Resale Price Maintenance: Fact and Fancy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Competition Law

COMPETITION LAW SIBERGRAMME 2/2012 ISSN 1606-9986 21 August 2012 Senior Editor ROBERT LEGH Head of the Competition Law Unit of Bowman Gilfillan Inc, Johannesburg This issue by LAUREN RICHARDS and KHOFOLO KRUGER Candidate Attorneys: Bowman Gilfillan Inc Siber Ink Published by Siber Ink CC, B2A Westlake Square, Westlake Drive, Westlake 7945. © Siber Ink CC, Bowman Gilfillan Inc This Sibergramme may not be copied or forwarded without permission from Siber Ink CC Subscriptions: [email protected] or fax (+27) 086-242-3206 To view Competition Tribunal judgments, see: http://www.comptrib.co.za/ Page 2 ISSN 1606-9986 COMPETITION LAW SG 2/2012 IN THIS ISSUE: ESSENTIAL MATTERS: A COMPARATIVE ASSESSMENT OF DIFFERENT APPROACHES TO THE ESSENTIAL FACILITIES DOCTRINE............................. 2 Introduction..............................................................................................................................2 South Africa .............................................................................................................................3 The United States (US).............................................................................................................10 The European Union (EU).......................................................................................................13 Comparison of the US and EU positions .................................................................................15 Conclusion ...............................................................................................................................17 -

The FTC and the Law of Monopolization

George Mason University School of Law Law and Economics Research Papers Series Working Paper No. 00-34 2000 The FTC and the Law of Monopolization Timothy J. Muris As published in Antitrust Law Journal, Vol. 67, No. 3, 2000 This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://papers.ssrn.com/paper.taf?abstract_id=235403 The FTC and the Law of Monopolization by Timothy J. Muris Although Microsoft has attracted much more attention, recent developments at the FTC may have a greater impact on the law of monopolization. From recent pronouncements, the agency appears to believe that in monopolization cases government proof of anticompetitive effect is unnecessary. In one case, the Commission staff argued that defendants should not even be permitted to argue that its conduct lacks an anticompetitive impact. This article argues that the FTC's position is wrong on the law, on policy, and on the facts. Courts have traditionally required full analysis, including consideration of whether the practice in fact has an anticompetitive impact. Even with such analysis, the courts have condemned practices that in retrospect appear not to have been anticompetitive. Given our ignorance about the sources of a firm's success, monopolization cases must necessarily be wide-ranging in their search for whether the conduct at issue in fact created, enhanced, or preserved monopoly power, whether efficiency justifications explain such behavior, and all other relevant issues. THE FTC AND THE LAW OF MONOPOLIZATION Timothy J. Muris* I. INTRODUCTION Most government antitrust cases involve collaborative activity. Collabo- ration between competitors, whether aimed at sti¯ing some aspect of rivalry, such as ®xing prices, or ending competition entirely via merger, is the lifeblood of antitrust. -

Ruling Within Reason: a Reprieve for Resale Price Maintenance

Agenda Advancing economics in business Ruling within reason: a reprieve for resale price maintenance As a result of the US Supreme Court’s recent overturning of the long-standing 1911 Dr Miles decision, which deemed minimum resale price maintenance unlawful per se, this practice is to be judged under the ‘rule of reason’ in the USA, as has been the case with other vertical restraints. Is it therefore time to change the European approach to vertical price fixing? In its June 2007 judgement in Leegin Creative Leather purposes of applying Article 81(1) to demonstrate Products, Inc. v. PSKS, Inc, the US Supreme Court ruled any actual effects on the market.5 that resale price maintenance (RPM) should be judged under the ‘rule of reason’.1 The Leegin ruling overturned In line with the Commission’s approach, in the UK the long-standing 1911 Dr Miles precedent, which held minimum RPM is considered a hard-core practice that that it is per se unlawful under Section 1 of the Sherman ‘almost inevitably’ infringes Article 81 or the Chapter I Act for firms to fix the minimum retail price at which prohibition under the Competition Act 1998.6 Indeed, the retailers may sell goods or services on.2 Office of Fair Trading (OFT) has brought a number of high-profile vertical price fixing cases in recent years, as The outcome of the Leegin case has relieved those who discussed below. support the view that, although under certain circumstances minimum RPM may result in sub-optimal In light of the Leegin judgement, is this the time for market outcomes, this risk is not sufficient to make the European competition policy to move towards an effects- practice illegal per se. -

For Official Use DAF/COMP/WD(2007)100

For Official Use DAF/COMP/WD(2007)100 Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development 04-Oct-2007 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ English text only DIRECTORATE FOR FINANCIAL AND ENTERPRISE AFFAIRS COMPETITION COMMITTEE For Official Use DAF/COMP/WD(2007)100 ROUNDTABLE ON REFUSALS TO DEAL -- Note by the European Commission -- This note is submitted by the Delegation of the European Commission to the Competition Committee FOR DISCUSSION at its forthcoming meeting to be held on 17-18 October 2007. English text only English JT03233260 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format DAF/COMP/WD(2007)100 1. Introduction 1. The starting point for any discussion of the extent to which European competition law may intervene to require a company with market power to supply an input or grant access to its property is to recall the general principle that enterprises should be free to do business – or not to do business – with whomsoever they please, and that they should be free to dispose of their property as they see fit. This general principle derives from the market economy which is the central economic characteristic of the European Union and of each of its Member States, and the principle has been explicitly referred to by the European courts in competition cases1. 2. It is therefore only in the carefully limited circumstances described below that EU law allows this freedom of contract to be over-ridden in the interest of ensuring that competition between enterprises is not unduly restricted to the long-lasting detriment of consumers. -

Use to Effectuate Resale Price Maintenance

Michigan Law Review Volume 56 Issue 3 1958 Regulation of Business - Refusals to Deal - Use to Effectuate Resale Price Maintenance Raymond J. Dittrich, Jr. S.Ed. University of Michigan Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, and the Commercial Law Commons Recommended Citation Raymond J. Dittrich, Jr. S.Ed., Regulation of Business - Refusals to Deal - Use to Effectuate Resale Price Maintenance, 56 MICH. L. REV. 426 (1958). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol56/iss3/6 This Response or Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 426 MICHIGAN LAw REVIEW [ Vol. 56 REGULATION OF BusINEss-REFUSALS To DEAL-UsE To EFFEC TUATE RESALE PRICE MAINTENANCE-A manufacturer,1 acting uni laterally2 and in the absence of either a monopoly position or in tent to monopolize,3 has a generally recognized right to refuse to deal with any person and for any reason he deems sufficient.4 A confusing yet important problem in the field of trade regulation is the extent to which a manufacturer may exercise this right to maintain resale prices by refusing to deal with customers who do not resell at his suggested prices. This difficulty does not arise in the numerous jurisdictions having fair trade laws since these stat utes permit a manufacturer to enter into contracts specifying the minimum or stipulated prices at which his goods are to be resold. -

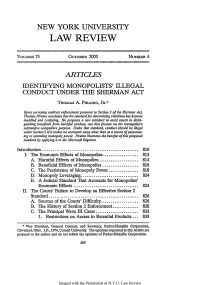

Identifying Monopolists' Illegal Conduct Under the Sherman Act

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 75 OCTOBER 2000 NUMBER 4 ARTICLES IDENTIFYING MONOPOLISTS' ILLEGAL CONDUCT UNDER THE SHERMAN ACT THOMAS A. Pmnn'io, JR.' Upon surveying antitrust enforcement pursuant to Section 2 of the Sherman Act, Thomas Pirainoconcludes that the standardfor determining violations has become muddled and confusing. He proposes a new standard to assist courts in distin- guishing beneficial from harmfid conduc; one that focuses on the monopolist's substantive competitive purpose. Under that standard, conduct should be illegal under Section 2 if it makes no economic sense other than as a means of perpetuat- ing or extending monopoly power. Pirainoillustrates the benefits of this proposed standard by applying it to the Microsoft litigation. Introduction .................................................... 810 I. The Economic Effects of Monopolies ................... 813 A. Harmful Effects of Monopolies ..................... 814 B. Beneficial Effects of Monopolies ................... 816 C. The Persistence of Monopoly Power ................ 818 D. Monopoly Leveraging ............................... 824 E. A Judicial Standard That Accounts for Monopolies' Economic Effects ................................... 824 II. The Courts' Failure to Develop an Effective Section 2 Standard ................................................ 826 A. Sources of the Courts' Difficulty .................... 826 B. The History of Section 2 Enforcement .............. 828 C. The Principal Wave III Cases ....................... 833 1. Restrictions on Access to Essential Products ... 833 * Vice President, General Counsel, and Secretary, Parker-Hannifin Corporation, Cleveland, Ohio. J.D., 1974, Cornell University. The opinions expressed in this Article are personal to the author and do not reflect the opinions of Parker-Hannifin Corporation. 809 Imaged with the Permission of N.Y.U. Law Review NEW YORK UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 75:809 2. Tying and Exclusive Dealing Arrangements ... -

A Comprehensive Economic and Legal Analysis of Tying Arrangements

A Comprehensive Economic and Legal Analysis of Tying Arrangements Guy Sagi* I. INTRODUCTION The law of tying arrangements as it stands does not correspond with modern economic analysis. Therefore, and because tying arrangements are so widely common, the law is expected to change and extensive aca- demic writing is currently attempting to guide its way. In tying arrangements, monopolistic firms coerce consumers to buy additional products or services beyond what they intended to purchase.1 This pressure can be applied because a consumer in a monopolistic mar- ket does not have the alternative to buy the product or service from a competing firm. In the absence of such choice, the monopolistic firm can allegedly force the additional purchase on the consumer at non-beneficial terms. The “tying product” is the one the consumer wants to buy, and the product the firm attaches to the tying product is termed the “tied prod- 2 uct.” * Lecturer, Netanya Academic College; Adjunct Lecturer, The Hebrew University School of Law; LL.B., The Hebrew University School of Law; LL.M. and J.S.D. Columbia University School of Law. 1. In a competitive market, consumers can choose to buy from firms that do not tie products, as opposed to ones that do. The tying firm, in such a case, would then lose out. At the same time, it is possible that in a competitive market, some products would still be offered together because it would be beneficial to both producers and consumers. 2. It can sometimes be difficult to differentiate between the tying of two separate products and the sale of two components forming a single whole product. -

Resale Price Maintenance and Minimum

Presenting a live 90-minute webinar with interactive Q&A Resale Price Maintenance and Minimum Advertised Pricing: Structuring to Minimize Antitrust Scrutiny State, Federal, and International Treatment of RPM Agreements and MAP Policies THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2019 1pm Eastern | 12pm Central | 11am Mountain | 10am Pacific Today’s faculty features: Michael A. Lindsay, Partner, Dorsey & Whitney LLP, Minneapolis William L. Monts, III, Partner, Hogan Lovells US, Washington, D.C. The audio portion of the conference may be accessed via the telephone or by using your computer's speakers. Please refer to the instructions emailed to registrants for additional information. If you have any questions, please contact Customer Service at 1-800-926-7926 ext. 1. Tips for Optimal Quality FOR LIVE EVENT ONLY Sound Quality If you are listening via your computer speakers, please note that the quality of your sound will vary depending on the speed and quality of your internet connection. If the sound quality is not satisfactory, you may listen via the phone: dial 1-866-961-8499 and enter your PIN when prompted. Otherwise, please send us a chat or e-mail [email protected] immediately so we can address the problem. If you dialed in and have any difficulties during the call, press *0 for assistance. Viewing Quality To maximize your screen, press the F11 key on your keyboard. To exit full screen, press the F11 key again. Continuing Education Credits FOR LIVE EVENT ONLY In order for us to process your continuing education credit, you must confirm your participation in this webinar by completing and submitting the Attendance Affirmation/Evaluation after the webinar. -

A Proposal to Enhance Antitrust Protection Against Labor Market Monopsony Roosevelt Institute Working Paper

A Proposal to Enhance Antitrust Protection Against Labor Market Monopsony Roosevelt Institute Working Paper Ioana Marinescu, University of Pennsylvania Eric A. Posner, University of Chicago1 December 21, 2018 1 We thank Daniel Small, Marshall Steinbaum, David Steinberg, and Nancy Walker and her staff, for helpful comments. 1 The United States has a labor monopsony problem. A labor monopsony exists when lack of competition in the labor market enables employers to suppress the wages of their workers. Labor monopsony harms the economy: the low wages force workers out of the workforce, suppressing economic growth. Labor monopsony harms workers, whose wages and employment opportunities are reduced. Because monopsonists can artificially restrict labor mobility, monopsony can block entry into markets, and harm companies who need to hire workers. The labor monopsony problem urgently calls for a solution. Legal tools are already in place to help combat monopsony. The antitrust laws prohibit employers from colluding to suppress wages, and from deliberately creating monopsonies through mergers and other anticompetitive actions.2 In recent years, the Federal Trade Commission and the Justice Department have awoken from their Rip Van Winkle labor- monopsony slumber, and brought antitrust cases against employers and issued guidance and warnings.3 But the antitrust laws have rarely been used by private litigants because of certain practical and doctrinal weaknesses. And when they have been used—whether by private litigants or by the government—they have been used against only the most obvious forms of anticompetitive conduct, like no-poaching agreements. There has been virtually no enforcement against abuses of monopsony power more generally. -

Buyer Power: Is Monopsony the New Monopoly?

COVER STORIES Antitrust , Vol. 33, No. 2, Spring 2019. © 2019 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association. Buyer Power: Is Monopsony the New Monopoly? BY DEBBIE FEINSTEIN AND ALBERT TENG OR A NUMBER OF YEARS, exists—or only when it can also be shown to harm consumer commentators have debated whether the United welfare; (2) historical case law on monopsony; (3) recent States has a monopoly problem. But as part of the cases involving monopsony issues; and (4) counseling con - recent conversation over the direction of antitrust siderations for monopsony issues. It remains to be seen law and the continued appropriateness of the con - whether we will see significantly increased enforcement Fsumer welfare standard, the debate has turned to whether the against buyer-side agreements and mergers that affect buyer antitrust agencies are paying enough attention to monopsony power and whether such enforcement will be successful, but issues. 1 A concept that appears more in textbooks than in case what is clear is that the antitrust enforcement agencies will be law has suddenly become mainstream and practitioners exploring the depth and reach of these theories and clients should be aware of developments when they counsel clients must be prepared for investigations and enforcement actions on issues involving supply-side concerns. implicating these issues. This topic is not going anywhere any time soon. -

Resale Price Maintenance After Monsanto: a Doctrine Still at War with Itself*

RESALE PRICE MAINTENANCE AFTER MONSANTO: A DOCTRINE STILL AT WAR WITH ITSELF* TERRY CALVANI** AND ANDREW G. BERG*** In this article, two enforcement officials at the Federal Trade Com- mission reexamine resale price maintenance in light of the Supreme Court's recent decision in Monsanto Co. v. Spray-Rite Service Corp. Commissioner Calvani and Mr. Berg consider both antitrust law and economic policy in their review of the history of resale price mainte- nance; they point out the chronic inconsistencies to which this antitrust regime has been subject, and identify these same inconsistenciesat work in Monsanto. The authorsset forth three theses with respect to Mon- santo: first, that the Court intimated a willingness to reconsiderat some future time the per se standardof illegalityfor resale price maintenance; second, that the Court recognized the continuing vitality of the Colgate doctrine, which had been seriously questionedin recent years; and, third, that the Monsanto Court unsuccessfully attempted to delineate a work- able evidentiary standard applicable to communications between sellers and resellers when it is alleged that such communications constitute an illegal contract, combination, or consiracy under section one of the Sherman Act. The authorssuggest that, taken together, these elements in Monsanto display a doctrine at war with itself The authorsconclude by examining the possible implications of the Monsanto decisionfor the future direction of the law of resale price maintenance. Typically, antitrust issues do not generate widespread public inter- est; there is, however, a considerable amount of such interest in resale price maintenance,' as evidenced by numerous articles on the subject in newspapers and periodicals of general circulation.2 This high level of © 1984 Terry Calvani & Andrew G. -

Resale Price Maintenance: Economic Theories and Empirical Evidence

"RESALE PRICE MAINTENANCE: ECONOMIC THEORIES AND EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE Thomas R. Overstreet, Jr. Bureau of Economics Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commission November 1983 RESALF. PRICE INTF.NANCE: ECONO IC THEORIES AND PIRICAL EVIDENCE Thomas R. Overstreet, Jr. Bureau of Economics Staff Report to the Federal Trade Commiss ion November 1983 . FEDERAL TRDE COM~ISSION -f. JAMES C. ~ILLER, III, Chairman MICHAEL PERTSCHUK, Commissioner PATRICIA P. BAILEY, Commissioner GEORGE W. DOUGLAS, Commissioner TERRY CALVANI, Commi S5 ioner BUREAU OF ECONO~ICS WENDY GRA~, Director RONALD S. BOND, Deputy Director for Operations and Research RICHARD HIGGINS, Deputy Director for Consumer Protection and Regulatory Analysis JOHN L. PETE , Associate Director for Special Projects DAVID T. SCHEFF N, Deputy Director for Competition and Anti trust PAUL PAUTLER, Assistant to Deputy Director for Competition and Antitrust JOHN E. CALFEE, Special Assistant to the Director JAMES A. HURDLE, Special Assistant to . the Director THOMAS WALTON, Special Assistant to the Director KEITH B. ANDERSON, Assistant Director of Regulatory Analysis JAMES M. FERGUSON, Assistant Director for Antitrust PAULINE IPPOLITO, Assistant Director for Industry Analysis WILLIAM F. LONG, ~anager for Line of Business PHILIP NELSON, Assistant Director for Competition Analysis PAUL H. RUBIN, Assistant Director for Consumer Protection This report has been prepared by an individual member of the professional staff of the FTC Bureau of Economics. It rsfle cts solely the views of the author, and is not intended to represent the position of the Federal Trade Commission, or necessarily the views of any individual Commissioner. -ii - fI. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank former FTC Commissioner David A.