Tropical Synoptic Meteorology – Gary M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Responses of the Hydrological Cycle to Solar Forcings

1 Responses of the hydrological cycle to solar forcings Jane Smyth Advised by Dr. Trude Storelvmo Second Reader Dr. William Boos May 6, 2016 A Senior Thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, in partial fulfillment of the Bachelor’s Degree. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the Bachelor’s Degree from the Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, I agree that the department may make copies or post it on the departmental website so that others may better understand the undergraduate research of the de- partment. I further agree that extensive copying of this thesis is allowable only for scholarly purposes. It is understood, however, that any copying or publication of this thesis for commercial purposes or financial gain is not allowed without my written consent. Jane Elizabeth Smyth, 6 May, 2016 RESPONSESOFTHE HYDROLOGICALCYCLETOjane smyth SOLARFORCINGS Senior Thesis advised by dr. trude storelvmo 1 Chapter I: Solar Geoengineering 4 contents1.1 Abstract . 4 1.2 Introduction . 5 1.2.1 Solar Geoengineering . 5 1.2.2 The Hydrological Cycle . 5 1.3 Models & Methods . 7 1.4 Results and Discussion . 9 1.4.1 Thermodynamic Scaling of Net Precipitation . 9 1.4.2 Dynamically Driven Precipitation . 12 1.4.3 Relative Humidity . 12 1.5 Conclusions . 14 1.6 Appendix . 16 2 Chapter II: Orbital Precession 22 2.1 Abstract . 22 2.2 Introduction . 23 2.3 Experimental Design & Methods . 24 2.3.1 Atmospheric Heat Transport . 25 2.3.2 Hadley Circulation . 25 2.3.3 Gross Moist Stability . -

Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i: Nā Makani

November 19, 2012 Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai‘i: Nā Makani Mau Steven Businger & Sara da Silva [email protected], [email protected] Iasona Ellinwood, [email protected] Pauline W. U. Chinn, [email protected] University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Figure 1. Schematic of global circulation Grades: 6-8, modifiable for 9-12 Time: 2 - 10 hours Nā Honua Mauli Ola, Guidelines for Educators, No Nā Kumu: Educators are able to sustain respect for the integrity of one’s own cultural knowledge and provide meaningful opportunities to make new connections among other knowledge systems (p. 37). Standard: Earth and Space Science 2.D ESS2D: Weather and Climate Weather varies day to day and seasonally; it is the condition of the atmosphere at a given place and time. Climate is the range of a region’s weather over one to many years. Both are shaped by complex interactions involving sunlight, ocean, atmosphere, latitude, altitude, ice, living things, and geography that can drive changes over multiple time scales—days, weeks, and months for weather to years, decades, centuries, and beyond for climate. The ocean absorbs and stores large amounts of energy from the sun and releases it slowly, moderating and stabilizing global climates. Sunlight heats the land more rapidly. Heat energy is redistributed through ocean currents and atmospheric circulation, winds. Greenhouse gases absorb and retain the energy radiated from land and ocean surfaces, regulating temperatures and keep Earth habitable. (A Framework for K-12 Science Education, NRC, 2012) Hawai‘i Content and Performance Standards (HCPS) III http://standardstoolkit.k12.hi.us/index.html 1 November 19, 2012 Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i STRAND THE SCIENTIFIC PROCESS Standard 1: The Scientific Process: SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION: Discover, invent, and investigate using the skills necessary to engage in the scientific process Benchmarks: SC.8.1.1 Determine the link(s) between evidence and the Topic: Scientific Inquiry conclusion(s) of an investigation. -

Link Between the Double-Intertropical Convergence Zone Problem and Cloud Biases Over the Southern Ocean

Link between the double-Intertropical Convergence Zone problem and cloud biases over the Southern Ocean Yen-Ting Hwang1 and Dargan M. W. Frierson Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-1640 Edited by Mark H. Thiemens, University of California at San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved February 15, 2013 (received for review August 2, 2012) The double-Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) problem, in which climate models show that the bias can be reduced by changing excessive precipitation is produced in the Southern Hemisphere aspects of the convection scheme (e.g., refs. 7–9) or changing the tropics, which resembles a Southern Hemisphere counterpart to the surface wind stress formulation (e.g., ref. 10). Given the complex strong Northern Hemisphere ITCZ, is perhaps the most significant feedback processes in the tropics, it is challenging to understand and most persistent bias of global climate models. In this study, we the mechanisms by which the sensitivity experiments listed above look to the extratropics for possible causes of the double-ITCZ improve tropical precipitation. problem by performing a global energetic analysis with historical Recent work in general circulation theory has suggested that simulations from a suite of global climate models and comparing one should not only look within the tropics for features that affect with satellite observations of the Earth’s energy budget. Our results tropical precipitation. A set of idealized experiments showed that show that models with more energy flux into the Southern heating a global climate model exclusively in the extratropics can Hemisphere atmosphere (at the top of the atmosphere and at the lead to tropical rainfall shifts from one side of the tropics to the surface) tend to have a stronger double-ITCZ bias, consistent with other (11). -

Tropical Weather Discussion

TROPICAL WEATHER DISCUSSION • Purpose The Tropical Weather Discussion describes major synoptic weather features and significant areas of disturbed weather in the tropics. The product is intended to provide current weather information for those who need to know the current state of the atmosphere and expected trends to assist them in their decision making. The product gives significant weather features, areas of disturbed weather, expected trends, the meteorological reasoning behind the forecast, model performance, and in some cases a degree of confidence. • Content The Tropical Weather Discussion is a narrative explaining the current weather conditions across the tropics and the expected short-term changes. The product is divided into four different sections as outline below: 1. SPECIAL FEATURES (event-driven) The special features section includes descriptions of hurricanes, tropical storms, tropical depressions, subtropical cyclones, and any other feature of significance that may develop into a tropical or subtropical cyclone. For active tropical cyclones, this section provides the latest advisory data on the system. Associated middle and upper level interactions as well as significant clouds and convection are discussed with each system. This section is omitted if none of these features is present. 2. TROPICAL WAVES (event-driven) This section provides a description of the strength, position, and movement of all tropical waves analyzed on the surface analysis, from east to west. A brief reason for a wave’s position is usually given, citing surface observations, upper air time sections, satellite imagery, etc. The associated convection is discussed with each tropical wave as well as any potential impacts to landmasses or marine interests. -

Change of the Tropical Hadley Cell Since 1950

Change of the Tropical Hadley Cell Since 1950 Xiao-Wei Quan, Henry F. Diaz, and Martin P. Hoerling NOAA-CIRES Climate Diagnostic Center, Boulder, Colorado, USA last revision: March 24, 2004 Abstract The change in the tropical Hadley cell since 1950 is examined within the context of the long-term warming in the global surface temperatures. The study involves analyses of observations, including various metrics of Hadley cell, and ensemble 50-year simulations by an atmospheric general circulation model forced with the observed evolution of global sea surface temperature since 1950. Consistent evidence is found for an intensification of the Northern Hemisphere winter Hadley cell since 1950. This is shown to be an atmospheric response to the observed tropical ocean warming trend, together with an intensification in El Niño’s interannual fluctuations including larger amplitude and increased frequency after 1976. The intensification of the winter Hadley cell is shown to be associated with an intensified hydrological cycle consisting of increased equatorial oceanic rainfall, and a general drying of tropical/subtropical landmasses. This Hadley cell change is consistent with previously documented dynamic changes in the extratropics, including a strengthening of westerly atmospheric flow and an intensification of midlatitude cyclones. 1. Introduction The tropical Hadley cell, by definition, is the zonal mean meridional mass circulation in the atmosphere bounded roughly by 30ºS and 30ºN. It is characterized by equatorward mass transport by the prevailing trade wind flow in the lower troposphere, and poleward mass transport in the upper troposphere. This lateral mass circulation links the mean ascending motion in the equatorial zone with subsidence in the subtropics, and represents a major part of the large-scale meridional overturning between tropics and subtropics. -

ESSENTIALS of METEOROLOGY (7Th Ed.) GLOSSARY

ESSENTIALS OF METEOROLOGY (7th ed.) GLOSSARY Chapter 1 Aerosols Tiny suspended solid particles (dust, smoke, etc.) or liquid droplets that enter the atmosphere from either natural or human (anthropogenic) sources, such as the burning of fossil fuels. Sulfur-containing fossil fuels, such as coal, produce sulfate aerosols. Air density The ratio of the mass of a substance to the volume occupied by it. Air density is usually expressed as g/cm3 or kg/m3. Also See Density. Air pressure The pressure exerted by the mass of air above a given point, usually expressed in millibars (mb), inches of (atmospheric mercury (Hg) or in hectopascals (hPa). pressure) Atmosphere The envelope of gases that surround a planet and are held to it by the planet's gravitational attraction. The earth's atmosphere is mainly nitrogen and oxygen. Carbon dioxide (CO2) A colorless, odorless gas whose concentration is about 0.039 percent (390 ppm) in a volume of air near sea level. It is a selective absorber of infrared radiation and, consequently, it is important in the earth's atmospheric greenhouse effect. Solid CO2 is called dry ice. Climate The accumulation of daily and seasonal weather events over a long period of time. Front The transition zone between two distinct air masses. Hurricane A tropical cyclone having winds in excess of 64 knots (74 mi/hr). Ionosphere An electrified region of the upper atmosphere where fairly large concentrations of ions and free electrons exist. Lapse rate The rate at which an atmospheric variable (usually temperature) decreases with height. (See Environmental lapse rate.) Mesosphere The atmospheric layer between the stratosphere and the thermosphere. -

Hadley's Principle: Understanding and Misunderstanding the Trade

History of Meteorology 3 (2006) 17 Hadley’s Principle: Understanding and Misunderstanding the Trade Winds Anders O. Persson Department for research and development Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute SE 601 71 Norrköping, Sweden [email protected] Old knowledge will often be rediscovered and presented under new labels, causing much confusion and impeding progress—Tor Bergeron.1 Introduction In May 1735 a fairly unknown Englishman, George Hadley, published a groundbreaking paper, “On the Cause of the General Trade Winds,” in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. His path to fame was long and it took 100 years to have his ideas accepted by the scientific community. But today there is a “Hadley Crater” on the moon, the convectively overturning in the tropics is called “The Hadley Cell,” and the climatological centre of the UK Meteorological Office “The Hadley Centre.” By profession a lawyer, born in London, George Hadley (1685-1768) had in 1735 just became a member of the Royal Society. He was in charge of the Society’s meteorological work which consisted of providing instruments to foreign correspondents and of supervising, collecting and scrutinizing the continental network of meteorological observations2. This made him think about the variations in time and geographical location of the surface pressure and its relation to the winds3. Already in a paper, possibly written before 1735, Hadley carried out an interesting and far-sighted discussion on the winds, which he found “of so uncertain and variable nature”: Hadley’s Principle 18 …concerning the Cause of the Trade-Winds, that for the same Cause the Motion of the Air will not be naturally in a great Circle, for any great Space upon the surface of the Earth anywhere, unless in the Equator itself, but in some other Line, and, in general, all Winds, as they come nearer the Equator will become more easterly, and as they recede from it, more and more westerly, unless some other Cause intervene4. -

Atmospheric Circulation

Atmospheric circulation Trade winds http://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2002/10apr_hawaii/ Atmosphere (noun) the envelope of gases (air) surrounding the earth or another planet Dry air: Argon, 0.98% O2, 21% N2, 78% CO2, >400ppm & rising Water vapor can be up to 4% 50% below 5.6 km (18,000 ft) 90% below 16 km (52,000 ft) http://mychinaviews.com/2011/06/into-thin-air.html Drivers of atmospheric circulation Uneven solar heating At poles sun’s energy is spread over a larger region Uneven solar heating At poles sun’s energy is spread over a larger region Uneven solar heating At poles sun’s energy is spread over a larger region Ways to transfer heat Conduction: Transfer of heat by direct contact. Heat goes from warmer areas to colder areas. Ways to transfer heat Radiation: Any object radiates heat as electromagnetic radiation (light, infrared) based on temperature of the object. Ways to transfer heat Convection: Heat carried by a fluid (air, water, etc) from a region of high temperature to a region of lower temperature. Convection cell Warm air rises, then as it cools it sinks back down Thermal (heat) balance Heat in = Heat out, for earth as a whole ! Heat in = Heat out, for latitude bands " Heat out t r o p s n a r Heat in t t a e h t e N RedistributionIncreasing heat of heat drive atmospheric circulation So, might expect Cool air sinking near the poles Warm air rising at equator Lutgens and Tarbuk, 2001 http://www.ux1.eiu.edu/~cfjps/1400/circulation.html Turns out a 3 cell modelis better Polar cell Ferrel cell (Mid-latitude -

ESCI 344 – Tropical Meteorology Lesson 3 – General Circulation of the Tropics

ESCI 344 – Tropical Meteorology Lesson 3 – General Circulation of the Tropics References: Forecaster’s Guide to Tropical Meteorology (updated), Ramage Climate Dynamics of the Tropics, Hastenrath Tropical Climatology (2nd ed), McGregor and Nieuwolt Tropical Meteorology, Tarakanov Climate and Weather in the Tropics, Riehl General Circulation of the Tropical Atmosphere, Vol II, Newell et al. “The South Pacific Convergence Zone (SPCZ): A Review”, Vincent, Mon.Wea. Rev., 122, 1949-1970, 1994 “The Central Pacific Near-Equatorial Convergence Zone”, Ramage, J. Geophys. Res., 86, 6580-6598 Reading: Introduction to the Meteorology and Climate of the Tropics, Chapter 3 Vincent, “The SPCZ: A Review” Lau and Yang, “Walker Circulation” James, “Hadley Circulation” Waliser, “Intertropical Convergence Zones” Hastenrath, “Tropical Climates” Madden, “Intraseasonal Oscillation (MJO)” TERMINOLOGY Boreal refers to the Northern Hemisphere Austral refers to the Southern Hemisphere LATITUDINAL HEAT IMBALANCE Net radiation flux is defined as the difference in incoming radiation flux and outgoing radiation flux. A positive net radiation flux indicates a surplus of energy, while a negative net radiation flux indicates a deficit. This figure shows the longitudinally-averaged, annual-mean radiation fluxes at the top of the atmosphere. Outgoing shortwave is due to scattering and reflection. Net shortwave is the difference between the incoming and outgoing shortwave radiation. When the earth-atmosphere system is considered as a whole, there is a positive net radiation flux between about 40N and 40S, while there is a negative net radiation flux poleward of 40 in both hemispheres. In order for a steady-state temperature to be achieved, there must be transport of heat from the earth’s surface to the atmosphere, and from the tropics to the polar regions. -

Synoptic Meteorology

Lecture Notes on Synoptic Meteorology For Integrated Meteorological Training Course By Dr. Prakash Khare Scientist E India Meteorological Department Meteorological Training Institute Pashan,Pune-8 186 IMTC SYLLABUS OF SYNOPTIC METEOROLOGY (FOR DIRECT RECRUITED S.A’S OF IMD) Theory (25 Periods) ❖ Scales of weather systems; Network of Observatories; Surface, upper air; special observations (satellite, radar, aircraft etc.); analysis of fields of meteorological elements on synoptic charts; Vertical time / cross sections and their analysis. ❖ Wind and pressure analysis: Isobars on level surface and contours on constant pressure surface. Isotherms, thickness field; examples of geostrophic, gradient and thermal winds: slope of pressure system, streamline and Isotachs analysis. ❖ Western disturbance and its structure and associated weather, Waves in mid-latitude westerlies. ❖ Thunderstorm and severe local storm, synoptic conditions favourable for thunderstorm, concepts of triggering mechanism, conditional instability; Norwesters, dust storm, hail storm. Squall, tornado, microburst/cloudburst, landslide. ❖ Indian summer monsoon; S.W. Monsoon onset: semi permanent systems, Active and break monsoon, Monsoon depressions: MTC; Offshore troughs/vortices. Influence of extra tropical troughs and typhoons in northwest Pacific; withdrawal of S.W. Monsoon, Northeast monsoon, ❖ Tropical Cyclone: Life cycle, vertical and horizontal structure of TC, Its movement and intensification. Weather associated with TC. Easterly wave and its structure and associated weather. ❖ Jet Streams – WMO definition of Jet stream, different jet streams around the globe, Jet streams and weather ❖ Meso-scale meteorology, sea and land breezes, mountain/valley winds, mountain wave. ❖ Short range weather forecasting (Elementary ideas only); persistence, climatology and steering methods, movement and development of synoptic scale systems; Analogue techniques- prediction of individual weather elements, visibility, surface and upper level winds, convective phenomena. -

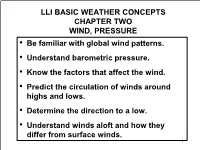

BASIC WEATHER CONCEPTS CHAPTER TWO WIND, PRESSURE • Be Familiar with Global Wind Patterns

LLI BASIC WEATHER CONCEPTS CHAPTER TWO WIND, PRESSURE • Be familiar with global wind patterns. • Understand barometric pressure. • Know the factors that affect the wind. • Predict the circulation of winds around highs and lows. • Determine the direction to a low. • Understand winds aloft and how they differ from surface winds. 1 EquatorPole Air Flow warm equatorial air rises, then moves to cooler mid-latitude regions then sinks 2 Mid-latitude High note each higher latitude region is colder until Pole is reached 3 What is a Hadley Cell? The Hadley cell, named after George Hadley, is a global scale tropical atmospheric circulation that features air rising near the equator, flowing poleward at 10–15 kilometers above the surface, descending in the subtropics, and then returning equatorward near the surface. This process maintains the Global Energy Balance preventing the equator from becoming hotter and polar regions becoming colder. 4 Global Highs and Lows 5 Global Winds 6 Video of Atmospheric Circulation • Global Atmospheric Circulation 1:54 mins. • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DHrapzH PCSA 7 European Explorers used Tradewinds St. Augustine >30˚ N > 30˚ S 9 Land Masses Modify Global Pattern 10 Key Points to Remember about Heat and Pressure • Heat: energy (heat) is always transferred from WARM to COLD • Pressure: pressure always flows from HIGH to LOW 11 Pressure Differences – HIGH pressure areas – like Hills – LOW pressure areas – like valleys Earth’s rotation causes winds to turn rather than travel straight from high to low 12 Winds around Highs and Lows highs-clockwise, lows counterclockwise 13 Movement of Air in Low Pressure and High Pressure Regions • Air molecules* move counterclockwise (in the Northern Hemisphere) and rise in a low pressure area. -

The Intertropical Convergence Zone of the Eastern Pacific Region (I)*

The Intertropical Convergence Zone of the Eastern Pacific Region (I)* MAJOR LEO ALPERT, A.C. Hq. AAF Weather Service, Asheville, N. C. INTRODUCTION Recently a large number of weather ob- servations have become available from air- ITTLE INFORMATION concerning the craft patrols in the Eastern Pacific Ocean structure and position of the inter- L between 90°W to 95°W Longitude, and 7°S tropical convergence zone in the East- to 14°N Latitude. From December 1941 to ern Pacific Ocean was available prior to the late 1944, hourly weather observations were war. As daily weather reports from ships made daily by patrol aircraft, flying between have never been numerous from this area, the Republic of Guatemala in Central Amer- all attempts to show the position of the ica, the Galapagos Archipelago and the main- intertropical convergence zone based upon land of Ecuador in South America. Data an interpretation of summarized ship re- for the period February 1942 to January ports are open to question. The charts pub- 1944 have been plotted on daily charts and lished in the " Atlas of Climatic Charts of analyzed by the author. the Oceans'n are probably the best of these The grand total of observations available for this region. They are based upon fre- from the aircraft patrols in the area from quencies of true-wind directions determined 10°N to 5°S for the period February 1942 by observing the effect of wind on the sea to January 1944, inclusive, is two to four surface from a moving ship at Greenwich times as great as the grand total of observa- Noon during the period 1885-1933.