The Gendering of Helen Frankenthaler's Mountains and Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dlkj;Fdslk ;Lkfdj

MoMA PRESENTS SCREENINGS OF VIDEO ART AND INTERVIEWS WITH WOMEN ARTISTS FROM THE ARCHIVE OF THE VIDEO DATA BANK Video Art Works by Laurie Anderson, Miranda July, and Yvonne Rainer and Interviews With Artists Such As Louise Bourgeois and Lee Krasner Are Presented FEEDBACK: THE VIDEO DATA BANK, VIDEO ART, AND ARTIST INTERVIEWS January 25–31, 2007 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters NEW YORK, January 9, 2007— The Museum of Modern Art presents Feedback: The Video Data Bank, Video Art, and Artist Interviews, an exhibition of video art and interviews with female visual and moving-image artists drawn from the Chicago-based Video Data Bank (VDB). The exhibition is presented January 25–31, 2007, in The Roy and Niuta Titus Theaters, on the occasion of the publication of Feedback, The Video Data Bank Catalog of Video Art and Artist Interviews and the presentation of MoMA’s The Feminist Future symposium (January 26 and 27, 2007). Eleven programs of short and longer-form works are included, including interviews with artists such as Lee Krasner and Louise Bourgeois, as well as with critics, academics, and other commentators. The exhibition is organized by Sally Berger, Assistant Curator, Department of Film, The Museum of Modern Art, with Blithe Riley, Editor and Project Coordinator, On Art and Artists collection, Video Data Bank. The Video Data Bank was established in 1976 at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago as a collection of student productions and interviews with visiting artists. During the same period in the mid-1970s, VDB codirectors Lyn Blumenthal and Kate Horsfield began conducting their own interviews with women artists who they felt were underrepresented critically in the art world. -

Gallery-Guide-Off-Kilter For-Web.Pdf

Dave Yust, Circular Composition (#11 Round), 1969 UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR THE ARTS 1400 Remington Street, Fort Collins, CO artmuseum.colostate.edu [email protected] | (970) 491-1989 TUES - SAT | 10 A.M.- 6 P.M. THURSDAY OPEN UNTIL 7:30 P.M. ALWAYS FREE OFF KILTER, ON POINT ART OF THE 1960s FROM THE PERMANENT COLLECTION ABOUT THE COLLECTION Drawing on the museum’s longstanding strength in 20th-century art of the United States and Europe and including long-time visitor favorites and recent acquisitions, Off Kilter, On Point: Art of the 1960s from the Permanent Collection highlights the depth and breadth of artworks in the museum permanent collection. The exhibition showcases a wide range of media and styles, from abstraction to pop, presenting novel juxtapositions that reflect the tumult and innovations of their time. The 1960s marked a time of undeniable turbulence and strife, but also a period of remarkable cultural and societal change. The decade saw the civil rights movement and the Civil Rights Act, the Cuban missile crisis, the Vietnam conflict, political assassinations, the moon landing, the first televised presidential debate, “The Pill,” and, arguably, a more rapid rate of technological advancement and cultural change than ever before. The accelerated pace of change was well reflected in the art of the time, where styles and movements were almost constantly established, often in reaction to one another. This exhibition presents most of the major stylistic trends of art of the 1960s in the United States and Europe, drawn from the museum’s permanent collection. An art collection began taking shape at CSU long before there was an art museum, and art of the 1960s was an early focus. -

THE AMERICAN ART-1 Corregido

THE AMERICAN ART: AN INTRODUCTION Compiled by Antoni Gelonch-Viladegut For the Gelonch Viladegut Collection Paris-Boston, April 2011 SOMMARY INTRODUCTION 3 18th CENTURY 5 19th CENTURY 6 20th CENTURY 8 AMERICAN REALISM 8 ASHCAN SCHOOL 9 AMERICAN MODERNISM 9 MODERNIST PAINTING 13 THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST 14 HARLEM RENAISSANCE 14 NEW DEAL ART 14 ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM 15 ACTION PAINTING 18 COLOR FIELD 19 POLLOCK AND ABSTRACT INFLUENCES 20 ART CRITICS OF THE POST-WORLD WAR II ERA 21 AFTER ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM 23 OTHER MODERN AMERICAN MOVEMENTS 24 THE GELONCH VILADEGUT COLLECTION 2 http://www.gelonchviladegut.com The vitality and the international presence of a big country can also be measured in the field of culture. This is why Statesmen, and more generally the leaders, always have the objective and concern to leave for posterity or to strengthen big cultural institutions. As proof of this we can quote, as examples, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the British Museum, the Monastery of Escorial or the many American Presidential Libraries which honor the memory of the various Presidents of the United States. Since the Holy Roman Empire and, notably, in Europe during the Renaissance times cultural sponsorship has been increasingly active for the sake of art or for the sense of splendor. Nowadays, if there is a country where sponsors have a constant and decisive presence in the world of the art, this is certainly the United States. Names given to museum rooms in memory of devoted sponsors, as well as labels next to the paintings noting the donor’s name, are a very visible aspect of cultural sponsorship, especially in America. -

LEE KRASNER Public Information (Selected Chronology)

The Museum of Modern Art 79 LEE KRASNER Public Information (Selected Chronology) 1908 Born October 27, Lenore Krassner in Brooklyn, New York. 1926-29 Studies at Women's Art School of Cooper Union, New York City. 1928 Attends Art Students League. 1929-32 Attends National Academy of Design. 1934-35 Works as an artist on Public Works of Art Project and for the Temporary Emergency Relief Administration. Joins the WPA Federal Art Project as an assistant in the Mural Division. 1937-40 Studies with the artist Hans Hofmann. 1940 Exhibits with American Abstract Artists at the American Fine Arts Galleries, New York. 1942 Participates in "American and French Paintings," curated by John Graham at the McMillen Gallery, New York. As a result of the show, begins acquaintance with Jackson Pollock. 1945 Marries Jackson Pollock on October 25 at Marble Collegiate Church, New York. Exhibits in "Challenge to the Critic" with Pollock, Gorky, Gottlieb, Hofmann, Pousette-Dart, and Rothko, at Gallery 67, New York. 1946-49 Creates "Little Image" all-over paintings at Springs, Easthampton. 1951 First solo exhibition, "Paintings 1951, Lee Krasner," at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York. 1953 Begins collage works. 1955 Solo exhibition of collages at Stable Gallery, New York. 1956 Travels to Europe for the first time. Jackson Pollock dies on August 11. 1959 Completes two mosaic murals for Uris Brothers at 2 Broadway, New York. Begins Umber and Off-White series of paintings. 1965 A retrospective, "Lee Krasner, Paintings, Drawings, and Col lages," is presented at Whitechapel Art Gallery in London (circulated the following year to museums in York, Hull, Nottingham, Newcastle, Manchester, and Cardiff). -

2013 Issue #5

Flint Institute of Arts fiamagazineNOV–DEC 2013 Website www.flintarts.org Mailing Address 1120 E. Kearsley St. contents Flint, MI 48503 Telephone 810.234.1695 from the director 2 Fax 810.234.1692 Office Hours Mon–Fri, 9a–5p exhibitions 3–4 Gallery Hours Mon–Wed & Fri, 12p–5p Thu, 12p–9p video gallery 5 Sat, 10a–5p Sun, 1p–5p art on loan 6 Closed on major holidays Theater Hours Fri & Sat, 7:30p featured acquisition 7 Sun, 2p acquisitions 8 Museum Shop 810.234.1695 Mon–Wed, Fri & Sat, 10a–5p Thu, 10a–9p films 9–10 Sun, 1p–5p calendar 11 The Palette 810.249.0593 Mon–Wed & Fri, 9a–5p Thu, 9a–9p news & programs 12–17 Sat, 10a–5p Sun, 1p–5p art school 18–19 The Museum Shop and education 20–23 The Palette are open late for select special events. membership 24–27 Founders Art Sales 810.237.7321 & Rental Gallery Tue–Sat, 10a–5p contributions 28–30 Sun, 1p–5p or by appointment art sales & rental gallery 31 Admission to FIA members .............FREE founders travel 32 Temporary Adults .........................$7.00 Exhibitions 12 & under .................FREE museum shop 33 Students w/ ID ...........$5.00 Senior citizens 62+ ....$5.00 cover image From the exhibition Beatrice Wood: Mama of Dada Beatrice Wood American, 1893–1998 I Eat Only Soy Bean Products pencil, color pencil on paper, 1933 12.0625 x 9 inches Gift of Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, LLC, 2011.370 FROM THE DIRECTOR 2 I never tire of walking through the sacred or profane, that further FIA’s permanent collection galleries enhances the action in each scene. -

CONCENTRATION PAPER HELEN FRANKENTHALER Submitted by Christy L. Rezny Art Department in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

( CONCENTRATION PAPER HELEN FRANKENTHALER Submitted by Christy L. Rezny Art Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado Summer 1990 LIST OF PLATES Plate 1. Mountains and Sea. 1952 Oil on Canvas 220.1 x 297.8 cm Plate 2. Las Mayas. 1958 Oil on Canvas 254 x 109.9 cm Plate 3. Fransisco Jose de Goya y Lucientes Majas on a Balcony. c. 1800-14 Oil on Canvas 195 x 125.7 cm Plate 4. The Moors. 1963 Acrylic on Canvas 274 x 122 cm Plate 5. The Human Edge. 1967 Acrylic on Canvas 315 x 237 cm Plate 6. Nude. 1958 Oil on Canvas 257.8 x 115.6 cm Plate 7. Mother Goose Melody. 1959 Oil on canvas 208.2 x 264.1 cm The Helen Frankenthaler Retrospective which opened at the Museum of Modern Art in June 1989 represents four decades of painting. When the curators of the Retrospective asked Frankenthaler what she hoped viewers might learn from the show, she replied, "In my art I've moved and have been able to grow. I've been someplace. Hopefully, others should be similarly moved." (Carmean 1989:8) Indeed, when one gets into Frankenthal.er' s work, "One sees a basic signature that develops over the dec~des." (Carmean 1990:5) Frankenthaler was born on December 12, 1928, on New ( York's Upper East Side. She comes from a prosperous German-Jewish family; her father, Alfred Frankenthaler, was a highly respected judge in the state's Supreme Court. -

Course GA-17 WOMAN in ART: VISIONS from the PERSPECTIVES of DIFFERENCE and EQUALITY Lecturer: Dr

Course GA-17 WOMAN IN ART: VISIONS FROM THE PERSPECTIVES OF DIFFERENCE AND EQUALITY Lecturer: Dr. Magdalena Illán Martín ([email protected]) Lecturer: Dr. Lina Malo Lara ([email protected]) OBJECTIVES This Course is designed with two key objectives in mind: firstly, to contribute to the rescue from academic oblivion of the women artists who have produced creative output throughout history and who, due to a range of different conditioning factors of a social kind, have remained on the margins of the Art World; secondly, to raise awareness of, and encourage reflection about, the situation of women within the Art environment of the present day, as well as about the aims pursued by tendencies within feminist criticism, together with the compromise, at the dawn of the twenty-first century, of the woman artist in the call for gender equality in society. METHODOLOGY Class sessions will be interactively theoretical and practical, combining the theoretical exploration of syllabus content – supported by the viewing of artistic works and documentaries- with critical debate on the part of students when dealing with the on-sceen images and the recommended texts. SUBJECT BLOCK 1.: STARTING POINT Do Women Have To Be Naked To Get Into the Met. Museum? Art and Gender. Art Created by Women; Feminine Art; Feminist Art. Feminism and Post-Feminism. SUBJECT BLOCK 2.: THE DEPICTION OF THE FEMININE IN THE HISTORY OF ART Introduction: Models and Counter-Models. Woman-as-Fetish. Art and Mythology: Disguised Eroticism. Art and Religion: the Figure of Mary versus Eve. Art and Portraiture: Women of the Nobility, of the Bourgeoisie, and Nameless Faces. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Barbican Centre Board, 24/07/2019 11:00

Public Document Pack Barbican Centre Board Date: WEDNESDAY, 24 JULY 2019 Time: 11.00 am Venue: COMMITTEE ROOMS, 2ND FLOOR, WEST WING, GUILDHALL Members: Deputy Dr Giles Shilson (Chairman) Deputy Tom Sleigh (Deputy Chairman) Stephen Bediako (External Member) Russ Carr (External Member) Simon Duckworth Alderman David Graves Gerard Grech (External Member) Deputy Tom Hoffman (Chief Commoner) Deputy Wendy Hyde Emma Kane (Ex-Officio Member) Vivienne Littlechild Wendy Mead Lucy Musgrave (External Member) Graham Packham (Ex-Officio Member) Judith Pleasance Alderman William Russell Jenny Waldman (External Member) Enquiries: Leanne Murphy tel. no.: 020 7332 3008 [email protected] Lunch will be served in the Guildhall Club at 1pm N.B. Part of this meeting could be the subject of audio or visual recording John Barradell Town Clerk and Chief Executive AGENDA A number of items on the agenda will have already been considered by the Board’s Finance and/or Risk Committees and it is therefore proposed that they be approved or noted without discussion. These items have been marked with a star (*). Any Member is able to request that an item be unstarred and subject to discussion; Members are asked to inform the Town Clerk or Chairman of this request prior to the meeting. 1. APOLOGIES 2. MEMBERS' DECLARATIONS UNDER THE CODE OF CONDUCT IN RESPECT OF ITEMS ON THE AGENDA 3. MINUTES a) Board Minutes To agree the public minutes and summary of the Barbican Centre Board meeting held on 22 May 2019. For Decision (Pages 1 - 8) b) Minutes of the Finance Committee - TO FOLLOW To receive the public minutes of the Finance Committee of the Barbican Centre Board meeting held on 8 July 2019. -

The Materiality of Text and Body in Painting and Darkroom Processes: an Investigation Through Practice

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2003 The Materiality of Text and Body in Painting and Darkroom Processes: An Investigation through Practice Robinson, Deborah http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/1738 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. The Materiality of Text and Body in Painting and Darkroom Processes: An Investigation through Practice by Deborah Robinson A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Art and Design Faculty of Arts and Education June 2003 The Materiality of Text and Body in Painting and Darkroom Processes: An Investigation through Practice Deborah Claire Robinson This research study ennploys practice-based strategies through which material processes might be opened to new meaning in relation to the feminine. The purpose of the written research component is to track the material processes constituting a significant part of the research findings. Beginning with historical research into artistic and critical responses to Helen Frankenthaler's painting, Mountains and Sea, I argue that unacknowledged male desire distorted and consequently marginalised reception of her work. I then work with the painting processes innovated by Frankenthaler and relate these to a range of feminist ideas relating to the corporeal, especially those with origins in Irigaray's writings of the 1980s. -

The Loupe the Newsletter Of

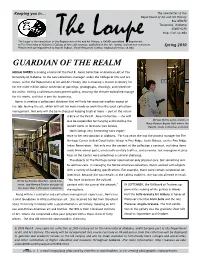

Keeping you in... The newsletter of the Department of Art and Art History Box 870270 Tuscaloosa, Alabama 35487-0270 http://art.ua.edu The Loupe is the newsletter of theThe Department of Art and Art History,Loupe a NASAD-accredited department in The University of Alabama’s College of Arts and Sciences, published in the fall, spring, and summer semesters. Spring 2010 Please send correspondence to Rachel Dobson, Visual Resources Curator, [email protected]. Guardian of the realm MIRIAM NORRIS is making a home for the Paul R. Jones Collection of American Art at The University of Alabama. As the new collections manager, under the College of Arts and Sci- ences, within the Department of Art and Art History, she is creating a master inventory list for the multi-million dollar collection of paintings, photographs, drawings, and mixed me- dia works, writing a collections management policy, securing the climate-controlled storage for the works, and that is just the beginning. Norris is creating a collections database that will help her organize another aspect of her job: loaning the art, which will call for more hands-on work than the usual collections management. Not only will she be in charge of keeping track of loans -- part of the raison d’être of the Paul R. Jones Collection -- she will also be responsible for hanging and installing the Miriam Norris opens shelves in Mary Harmon Bryant Hall where the loaned works at locations (see below). Paul R. Jones Collection is stored. Norris brings very interesting work experi- ence to her new position at Alabama. -

Masterpiece: Blue Atmosphere by Helen Frankenthaler

Masterpiece: Blue Atmosphere by Helen Frankenthaler Pronounced: Frank–en-tall-er, Helen Key words: Abstract Expressionism, color Grade: 2nd Activity: Blow Painting Meet the Artist: Born in New York and was the youngest daughter of a judge on the New York Supreme Court. Formal education at Bennington College and continued art studies in the studios of various artists, such as Ruffino Tamayo, Wallace Harrison, and Hans Hoffmann. Helen Frankenthaler is probably the most recognized and celebrated American women artists today. Frankenthaler’s rise to artistic fame was almost meteoric, beginnings with the 1952 abstract landscape know as “Mountains and Sea”. This painting is large measuring 75 feet by ten feet. It has the effect of watercolor painting, even though it is painted entirely with oils. It is this major innovation in her technique, which would reverberate throughout the art world over twenty years. “Stain painting” or soak stain” became the hallmark of her style and enabled her to create color filled canvases that seemed to float on air. In this process she poured diluted paint (with kerosene or turpentine) directly onto the unprimed surface of the canvas, allowing the color to soak into its support, rather than painting on top of the already sealed canvas as was customary. Helen Frankenthaler was very interested in Jackson Pollock’s art and his “drip” paintings liberated her way of creating art. She is view as the leader in the second generation of Abstract Expressionism, an art form to express emotion in a spontaneous way. Activity: Blow painting Prepare the Tempera Paint by deluding it a little; it should be fluid but not too watery. -

Shifting Momentum: Abstract Art from the Noyes Collection

Education Guide April 5 – June 6, 2018 Shifting Momentum: Abstract Art from the Noyes Collection Free Opening Reception: Second Friday, April 13, 2018 6:00 – 8:00 pm Curator’s Talk by Chung-Fan Chang: 6:00pm This show features abstract works by Dimitri Petrov, Lucy Glick, Robert Natkin, Jim Leuders, W.D. Bannard, Robert Motherwell, Frieda Dzubas, Alexander Liberman, David Johnston, Hulda Robbins, Wolf Kahn, Deborah Enight, Oscar Magnan, and Katinka Mann. Lucy Glick, Quiet Landing, oil on linen, 1986 Dimitri Petrov was born in Philadelphia in 1919, grew up in an anarchist colony in New Jersey and spent much of his career in Philadelphia. In 1977, he moved to Mount Washington, Massachusetts. Petrov later attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and studied printmaking with Stanley Hayter at the Atelier 17 Workshop. He was a member of the Dada movement and a Surrealist painter and printmaker. He was also the editor of a surrealist newspaper, Instead, a member of the Woodstock Artists Association, and editor/publisher of publications including the “Prospero” series of poet-artist books "Letter Edged in Black". Lucy Glick, an artist whose vividly colored paintings were known for their bold lines and sense of movement was born in Philadelphia. Glick attended the Philadelphia College of Art from 1941 to 1943 and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 1958 to 1962. Her paintings were a vehicle for expressing her emotions, usually with strong lines, energetic brush strokes and a luminous quality. Robert Natkin was born in Chicago in 1930 into a large Russian-Jewish immigrant family.