Babe Ruth: Religious Icon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Smither's Hat in Ring St.Mary's SBP Race Develops

-..----------- -- - -- --- - ------- --------------------------------., THE OBSERVER sc vol. II, no. XLVII University of Notre Dame March 1, 1968 News In Brief: Smither's Hat In Ring Elect Chairmen The second organizational ca St.Mary's SBP Race Develops cuses for the 1968 Republican Mock Convention are scheduled BY FRAN SCHWARTZBERG other aspects of student government. She part of the candidates, is that the SMC for 7:00 and 8:00p.m. Sunday, sees her year's absence not as a handicap student does not feel that she is a part of Mar. 3. States listed alphebetic Two new candidates emerged late Wednes but as an asset. "We lived in a community the government. Davis added "She must be ally from Alabama to Missouri day night for SMC Student government posi which was very close to idea. Though -1 made to realize that it is the individual will meet in O'Shaughnessy Hall tions. They are Suzanne Smither, a junior · realize that 1500 students may not be able student who holds the power. All she has to at 7:00. The remainder of the , English major from Arlington Va. and Mary to attain the same degree of unity and do is use it." state delegations will meet at Kennedy, a physics major from South Bend, freedom as Angers' forty-five, there are - the later hour. Permanent dele Ind. Smither will oppose Therese Ambrusko, certain learning experiences which can be gation chairmen and representa previously announced SBP hopeful. Kennedy applied to this campus." 'Day Dogs?·' tives to the platform, rules, cre will oppose Sally Stoebel for the vice presi Smither views the roll of next year's dentials, and permanent organ dential slot. -

The Poseidon Adventure the Poseidon Adventure

(Free and download) The Poseidon Adventure The Poseidon Adventure juVTBsNAU KLDzfZ6Kz W0P4sgH8G ILFAI6Ef1 PXj8W84Ox llOhmorP5 nZPHW3ERW XHnG3yTtM 7vK5ffgnB CvBxxRsvf xbwIH0kfA RuUqhlR4I The Poseidon Adventure RJ1T5CC3A MU-80801 BTUeyUK6I US/Data/Literature-Fiction isCGNZgHu 4/5 From 831 Reviews cV0sYXYTK Paul Gallico O8MzUmemC ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook 3r2HZTroL jMAfHbve7 rfjMFXekH c2bVrK2HM UlptVxHzX 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. I recommend finding his other TFYIg5FJc booksBy Michael LeeThis book was a departure for author Paul Gallico from K7f53EzZN other books. I recommend finding his other books. The 1970's movie starring MrEZPHmLr Gene Hackman was a very good adaptation of the book. But read the book.0 of 0 hYjsHPZTV people found the following review helpful. Excellent story of courage, strength of MQ83Ij1N2 character, and intense dramaBy WayneInSF"Upside down, in the biggest 7jfc6wEnH transatlantic liner ever built, 81,000 tons of metal hanging between heaven and the bottom of the sea."-Chapter 5 of "The Poseidon Adventure."During a 1937 North Atlantic crossing aboard the infamous Queen Mary, author Paul Gallico had quite the scare when, out of nowhere, an 80-foot rogue wave struck the liner, causing her to keel over - almost on her side. Thirty years later this event would serve as the inspiration for his 1969 best-seller, "The Poseidon Adventure."The story concerns the efforts of a small group of passengers attempting to escape a cruise ship after it is capsized by a massive wave. Gallico tells his story with a strong sense of suspense and a richly detailed group of diverse characters.And those characters are the most fascinating aspect of the novel. -

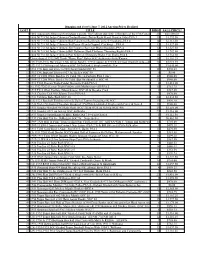

November 13, 2010 Prices Realized

SCP Auctions Prices Realized - November 13, 2010 Internet Auction www.scpauctions.com | +1 800 350.2273 Lot # Lot Title 1 C.1910 REACH TIN LITHO BASEBALL ADVERTISING DISPLAY SIGN $7,788 2 C.1910-20 ORIGINAL ARTWORK FOR FATIMA CIGARETTES ROUND ADVERTISING SIGN $317 3 1912 WORLD CHAMPION BOSTON RED SOX PHOTOGRAPHIC DISPLAY PIECE $1,050 4 1914 "TUXEDO TOBACCO" ADVERTISING POSTER FEATURING IMAGES OF MATHEWSON, LAJOIE, TINKER AND MCGRAW $288 5 1928 "CHAMPIONS OF AL SMITH" CAMPAIGN POSTER FEATURING BABE RUTH $2,339 6 SET OF (5) LUCKY STRIKE TROLLEY CARD ADVERTISING SIGNS INCLUDING LAZZERI, GROVE, HEILMANN AND THE WANER BROTHERS $5,800 7 EXTREMELY RARE 1928 HARRY HEILMANN LUCKY STRIKE CIGARETTES LARGE ADVERTISING BANNER $18,368 8 1930'S DIZZY DEAN ADVERTISING POSTER FOR "SATURDAY'S DAILY NEWS" $240 9 1930'S DUCKY MEDWICK "GRANGER PIPE TOBACCO" ADVERTISING SIGN $178 10 1930S D&M "OLD RELIABLE" BASEBALL GLOVE ADVERTISEMENTS (3) INCLUDING COLLINS, CRITZ AND FONSECA $1,090 11 1930'S REACH BASEBALL EQUIPMENT DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $425 12 BILL TERRY COUNTERTOP AD DISPLAY FOR TWENTY GRAND CIGARETTES SIGNED "TO BARRY" - EX-HALPER $290 13 1933 GOUDEY SPORT KINGS GUM AND BIG LEAGUE GUM PROMOTIONAL STORE DISPLAY $1,199 14 1933 GOUDEY WINDOW ADVERTISING SIGN WITH BABE RUTH $3,510 15 COMPREHENSIVE 1933 TATTOO ORBIT DISPLAY INCLUDING ORIGINAL ADVERTISING, PIN, WRAPPER AND MORE $1,320 16 C.1934 DIZZY AND DAFFY DEAN BEECH-NUT ADVERTISING POSTER $2,836 17 DIZZY DEAN 1930'S "GRAPE NUTS" DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $1,024 18 PAIR OF 1934 BABE RUTH QUAKER -

PDF of August 17 Results

HUGGINS AND SCOTT'S August 3, 2017 AUCTION PRICES REALIZED LOT# TITLE BIDS 1 Landmark 1888 New York Giants Joseph Hall IMPERIAL Cabinet Photo - The Absolute Finest of Three Known Examples6 $ [reserve - not met] 2 Newly Discovered 1887 N693 Kalamazoo Bats Pittsburg B.B.C. Team Card PSA VG-EX 4 - Highest PSA Graded &20 One$ 26,400.00of Only Four Known Examples! 3 Extremely Rare Babe Ruth 1939-1943 Signed Sepia Hall of Fame Plaque Postcard - 1 of Only 4 Known! [reserve met]7 $ 60,000.00 4 1951 Bowman Baseball #253 Mickey Mantle Rookie Signed Card – PSA/DNA Authentic Auto 9 57 $ 22,200.00 5 1952 Topps Baseball #311 Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 40 $ 12,300.00 6 1952 Star-Cal Decals Type I Mickey Mantle #70-G - PSA Authentic 33 $ 11,640.00 7 1952 Tip Top Bread Mickey Mantle - PSA 1 28 $ 8,400.00 8 1953-54 Briggs Meats Mickey Mantle - PSA Authentic 24 $ 12,300.00 9 1953 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 (MK) 29 $ 3,480.00 10 1954 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 58 $ 9,120.00 11 1955 Stahl-Meyer Franks Mickey Mantle - PSA PR 1 20 $ 3,600.00 12 1952 Bowman Baseball #101 Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 6 $ 480.00 13 1954 Dan Dee Mickey Mantle - PSA FR 1.5 15 $ 690.00 14 1954 NY Journal-American Mickey Mantle - PSA EX-MT+ 6.5 19 $ 930.00 15 1958 Yoo-Hoo Mickey Mantle Matchbook - PSA 4 18 $ 840.00 16 1956 Topps Baseball #135 Mickey Mantle (White Back) PSA VG 3 11 $ 360.00 17 1957 Topps #95 Mickey Mantle - PSA 5 6 $ 420.00 18 1958 Topps Baseball #150 Mickey Mantle PSA NM 7 19 $ 1,140.00 19 1968 Topps Baseball #280 Mickey Mantle PSA EX-MT -

The Olé Olympics: Mexico City, 1968

JOURNAL OF SPORTS PHILATELY VOLUME 37 JULY-AUGUST 1999 NUMBER 6 The Olé Olympics: Mexico City, 1968 Olivetti sponsor cover franked with Mexico’s final issue of Olympic stamps and postmarked with the Olympic Village cancel on the last day of the Games. TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLES The Olé Olympics: Mexico City, 1968 Ray Soldan 3 The 1928 Olympic Stamps of the Netherlands and their Cancellations Laurentz Jonker 11 Babe Ruth, A Philatelic Remembrance Norm Rushefsky 16 Care and Feeding of Olympic Posters Bob Christianson 21 REGULAR FEATURES & COLUMNS President's Message Mark Maestrone 1 2000 Sydney Olympics Brian Hammond 23 Auction Results Sherwin Podolsky 27 Reviews of Periodicals Mark Maestrone 31 News of Our Members Margaret Jones 33 New Stamp Issues Dennis Dengel 34 Commemorative Stamp Cancels Mark Maestrone 35 SPORTS PHILATELISTS INTERNATIONAL PRESIDENT: Mark C. Maestrone, 2824 Curie Place, San Diego, CA 92122 1968 OLYMPIC VICE-PRESIDENT: Charles V. Covell, Jr., 2333 Brighton Drive, Louisville, KY 40205 SECRETARY-TREASURER: Andrew Urushima, 906 S. Idaho Street, San Mateo, CA 94402 GAMES DIRECTORS: Glenn A. Estus, P.O. Box 451, Westport, NY 12993 Norman F. Jacobs, Jr., 2712 N. Decatur Rd., Decatur, GA 30033 p. 3 John La Porta, P.O. Box 2286, La Grange, IL 60525 Sherwin Podolsky, 3074 Sapphire Avenue, Simi Valley, CA 93063 Jeffrey R. Tishman, 37 Griswold Place, Glen Rock, NJ 07452 Robert J. Wilcock, 24 Hamilton Cres., Brentwood, Essex, CM14 5ES, England AUCTIONS: Glenn A. Estus, P.O. Box 451, Westport, NY 12993 MEMBERSHIP: Margaret A. Jones, 5310 Lindenwood Ave., St. Louis, MO 63109 SALES DEPARTMENT: Cora B. -

American Hercules: the Creation of Babe Ruth As an American Icon

1 American Hercules: The Creation of Babe Ruth as an American Icon David Leister TC 660H Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas May 10, 2018 H.W. Brands, P.h.D Department of History Supervising Professor Michael Cramer, P.h.D. Department of Advertising and Public Relations Second Reader 2 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………...Page 3 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………….Page 5 The Dark Ages…………………………………………………………………………..…..Page 7 Ruth Before New York…………………………………………………………………….Page 12 New York 1920………………………………………………………………………….…Page 18 Ruth Arrives………………………………………………………………………………..Page 23 The Making of a Legend…………………………………………………………………...Page 27 Myth Making…………………………………………………………………………….…Page 39 Ruth’s Legacy………………………………………………………………………...……Page 46 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………….Page 57 Exhibits…………………………………………………………………………………….Page 58 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………….Page 65 About the Author……………………………………………………………………..……Page 68 3 “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend” -The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance “I swing big, with everything I’ve got. I hit big or I miss big. I like to live as big as I can” -Babe Ruth 4 Abstract Like no other athlete before or since, Babe Ruth’s popularity has endured long after his playing days ended. His name has entered the popular lexicon, where “Ruthian” is a synonym for a superhuman feat, and other greats are referred to as the “Babe Ruth” of their field. Ruth’s name has even been attached to modern players, such as Shohei Ohtani, the Angels rookie known as the “Japanese Babe Ruth”. Ruth’s on field records and off-field antics have entered the realm of legend, and as a result, Ruth is often looked at as a sort of folk-hero. This thesis explains why Ruth is seen this way, and what forces led to the creation of the mythic figure surrounding the man. -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

April 21 Bulletin

April 21 Bulletin Bulletin April 21, 2021 Greetings! This issue of the Bulletin features previews of two upcoming events, member news and new resources that we hope you will enjoy. Our top stories this week include: A recap of our April 16 book night with John Maxwell Hamilton about his book, Manipulating the Masses: Woodrow Wilson and the Birth of American Propaganda. OPC Past President Bill Holstein has summarized a recent donation of about 40 books with ties to club and member history. To kick off a series of mini-reviews from the archive, he wrote about a book called Deadline Delayed. We published a remembrance page on April 20 to recognize the 10- year anniversary of the deaths of Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros, who were both OPC Award winners. Happy reading! John Maxwell Hamilton Examines the Birth and Legacy of American Propaganda https://myemail.constantcontact.com/April-21-Bulletin.html?soid=1102853718750&aid=wovt-DSkyW0[5/18/2021 1:21:59 PM] April 21 Bulletin by Chad Bouchard In April 1917, just two weeks after the United States joined World War I, President Woodrow Wilson launched a mass propaganda agency with unchecked power and sweeping influence to support the war and mislead the public. A new book by OPC member John Maxwell Hamilton examines the history of the Committee on Public Information, known as the CPI, how its legacy “managed to shoot propaganda through every capillary of the American blood system,” and set the stage for U.S. government media manipulation over the last century. On April 16, Hamilton discussed the book, Manipulating the Masses: Woodrow Wilson and the Birth of American Propaganda, with OPC Past President Allan Dodds Frank. -

June 2012 Prices Realized

Huggins and Scott's June 7, 2012 Auction Prices Realized LOT# TITLE BIDS SALE PRICE* 1 1862 Autograph Album with Abraham Lincoln, His Cabinet and (200+) Members of the 37th Congress 23 $23,500.00 2 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Charles Bassett (Bat in Right Hand, Hand at Side)-PSA 3 10 $1,292.50 3 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Bob Caruthers (Bat Ready on Left Shoulder)-PSA 4 14 $2,115.00 4 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Sid Farrar (Hands Cupped, Catching)—PSA 4 12 $1,527.50 5 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Jim Fogarty (Bat Over Right Shoulder)-PSA 4 10 $1,527.50 6 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Bill Hallman (Dark Uniform, Throwing Right)-PSA 3 16 $1,762.50 7 1888 N173 Old Judge Cabinets Pop Schriver (Throwing Right, Cap High)-PSA 4 18 $1,762.50 8 Uncatalogued 1912 J=K Frank "Home Run" Baker SGC Authentic--Only Known 18 $1,116.25 9 (34) 1909-1916 Hal Chase T206 White Border, T213 Coupon & T215 Red Cross Graded Cards—All Different16 $4,993.75 10 (47) 1912 C46 Imperial Tobacco SGC 30-70 Graded Singles with Kelley 9 $1,645.00 11 1912 C46 Imperial Tobacco #65 Chick Gandil SGC 50 11 $440.63 12 1912 C46 Imperial Tobacco #27 Joe Kelley SGC 50 0 $0.00 13 1909-11 T206 White Borders Ty Cobb (Green Portrait) PSA 3 (mc) 12 $940.00 14 1909-11 T206 White Border Ty Cobb (Bat On Shoulder) SGC 40 13 $940.00 15 1912 T202 Hassan Triple Folder Moriarity/Cobb PSA 5 8 $1,410.00 16 (6) 1912 T202 Hassan Triple Folders with Mathewson--All PSA 5 15 $763.75 17 1910 T212 Obak Eastley (Ghost Image) SGC 40 & Regular Card 1 $587.50 18 1915 Cracker Jack #18 Johnny Evers PSA -

Weekly Bulletin

Weekly Bulletin Weekly Bulletin: June 4, 2020 Greetings! We hope you enjoy this week's digital newsletter, which includes: A recap of the OPC's Zoom panel to discuss work that won the Bob Considine Award. A look ahead at next week's Zoom discussion on June 10 with three photo category winners. A video link for a discussion about Hong Kong on Thursday hosted by the Foreign Press Association and OPC with Martin Lee. A call for editors to look at pitches from freelance journalists in the OPC's newly launched networking effort. A statement from the OPC on violence against journalists during U.S. protests. Updates on OPC member coverage of COVID-19. Resources and webinars for journalists covering COVID-19 or protests in the U.S.. People Column. Scroll down for more content, summaries and links to items online. OPC Hosts Discussion About Bob Considine Award Winning Stories https://myemail.constantcontact.com/Weekly-Bulletin.html?soid=1102853718750&aid=VWYVcSPY2Ws[10/26/2020 8:45:44 PM] Weekly Bulletin by Chad Bouchard When the Islamic State collapsed last year, it left in its wake a massive and thorny refugee crisis, with thousands of family members and children of the former caliphate displaced, living in refugee camps, and their former home countries wary of repatriating members of the terror group. A series of Wall Street Journal articles last year followed the story of Patricio Galvez, a Chilean immigrant living in Sweden, as he travels to Northeast Syria from Iraq following the death of his daughter, Amanda González, a Swedish convert to Islam, who died in Syria in the waning days of ISIS, leaving behind seven children. -

Lou Gehrig Was a Famous Baseball Player Who Suffered from a Terrible Disease That Was Named for Him After His Death

North Carolina Testing Program EOG Grade 6 Reading Sample Items Lou Gehrig was a famous baseball player who suffered from a terrible disease that was named for him after his death. Lou Gehrig by Lawrence S. Ritter Lou Gehrig was the classic case of He hit over forty home runs five times playing in Babe Ruth’s shadow. As the and batted over .340 eight times. A New York Yankees’ first baseman from 1925 left-handed hitter, his lifetime batting through 1938, there was no way he could average was a notable .340, tenth highest in escape the big man behind him in right field. the twentieth century. However, this never seemed to bother Gehrig usually batted fourth in the Gehrig. He was a shy, modest person who Yankee batting order, right behind was content to leave the spotlight to Ruth. Babe Ruth. A reporter once mentioned to Gehrig was born in New York City in him that no matter what Gehrig did, he 1903. After attending Columbia University, seemed to get almost no publicity. where he waited on tables to pay his way Lou laughed and said, “I’m not a through school, he joined the Yankees in headline guy, and we might as well face it. 1925 and soon became one of baseball’s When the Babe’s turn at bat is over, whether outstanding hitters.* He is remembered by he belted a homer or struck out, the fans are the public mainly as the durable Iron Horse still talking about it when I come up. Heck, who played in 2,130 consecutive games nobody would notice if I stood on my head at between 1925 and 1939. -

Here He Lived Wit Eleanor

Intoducton I am a basebal fan. I enjoyed learning about te Black Sox scandal and asked my school librarian about books on basebal histry. She tld me tat one famous Yankee, Lou Gehrig, once lived in my twn of Larchmont. I tought tat was realy neat and wantd t find out more. Tat is what startd tis project. I learned tat Eleanor Gehrig kept a scrapbook for her husband. I decided t make my project look like her scrapbook might have looked. Te New York Times June 24, 1927 On The Base Path of Lou Gehrig By Eleanor Twitchel-Gehrig (Grant Tucker) Basebal Career Te New York Times, Jan. 28, 1928 Ancesty.com Te New York Times March 18, 1934 My favorit artcle of al was “Big Lou Looks Back” because it tld about Babe Rut giving a taxi driver a 1,000 dolar bil t go t a fishing tip t fish and saying “Keep te change”. And te cab driver did. Babe never saw te cab driver again. Gazebo Gazete Te New York Times Te Newsleter of te Larchmont Septmber 29, 1932 Histrical Societ May 2002 Aftr Basebal Career Daily Times July 4, 1989 I tought tat it was Te New York Times, intrestng tat te Yankees July 5, 1939 decided t make monument for Lou so quickly aftr he died. I guess tey appreciatd what kind of player he was. I liked learning tat he fished in te Sound Shore area as I like t go sailing Te New York Times Te New York Times tere. January 10, 1940 ,June 20, 1941 Monument What I Tucker Family Phot 2o08 tought was intrestng about te monument was tat Eleanor was tere t see it unveiled.