Implacable Images: Why Epileptiform Events Continue to Be Featured in film and Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case 2:18-Mj-00152-EFB Document 6 Filed 08/15/18 Page 1 of 32

Case 2:18-mj-00152-EFB Document 6 Filed 08/15/18 Page 1 of 32 1 MCGREGOR W. SCOTT United States Attorney 2 AUDREY B. HEMESATH HEIKO P. COPPOLA 3 Assistant United States Attorneys 501 I Street, Suite 10-100 4 Sacramento, CA 95814 Telephone: (916) 554-2700 5 CHRISTOPHER J. SMITH 6 Acting Associate Director 7 JOHN D. RIESENBERG Trial Attorney 8 Office of International Affairs Criminal Division 9 U.S. Department of Justice 1301 New York Avenue NW 10 Washington, D.C. 20530 11 Telephone: (202) 514-0000 12 Attorneys for Plaintiff 13 United States of America 14 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 15 EASTERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 16 17 IN THE MATTER OF 18 THE EXTRADITION OF OMAR AMEEN CASE NO. 2:18-MJ-0152 EFB 19 20 21 22 MEMORANDUM OF EXTRADITION LAW AND REQUEST 23 FOR DETENTION PENDING EXTRADITION PROCEEDINGS 24 25 26 27 28 Case 2:18-mj-00152-EFB Document 6 Filed 08/15/18 Page 2 of 32 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 2 I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND ..........................................................................................................1 3 II. LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF EXTRADITION PROCEEDINGS ...................................................2 4 A. The limited role of the Court in extradition proceedings. ....................................................2 5 B. The Requirements for Certification .....................................................................................3 6 1. Authority Over the Proceedings ...........................................................................3 7 2. Jurisdiction Over the Fugitive ..............................................................................4 -

Lost Prince Pack Latest

Miranda Richardson Miranda Richardson Miranda Richardson portrays Queen Mary, the Stranger,The Crying Game, Enchanted April, Damage, emotionally repressed mother of Prince John.A Empire Of The Sun,The Apostle and Spider (Official fundamentally inhibited character, she is a loving Selection, Cannes 2002), as well as the mother but has great difficulty communicating with unforgettable Queenie in the BBC’s Blackadder. She her son. says:“Mary had an absolute belief in the idea of duty. She thought that her husband’s word was the The actress, one of Britain’s most gifted screen law and believed in the divine right of kings. performers, immersed herself in research for the Although that view seems old-fashioned to us now, role and emerged with a clearer, more sympathetic she thought it could not be questioned. Ultimately, I idea about this often-maligned monarch. think this film understands Mary. It portrays her most sympathetically.” ‘’When people hear I’m playing Mary, they say, ‘Wasn’t she a dragon?’ But I’ve learnt from my For all that, Mary’s rigid adherence to the research that she wasn’t just a crabby old bag. She Edwardian code of ethics created a barrier may never have laughed in public, but that was between her and her independent-minded son, because she was shy. She felt she wasn’t able to Johnnie.“She loved him as fully as she could,” express her emotions in public.” Richardson reflects.“She knew that he was a free spirit who was able to be himself. Mary could never Miranda has gained a towering reputation for a be herself because she was always so serious, number of films, including Tom And Viv, Dance With A dedicated, dutiful and aware of her destiny. -

The American Postdramatic Television Series: the Art of Poetry and the Composition of Chaos (How to Understand the Script of the Best American Television Series)”

RLCS, Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72 – Pages 500 to 520 Funded Research | DOI: 10.4185/RLCS, 72-2017-1176| ISSN 1138-5820 | Year 2017 How to cite this article in bibliographies / References MA Orosa, M López-Golán , C Márquez-Domínguez, YT Ramos-Gil (2017): “The American postdramatic television series: the art of poetry and the composition of chaos (How to understand the script of the best American television series)”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 72, pp. 500 to 520. http://www.revistalatinacs.org/072paper/1176/26en.html DOI: 10.4185/RLCS-2017-1176 The American postdramatic television series: the art of poetry and the composition of chaos How to understand the script of the best American television series Miguel Ángel Orosa [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – [email protected] Mónica López Golán [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – moLó[email protected] Carmelo Márquez-Domínguez [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – camarquez @pucesi.edu.ec Yalitza Therly Ramos Gil [CV] [ ORCID] [ GS] Professor at the School of Social Communication. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (Sede Ibarra, Ecuador) – [email protected] Abstract Introduction: The magnitude of the (post)dramatic changes that have been taking place in American audiovisual fiction only happen every several hundred years. The goal of this research work is to highlight the features of the change occurring within the organisational (post)dramatic realm of American serial television. -

Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8g15z7t No online items Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002 Finding aid prepared by Performing Arts Special Collections Staff; additions processed by Peggy Alexander; machine readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Roy Huggins Papers, 1948-2002 PASC 353 1 Title: Roy Huggins papers Collection number: PASC 353 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Physical Description: 20 linear ft.(58 boxes) Date: 1948-2002 Abstract: Papers belonging to the novelist, blacklisted film and television writer, producer and production manager, Roy Huggins. The collection is in the midst of being processed. The finding aid will be updated periodically. Creator: Huggins, Roy 1914-2002 Restrictions on Access Open for research. STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact UCLA Library Special Collections for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UC Regents. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where The UC Regents do not hold the copyright. -

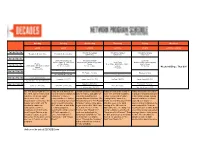

Visit Us on the Web at DECADES.Com

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Weekend 6/8/15 6/9/15 6/10/15 6/11/15 6/12/15 6/13/15 - 6/14/15 7a / 1p / 7p / 1a Through the Decades Through the Decades Through the Decades Through the Decades {CC} Through the Decades {CC} 150610 {CC} 150611 {CC} 150612 {CC} 8a / 2p / 8p / 2a Drifter: Henry Lee Lucas The Boston Strangler Love Field Antonio Sabato Jr., John Burke David Faustino, Andrew Divoff (2008) - Hanky Panky Michelle Pfeiffer, Dennis Haysbert Frances 9a / 3p / 9p / 3a (2009) - Thriller Thriller Gene Wilder, Gilda Radner (1982) - (1992) - Drama Jessica Lange, Kim Stanley (1982) - TV-14 L, S, V {CC} TV-14 L, V {CC} Comedy TV-14 {CC} Weekend Binge: That Girl Drama TV-PG {CC} TV-14 S, V {CC} Greatest Sports Legends: Secretariat 06 10a / 4p / 10p / 4a {CC} The Fugitive 153 {CC} Bonanza 527 {CC} Love, American Style 666 {CC} Disasters of the Century: Le Mans Race Car Crash 010 {CC} 11a / 5p / 11p / 5a I Love Lucy 155 {CC} Gunsmoke 7215 {CC} Hawaii Five-O 6817 {CC} The Saint 110 {CC} Daniel Boone 3007 {CC} Car 54, Where Are You? 051 {CC} 12p / 6p / 12a / 6a Naked City 0010 {CC} The Greats: Anne Frank 09 {CC} Gunsmoke 7413 {CC} Hawaii Five-O 7214 {CC} Route 66 13 {CC} The Achievers: Babe Ruth 12 {CC} Have Gun, Will Travel 118 {CC} Our look back begins on June Today we look back at the Serials kilers have an infamous Today we look at the events of Today we examine the topics 8th, 1949, with the Hollywood end of a historic manhunt for place in history, and today we June 11th. -

Adrian Edmondson Actor

Adrian Edmondson Actor Showreel Agents Lindy King Associate Agent Joel Keating [email protected] 0203 214 0871 Assistant Tessa Schiller [email protected] Lucia Pallaris Assistant [email protected] Eleanor Kirby +44 (0) 20 3214 0909 [email protected] Roles Television Production Character Director Company OUT OF HER MIND Lewis Ben Blaine & BBC Chris Blaine SAVE ME TOO Gideon Charles Kim Loach/Coky Sky Giedroyc EASTENDERS Daniel Cook Various BBC SUMMER OF ROCKETS Max Dennis Stephen Poliakoff BBC BANCROFT (Series 1 & Superintendent Cliff John Hayes ITV 2) Walker CHEAT William Louise Hooper Two Brothers Pictures RETRIBUTION Peter Elliot William McGregor BBC Scotland United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company STRIKE BACK James McKitterick Bill Eagles Sky One URBAN MYTHS Leslie Conn Jim O'Hanlon Sky Arts UPSTART CROW Sergeant Dogberry Richard Boden BBC SAVE ME Gideon Charles Various Gone Productions Ltd GENIUS David Hilbert Various EUE/Sokolow/National Geographic Channel ONE OF US Peter Elliott William McGregor BBC WAR AND PEACE Count Ilya Rostov Tom Harper BBC MISS AUSTEN REGRETS Henry Austen Jeremy Lovering BBC CHERNOBYL Legasov Nick Murphy BBC PREY DCI Warner Nick Murphy Red Production Company THE BLEAK OLD SHOP Headmaster Ben Gosling Fuller BBC OF STUFF Wackville RONJA, THE ROBBER'S Noodle Pete NHK Enterprises DAUGHTER HOLBY CITY Percy 'Abra' Durrant Various BBC JONATHAN -

Lost Prince,The

THE LOST PRINCE Francis Hodgson Burnett CONTENTS I The New Lodgers at No. 7 Philibert Place II A Young Citizen of the World III The Legend of the Lost Prince IV The Rat V ``Silence Is Still the Order'' VI The Drill and the Secret Party VII ``The Lamp Is Lighted!'' VIII An Exciting Game IX ``It Is Not a Game'' X The Rat-and Samavia XI Come with Me XII Only Two Boys XIII Loristan Attends a Drill of the Squad XIV Marco Does Not Answer XV A Sound in a Dream XVI The Rat to the Rescue XVII ``It Is a Very Bad Sign'' XVIII ``Cities and Faces'' XIX ``That Is One!'' XX Marco Goes to the Opera XXI ``Help!'' XXII A Night Vigil XXIII The Silver Horn XXIV ``How Shall We Find Him? XXV A Voice in the Night XXVI Across the Frontier XXVII ``It is the Lost Prince! It Is Ivor!'' XXVIII ``Extra! Extra! Extra!'' XXIX 'Twixt Night and Morning XXX The Game Is at an End XXXI ``The Son of Stefan Loristan'' THE LOST PRINCE I THE NEW LODGERS AT NO. 7 PHILIBERT PLACE There are many dreary and dingy rows of ugly houses in certain parts of London, but there certainly could not be any row more ugly or dingier than Philibert Place. There were stories that it had once been more attractive, but that had been so long ago that no one remembered the time. It stood back in its gloomy, narrow strips of uncared-for, smoky gardens, whose broken iron railings were supposed to protect it from the surging traffic of a road which was always roaring with the rattle of busses, cabs, drays, and vans, and the passing of people who were shabbily dressed and looked as if they were either going to hard work or coming from it, or hurrying to see if they could find some of it to do to keep themselves from going hungry. -

Susannah Buxton - Costume Designer

SUSANNAH BUXTON - COSTUME DESIGNER THE TIME OF THEIR LIVES Director: Roger Goldby. Producer: Sarah Sulick. Starring: Joan Collins and Pauline Collins. Bright Pictures. POLDARK (Series 2) Directors: Charles Palmer and Will Sinclair. Producer: Margaret Mitchell. Starring: Aiden Turner and Eleanor Tomlinson. Mammoth Screen. LA TRAVIATA AND THE WOMEN OF LONDON Director: Tim Kirby. Producer: Tim Kirby. Starring: Gabriela Istoc, Edgaras Montvidas and Stephen Gadd. Reef Television. GALAVANT Directors: Chris Koch, John Fortenberry and James Griffiths. Producers: Chris Koch and Helen Flint. Executive Producer: Dan Fogelman. Starring: Timothy Omundson, Joshua Sasse, Mallory Jansen, Karen David Hugh Bonneville, Ricky Gervais, Rutger Hauer and Vinnie Jones. ABC Studios. LORD LUCAN Director: Adrian Shergold. Producer: Chris Clough. Starring: Christopher Ecclestone, Michael Gambon, Anna Walton and Rory Kinnear. ITV. BURTON & TAYLOR Director: Richard Laxton. Producer: Lachlan MacKinnon. Starring: Helena Bonham-Carter and Dominic West. BBC. RTS CRAFT AND DESIGN AWARD 2013 – Best Costume Design. 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] DOWNTON ABBEY (Series I, Series II, Christmas Special) Directors: Brian Percival, Brian Kelly and Ben Bolt. Series Producer: Liz Trubridge. Executive Producer: Gareth Neame. Starring Hugh Bonneville, Jim Carter, Brendan Coyle, Michelle Dockery, Joanne Froggatt, Phyllis Logan, Maggie Smith and Elizabeth McGovern. Carnival Film & Television. EMMY Nomination 2012 – Outstanding Costumes for a Series. BAFTA Nomination 2012 – Best Costume Design. COSTUME DESIGNERS GUILD (USA) AWARD 2012 – Outstanding Made for TV Movie or MiniSeries. EMMY AWARD 2011 – Outstanding Costume Design. (Series 1). Emmy Award 2011 – Outstanding Mini-Series. Golden Globe Award 2012 – Best Mini Series or Motion Picture made for TV. -

RRFF-Gracenewsrelease2020 RRFF VERS 3

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE INTRODUCING GRACE’S ROCKIN’ ROLL ADVENTURE FEATURING ROCK AND ROLL HALL OF FAMER LITTLE STEVEN VAN ZANDT A NEW BOOK THAT USES MUSIC TO EMPOWER TEACHERS AND INSPIRE YOUNG STUDENTS IN READING, SCIENCE, AND MATH --Book and accompanying “STEAM” Lesson Plan Launched as Part of Rock and Roll Forever Foundation’s K-12 TeachRock Initiative --- New York, NY (October XX) – Grace’s Rockin’ Roll Adventure, a new children’s book featuring the characters from The Musical Adventures of Grace series accompanied by rock star and actor Steven Van Zandt, connects music and early elementary reading, science, and math. Developed as a partnership between TeachRock.org, the main initiative of Van Zandt’s Rock and Roll Forever Foundation, and author Ken Korber’s Center for Functional Learning, the book also features an accompanying lesson plan that engages the youngest learners in a fun, music-filled “STEAM” (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Math) project. Grace’s Rockin’ Roll Adventure is currently being piloted in TeachRock Partner Schools and select school systems in New York, New Jersey, California, and Illinois. In the book, the 9th in the Musical Adventures of Grace Series, Grace and her classmates win a contest to attend a Little Steven and the Disciples of Soul concert—a realistic plot considering that during his 2018 Teacher Solidarity Tour, Van Zandt gifted tickets to nearly 10,000 students and teachers nationwide. Invigorated by the music, Grace approaches Van Zandt, who bequeaths an instrument, setting the young musician on a rock and roll adventure with her classmates. In the accompanying workbook, real-life students learn about the various shapes in guitar designs, and ultimately combine music, math, art, and geometry to create a two- dimensional instrument of their own. -

Masterpiece Theatre – the First 35 Years – 1971-2006

Masterpiece Theatre The First 35 Years: 1971-2006 Season 1: 1971-1972 The First Churchills The Spoils of Poynton Henry James The Possessed Fyodor Dostoyevsky Pere Goriot Honore de Balzac Jude the Obscure Thomas Hardy The Gambler Fyodor Dostoyevsky Resurrection Leo Tolstoy Cold Comfort Farm Stella Gibbons The Six Wives of Henry VIII ▼ Keith Michell Elizabeth R ▼ [original for screen] The Last of the Mohicans James Fenimore Cooper Season 2: 1972-1973 Vanity Fair William Makepeace Thackery Cousin Bette Honore de Balzac The Moonstone Wilkie Collins Tom Brown's School Days Thomas Hughes Point Counter Point Aldous Huxley The Golden Bowl ▼ Henry James Season 3: 1973-1974 Clouds of Witness ▼ Dorothy L. Sayers The Man Who Was Hunting Himself [original for the screen] N.J. Crisp The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club Dorothy L. Sayers The Little Farm H.E. Bates Upstairs, Downstairs, I John Hawkesworth (original for tv) The Edwardians Vita Sackville-West Season 4: 1974-1975 Murder Must Advertise ▼ Dorothy L. Sayers Upstairs, Downstairs, II John Hawkesworth (original for tv) Country Matters, I H.E. Bates Vienna 1900 Arthur Schnitzler The Nine Tailors Dorothy L. Sayers Season 5: 1975-1976 Shoulder to Shoulder [documentary] Notorious Woman Harry W. Junkin Upstairs, Downstairs, III John Hawkesworth (original for tv) Cakes and Ale W. Somerset Maugham Sunset Song James Leslie Mitchell Season 6: 1976-1977 Madame Bovary Gustave Flaubert How Green Was My Valley Richard Llewellyn Five Red Herrings Dorothy L. Sayers Upstairs, Downstairs, IV John Hawkesworth (original for tv) Poldark, I ▼ Winston Graham Season 7: 1977-1978 Dickens of London Wolf Mankowitz I, Claudius ▼ Robert Graves Anna Karenina Leo Tolstoy Our Mutual Friend Charles Dickens Poldark, II ▼ Winston Graham Season 8: 1978-1979 The Mayor of Casterbridge ▼ Thomas Hardy The Duchess of Duke Street, I ▼ Mollie Hardwick Country Matters, II H.E. -

The Importance of the Weimar Film Industry Redacted for Privacy Abstract Approved: Christian P

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Tamara Dawn Goesch for the degree of Master of Arts in Interdisciplinary Studies in Foreign Languages and Litera- tures (German), Business, and History presented on August 12, 1981 Title: A Critique of the Secondary Literature on Weimar Film; The Importance of the Weimar Film Industry Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: Christian P. Stehr Only when all aspects of the German film industry of the 1920's have been fully analyzed and understood will "Weimar film" be truly comprehensible. Once this has been achieved the study of this phenomenon will fulfill its po- tential and provide accurate insights into the Weimar era. Ambitious psychoanalytic studies of Weimar film as well as general filmographies are useful sources on Wei- mar film, but the accessible works are also incomplete and even misleading. Theories about Weimar culture, about the group mind of Weimar, have been expounded, for example, which are based on limited rather than exhaustive studies of Weimar film. Yet these have nonetheless dominated the literature because no counter theories have been put forth. Both the deficiencies of the secondary literature and the nature of the topic under study--the film media--neces- sitate that attention be focused on the films themselves if the mysteries of the Weimar screenare to be untangled and accurately analyzed. Unfortunately the remnants of Weimar film available today are not perfectsources of information and not even firsthand accounts in othersour- ces on content and quality are reliable. However, these sources--the films and firsthand accounts of them--remain to be fully explored. They must be fully explored if the study of Weimar film is ever to advance. -

Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films

Gesticulated Shakespeare: Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Rebecca Collins, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Alan Woods, Advisor Janet Parrott Copyright by Jennifer Rebecca Collins 2011 Abstract The purpose of this study is to dissect the gesticulation used in the films made during the silent era that were adaptations of William Shakespeare's plays. In particular, this study investigates the use of nineteenth and twentieth century established gesture in the Shakespearean film adaptations from 1899-1922. The gestures described and illustrated by published gesture manuals are juxtaposed with at least one leading actor from each film. The research involves films from the experimental phase (1899-1907), the transitional phase (1908-1913), and the feature film phase (1912-1922). Specifically, the films are: King John (1899), Le Duel d'Hamlet (1900), La Diable et la Statue (1901), Duel Scene from Macbeth (1905), The Taming of the Shrew (1908), The Tempest (1908), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1909), Il Mercante di Venezia (1910), Re Lear (1910), Romeo Turns Bandit (1910), Twelfth Night (1910), A Winter's Tale (1910), Desdemona (1911), Richard III (1911), The Life and Death of King Richard III (1912), Romeo e Giulietta (1912), Cymbeline (1913), Hamlet (1913), King Lear (1916), Hamlet: Drama of Vengeance (1920), and Othello (1922). The gestures used by actors in the films are compared with Gilbert Austin's Chironomia or A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery (1806), Henry Siddons' Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action; Adapted to The English Drama: From a Work on the Subject by M.