much Tax Do They Pay?” 11. -

Presidential Recordings of Lyndon B. Johnson (November 22, 1963-January 10, 1969) Added to the National Registry: 2013 Essay by Bruce J

Presidential Recordings of Lyndon B. Johnson (November 22, 1963-January 10, 1969) Added to the National Registry: 2013 Essay by Bruce J. Schulman (guest post)* Lyndon B. Johnson built his career--and became one of the nation’s most effective Senate leaders--through his mastery of face-to-face contact. Applying his famous “Treatment,” LBJ pleased, cajoled, flattered, teased, and threatened colleagues and rivals. He would grab people by the lapels, speak right into their faces, and convince them they had always wanted to vote the way Johnson insisted. He could share whiskey and off-color stories with some colleagues, hold detailed policy discussions with others, toast their successes, and mourn their losses. Syndicated newspaper columnists Rowland Evans and Robert Novak vividly described the Johnson Treatment as: supplication, accusation, cajolery, exuberance, scorn, tears, complaint, the hint of threat. It was all of these together. Its velocity was breathtaking, and it was all in one direction. Interjections from the target were rare. Johnson anticipated them before they could be spoken. He moved in close, his face a scant millimeter from his target, his eyes widening and narrowing, his eyebrows rising and falling. 1 While President Johnson never abandoned in-person persuasion, the scheduling and security demands of the White House forced him to rely more heavily on indirect forms of communication. Like Muddy Waters plugging in his electric guitar or Laurel and Hardy making the transition from silent film to talkies, LBJ became maestro of the telephone. He had the Army Signal Corps install scores of special POTUS lines (an acronym for “President of the United States”) so that he could communicate instantly with officials around the government. -

Election Division Presidential Electors Faqs and Roster of Electors, 1816

Election Division Presidential Electors FAQ Q1: How many presidential electors does Indiana have? What determines this number? Indiana currently has 11 presidential electors. Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution of the United States provides that each state shall appoint a number of electors equal to the number of Senators or Representatives to which the state is entitled in Congress. Since Indiana has currently has 9 U.S. Representatives and 2 U.S. Senators, the state is entitled to 11 electors. Q2: What are the requirements to serve as a presidential elector in Indiana? The requirements are set forth in the Constitution of the United States. Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2 provides that "no Senator or Representative, or person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector." Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment also states that "No person shall be... elector of President or Vice-President... who, having previously taken an oath... to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. Congress may be a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability." These requirements are included in state law at Indiana Code 3-8-1-6(b). Q3: How does a person become a candidate to be chosen as a presidential elector in Indiana? Three political parties (Democratic, Libertarian, and Republican) have their presidential and vice- presidential candidates placed on Indiana ballots after their party's national convention. -

Federal Files on the Famous–And Infamous

Federal Files on the Famous–and Infamous The collections of personnel records at the National Archives available. Digital copies of PEPs can be purchased on CD/DVDs. include files that document military and civilian service for The price of the disc depends on the number of pages contained persons who are well known to the public for many reasons. in the original paper record and range from $20 (100 pages or These individuals include celebrated military leaders, less) to $250 (more than 1,800 pages). For more information or Medal of Honor recipients, U.S. Presidents, members of to order copies of digitized PEP records only, please write to pep. Congress, other government officials, scientists, artists, [email protected]. Archival staff are in the process of identifying entertainers, and sports figures—individuals noted for the records of prominent civilian employees whose names will personal accomplishments as well as persons known for their be added to the list. Other individuals whose records are now infamous activities. available for purchase on CD are: The military service departments and NARA have Creighton W. Abrams, Grover Cleveland Alexander, identified over 500 such military records for individuals Desi Arnaz, Joe L. Barrow, John M. Birch, Hugo L. Black, referred to as “Persons of Exceptional Prominence” (PEP). Gregory Boyington, Prescott S. Bush, Smedley Butler, Evans Many of these records are now open to the public earlier F. Carlson, William A. Carter, Adna R. Chaffee, Claire than they otherwise would have been (62 years after the Chennault, Mark W. Clark, Benjamin O. Davis. separation dates) as the result of a special agreement that Also, George Dewey, William Donovan, James H. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Voting Without Choosing?

Institute of African Studies Carleton University (Ottawa, Canada) 2019 (7) Voting without Choosing? Ethnic Voting Behaviour and Voting Patterns in Nigeria’s 2015 Presidential Election and Implications for Institutionalisation of Social Conflicts Kialee Nyiayaana1 Abstract: Nigeria’s 2015 Presidential Election was widely seen as competitive, fair and less violent than other elections since the transition to democracy in 1999. This paper does not argue otherwise. Rather, it problematizes ethnic voting behaviour and voting patterns observed in the election and raises questions about their implications for institutionalisation of democracy and social conflicts in Nigeria. It argues that while scholarly examinations portray the presidential election results as ‘victory for democracy’, not least because an incumbent president was defeated for the first time in Nigeria, analysis of the spatial structure of votes cast reveals a predominant pattern of voting along ethnic, religious and geospatial lines. It further contends that this identity-based voting not only translates into a phenomenon of ‘voting without choosing,’ but is also problematic for social cohesion, interethnic harmony and peacebuilding in Nigeria. The relaxation of agitations for resource control in the Niger Delta throughout President Jonathan’s tenure and its revival in post-Jonathan regime is illustrative of the dilemmas and contradictions of ethnic voting and voting without choosing in Nigeria. This observation draws policy attention to addressing structural underpinnings of the relationship between ethnicity, geography and voting behaviour in Nigerian politics so as to consolidate democratic gains and enhance democratic peace in Nigeria. Nigeria’s 2015 Presidential election has been described as a turning point in the country’s political history and democratic evolution. -

The Misrepresented Road to Madame President: Media Coverage of Female Candidates for National Office

THE MISREPRESENTED ROAD TO MADAME PRESIDENT: MEDIA COVERAGE OF FEMALE CANDIDATES FOR NATIONAL OFFICE by Jessica Pinckney A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Government Baltimore, Maryland May, 2015 © 2015 Jessica Pinckney All Rights Reserved Abstract While women represent over fifty percent of the U.S. population, it is blatantly clear that they are not as equally represented in leadership positions in the government and in private institutions. Despite their representation throughout the nation, women only make up twenty percent of the House and Senate. That is far from a representative number and something that really hurts our society as a whole. While these inequalities exist, they are perpetuated by the world in which we live, where the media plays a heavy role in molding peoples’ opinions, both consciously and subconsciously. The way in which the media presents news about women is not always representative of the women themselves and influences public opinion a great deal, which can also affect women’s ability to rise to the top, thereby breaking the ultimate glass ceilings. This research looks at a number of cases in which female politicians ran for and/or were elected to political positions at the national level (President, Vice President, and Congress) and seeks to look at the progress, or lack thereof, in media’s portrayal of female candidates running for office. The overarching goal of the research is to simply show examples of biased and unbiased coverage and address the negative or positive ways in which that coverage influences the candidate. -

Brazil Ahead of the 2018 Elections

BRIEFING Brazil ahead of the 2018 elections SUMMARY On 7 October 2018, about 147 million Brazilians will go to the polls to choose a new president, new governors and new members of the bicameral National Congress and state legislatures. If, as expected, none of the presidential candidates gains over 50 % of votes, a run-off between the two best-performing presidential candidates is scheduled to take place on 28 October 2018. Brazil's severe and protracted political, economic, social and public-security crisis has created a complex and polarised political climate that makes the election outcome highly unpredictable. Pollsters show that voters have lost faith in a discredited political elite and that only anti- establishment outsiders not embroiled in large-scale corruption scandals and entrenched clientelism would truly match voters' preferences. However, there is a huge gap between voters' strong demand for a radical political renewal based on new faces, and the dramatic shortage of political newcomers among the candidates. Voters' disillusionment with conventional politics and political institutions has fuelled nostalgic preferences and is likely to prompt part of the electorate to shift away from centrist candidates associated with policy continuity to candidates at the opposite sides of the party spectrum. Many less well-off voters would have welcomed a return to office of former left-wing President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (2003-2010), who due to a then booming economy, could run social programmes that lifted millions out of extreme poverty and who, barred by Brazil's judiciary from running in 2018, has tried to transfer his high popularity to his much less-known replacement. -

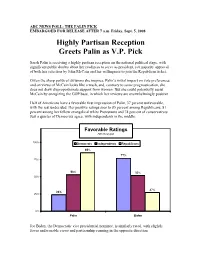

Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin As V.P. Pick

ABC NEWS POLL: THE PALIN PICK EMBARGOED FOR RELEASE AFTER 7 a.m. Friday, Sept. 5, 2008 Highly Partisan Reception Greets Palin as V.P. Pick Sarah Palin is receiving a highly partisan reception on the national political stage, with significant public doubts about her readiness to serve as president, yet majority approval of both her selection by John McCain and her willingness to join the Republican ticket. Given the sharp political divisions she inspires, Palin’s initial impact on vote preferences and on views of McCain looks like a wash, and, contrary to some prognostication, she does not draw disproportionate support from women. But she could potentially assist McCain by energizing the GOP base, in which her reviews are overwhelmingly positive. Half of Americans have a favorable first impression of Palin, 37 percent unfavorable, with the rest undecided. Her positive ratings soar to 85 percent among Republicans, 81 percent among her fellow evangelical white Protestants and 74 percent of conservatives. Just a quarter of Democrats agree, with independents in the middle. Favorable Ratings ABC News poll 100% Democrats Independents Republicans 85% 77% 75% 53% 52% 50% 27% 24% 25% 0% Palin Biden Joe Biden, the Democratic vice presidential nominee, is similarly rated, with slightly fewer unfavorable views and partisanship running in the opposite direction. Palin: Biden: Favorable Unfavorable Favorable Unfavorable All 50% 37 54% 30 Democrats 24 63 77 9 Independents 53 34 52 31 Republicans 85 7 27 60 Men 54 37 55 35 Women 47 36 54 27 IMPACT – The public by a narrow 6-point margin, 25 percent to 19 percent, says Palin’s selection makes them more likely to support McCain, less than the 12-point positive impact of Biden on the Democratic ticket (22 percent more likely to support Barack Obama, 10 percent less so). -

Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls: a Question of Access

690 American Archivist / Vol. 56 / Fall 1993 Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/56/4/690/2748590/aarc_56_4_w213201818211541.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls: A Question of Access SARA S. HODSON Abstract: The announcement by the Huntington Library in September 1991 of its decision to open for unrestricted research its photographs of the Dead Sea Scrolls touched off a battle of wills between the library and the official team of scrolls editors, as well as a blitz of media publicity. The action was based on a commitment to the principle of intellectual freedom, but it must also be considered in light of the ethics of donor agreements and of access restrictions. The author relates the story of the events leading to the Huntington's move and its aftermath, and she analyzes the issues involved. About the author: Sara S. Hodson is curator of literary manuscripts at the Huntington Library. Her articles have appeared in Rare Books & Manuscripts Librarianship, Dictionary of Literary Biography Yearbook, and the Huntington Library Quarterly. This article is revised from a paper delivered before the Manuscripts Repositories Section meeting of the 1992 Society of American Archivists conference in Montreal. The author wishes to thank William A. Moffett for his encour- agement and his thoughtful and invaluable review of this article in its several revisions. Freeing the Dead Sea Scrolls 691 ON 22 SEPTEMBER 1991, THE HUNTINGTON scrolls for historical scholarship lies in their LIBRARY set off a media bomb of cata- status as sources contemporary with the time clysmic proportions when it announced that they illuminate. -

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary.