The Effects of Online and Social Media Marketing on the Editorial Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lai CV April 24 2018 Ucalg For

THE UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Curriculum Vitae Date: April 2018 1. SURNAME: Lai FIRST NAME: Larissa MIDDLE NAME(S): -- 2. DEPARTMENT/SCHOOL: English 3. FACULTY: Arts 4. PRESENT RANK: Associate Professor/ CRC II SINCE: 2014 5. POST-SECONDARY EDUCATION University or Institution Degree Subject Area Dates University of Calgary PhD English 2001 - 2006 University of East Anglia MA Creative Writing 2000 - 2001 University of British Columbia BA (Hon.) Sociology 1985 - 1990 Title of Dissertation and Name of Supervisor Dissertation: The “I” of the Storm: Practice, Subjectivity and Time Zones in Asian Canadian Writing Supervisor: Dr. Aruna Srivastava 6. EMPLOYMENT RECORD (a) University, Company or Organization Rank or Title Dates University of Calgary, Department of English Associate Professor/ CRC 2014-present II in Creative Writing University of British Columbia, Department of English Associate Professor 2014-2016 (on leave) University of British Columbia, Department of English Assistant Professor 2007-2014 University of British Columbia, Department of English SSHRC Postdoctoral 2006-2007 Fellow Simon Fraser University, Department of English Writer-in-Residence 2006 University of Calgary, Department of English Instructor 2005 University of Calgary, Department of Communications Instructor 2004 Clarion West, Science Fiction Writers’ Workshop Instructor 2004 University of Calgary, Department of Communications Teaching Assistant 2002-2004 University of Calgary, Department of English Teaching Assistant 2001-2002 Writers for Change, Asian Canadian Writers’ -

Words Like That: Reading, Writing, and Sadomasochism

WORDS LIKE THAT: READING, WRITING, AND SADOMASOCHISM JORDANA M. GREENBLATT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN ENGLISH YORK UNIVERSITY, TORONTO, ONTARIO APRIL 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothgque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'6dition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-68344-6 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-68344-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Biblioth&que et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

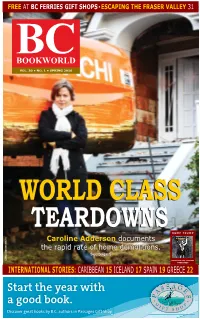

Spring 2016 Volume 30

FREE AT BC FERRIES GIFT SHOPS • ESCAPING THE FRASER VALLEY 31 BC BOOKWORLD VOL. 30 • NO. 1 • SPRING 2016 WORLDWORLD CLASSCLASS TEARDOWNSTEARDOWNS DUMP TRUMP Caroline Adderson documents the rapid rate of home demolitions. See page 5 LAURA SAWCHUK PHOTO PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40010086 INTERNATIONAL STORIES: CARIBBEAN 15 ICELAND 17 SPAIN 19 GREECE 22 Start the year with a good book. Discover great books by B.C. authors in Passages Gift Shop JOIN US May 20th - 22nd, 2016 Prestige Harbourfront Resort Your coaches Salmon Arm, BC and mentors for 2016: A Festival Robert J. Sawyer $3,000 designed by writers Susan Fox IN CASH for writers Ted Bishop Arthur Slade to encourage, support, Joëlle Anthony inspire and inform. Richard Wagamese Bring your muse Victor Anthony and expect to be Michael Slade Jodi McIsaac welcomed, included Alyson Quinn and thoroughly Jodie Renner entertained. Howard White Alan Twigg Bernie Hucul 3 CATEGORIES | 3 CASH PRIZES | ONE DEADLINE FICTION – MAXIMUM 3,000 WORDS CREATIVE NON-FICTION – MAXIMUM 4,000 WORDS on the POETRY – SUITE OF 5 RELATED POEMS Lake DEADLINE FOR ENTRIES: MAY 15, 2016 Writers’ Festival SUBMIT ONLINE: www.subterrain.ca INFO: [email protected] Find out what these published authors and ENTRY FEE: industry professionals can do for you. Register at: $2750 INCLUDES A ONE-YEAR SUBTERRAIN SUBSCRIPTION! www.wordonthelakewritersfestival.com PER ENTRY YOU MAY SUBMIT AS MANY ENTRIES IN AS MANY CATEGORIES AS YOU LIKE “I have attended this conference for Faculty: the past four years. The information is Alice Acheson -

Asper Nation Other Books by Marc Edge

Asper Nation other books by marc edge Pacific Press: The Unauthorized Story of Vancouver’s Newspaper Monopoly Red Line, Blue Line, Bottom Line: How Push Came to Shove Between the National Hockey League and Its Players ASPER NATION Canada’s Most Dangerous Media Company Marc Edge NEW STAR BOOKS VANCOUVER 2007 new star books ltd. 107 — 3477 Commercial Street | Vancouver, bc v5n 4e8 | canada 1574 Gulf Rd., #1517 | Point Roberts, wa 98281 | usa www.NewStarBooks.com | [email protected] Copyright Marc Edge 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (access Copyright). Publication of this work is made possible by the support of the Canada Council, the Government of Canada through the Department of Cana- dian Heritage Book Publishing Industry Development Program, the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit. Printed and bound in Canada by Marquis Printing, Cap-St-Ignace, QC First printing, October 2007 library and archives canada cataloguing in publication Edge, Marc, 1954– Asper nation : Canada’s most dangerous media company / Marc Edge. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-1-55420-032-0 1. CanWest Global Communications Corp. — History. 2. Asper, I.H., 1932–2003. I. Title. hd2810.12.c378d34 2007 384.5506'571 c2007–903983–9 For the Clarks – Lynda, Al, Laura, Spencer, and Chloe – and especially their hot tub, without which this book could never have been written. -

By Carellin Brooks

Carellin Brooks was born in Vancouver in 1970. She has lived in Ottawa, Montreal, New York, Oxford and London (UK), San Diego, Seattle, Japan, and Salt Lake City. She holds a BA from McGill and, as you will read, is working toward a DPhil from Oxford. She is the managing editor at New Star Books in Vancouver and an instructor at University of British Columbia. Rhodekill: She tried to put Oxford behind her…to no avail Carellin Brooks I first heard about the Rhodes Scholarship when a woman in one of my undergraduate classes in Canada was introduced to us all as having won one. She smiled modestly; she was a quiet- looking person overall, devoid of makeup and the opposite of flashy. I am embarrassed to admit I looked her over and thought, “Well, if she can do it, so can I.” I was a brash young thing in those days, all attitude and platinum hair cut to an inch. I had grown up in the foster-care system and was a pet of the agency back in my hometown which bankrolled my studies. The director of the agency took a personal interest in my application and woke me at seven one morning with a phone call. “Fencing.” “Wha…?” “Fencing. I’ve been thinking it over. You need a sport.” Aside from aerobics in high school, my athletic experience consisted of breaking my glasses on fly balls, being chosen last for elementary- school teams and, in confirmation of the wisdom of this, scoring goals for the opposing team. “Fencing’s really esoteric,” he continued, “so it won’t stick out that you’re not very athletic.” It was a good idea but in the end my athletic credentials consisted of my hour-long daily walk to school. -

Chuck Davis Continued from Page 4

Vancouver Historical Society NEWSLETTER ISSN 0042 - 2487 October 2010 Vol. 50 No. 2 Wreck Beach October Speaker: Carellin Brooks pproximately 500,000 people history of this fascinating stretch of In case you were wondering: Avisit Wreck Beach every year, coast. The area has been in threat since this presentation is an academic and despite an absence of access before its inception, and not always examination of the geographic roads for clean-up or maintenance, for the reasons you’d think. Erosion, and cultural history of this iconic minimal police or security coverage, UBC expansion, arrests and ill-judged Vancouver location. Please be assured and a highly-desirable location for attempts at preservation are just some the accompanying images will be residential development, it remains of the situations Wreck Beach faced no more prurient than what one one of the down to become cleanest, what it is today. naturally pristine beaches of In the end, the the city. The story of Wreck enthusiastic Beach is an and vigilant examination of attention of the freedom, and Wreck Beach the variations of Preservation what freedom Society is a means to clear example of different people what an engaged or groups. citizenry can accomplish. Carellin The Society’s was born in commitment Vancouver, to keeping and has lived Wreck Beach in Ottawa, untarnished is Montreal, New reflected in its York, Oxford resistance to outside regulation and and London (UK), San Diego, Seattle, Author Carellin Brooks emphasis on self-policing. But it has Japan, and Salt Lake City. She has not been without struggle. a BA from McGill University and might find in the collection of any a Masters from Oxford University. -

The Function of the Minimum Wage in the Neoliberal

Responding to the Crisis of Profitability: The Function of the Minimum Wage in the Neoliberal Era by Jason Edwards B.A., University of New Brunswick, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Academic Unit of Political Science Supervisor: Thom Workman, PhD, Political Science Examiners: David Bedford, PhD, Political Science William Parenteau, PhD, History This thesis is accepted by the Dean of Graduate Studies THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW BRUNSWICK May, 2011 ©Jason Edwards, 2011 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du 1+1Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91812-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91812-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Distilling the Canadian Copyright Review 2018: One Publisher’S Path Through Canadian Copyright and Canadian Coursepacks

Distilling the Canadian Copyright Review 2018: One Publisher’s Path Through Canadian Copyright and Canadian Coursepacks by Anumeha Gokhale M.B.A, Goa Institute of Management, India, 2010 Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Publishing in the Publishing Program Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology © Anumeha Gokhale 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2018 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Approval Name: Anumeha Gokhale Degree: Master of Publishing Title of Project: Distilling the Canadian Copyright Review 2018: One Publisher’s Path Through Canadian Copyright and Canadian Coursepacks Supervisory Committee: Suzanne Norman Senior Supervisor Lecturer, SFU Publishing Program ____________________________ Hannah McGregor Second Reader Assistant Professor, Publishing Program ____________________________ Robert Ballantyne Industry Supervisor Associate Publisher and Vice President Arsenal Pulp Press, Vancouver, British Columbia ____________________________ Date Defended/Approved: 17 December 2018 ii Abstract This report examines the current academic publishing market in the light of the ongoing Statutory Review of Copyright Act of Canada (2018), and reconciles the testimonies presented before the review committee by the industry stakeholders. It focuses on the impact on academic publishing since the Copyright Modernization Act (2012) came into effect, which resulted -

Armchair Books and Penguin Random House Welcome These Authors to the Whistler Readers and Writers Festival

Welcome Welcome to the 14th annual Whistler Writers Festival. Each year we strive to bring the very best Canadian and international authors to Whistler for a weekend packed with readings, workshops, and opportunities for you to meet some of your favourite authors. This year our theme is fledgling to flight, which celebrates our ongoing commitment to feature both emerging and established authors on the same stage, each showcasing and supporting the other. Thursday October 15th will feature Comedy Quickies, a night of bite-sized comedy that takes writers’ humorous humdingers to the stage. A panel of judges will pre-select their 10 favourite written submissions to bring to life in the beautiful Millennium Place Theatre. Cash and prizes will be awarded for Best Comedy Writing, and of course, The People’s Choice award (chosen by our audience) will go to the best act of the evening. Our special guest will be comedian, humourist and author, Charlie Demers from CBC’s The Debaters and This is That. On Friday night our Chefs’ Reception will feature star chefs Emily Wight (Well Fed, Flat Broke) and award-winning poet and author Susan Musgrave (A Taste of Haida Gwaii). James Nevison, prize-winning author of the best selling book, (Had A Glass 2015) will join in to talk about some of the best and least expensive wine pairings. There will be samples of appetizers to try and you’ll be able to meet all three authors and hear them discuss their featured recipes and books. The Reception will be followed by the Literary Cabaret. -

Rights Catalogue 2017

adventures in literary publishing since 2004 BookThugBookThug www.bookthug.ca | publishing the future of literature Rights Catalogue 2017 Untitled-3 1 2017-03-09 5:18 PM B BOOKTHUG It’s been said in certain circles that BookThug is the literary party that everyone wants to be at. Celebrating adventures in literary publishing since 2004, BookThug is best known for their contemporary and engaging works of fiction, nonfiction, poetry, drama and literary translation, by both emerging and established authors from Canada and around the world. BookThug Canadian Distributor: 260 Ryding Avenue LitDistCo Toronto, Ontario 8300 Lawson Rd. Canada M6N 1H5 Milton, Ontario Canada L9T 0A4 bookthug.ca 1 800 591 6250 [email protected] Jay Millar, Publisher [email protected] U.S. Distributor: +1 416 994 5804 Small Press Distribution 1341 Seventh Street Hazel Millar, Publisher Berkeley, California [email protected] 94710-1409 +1 416 994 1891 1 800 869 7553 [email protected] @bookthug Rights Agent facebook/bookthug Kelvin Kong, The Rights Factory P.O. Box 499, Station C bookthug_press Toronto, Ontario Canada M6J 3P6 +1 416 966 5367 [email protected] therightsfactory.com FICTION Blood Fable by Oisín Curran The Third Person by Emily Anglin Sludge Utopia by Catherine Fatima Double Teenage by Joni Murphy Rich and Poor by Jacob Wren One Hundred Days of Rain by Carellin Brooks Involuntary Bliss by Devon Code Giving Up by Mike Steeves Pauls by Jess Taylor Polyamorous Love Song by Jacob Wren A by André Alexis Fiction Blood Fable Oisín Curran Maine, 1980. A utopian community is on the verge of collapse. -

Book*Hug Spring 2015 Catalogue

BOOKTHUG SPRING 2015 Adventures in Literary Publishing since 2004 www.bookthug.ca | publishing the future of literature a message from the head thug As we built this catalogue it came to us what an absolutely Pearl Pirie and Lesley Battler, both new to BookThug and fabulous lineup of books we have for Spring 2015. Of course, whose manuscripts were chosen by our poetry editor Phil we knew they were great books when we acquired them – Hall, provide exciting new collections to sink into. Pirie’s vibrant, exciting, and playfully challenging titles that would the pet radish, shrunken will envelop readers with its quirky appeal to a wide array of readers. Each of these works joins lyricism and wit, while Battler’s Endangered Hydrocarbons in our already existing family of diverse books so well, we explores the inescapable world we live in as controlled by big think you’ll agree that they represent a unique contribution oil – even poets and poetry are not safe from that tar pool. to the diversity that defines our publishing program. The Clown Princes of Canadian Poetry (Interior BC With no other publishing house will you find a selection Chapter) known as Jake Kennedy and kevin mcpherson of books as diverse as those that make up our Spring 2015 eckhoff offer readers two very different books: Kennedy’s schedule – representing a cross-range of poetry, fiction, and lyrical collection Merz Structure No. 2 Burnt by Children entre-genre categories, on subject matter as distinctive as the at Play treats destruction as creation and the destroyed writers themselves: with a sense of beauty and creativity, and reframes how we think about loss; Eckhoff’s Their Biography: a organism of First up are two fantiastic titles chosen by our fiction editor relations hips was written by anyone but kevin, and yet he Malcolm Sutton. -

Writing for the Reluctant Reader Losing Her Voice: a Writer

WRITE THE MAGAZINE OF THE WRITERS’ UNION OF VOLUME 42 NUMBER 3 CANADA WINTER 2015 Writing for the Reluctant Reader 8 Losing Her Voice: A Writer Struggles with a First Novel and a Dying Sister 10 The Authors’ Fest: Tips and Tricks From a Festival Insider 15 tbooks by Vivek 3 Shraya � CResidencies for Creative SHE OF THE MOUNTAINS A Globe and Mail “Globe 100” of 2014 and Cultural Exploration “A lyrical ode to love in all its many forms.” Creative spaces and —Publishers Weekly accommodation in a community and heritage setting Artists • Writers • Cultural Researchers GOD LOVES HAIR A Quill and Quire Best Book of 2014 “A moving and ultimately joyous portrait of growing up and the resiliency of youth.” 3401 Pleasant Valley Road —Canadian Children’s Book Centre Vernon, British Columbia, Canada V1T 4L4 arsenal pulp press arsenalpulp.com 250-275-1525 www.caetani.ca JOIN A HEALTH PLAN THAT’S EXCLUSIVE TO THE CANADIAN THE PLAN IS A SERVICE OF AFBS, A NOT-FOR-PROFIT INSURER WRITING COMMUNITY. IT’S EASY TO UNDERSTAND, AND COVERAGE IS GUARANTEED. CALL 1-800-387-8897 EXT. 238 OR EMAIL [email protected] TO LEARN MORE. From the Chair By Harry Thurston We are trying something new this winter in adapting our operations to the Digital Age. Instead of bringing National Council members together in Toronto for our January meeting, colleagues of the need for action, and to do so he needs the numbers. To that end we will be circulating an income survey in from all corners of this vast, snowbound country, the New Year to make our case for just how much worse things we are going to conduct our business remotely.