European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (Cepej)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Finance Benchmarking Toolkit: Piloting and Lessons Learned

fdaşlığ тво East нерс рт Strengthening Institutional Frameworks ідне па tenariat Orientalteneriatul Esti for Local Governance 2015-2017 Par ar ğı P artnership P Pa fdaşlıq во Eastern r T eneriatul Estic Східне пар Local Finance tnership enariat Oriedaşl art r f q t ten fda ar r Par r Benchmarking ıq тво Easter rq t fdaşlıq P fdaşlıq r нерс во Eastern P r T рт т T нерс рт Toolkit: Східне хідне па eneriatul Estic Ş па a art eneriatultnership Estic Ş P teneriatul Estic Східне ar at Oriental Східне паOrientala r P artnership P daşlığı P enariat O artnership tenariat Ofd piloting and stern f art P ar r r q t во Eastern P r q t ст Eastern daşlıq P r fdaşlığı P во Ea r f r т T lessons learned q t тво Ea r нерс Estic iatul Estichip Ş Схід eneriatu t artnership atul Estic Ş нерс l Estic Ş eriatul Estic Par tener daşlığ Східне парт ar r f rtnership P tenariat Oriental тво Eastern P rq t ip ar с eneri ер во Східне парт t не т MOLDOVA ar daşlığı P нерс P r f eneriatul Estic Ş tners Східне парт art tenariat Oriental ar P en P LOCAL FINANCE BENCHMARKING TOOLKIT: PILOTING AND LESSONS LEARNED Східне парт t Par tnership Par Par ENG tnership tenariat Oriental n tn ar ar rtenariat OrientalP ar Eastern f P Pa во r l q Eastern ğ ern The Council of Europe is the continent’s leading human rights The European Union is a unique economic and political partnership http://eap-pcf-eu.coe.int organisation. -

WCC Moldova Partnership Program Report on Activities for 2003-2004

WCC Moldova Partnership Program Report on activities for 2003-2004 Chisinau, 2005 Content I. BACKGROUND INFORMATION .................................................................................................. 3 1. SOCIO-ECONOMIC SITUATION ........................................................................................................... 3 2. POPULATION ................................................................................................................................ 4 3. CHURCHES REPRESENTED ........................................................................................................ 4 II. MOLDOVA PARTNERSHIP PROGRAMME ............................................................................. 7 1. BRIEF HISTORY OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................... 7 2. MOLDOVAN PARTNERSHIP PROGRAM INITIATIVES 2003-2004. ..................................... 10 III. SUMMARY OF PROJECT REPORTS ..................................................................................... 17 1. SOCIAL PROTECTION HUB ...................................................................................................... 17 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ............................................................................................................. 17 PARTNERS’ INITIATIVES IMPLEMENTED: ............................................................................................. 18 MO/002 -Soup Kitchen for elderly people ................................................................................... -

Dynamics and Branch Structure of Water Consumptions in the Republic of Moldova

DOI 10.1515/pesd-2017-0036 PESD, VOL. 11, no. 2, 2017 DYNAMICS AND BRANCH STRUCTURE OF WATER CONSUMPTIONS IN THE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA Bacal Petru, Burduja Daniela1 Keywords: river basins, water use, agriculture, household Abstract. The purpose of this research consists in the elucidation of spatial and branch aspects of the water use in the river basins of Republic of Moldova.The main topics presented in this paper are: 1)the dynamics of water use; 2)spatial and branch profile of water use and its dynamics: 3) existing problems in the evaluation and monitoring of water use. To achieve these objectives were used traditional methods of geographical and economic research. Also, the content of the present study is focused on the methodology to elaborate the management plans of hydrographical basins and their chapters on economic analysis of water use in the river basin. of Republic of Moldova. INTRODUCTION The hydrographical network of the Republic of Moldova comprises 2 hydrographic districts (HD): Dniester and Prut-Danube-Black Sea (PDBS), which includes 4 drainage basins, including the rivers Dniester, Prut, Danube rivers and rivers, which are flowing directly into the Black Sea. The last two drainage basins form the Danube-Black Sea Hydrographical Space (DBS HS), which together with the Prut river basin form the second hydrographic district – PDBS (figure 1). Within the boundaries of the Republic of Moldova, the Dniester river basin occupies an area of 19.2 thousand km²,which is more than ¼ (26.5%) of the total area,over 72 thousand km², -

Coe/EU Eastern Partnership Programmatic

CoE/EU Eastern Partnership Programmatic Co-operation Framework (PCF) 2015-2017 Project on “Strengthening the efficiency, professionalism and accountability of the judiciary in the Republic of Moldova” Launching of the court coaching programme on implementation of CEPEJ tools in the pilot courts of the Republic of Moldova LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Date: 04 September 2015, 10:00 – 17:00 Venue: Complexul turistic “Vatra”, or. Vadul-lui-Vodă, Parcul Nistrean Name, Surname, Title 1. Mr Jose-Luis Herrero, Head of Council of Europe in Chisinau 2. Mr Leonid Antohi, Project Coordinator, Council of Europe 3. Mr Ivan Crnčec, CEPEJ member (Croatia) 4. Mr Frans Van Der Doelen, CEPEJ member (The Netherlands) 5. Mr Fotis Karayannopoulos, Lawyer, CEPEJ expert (Greece) 6. Mr Jaša Vrabec, National Correspondent to the CEPEJ (Slovenia) 7. Mr Ruslan Grebencea, Senior Project Officer, Council of Europe in Chisinau 8. Mr Dumitru Visterniceanu, Superior Council of Magistracy 9. Mrs Palanciuc Victoria, Administration of courts Division, Ministry of Justice 10. Mrs Vitu Natalia, Head of judicial statistics service within the Department of Justice Administration, Ministry of Justice 11. Ms Lilia Grimalschi, Head of Department of analysis and enforcement of ECtHR Judgments, Ministry of Justice 12. Mr Oleg Melniciuc, President of Riscani District Court 13. Mrs Zinaida Dumitrasco, Head of the Secretariat, Riscani District Court, mun. Chisinau 14. Mrs Mocan Natalia, Head of generalization and systematization of judicial practice Service, Riscani District Court 15. Ms Eugenia Parfeni, Head of Department for systematization, generalization of judicial practice and PR, Riscani District Court 16. Mr Dvurecenschii Evghenii, judge, Cahul Court of Appeal 17. Mrs Hantea Svetlana, Head of Secretariat, Cahul Court of Appeal 18. -

Local Integration Project for Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine

LOCAL INTEGRATION PROJECT FOR BELARUS, MOLDOVA AND UKRAINE 2011-2013 Implemented by the United Nations High Funded by the European Union Commissioner for Refugees 12 June 2012 Refugees to receive apartments under EU/UNHCR scheme CHISINAU, Moldova, June 12 (UNHCR) – Four apartments rehabilitated to shelter refugees fleeing human rights abuse and conflict in their home countries have been given today to local authorities in Razeni, Ialoveni District by the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) following extensive rehabilitation works co-funded by the EU/UNHCR under the Local Integration Project (LIP) for refugees. Refugee families from Armenia, Azerbaijan and Palestine received ceremonial keys at today’s hand-over ceremony. Razeni Mayor Ion Cretu hosted Deputy Minister Ana Vasilachi (Ministry of Labour, Social Protection and the Family), Deputy Minister Iurie Cheptanaru (Ministry of Internal Affairs), Ambassador of the European Union Dirk Schübel and other dignitaries. Tuesday’s ceremony at the long-disused kindergarten follows a similar event in March when UNHCR formally handed over apartments at a former public bathhouse in Mereni, Anenii Noi District to shelter refugees from Armenia, Russia and Sudan. “Without the enthusiastic support of the mayors, council and residents of Mereni and Razeni villages, which offered the dilapidated buildings to UNHCR for renovation into apartments, this pilot refugee housing project would not have been possible,” said UNHCR Representative Peter Kessler. The refugees getting the new apartments were carefully selected based on their skills and willingness to contribute to their new host communities by a team including the Refugee Directorate of the Bureau for Migration and Asylum in the Ministry of Internal Affairs, UNHCR and its NGO implementing partners. -

Road Infrastructure Development of Moldova

Government of The Republic of Moldova Ministry of Economy and Infrastructure Road infrastructure development Chisinau 2017 1 … Road Infrastructure Road network Public roads 10537 km including: National roads 3670 km, including: Asphalt pavement 2973 km Concrete pavement 437 km Macadam 261 km Local roads 6867 km, Asphalt pavement 3064 km Concrete pavement 46 km Macadam 3756 km … 2 Legal framework in road sector • Transport and Logistic Strategy 2013 – 2022 approved by Government Decision nr. 827 from 28.10.2013; • National Strategy for road safety approved by Government Decision nr. 1214 from 27.12.2010; • Road Law nr. 509 from 22.06.1995; • Road fund Law nr. 720 from 02.02.1996 • Road safety Law nr. 131 from 07.06.2007 • Action Plan for implementing of National strategy for road safety approved by Government Decision nr. 972 from 21.12.2011 3 … Road Maintenance in the Republic of Moldova • The IFI’s support the rehabilitation of the road infrastructure EBRD, EIB – National Roads, WB-local roads. • The Government maintain the existing road assets. • The road maintenance is financed from the Road Fund. • The Road Fund is dedicated to maintain almost 3000km of national roads and over 6000 km of local roads • The road fund is part of the state budget . • The main strategic paper – Transport and Logistics Strategy 2013-2022. 4 … Road Infrastructure Road sector funding in 2000-2015, mil. MDL 1400 976 461 765 389 1200 1000 328 800 269 600 1140 1116 1025 1038 377 400 416 788 75 200 16 15 583 200 10 2 259 241 170 185 94 130 150 0 63 63 84 2000 -

Civil Protection and Emergency Situations Service Republic of Moldova Intervention Zone Chisinau

CIVIL PROTECTION AND EMERGENCY SITUATIONS SERVICE REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA INTERVENTION ZONE CHISINAU INTERVENTION Max 40 km from the ZONE base camp FIELD CAMP Costesti region, Ialoveni district 20 km South from Chişinău COSTESTI EXERCISE SITES AND PARTICULAR TACTICAL SITUATIONS Module I. IALOVENI Liquidation of the consequences at the damaged apartment building Tactical situation: • As a result of earthquake, a five level apartment building has been damaged in the Ialoveni area. • The stairs between floors are destroyed and concrete blocks of the roof and walls have fallen. Because of multiple damages to energy lines, a fire has stared in the building. Transport units which were around the building have been affected, the earthquake victims have been trapped in the block. Due of damages to the stairs, a large number of the people remain trapped on the upper floors, unable to escape. • Some rooms in the basement was flooded due to damages of the utility networks. • An unknown number of people remain under the rubble. • A fire has also broken out in the underground. • Near the building an traffic accident have occurred with a truck which transport the radioactive waste. As a consequences, around this area have dispersed several radioactive sources. LOCATION I. – IALOVENI, Apartament Building 10 km from camp Organizational Scheme: Module I. Ialoveni apartment building Intervention commander Tactical situations (OSC) Tactical situations International teams Workshop 15 Commanders of CP commanders Pumping water from and ES Service teams flooded rooms, Workshop 13 Workshop 14 International Teams CP and ES Service Maintaining public Affected people Teams order camp Workshop 9 Workshop 10 Workshop 11 Workshop 12 Territory Equipment Staff Mobile hospital decontamination decontamination decontamination Workshop 5 Workshop 6 Workshop 7 Workshop 8 Rescue Rescue from Underground Radiation research from the cars rubbles searching Workshop 1 Workshop 2 Workshop 3 Workshop 4 General search Fire Extinguishment Search with dogs Rescue from heights Module II. -

Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP)

Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP) Ialoveni City 2016-2030 CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 4 2. OVERALL STRATEGY ...................................................................................................... 11 2.1 OBJECTIVES AND TARGETS ............................................................................................ 11 2.2 CURRENT FRAMEWORK AND VISION FOR THE FUTURE .................................................. 14 2.2.1 BUILDINGS .................................................................................................................. 15 2.2.2 PUBLIC LIGHTING ........................................................................................................ 23 2.2.3 TRANSPORT ................................................................................................................ 25 2.2.4 ENERGY ...................................................................................................................... 28 2.2.5 WATER & WASTEWATER ............................................................................................. 35 2.2.6 WASTE........................................................................................................................ 38 3. ORGANISATIONAL AND FINANCIAL ASPECT ................................................................. 39 4. BASELINE EMISSION INVENTORY (BEI) ....................................................................... -

Medium Sized Project Proposal

0(',806,=('352-(&7352326$/ 5(48(67)25*())81',1* Public Disclosure Authorized FINANCING PLAN (US$) AGENCY’S PROJECT ID: 3 GEF PROJECT/COMPONENT GEFSEC PROJECT ID: COUNTRY: REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA Project 972,920 PROJECT TITLE: RENEWABLE ENERGY FROM PDF A* 25,000 AGRICULTURAL WASTES (REAW) SUB-TOTAL GEF 997,920 GEF AGENCY: WORLD BANK CO-FINANCING** OTHER EXECUTING AGENCY (IES): CONSOLIDATED IBRD/IDA/IFC AGRICULTURAL PROJECTS MANAGEMENT Government 1,434,950 Bilateral DURATION: 3 YEARS NGOs GEF FOCAL AREA: CLIMATE CHANGE Others 219,388 GEF OPERATIONAL PROGRAM: OP # 6 Sub-Total Co-financing: 1,654,338 Public Disclosure Authorized GEF STRATEGIC PRIORITY: CC 4 Total Project Financing: 2,652,258 ESTIMATED STARTING DATE: MAY 2005 FINANCING FOR ASSOCIATED ACTIVITY MPLEMENTING GENCY EE I A F : $146,000 IF ANY: N/A * PDFA approved on 23.03.2004 ** Details provided in the Financing Section CONTRIBUTION TO KEY INDICATORS OF THE BUSINESS PLAN: The project will contribute to the established target for OP#6 by removing barriers for the use of renewable energy from agricultural wastes in Moldova, and will reduce high implementation costs of such energy technologies due to low-volume of replication. Public Disclosure Authorized RECORD OF ENDORSEMENT ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT: Constantin Mihalescu, minister of Ministry of Environmental and Natural Date: 16 February 2005 Recourses of Moldova, GEF National Focal Point This proposal has been prepared in accordance with GEF policies and procedures and meets the standards of the GEF Project Review Criteria for a Medium-sized Project. Project Contact Person: Emilia Battaglini, ECA Regional Coordinator Tel. -

Regional Business Environment Development Index 2016

IDIS Viitorul INEKO Regional Business Environment Development Index 2016 Authors Liubomir Chiriac, PhD, Vice Director IDIS Viitorul Tatiana Lariusin, PhD, Senior Economist, IDIS Viitorul Ion Butmalai, Economist, IDIS Viitorul Peter Golias, PhD, Director, INEKO Official Development Assistance of the Slovak Republic is an intrinsic instrument of the Slovak foreign policy, which to a large extent shapes Slovakia’s relations with aid recipients and relevant international organizations. Having committed itself to the fulfillment of the Millennium Development Goals, Slovakia shares the responsibility for global development and poverty reduction endeavors in developing countries, aiming to promote their sustainable development. INEKO Institute is a non-governmental non-profit organization established in support of economic and social reforms which aim to remove barriers to the long-term positive development of the Slovak economy and society. Mission The Institute’s mission is to support a rational and efficient economic and social reform process in the Slovak Republic (SR), through research, information development and dissemination, advice to senior government, political and selfgoverning officials, and promotion of the public discourse. It also focuses on those areas of social policy on the regional as well as the European level critical to the economic transformation of the SR. It draws on the best experience available from other transition countries and members of the European Union (EU) and the OECD. Regional Business Environment Development Index 2016 Authors Liubomir Chiriac, PhD, Vice Director IDIS Viitorul Tatiana Lariusin, PhD, Senior Economist, IDIS Viitorul IDIS is an independent think tank, established in 1993 as a Ion Butmalai, Economist, IDIS Viitorul research and advocacy think tank, incorporated by Moldovan Peter Golias, PhD, Director, INEKO laws on non-for-profit and NGOs. -

The Regional Pecularities of Water Use in the Republic of Moldova

Lucrările Seminarului Geografic Dimitrie Cantemir Vol. 46, Issue 2, October 2018, pp. 19-37 http://dx.doi.org/10.15551/lsgdc.v46i2.02 Research article The Regional Pecularities of Water Use in the Republic of Moldova Petru Bacal 1 , Daniela Burduja 1 1 Institute of Ecology and Geography, Academy of Economic Science of Moldova Abstract. The purpose of this research consists in the elucidation of regional and branch aspects of the water use in the Republic of Moldova. The main topics presented in this paper are: 1) the regional delimitations of the Republic of Moldova; 2) resources of surface water and groundwater: 3) regional aspects of water use; 4) dynamics of water use by abstracted sources and by the main usage categories; 5) branch profile of water use and its dynamics: 6) existing problems in the evaluation and monitoring of water use. Keywords: water use, region, technological, agriculture, household. 1. Introduction According to the economic-geographic criterion, the Republic of Moldova (RM) is divided into 4 distinct regions: Northern, Central, Southern and Eastern (figure 1). The North Region (NR) overlaps with the North Development Region, established by the RM Law on Regional Development (Legea nr. 438/2006) and comprises 11 districts from the northern part of the Republic of Moldova, as well as the Balti municipality. The total area of North Region is 10 thousand km2, which represents more than 30% of the total area of the Republic (table 1). The population of this region is 987 thousand inhabitants (25%), including 150 thousand inhabitants - in the Balti city. The largest part of NR is located within the Raut river (the main right tributary of the Dniester River) basin, including the districts of Donduseni, Soroca, Drochia, Floresti, Singerei, as well as Balti municipality. -

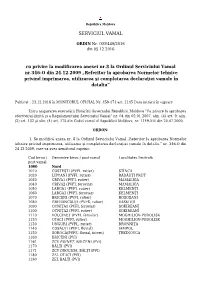

Serviciul Vamal

Republica Moldova SERVICIUL VAMAL ORDIN Nr. OSV449/2016 din 05.12.2016 cu privire la modificarea anexei nr.8 la Ordinul Serviciului Vamal nr.346-O din 24.12.2009 „Referitor la aprobarea Normelor tehnice privind imprimarea, utilizarea şi completarea declaraţiei vamale în detaliu” Publicat : 23.12.2016 în MONITORUL OFICIAL Nr. 459-471 art. 2145 Data intrării în vigoare Întru asigurarea executării Hotărîrii Guvernului Republicii Moldova ”Cu privire la aprobarea efectivului-limită și a Regulamentului Serviciului Vamal” nr. 04 din 02.01.2007, alin. (4) art. 9, alin. (2) art. 132 şi alin. (4) art. 175 din Codul vamal al Republicii Moldova, nr. 1149-XIV din 20.07.2000, ORDON: 1. Se modifică anexa nr. 8 la Ordinul Serviciului Vamal „Referitor la aprobarea Normelor tehnice privind imprimarea, utilizarea şi completarea declaraţiei vamale în detaliu.” nr. 346-O din 24.12.2009, care va avea următorul cuprins: Cod birou / Denumire birou / post vamal Localitatea limitrofă post vamal 1000 Nord 1010 COSTEȘTI (PVFI, rutier) STÎNCA 1020 LIPCANI (PVFI, rutier) RĂDĂUȚI PRUT 1030 CRIVA1 (PVFI, rutier) MAMALIGA 1040 CRIVA2 (PVFI, feroviar) MAMALIGA 1050 LARGA1 (PVFI, rutier) KELMENȚI 1060 LARGA2 (PVFI, feroviar) KELMENȚI 1070 BRICENI (PVFI, rutier) ROSOȘANI 1080 GRIMĂNCĂUȚI (PVFS, rutier) VASKIVȚI 1090 OCNIȚA1 (PVFI, feroviar) SOKIREANÎ 1100 OCNIȚA2 (PVFI, rutier) SOKIREANÎ 1110 VOLCINEȚ (PVFI, feroviar) MOGHILIOV-PODOLISK 1120 OTACI (PVFI, rutier) MOGHILIOV-PODOLISK 1130 UNGURI (PVFL, rutier) BRONNIȚA 1140 COSĂUȚI (PVFI, fluvial) IAMPOL 1150 SOROCA(PVFS,