The Discoveries at Fassy House at Larchant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arrêté Préfectoral N° 2015/DDT/SEPR/137 Définissant

PREFET DE SEINE-ET-MARNE Direction départementale des territoires Service environnement et prévention des risques Arrêté préfectoral n° 2015/DDT/SEPR/137 définissant les seuils entraînant des mesures de limitation provisoire des usages de l'eau et de surveillance sur les rivières et les aquifères de Seine-et-Marne Le Préfet de Seine-et-Marne Officier de la Légion d’honneur, Chevalier de l’Ordre national du Mérite, VU le code de l’environnement et notamment ses articles L.210-1, L.211-3, L.214-7, L.214-18, L.215-10 R.211-66 à R.211-70, R212-1 à 2, R.213-14 à R.213-16 et R.216-9 ; VU le code de la santé publique ; VU le décret du Président de la République en date du 31 juillet 2014 portant nomination de Monsieur Jean-Luc MARX, préfet de Seine-et-Marne (hors classe); VU l’arrêté du Premier Ministre en date du 14 juin 2013 nommant Monsieur Yves SCHENFEIGEL, directeur départemental des territoires de Seine-et-Marne ; VU l’arrêté préfectoral n°14/PCAD/92 du 01 septembre 2014 donnant délégation de signatures à Monsieur Yves SCHENFEIGEL, administrateur civil hors classe, directeur départemental des territoires de Seine-et-Marne ; VU le décret n° 2004-374 du 29 avril 2004, relatif aux pouvoirs des préfets, à l'organisation et à l’action des services de l’État dans les régions et départements ; VU l’arrêté n°2009-1531 du 20 novembre 2009 approuvant le Schéma Directeur d’Aménagement et de Gestion des Eaux du Bassin Seine-Normandie ; VU l’arrêté n°2015 103-0014 du 13 avril 2015 du Préfet de la région Île-de-France, Préfet de Paris, Préfet coordonnateur du bassin Seine-Normandie, préconisant des mesures coordonnées de gestion de l’eau sur le réseau hydrographique du bassin Seine-Normandie en période de sécheresse et définissant des seuils sur certaines rivières du bassin entraînant des mesures coordonnées de limitation provisoire des usages de l’eau et de surveillance sur ces rivières et leur nappe d’accompagnement. -

Président Du Département De Seine-Et-Marne

SEINE&MARNEMAG Le magazine de votre département • seine-et-marne.fr fl N°118 - MAI/JUIN 2018 JEAN-LOUIS THIÉRIOT « VALORISER LES ATOUTS EXTRAORDINAIRES DE LA SEINE-ET-MARNE » SOMMAIRE RETOUR DANS VOTRE P. 4 EN IMAGES P.15 DOSSIER P.24 CANTON Élection du Président Jean-Louis Thiériot : un exécutif qui s’inscrit dans la continuité P.10 ACTUALITÉS P. 26AGENDA 10. La limitation à 80 km/h sur les routes secondaires fait débat VOUS 11. Le Département s’engage P. AVEZ AIMÉ… pour la réussite des collégiens 32 GRAND P.12 ANGLE Politiques contractuelles et contrats ruraux : des leviers pour le développement local P.14 DÉCOUVERTE P.20 INNOVER Le patrimoine à l’honneur 20. Quartz Alliance, P. TRIBUNES la technique sur mesure 33 21. Entreprises : candidatez à un marché public en quelques clics ! LES ÉLUS DE P. 34 VOTRE CANTON Pour joindre le Département, P.22 PORTRAIT un seul numéro : 01 64 14 77 77 PROCHAINE PARUTION : JUILLET 2018 22. Julien Labbé, un chef cuisinier d’EHPAD au top ! RETROUVEZ LE MAGAZINE DÉPARTEMENTAL EN LIGNE AINSI QUE L’E-MAG 23. Morgan Ciprès : « On s’est SUR SEINE-ET-MARNE.FR battus comme des lions » Département de Seine-et-Marne – Direction de la communication – Hôtel du Département – CS 50377 – 77010 Melun Cedex – 01 64 14 77 77 – Diffusion 01 64 14 70 48 – [email protected] – Directeur de la Publication : Jean-Louis Thiérot – Rédacteur en chef : Direction de la communication – Rédaction : Laura Sarfati, Nathalie Rouveyre-Scalbert (p.22) – Conception de la maquette et mise en pages : Direction de la communication et , 10204-MEP – Photos : Patrick Loison, Getty Images – Impression : Siep – Distribution : Adrexo – 01 64 10 02 85 – Tirage : 579 300 exemplaires – Versions braille et sonore disponibles sur simple demande auprès de l’association Donne-moi tes yeux – 01 47 05 40 30. -

Nemours - FRANCE E R D 0 E 0 0 0 0 N 0

E " 0 ' 3 3 ° 2 2°36'0"E 2°39'0"E 2°42'0"E 2°45'0"E N " 0 N ' " 1 0 ' 2 ° 1 8 2 ° 4 8 4 470000 475000 480000 E L Activation ID: EMS N-028 IL V P roduct N.:11-NEMO UR S , v1, English N O P M 'A R D T Nemours - FRANCE E R D 0 E 0 0 0 0 N 0 0 O 0 5 Montcourt-Fromonville N 5 3 3 Flood - June 2016 V 5 5 N IL " L 0 ' E N " 8 0 Impact assessment on population ' 1 ° 8 8 1 4 ° - Detail - 8 4 P roduction date: 07/09/2016 AIS NE P aris ^ English Channel S eine-et-Marne P aris Y velines 01 ^ Ile-de- Marne France France 02 03 S e Bay of Biscay in e S Essonne eine 04 05 06 Mediterranean Fontaineblleau Sea Larchant 07 08 09 Y L o n o n i Aube n e 10 11 g 12 13 14 Y onne Loiret Montargis Bourgogne- Centre-Val 15 16 Franche-Comté L 0 20 oire de Loire k m Cartographic Information Full color A1, high resolution (100dpi) R 1:25 000 DE LA RCH ANT 0 1 2 K m Darvault Grid: W GS 1984 Z one 31 N map coordinate system ± Nemours Tick mark s: W GS 84 geographical coordinate system Legend Saint-Pierre-lès-Nemours General Information Transportation Land Use r Area of Interest Continuous urban fabric ! Aerodrom e masque_ max_ flood_ extent_ utm 31n Discontinuous urban fabric Quercheville Administrative boundaries "£ Bridge Industrial or commercial units R egion R oad and rail netw ork s and associated land | Harbour P rovince n P ort areas 0 0 Settlements u Helipad Airports 0 0 !( 0 0 5 5 ! P opulated P lace Mineral extraction sites 4 4 Heliport 3 3 u ") Green urban areas 5 5 R ailw ay S port and leisure facilities Motorw ay Non-irrigated arable land RT E DE P rim -

Le Bulletin N°58 – MARS 2019

Le Lyricantois Bulletin d’informations municipales n° 58 - mars 2019 Le mot du maire in décembre 2018 nous avons eu l’occasion de terminer la procé- dure du passage du POS en PLU. Désormais nous pouvons envi- F sager concrètement pour les années à venir le paysage de notre village. Ce travail fastidieux a demandé beaucoup de temps, beaucoup de travail. Je remercie au passage les élus qui s’y sont consacrés sans compter, durant plusieurs années, et tout particulièrement nos secré- taires pour leur volonté de bien faire et leur rigueur dans le suivi de ce fastidieux dossier. Je remercie aussi les habitants qui ont compris que nous étions là pour défendre leurs intérêts tout en ayant à cœur de res- pecter l’attrait et le futur du village. Larchant n’est pas un village seul au monde et il doit préparer son avenir dans le respect de règles géné- rales imposées à toutes les communes de France, dans un schéma de cohérence territoriale. L’année 2018 sera aussi marquée pour les 60 années à venir par la fina- lisation de la construction de notre nouvelle station d’épuration. Le chantier s’est très bien déroulé. Il faut dire que le temps a été de la par- tie. Comme promis il y a quatre ans, bien que nous ayons été abandon- nés injustement en cours de route par un de nos financeurs institution- nels, cette nouvelle station n’entraîne pas d’augmentation du prix de l’eau et de l’assainissement. Nous ne pouvons que nous en féliciter. C’était un pari, il est gagné ! Vous avez pu voir en 2018 un chantier d’arasement des bas-côtés sur la route de la Dame Jouanne et du Moulin à Vent. -

Nemours - FRANCE R E 0 D 0 0 E 0 0 Montcourt-Fromonville! 0

E " 0 ' 3 3 ° 2 2°36'0"E 2°39'0"E 2°42'0"E 2°45'0"E N " 0 N ' " 1 0 ' 2 ° 1 8 2 ° 4 8 4 470000 475000 480000 n| E L Activation ID: EMSN-028 IL V P roduct N.:11-NEMO U RS, v1, English N O P M 'A R D T Nemours - FRANCE R E 0 D 0 0 E 0 0 Montcourt-Fromonville! 0 0 N 0 5 5 Flood - June 2016 O 3 N 3 5 5 N V " IL 0 N ' L Observed flood extent - Detail " 8 E 0 ' 1 ° 8 8 1 ° 4 P roduction date: 07/09/2016 8 4 AISNE P aris ^ English Channel Seine-et-Marne P aris Yvelines 01 ^ 69 Ile-de- Marne # France France 02 03 S e Bay of Biscay in e S Essonne eine 04 05 06 Mediterranean Fontaineblleau Sea 07 08 09 Y L o n o n i Aube n e !Larchant 10 11 g 12 13 14 Yonne Loiret Montargis Bourgogne- Centre-Val 15 16 Franche-Comté L 0 20 oire de Loire km Cartographic Information Full color A1, high resolution (200dpi) 100 1:25 000 0 1 2 R D E L Km ARC HAN SEINE-ET-MARNE T ! n| Darvault Grid: W GS 1984 Zone 31 N map coordinate system ± T ick marks: W GS 84 geographical coordinate system 0 10 0 Legend 0 1 Nem!ours ! Crisis Information Settlements Transportation 74 r # Flooded Area ! P opulated P lace Saint-Pierre-lès-Nemours (from 31/05 to 09/06/2016) ! Aerodrome Buildings £ General Information " Bridge K Industry / Utilities Quercheville Area of Interest ! | H arbour Q uarry n Administrative boundaries P ower Station (!u H elipad Region 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 Physiography ")u H eliport 5 5 P rovince 4 4 3 3 # Spot elevation point (m) 5 5 Railway Point of Interest 0 0 Contour lines and Motorway 1 elevation (10m spacing) # RT 9 Institutional E 77 DE P rimary Road 1 S Hydrology 0 E 0 N 0 0 S Secondary Road 1 Medical K River; Stream N " Local Road 0 N ' " 5 0 ' 1 ° 5 8 R 1 ° 4 8 D Map Information 4 E B From the 31st of May to early J une 2016, ex ceptional flooding occured after several days of A G A heavy rain in France. -

Recensement De La Population

Recensement de la population Populations légales en vigueur à compter du 1er janvier 2009 Arrondissements - cantons - communes 77 SEINE-ET-MARNE Recensement de la population Populations légales en vigueur à compter du 1er janvier 2009 Arrondissements - cantons - communes 77 - SEINE-ET-MARNE RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE SOMMAIRE Ministère de l’économie, de l’industrie et de l’emploi Institut national de la statistique et des études Introduction.....................................................................................................77-V économiques 18, boulevard Adolphe Pinard 75675 Paris cedex 14 Tableau 1 - Population des arrondissements et des cantons........................ 77-1 Tél. : 01 41 17 50 50 Directeur de la publication Tableau 2 - Population des communes..........................................................77-3 Jean-Philippe Cotis INSEE - février 2009 INTRODUCTION 1. Liste des tableaux figurant dans ce fascicule Tableau 1 - Populations des arrondissements et des cantons Tableau 2 - Populations des communes, classées par ordre alphabétique 2. Définition des catégories de la population1 Le décret n° 2003-485 du 5 juin 2003 fixe les catégories de population et leur composition. La population municipale comprend les personnes ayant leur résidence habituelle sur le territoire de la commune, dans un logement ou une communauté, les personnes détenues dans les établissements pénitentiaires de la commune, les personnes sans abri recensées sur le territoire de la commune et les personnes résidant habituellement dans une habitation -

Mise En Page 1 28/06/2019 11:14 Page2 Horaire Ligne 34 - 2018.Qxp Mise En Page 1 14/09/2018 10:24 Page2

Horaire Ligne 34.qxp_Mise en page 1 28/06/2019 11:14 Page2 Horaire Ligne 34 - 2018.qxp_Mise en page 1 14/09/2018 10:24 Page2 Itiné rai res, ho rai res et in fo t rafic : Expr ess 34 CHATEAU-LANDON MEL UN 3 prépa rez tous vos dépla ceme nts avec PROVINS PROVINS 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 l’application d’Île-de-France Mobilités L U N D I à V E N D R E D I Période de fonctionnement A A A A A A A1 A SC A A A A SC A A A1 A A1 A A1 A1 A A A1 A A A A SC A A A A A A A1 A SC A A1 A A1 A SC A A1 A A A1 A A1 A A A A A A A VACANCESVACANCES SCOLAIRESSCOLAIRES 2019-20202019-2020 LUNDI à VENDREDI Période de fonctionnement A A A A A A A A SC A A A A SC A A A A A A A A A A A A A A A SC A A A A A A A A SC A A A A A SC A A A A A A A A A A A A A A LUNDI à VENDREDI P ériode Jours dede fonctionnementfonctionnement LAàV L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV LAàV1 L AàV LSCàV L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV LSCàV L AàV L AàV LAàV1 L AàV LAàV1 L AàV LAàV1 L AàV1 L AàV L AàV LAàV1 L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV MSCe L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV LAàV1 L AàV L M SC_J V L AàV LAàV1 L AàV LAàV1 L AàV L M SC_J V L AàV LAàV1 L AàV L AàV LAàV1 L AàV LAàV1 L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV L AàV VacancesVacVaACANCESnces dede lala ToussaintTSCOLAIRESoussaint 2018-2019 Jours de fonctionnement LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV Me LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LM_JV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LM_JV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV LàV Du Samedi 19 Octobre 2019 au Dimanche 3 Novembre 2019 EGREVILLE -

À Vos Idées Pour La 2E Journée Citoyenne ! Festival « Emmenez-Moi... » Pour Valoriser Le Patrimoine Myrtille Sort Son Deuxi

MENSUEL 39 JUIN 2021 c’est vous Le Pnouveau 4-5 । Lumière sur site internet est en ligne ! P 3 । Actions locales P6 । Action citoyenne P7 । Ressources locales Festival « Emmenez-moi... » À vos idées pour la Myrtille sort son pour valoriser le patrimoine 2e journée citoyenne ! deuxième album ÉDITO Vie quotidienne 02 Rappel des règles de bon Chères Thomeryonnes, chers Thomeryons, voisinage Avec l’arrivée des beaux jours, les travaux de Le mois de juin débute sur les chapeaux de roues. jardinage et de bricolage reprennent... mais attention Tout d’abord, la vaccination se poursuit et s’ouvre au bruit ! Afin de préserver la bonne entente et la dès le 15 juin aux jeunes de 12 à 18 ans, 350 créneaux tranquillité de tous, les travaux occasionnant des leur seront donc dédiés les 16 et 17 juin. Le retour nuisances sonores ne sont autorisés, par arrêté à une vie, que nous souhaitons la plus normale préfectoral, que sur certaines plages horaires : possible pour tous, passe aussi par la vaccination • de 8h à 12h et de 14h à 20h du lundi au vendredi de nos ados, « je les protège, je les vaccine ». • de 9h à 12h et de 14h à 19h le samedi • de 10h à 12h les dimanches et jours fériés. Le mois de juin, c’est aussi le mois des élections Merci de les respecter ! départementales et régionales. Elles retiendront les équipes qui mèneront des politiques aussi importantes que celles des solidarités pour Covid-19 le Département ou celles du développement La vaccination économique pour la Région. Elles mettront en ouverte dès l’âge de 12 ans place les politiques contractuelles qui définiront les règles d’affectation des subventions qui viendront Comme cofinancer nos projets. -

FONTAINEBLEAU – CHEMIN DE FER DES CARRIERES DE LONG-ROCHER IRSP N°77186.1 Inventaire Des Réseaux Spéciaux Et Particuliers

FONTAINEBLEAU – CHEMIN DE FER DES CARRIERES DE LONG-ROCHER IRSP n°77186.1 Inventaire des Réseaux Spéciaux et Particuliers Chemin de fer des carrières de grès du Long-Rocher au canal du Loing Chemin de fer des carrières des Brosses Code INSEE – Commune(s) 77170 – Episy 77186 – Fontainebleau 77312 – Montigny-sur-Loing Seine-et-Marne N°RSU N° officiel Intitulé Ouverture Fermeture FONTAINEBLEAU - Long Rocher Carrières > EPISY - 77186.01M / 1841 ≤ 1869 Canal du Loing Embarcadère MONTIGNY SUR LOING - Les Brosses Carrière > 77312.01M / ≥ 1900 ≤ 1950 MONTIGNY SUR LOING - Route de Larchant 1800 1825 1850 1875 1900 1925 1950 1975 2000 2025 Code des chemins de fer – 1ère partie - 1845 Books.google.fr Archives parlementaires de 1787 à 1860 – 2ème série – Tome LXXVI Books.google.fr Code des ponts et chaussées et des mines – Tome IV - 1847 Gallica.bnf.fr CARRIÈRES ET CARRIERS DE GRÈS DU MASSIF DE FONTAINEBLEAU ET ALENTOURS Wordpress.com Etude documentaire exploitation grès Fontainebleau www1.onf.fr Histoire Montigny-sur-Loing Montignysurloing.fr [email protected] ATTENTION : le fonctionnement des liens vers les sites mentionnés n’est pas garanti. L’accès à certains sites est dangereux et/ou situés sur des propriétés privées. Ne cherchez pas à pénétrer par effraction. Essayez d’obtenir l’autorisation de pénétrer et circuler, si c’est possible. Laissez les lieux en l’état. N’abîmez pas les clôtures et les cultures. Refermez les barrières trouvées fermées. Ne touchez pas aux barrières trouvées ouvertes. 1 IRSP – 29 novembre 2020 FONTAINEBLEAU – CHEMIN DE FER DES CARRIERES DE LONG-ROCHER IRSP n°77186.1 Inventaire des Réseaux Spéciaux et Particuliers Long-Rocher FONTAINEBLEAU Les brosses 77312.01M 77186.01M Sorques MONTIGNY/LOING La Gravine Embarcadère LA GENEVRAYE Episy MORET-LOING-ET-ORVANNE Ecartement Etroit abandonné Les extrémités de la ligne ne sont pas connues avec précision. -

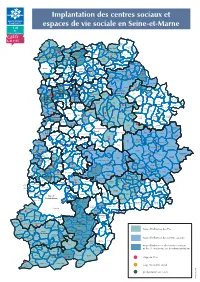

Carte Evs Et Cs 01 2018

ImplantationImplantation des centres des sociaux centres en sociaux Seine-et-Marne et espaces de vie sociale en Seine-et-Marne Crouy Othis Vinci sur Manœuvre Moussy- St Ourcq Oissery le-Neuf Pathus Puisieux Coulombs Rouvres Douy la Ramée May en Multien en Valois Dammartin- Le Germigny Long- en-Goële Forfry Plessis sous Moussy- perrier Marchémoret le-Vieux Trocy Placy Coulombs Gesvres en Pays de l’Ourcq Mauregard Villeneuve- le Etrépilly Lizy sur Ourcq St Mard St Soupplets Marcilly Multien Vendrest sous-Dammartin Montgé- Chapitre Dhuisy Roissy Pays de France en-Goële Juilly Cuisy Barcy Congis Mary sur Ocquerre Le Mesnil-Amelot Thieux sur Marne Cocherel Le Monthyon Vinantes Le Plessis- Therouanne Plessis- Varreddes Isles Nantouillet l'Evêque Chambry aux-Bois les Meldeuses Ste Aulde Iverny Penchard Tancrou Compans Plaines et St Mesmes Crégy Germigny Villeroy Armentières en Brie Jaignes Mitry-Mory Monts de France Chauconin les Poincy Evêque Chamigny Nanteuil Luzancy Chamy Neufmontiers Meaux sur Gressy Meaux Marne Messy Pays de Meaux Changis sur Marne Ussy sur Marne Méry Trilport sur Citry Charmentray Trilbardou 4 Marne Villenoy Reuil en Brie Fresnes- Villeparisis Claye-Souilly Montceaux Saint Jean La Ferté sur- Fublaines les Meaux Sammeron sous Vignely les deux Sept Saâcy sur Marne Marne Precy- Nanteuil Mareuil jumeaux Sorts Jouarre sur- les les St Annet- Marne Meaux Meaux Fiacre Signy Signets Courtry Le Pin Isles Villemareuil Villevaudé sur-Marne Lesches les Villenoy Boutigny Jablines Bussières Bassevelle St Carnetin Quincy Vaucourtois St -

Circonscriptions 2019 Avec REP Et

Crouy- sur-Ourcq V Othis Manœuvrincy- Coulombs- en-Valois Ger Coulombs St- e sous- Moussy- Oissery Puisieux Le Plessis-May-en-Multien mign le-Neuf Pathus Douy- DAMMARTIN- Rouvres la-Ramée Plac RPI n°28 y- EN-GOËLE Marchémoret Forfry RPI n°68 Trocy- y Moussy- Longperrier en- e Vendrest Dhuisy le-Vieux es- Marcilly Multien Dammartin-Montgé- pitr RPI n°35 Lizy-sur-Ourcq d Villeneuve- d St-Soupplets RPI n°85 Etrépilly Gesvr gar sous- Juilly en-Goële le-Cha Ocquerre e Dammartin St-Mar RPI n°32 Cuisy Monthyon Barcy Congis-sur- Mary- Cocherel Maur Le Mesnil- en-Goële sur-Marne V Varreddes Thérouanne RPI n°27 Thieux inantes Le Le Plessis- RPI n°8 Amelot Plessis- l'Evêque Ste-Aulde Nantouillet aux- Tancrou Bois Iver Meaux Nord Isles-les- ny RPI n°50 Penc Chambry Meldeuses y har ne Nanteuil- Compans d Jaignes sur RPI n°69 V y- Germigny- Chamigny iller es-en-Brie -Mar St-Mesmes Chauconin- l'Evêque -Mar Mitry-Mory Crég mentièr Luzanc o Neufmontiers Ar Gr y Poincy Ussy- lès-M.MEAUX LA ne Changis- y-sur Citr essy Charny sur-Marne Messy Reuil- RPI n° 43 y 7 / 16 sur-Marne FERTÉ- a Trilport y en-Brie Mér Meaux Montceaux- SOUS- St-Jean- RPI n°42 Saâcy- RPI n°23 mentr Fresnes- Villenoy lès-Meaux les-deux- Se pt- JOUARRE sur-Marne Villeparisis CLAYE-SOUILLY sur-Marne dou Villenoy Sammeron Sorts Char Fublaines Jumeaux Précy- Trilbar y RPI n°9 sur-Marne Nanteuil- Jouarre Claye-Souilly Vignel euil- Signy-Signets Bussières Bassevelle Cour lès-Meaux St- Annet- Isles-lès- Mar RPI n°93 sur-Marne hes Fiacre Villemareuil tr Le Pin Jablines Villenoy lès-Meaux La Ferté- y RPI n°62 St-Cyr- Car RPI n°76 Lesc Esb RPI n°49 Villevaudé netin Boutigny sur-Morin -Morin Orly- ly Condé-Ste- St-Ouen- Boitron Hondevilliers t Libiaire Quincy- La Haute-MaisonPierre-Levée sous- sur sur-Morin Brou- Thorigny- CoulommesVaucourtois RPI n°15 y a Couill Voisins RPI n°29 RPI n°47 sur- sur-M. -

Recensement De La Population

Recensement de la population Populations légales en vigueur à compter du 1er janvier 2019 Arrondissements - cantons - communes 77 SEINE-ET-MARNE INSEE - décembre 2018 Recensement de la population Populations légales en vigueur à compter du 1er janvier 2019 Arrondissements - cantons - communes 77 - SEINE-ET-MARNE RÉPUBLIQUE FRANÇAISE SOMMAIRE Ministère de l'Économie et des Finances Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques Introduction..................................................................................................... 77-V 18, boulevard Adolphe Pinard 75675 Paris cedex 14 Tableau 1 - Population des arrondissements ................................................ 77-1 Tél. : 01 41 17 50 50 Directeur de la Tableau 2 - Population des cantons et métropoles ....................................... 77-2 publication Jean-Luc Tavernier Tableau 3 - Population des communes.......................................................... 77-3 INSEE - décembre 2018 INTRODUCTION 1. Liste des tableaux figurant dans ce fascicule Tableau 1 - Population des arrondissements Tableau 2 - Population des cantons et métropoles Tableau 3 - Population des communes, classées par ordre alphabétique 2. Définition des catégories de la population1 Le décret n° 2003-485 du 5 juin 2003 fixe les catégories de population et leur composition. La population municipale comprend les personnes ayant leur résidence habituelle sur le territoire de la commune, dans un logement ou une communauté, les personnes détenues dans les établissements pénitentiaires