Deanna Rusch* —Baseball Must Ascend and Aspire to the Highest Principles Œ of Integrity, of Professionalism, of Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sportsletter Interview: Shaun Assael

SportsLetter Interviews December 2007 Volume 18, No. 6 Shaun Assael With the recent release of the Mitchell Report, the story of steroids in Major League Baseball has dominated sports coverage. The report states, “Everyone involved in baseball over the past two decades — Commissioners, club officials, the Players Association, and the players — shares to some extent in the responsibility for the steroids era. There was a collective failure to recognize the problem as it emerged and deal with it early on.” For all the hand-wringing about Major League Baseball’s mea culpa, the use of anabolic steroids and other performance- enhancing drugs has been sports’ dirty little not-so-secret for decades. In his book, “Steroid Nation: Juiced Home Run Totals, Anti-aging Miracles, and a Hercules in Every High School: The Secret History of America’s True Drug Addiction” (ESPN Books), ESPN staff writer Shaun Assael traces the culture of steroids in sports. The tale is about as long as the sub-title of the book, and Assael chronicles the many twists of this complex story. He writes about the long-forgotten “visionaries” (like Dan Duchaine, author of the “Underground Steroid Handbook”), the athletes who became caught in cycles of steroid abuse (NFL star Lyle Alzado) and the research scientists charged to nab them (UCLA’s Dr. Don Catlin). The result is a panoramic view of steroids in America — a view that echoes the Mitchell Report in placing responsibility for the spread of performance-enhancing drugs on just about everyone including the media 1 ©1996-2008 LA84 Foundation. Reproduction of SportsLetter is encouraged with credit to the LA84 Foundation. -

Spring 2009 Issue of the University of Denver Sports and Entertainment

UNIVERSITY OF DENVER SPORTS AND ENTERTAINMENT LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 6 Spring 2009 CONTENTS LETTER FROM THE EDITOR …………………………………………………………………………………………………..2 ARTICLES MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL AND THE ANTITRUST RULE: WHERE ARE WE NOW? ………………………..3 Harvey Gilmore GREAT EXPECTATIONS: CONTENT REGULATION IN FILM, RADIO, AND TELEVISION…………………….31 Alexandra Gil “FROM RUSSIA” WITHOUT LOVE: CAN THE SHCHUKIN HEIRS RECOVER THEIR ANCESTOR’S ART COLLECTION?………………………………………………..…………………………………...65 Jane Graham OPPORTUNISM, UNCERTAINTY AND RELATIONAL CONTRACTING – ANTITRUST IN THE FILM INDUSTRY………………………………………………………………………………………107 Ryan M. Riegg SHOULD THE GOVERNMENT FLEX ITS MUSCLES AND REGULATE STEROIDS N BASEBALL? WEAKNESSES IN THE PUBLIC HEALTH ARGUMENT......………………………………………………………………151 Connor Williams SOUTH BY SOUTHWEST 2009 CLE CONFERENCE – WHERE TRENDY ENTERTAINMENT MEETS TRENDS IN ENTERTAINMENT LAW……………………...…………………………………………………..…186 Paul Tigan 1 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Dear Reader, Welcome to the Spring 2009 issue of the University of Denver Sports and Entertainment Law Journal. With this issue, we are excited to bring you insightful analysis and commentary focusing on a variety of legal topics within sports and entertainment law. Our goal is to provide compelling legal commentary on these industries, and with the hard work of our authors and editing staff, we are delighted to publish 6 articles presenting a variety of issues and perspectives. Anti-trust issues in Major League Baseball, government regulation of media content, and performance enhancing drugs in professional sports are among the topics our authors address in this edition of the Sports and Entertainment Law Journal. Additionally, a fellow law student from the University of Denver has written a review of the 2009 South-by-Southwest music and film conference. The students, professors, and practitioners of law that produce this commentary offer a valuable resource to our legal community. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

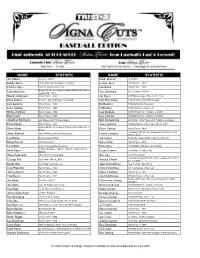

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

How Sports Help to Elect Presidents, Run Campaigns and Promote Wars."

Abstract: Daniel Matamala In this thesis for his Master of Arts in Journalism from Columbia University, Chilean journalist Daniel Matamala explores the relationship between sports and politics, looking at what voters' favorite sports can tell us about their political leanings and how "POWER GAMES: How this can be and is used to great eect in election campaigns. He nds that -unlike soccer in Europe or Latin America which cuts across all social barriers- sports in the sports help to elect United States can be divided into "red" and "blue". During wartime or when a nation is under attack, sports can also be a powerful weapon Presidents, run campaigns for fuelling the patriotism that binds a nation together. And it can change the course of history. and promote wars." In a key part of his thesis, Matamala describes how a small investment in a struggling baseball team helped propel George W. Bush -then also with a struggling career- to the presidency of the United States. Politics and sports are, in other words, closely entwined, and often very powerfully so. Submitted in partial fulllment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 DANIEL MATAMALA "POWER GAMES: How sports help to elect Presidents, run campaigns and promote wars." Submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 Published by Columbia Global Centers | Latin America (Santiago) Santiago de Chile, August 2014 POWER GAMES: HOW SPORTS HELP TO ELECT PRESIDENTS, RUN CAMPAIGNS AND PROMOTE WARS INDEX INTRODUCTION. PLAYING POLITICS 3 CHAPTER 1. -

Congress and the Baseball Antitrust Exemption Ed Edmonds Notre Dame Law School, [email protected]

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 1994 Over Forty Years in the On-Deck Circle: Congress and the Baseball Antitrust Exemption Ed Edmonds Notre Dame Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Ed Edmonds, Over Forty Years in the On-Deck Circle: Congress and the Baseball Antitrust Exemption, 19 T. Marshall L. Rev. 627 (1993-1994). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/470 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OVER FORTY YEARS IN THE ON-DECK CIRCLE: CONGRESS AND THE BASEBALL ANTITRUST EXEMPTION EDMUND P. EDMONDS* In the history of the legal regulation of professional teams sports, probably the widest known and least precisely understood is the trilogy of United States Supreme Court cases' establishing Major League Baseball's exemption from federal antitrust laws 2 and the actions of the United States Congress regarding the exemption. In the wake of the ouster of Fay Vincent as the Commissioner of Baseball' and against * Director of the Law Library and Professor of Law, Loyola University School of Law, New Orleans. B.A., 1973, University of Notre Dame, M.L.S., 1974, University of Maryland, J.D., 1978, University of Toledo. I wish to thank William P. -

April 7, 2021 Commissioner Rob Manfred Office of the Commissioner of Baseball 1271 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Co

April 7, 2021 Commissioner Rob Manfred Office of the Commissioner of Baseball 1271 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Commissioner Rob Manfred, The Job Creators Network (JCN), a leading small business advocacy organization, is outraged over the recent decision to relocate the Major League Baseball All Star game to Denver. The local government in Georgia—the predesignated location for the event—estimates the exit will amount to a loss of $100 million in tourism spending. For small businesses that have disproportionately suffered through government-imposed pandemic lockdowns over the past year, the financial loss is a punch to the gut and will have an outsized impact on minority-owned businesses. As Sen. Tim Scott points out in a tweet, Atlanta has a majority African American population, while Denver boasts a nine percent make-up. Your decision is punishing the very group you claim to be defending. We demand that you reverse the decision. Giving your organization the benefit of the doubt, the MLB’s choice to relocate the All Star game is based on a misunderstanding of the facts. The recently passed voting rights law in Georgia, which your group has argued applies “restrictions to the ballot box,” is the target of an intense smear campaign perpetuated by activist groups. Regardless of what the legislation actually does, their goal is demonization. The artificial outrage will prove useful when attempting to federalize elections in the form of HR1, legislation that is unconstitutional. Leaders of major American companies and organizations—you among them—have a responsibility to verify the truth, rather than simply echo unfounded accusations. -

Outside the Lines

Outside the Lines Vol. III, No. 3 SABR Business of Baseball Committee Newsletter Summer 1997 Copyright © 1997 Society for American Baseball Research Editor: Doug Pappas, 100 E. Hartsdale Ave., #6EE, Hartsdale, NY 10530-3244, 914-472-7954. E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected]. Chairman’s Letter Thanks to all who attended the Business of Baseball Committee’s annual meeting during the Louisville convention. Some developments from the convention: New Co-Chair. A hearty welcome to Claudia Perry, new Co-Chair of the Business of Baseball Committee. Claudia, who also co-chairs the Women in Baseball Committee, has held numerous SABR offices and is our only four-time Jeopardy champion. In real life she’s a pop music critic at the Newark Star-Ledger. Claudia can be reached at 311 York Street, Jersey City, NJ 07302, or at [email protected]. Proposed Business of Baseball Award. At our annual meeting, Don Coffin proposed that the Committee establish an annual award for excellence in research into the business of baseball. The award -- a cash prize of approximately $200, raised through sponsorship or donations -- would be given annually at the SABR convention. Don and I believe that such an award could raise the Committee’s visibility among academics and other non-SABRites researching in our field, attracting new members and encouraging non- members to send copies of their work to the Committee. Some details of Don’s proposal: • All research published or completed during the previous calendar year would be eligible. • Candidates need not be SABR members, and may be nominated by others or nominate themselves. -

1999-00 NCAA Men's Baseball Championships

Bsball_M (99-00) 11/28/00 8:32 AM Page 14 14 DIVISION I Ba s e b a l l DIVISION I 2000 Championship Hi g h l i g h t s Tigers End Dream Season with Fifth Title: LSU catcher Brad Cresse drilled a single to left field off of Stanford’s Justin Wayne in the bottom of the ninth, plating Ryan Theriot from second base, giving the Tigers a 6-5 win and their fifth College World Series championship since 1991. Cresse was mired in a miserable College World Series before his final at-bat. The senior was 1- for-12 in the CWS prior to his game-winning single. Trey Hodges pitched four scoreless innings for his second win of the tournament. Hodges, who Brad Cresse overcame a slump at the plate to retired 10 of the 11 batters he faced, also picked up a save and was selected as the most out- drive in the title-winning run for LSU June 17. standing player of the College World Series. The catcher’s single to left field scored team - mate Ryan Theriot, giving LSU a 6-5 win over Wayne gave up four hits and four runs in relief of starter Jason Young. Wayne started the fifth St a n f o r d . inning and seven of his first nine outs were strikeouts, four looking. The Tigers’ normally strong offensive game seemed to be silent. But LSU (52-17) tied it in the eighth inning with two home runs, setting up Cresse’s dramatics. -

Best of Lewis County

Best of Lewis County $1 Our Community Selects Its Favorite Local People and Businesses / Inside Chronline.com 2013 Best of Lewis County Midweek Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Edition Thursday, July 25, 2013 Former Museum ‘Enlightened Contact’ Director Group Seeks Contact With Extraterrestrials at Mount Adams Owes $95,895 PROSECUTOR: Under Agreement, Debbie S. Knapp Would Be 116 Before Repaying Stolen Money to Historical Museum By Stephanie Schendel [email protected] The former director of the Lewis County Historical Mu- seum will pay $95,895 in res- titution to the museum, ac- cording to the prosecutor’s of- fice. Debbie S. Knapp has already paid Debbie S. Knapp the museum convicted of theft $20,000, and Amy Nile / [email protected] if she pays the Sophie Sykes, Rainier, Wash., a teacher at Phoenix Rising School in Yelm, meditates Sunday morning inside the vortex, which purportedly is the center of the most minimum restitution payment powerful energy on a UFO ranch near Trout Lake. Sykes traveled with a group organized by the Triad Theater in Yelm. ordered by the judge — $100 a month — she will finish pay- OUTER SPACE TRIP: space adventure, I didn’t know ing the remaining $75,895 in 63 what to expect — or if I believe please see OWES, page Main 16 Reporter Experiences in extraterrestrial contact at all. UFO Ranch With If we did spot a spacecraft, could I report it and still main- Intergalactic Travelers tain a shred of journalistic cred- Woman, TROUT LAKE — Seeing a ibility? And if we encountered spaceship can be part of a spiri- nothing, would I have a story tual journey toward enlighten- to tell? 94, Dies in ment, according to reports from a group of area travelers, who UPON LEARNING THE real-life took a trip to a UFO ranch near story of the woman responsible Chehalis the base of Mount Adams last for the trip, who now refers to weekend. -

1992 Topps Baseball Card Set Checklist

1992 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Nolan Ryan 2 Rickey Henderson RB 3 Jeff Reardon RB 4 Nolan Ryan RB 5 Dave Winfield RB 6 Brien Taylor RC 7 Jim Olander 8 Bryan Hickerson 9 Jon Farrell RC 10 Wade Boggs 11 Jack McDowell 12 Luis Gonzalez 13 Mike Scioscia 14 Wes Chamberlain 15 Dennis Martinez 16 Jeff Montgomery 17 Randy Milligan 18 Greg Cadaret 19 Jamie Quirk 20 Bip Roberts 21 Buck Rodgers MG 22 Bill Wegman 23 Chuck Knoblauch 24 Randy Myers 25 Ron Gant 26 Mike Bielecki 27 Juan Gonzalez 28 Mike Schooler 29 Mickey Tettleton 30 John Kruk 31 Bryn Smith 32 Chris Nabholz 33 Carlos Baerga 34 Jeff Juden 35 Dave Righetti 36 Scott Ruffcorn Draft Pick RC 37 Luis Polonia 38 Tom Candiotti 39 Greg Olson 40 Cal Ripken/Gehrig 41 Craig Lefferts 42 Mike Macfarlane Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Jose Lind 44 Rick Aguilera 45 Gary Carter 46 Steve Farr 47 Rex Hudler 48 Scott Scudder 49 Damon Berryhill 50 Ken Griffey Jr. 51 Tom Runnells MG 52 Juan Bell 53 Tommy Gregg 54 David Wells 55 Rafael Palmeiro 56 Charlie O'Brien 57 Donn Pall 58 Brad Ausmus 59 Mo Vaughn 60 Tony Fernandez 61 Paul O'Neill 62 Gene Nelson 63 Randy Ready 64 Bob Kipper 65 Willie McGee 66 Scott Stahoviak Dft Pick RC 67 Luis Salazar 68 Marvin Freeman 69 Kenny Lofton 70 Gary Gaetti 71 Erik Hanson 72 Eddie Zosky 73 Brian Barnes 74 Scott Leius 75 Bret Saberhagen 76 Mike Gallego 77 Jack Armstrong 78 Ivan Rodriguez 79 Jesse Orosco 80 David Justice 81 Ced Landrum 82 Doug Simons 83 Tommy Greene 84 Leo Gomez 85 Jose DeLeon 86 Steve Finley 87 Bob MacDonald 88 Darrin Jackson 89 Neal -

1994 Topps Baseball Card Set Checklist

1994 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 Mike Piazza 2 Bernie Williams 3 Kevin Rogers 4 Paul Carey 5 Ozzie Guillen 6 Derrick May 7 Jose Mesa 8 Todd Hundley 9 Chris Haney 10 John Olerud 11 Andujar Cedeno 12 John Smiley 13 Phil Plantier 14 Willie Banks 15 Jay Bell 16 Doug Henry 17 Lance Blankenship 18 Greg W. Harris 19 Scott Livingstone 20 Bryan Harvey 21 Wil Cordero 22 Roger Pavlik 23 Mark Lemke 24 Jeff Nelson 25 Todd Zeile 26 Billy Hatcher 27 Joe Magrane 28 Tony Longmire 29 Omar Daal 30 Kirt Manwaring 31 Melido Perez 32 Tim Hulett 33 Jeff Schwarz 34 Nolan Ryan 35 Jose Guzman 36 Felix Fermin 37 Jeff Innis 38 Brent Mayne 39 Huck Flener RC 40 Jeff Bagwell 41 Kevin Wickander 42 Ricky Gutierrez Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 43 Pat Mahomes 44 Jeff King 45 Cal Eldred 46 Craig Paquette 47 Richie Lewis 48 Tony Phillips 49 Armando Reynoso 50 Moises Alou 51 Manuel Lee 52 Otis Nixon 53 Billy Ashley 54 Mark Whiten 55 Jeff Russell 56 Chad Curtis 57 Kevin Stocker 58 Mike Jackson 59 Matt Nokes 60 Chris Bosio 61 Damon Buford 62 Tim Belcher 63 Glenallen Hill 64 Bill Wertz 65 Eddie Murray 66 Tom Gordon 67 Alex Gonzalez 68 Eddie Taubensee 69 Jacob Brumfield 70 Andy Benes 71 Rich Becker 72 Steve Cooke 73 Bill Spiers 74 Scott Brosius 75 Alan Trammell 76 Luis Aquino 77 Jerald Clark 78 Mel Rojas 79 Billy Masse, Stanton Cameron, Tim Clark, Craig McClure 80 Jose Canseco 81 Greg McMichael 82 Brian Turang RC 83 Tom Urbani 84 Garret Anderson 85 Tony Pena 86 Ricky Jordan 87 Jim Gott 88 Pat Kelly 89 Bud Black Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2 90 Robin Ventura 91 Rick Sutcliffe 92 Jose Bautista 93 Bob Ojeda 94 Phil Hiatt 95 Tim Pugh 96 Randy Knorr 97 Todd Jones 98 Ryan Thompson 99 Tim Mauser 100 Kirby Puckett 101 Mark Dewey 102 B.J.