BRITISH-IRISH PARLIAMENTARY ASSEMBLY Fifty-Fifth Plenary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2015

SLIGO COUNTY COUNCIL ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ~ 0 ~ Contents Introduction by Cathaoirleach Councillor Rosaleen O’Grady ...................................................... 2 Members of Sligo County Council - 2015 ......................................................................................... 3 The late Councillor Seamie O’Boyle .................................................................................................. 4 Strategic Policy Committee Members ............................................................................................... 5 Housing and Corporate Directorate .................................................................................................. 6 Housing and Building ..................................................................................................................... 7 Corporate Services ......................................................................................................................... 14 Human Resources .......................................................................................................................... 17 Sligo Library Service and Museum ............................................................................................. 19 Public Consultation of Ireland 2016 ............................................................................................ 21 Civil Defence ................................................................................................................................... 23 Community and Enterprise -

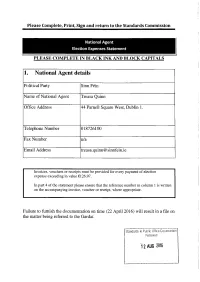

Sinn-Fein-NA-EES.Pdf

Candidate Name Constituency Amount Assigned Total Expenditure on the candidate by the national agent € € 1. Micheal MacDonncha Dublin Bay North 5000 2.Denise Mitchell Dublin Bay North 5000 3.Chris Andrews Dublin Bay South 5000 450.33 4.Mary Lou McDonald Dublin Central 4000 5.Louise O’Reilly Dublin Fingal 8000 2449.33 6. Eoin O’Broin Dublin Mid West 3000 7. Dessie Ellis Dublin North West 3000 8.Cathleen Carney Boud Dublin North West 5000 9.Sorcha Nic Cormaic Dublin Rathdown 5000 10.Aengus Ó Snodaigh Dublin South 3000 Central 11.Màire Devine Dublin South 3000 Central 12. Sean Crowe Dublin South West 3000 13.Sarah Holland Dublin South West 5000 14.Paul Donnelly Dublin West 3000 69.50 15.Shane O’Brien Dun Laoghaire 5000 73.30 16.Caoimhghìn Ó Caoláin Cavan Monaghan 3000 129.45 17.Kathryn Reilly Cavan Monaghan 3000 192.20 18.Pearse Doherty Donegal 3000 19.Pádraig MacLochlainn Donegal 3000 20.Garry Doherty Donegal 3000 21.Annemarie Roche Galway East 5000 22.Trevor O’Clochartaigh Galway West 5000 73.30 23.Réada Cronin Kildare North 5000 24.Patricia Ryan Kildare South 5000 13.75 25.Brian Stanley Laois 3000 255.55 26.Paul Hogan Longford 5000 Westmeath 27.Gerry Adams Louth 3000 28.Imelda Munster Louth 10000 29.Rose Conway Walsh Mayo 10000 560.57 30.Darren O’Rourke Meath East 6000 31.Peadar Tòibìn Meath West 3000 247.57 32.Carol Nolan Offaly 4000 33.Claire Kerrane Roscommon Galway 5000 34.Martin Kenny Sligo Leitrim 3000 193.36 35.Chris MacManus Sligo Leitrim 5000 36.Kathleen Funchion Carlow Kilkenny 5000 37.Noeleen Moran Clare 5000 794.51 38.Pat Buckley Cork East 6000 202.75 39.Jonathan O’Brien Cork North Central 3000 109.95 40.Thomas Gould Cork North Central 5000 109.95 41.Nigel Dennehy Cork North West 5000 42.Donnchadh Cork South Central 3000 O’Laoghaire 43.Rachel McCarthy Cork south West 5000 101.64 44.Martin Ferris Kerry County 3000 188.62 45.Maurice Quinlivan Limerick City 3000 46.Seamus Browne Limerick City 5000 187.11 47.Seamus Morris Tipperary 6000 1428.49 48.David Cullinane Waterford 3000 565.94 49.Johnny Mythen Wexford 10000 50.John Brady Wicklow 5000 . -

Correspondence from Chloe Smith MP, Minister For

Chloe Smith MP 70 Whitehall Minister for the Constitution London SW1A 2AS Web www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk Our Ref: MFC/1294 David Rees AM National Assembly for Wales Cardiff Bay Cardiff CF99 1NA 10 May 2018 Dear David, Meeting with the External Affairs and Additional Legislation Committee Thank you for your letter further to our meeting on 30 April, and for the additional questions from your Committee that we did not have sufficient time to cover during that session. I am grateful to you and your Committee for giving myself and Robin Walker, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Department for Exiting the European Union, the opportunity to give evidence to you on the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill and on EU exit and devolution matters more widely. I have included with this letter an Annex that sets out the answers to your detailed questions. I have endeavoured to provide this to you as swiftly as possible as I recognise the time pressures that your Committee is under to report on the Bill to the National Assembly for Wales in advance of its consideration of the legislative consent motion. As we agreed during our meeting, and as you mention in your letter, my colleague Robin Walker will write to you separately regarding nominations to the Committee of the Regions. CHLOE SMITH MP ANNEX A – RESPONSES TO QUESTIONS FROM THE COMMITTEE Questions from Dai Lloyd AM on consent decisions We can be absolutely clear that a ‘consent decision’, as defined in the Bill, does not automatically equate to a decision to grant consent. -

Minister for Parliamentary Business.Dot

Minister for UK Negotiations on Scotland’s Place in Europe Michael Russell MSP T: 0300 244 4000 E: [email protected] Mr Bruce Crawford MSP Convener Finance and Constitution Committee Scottish Parliament Edinburgh EH99 1SP ___ 04 May 2018 Dear Convener I wrote to you and to the Convener of the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Relations Committee on 30 April to alert your committees to the meeting of the Joint Ministerial Committee on EU Negotiations [JMC (EN)] on 2 May. I am now writing to report on the Scottish Government’s actions at that meeting and provide you with a copy of the Joint Communique agreed at the meeting. The other Ministers attending were: From the UK Government: the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and Minister for the Cabinet Office, Rt Hon David Lidington MP; the Secretary of State for Exiting the EU, Rt Hon David Davis MP; the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Rt Hon Karen Bradley MP; the Secretary of State for Wales, Rt Hon Alun Cairns MP; the Secretary of State for Scotland, Rt Hon David Mundell MP; the Minister for the Constitution, Chloe Smith MP; the Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Exiting the EU, Robin Walker MP. From the Welsh Government: the Cabinet Secretary for Finance, Mark Drakeford AM. From the Scottish Government: the Minister for UK Negotiations on Scotland’s Place in Europe, Michael Russell MSP. In the absence of Ministers from the Northern Ireland Executive, a senior civil servant from the Northern Ireland Civil Service was in attendance. At the meeting the Committee considered the devolved administrations’ role in the UK-EU negotiations, and discussed UK Frameworks and the EU (Withdrawal) Bill. -

Cofnod Y Trafodion the Record of Proceedings

Cofnod y Trafodion The Record of Proceedings Y Pwyllgor Cyfrifon Cyhoeddus The Public Accounts Committee 15/03/2016 Agenda’r Cyfarfod Meeting Agenda Trawsgrifiadau’r Pwyllgor Committee Transcripts Cynnwys Contents 4 Cyflwyniadau, Ymddiheuriadau a Dirprwyon Introductions, Apologies and Substitutions 4 Papurau i’w Nodi Papers to Note 5 Cronfa Buddsoddi Cymru mewn Adfywio: Trafod ymateb Llywodraeth Cymru i Adroddiad y Pwyllgor Regeneration Investment Fund for Wales: Consideration of the Welsh Government’s response to the Committee’s Report 7 Cynnig o dan Reol Sefydlog 17.42 i Benderfynu Gwahardd y Cyhoedd o’r Cyfarfod Motion under Standing Order 17.42 to Resolve to Exclude the Public from the Meeting Cofnodir y trafodion yn yr iaith y llefarwyd hwy ynddi yn y pwyllgor. Yn ogystal, cynhwysir trawsgrifiad o’r cyfieithu ar y pryd. The proceedings are reported in the language in which they were spoken in the committee. In addition, a transcription of the simultaneous interpretation is included. 15/03/2016 Aelodau’r pwyllgor yn bresennol Committee members in attendance Mohammad Asghar Ceidwadwyr Cymreig Bywgraffiad|Biography Welsh Conservatives Jocelyn Davies Plaid Cymru Bywgraffiad|Biography The Party of Wales Mike Hedges Llafur Bywgraffiad|Biography Labour Sandy Mewies Llafur Bywgraffiad|Biography Labour Darren Millar Ceidwadwyr Cymreig (Cadeirydd y Pwyllgor) Bywgraffiad|Biography Welsh Conservatives (Committee Chair) Julie Morgan Llafur Bywgraffiad|Biography Labour Eraill yn bresennol Others in attendance Mark Jones Swyddfa Archwilio Cymru Wales Audit Office Alistair McQuaid Swyddfa Archwilio Cymru Wales Audit Office Matthew Mortlock Swyddfa Archwilio Cymru Wales Audit Office Huw Vaughan Thomas Archwilydd Cyffredinol Cymru Auditor General for Wales Swyddogion Cynulliad Cenedlaethol Cymru yn bresennol National Assembly for Wales officials in attendance Fay Buckle Clerc Clerk Claire Griffiths Dirprwy Glerc Deputy Clerk Joanest Varney- Uwch-gynghorydd Cyfreithiol Jackson Senior Legal Adviser Dechreuodd y cyfarfod am 09:00. -

74 Dáil Éireann

(Second Supplementary Order Paper) 74 DÁIL ÉIREANN Dé Máirt, 1 Nollaig, 2020 Tuesday, 1st December, 2020 2 p.m. GNÓ COMHALTAÍ PRÍOBHÁIDEACHA PRIVATE MEMBERS' BUSINESS Fógra i dtaobh Leasú ar Thairiscint: Notice of Amendment to Motion [Please note: there is a change to the text of the Sinn Féin motion highlighted in bold on today’s Second Supplementary Order Paper.] 109. “That Dáil Éireann: notes that: — in five weeks’ time the pension age is due to increase to 67 years of age on 1st January, 2021; — legislation needed to stop the pension age increasing to 67 in January has not passed through the House; — every worker in the State makes a considerable tax contribution throughout their working life and should have the right to retire at 65; — some workers want to retire at 65, while others want to remain at work, where they are able and willing to do so; — numerous employment contracts stipulate an end of employment date in line with when an employee turns 65; — since the abolition of the State Pension Transition payment, thousands of 65-year olds have had to sign on for a Jobseeker’s payment; — there are now over 4,000 65-year olds in receipt of either Jobseeker’s Allowance or Jobseeker’s Benefit; — there is a difference of €45.30 between the Jobseeker payments and the State Pension leading to an annual loss of €2,355.60; and — the pension age is scheduled in legislation to increase to 67 years in 2021, and 68 years in 2028; and calls on the Government to: — restore the State Pension Transition payment for those retiring at 65 years of age; — abolish mandatory retirement (with exceptions for security-related employment) to give workers the choice to work or retire so long as they are fit to do so; P.T.O. -

Our Taoiseach Really Needs a Lesson in Checking His Privilege

Irish Examiner 12 Opinion Friday, 20.10.2017 Our Taoiseach really needs a Established 1841 Abortion law lesson in checking his privilege URELY there was someone Dr Peter Boylan, left, warned of deaths Early vote somewhere, a man even, and Prof Sabaratnam Arulkumaran willing to point out to the Taoiseach that he’s big has little time for our official abortion time storing up trouble with Irish approach. Pictures: Gareth Chaney/Collins women the way that he’s going on. undermines Take one woman, me for instance, sitting for hour after issues. The Harvey Weinstein affair hour watching the Oireachtas com- has been gripping the Western mittee on the Eighth Amendment, world, showing that even the where eminent medics, with world’s richest and seemingly most work to date decades of experience at the front- powerful women, can fall prey to line of obstetrics, make clear the the most horrendous sexual viol- absolute disservice that has been ence. If you’d a lick of political THE all-party Oireachtas committee examining Ireland’s done, and continues to be done, to sense you wouldn’t need a brand abortion law took many people by surprise when it voted Irish women. new communications unit overwhelmingly against retaining the Eighth Amendment In the background bubbling to realise this is a particularly sen- to the Constitution in its present form while still having five away is another box in the teeth for sitive topic at present; that it’s not weeks of debate on the issue to run. women — the controversy over the best optics to be getting all the In doing so, the Committee on the Eighth Amendment to pensions impacting an estimated best boy toys when it comes to the Constitution, as it was formally known, has made itself all 35,000 females who took time out showing yourself in the best light, but redundant. -

Seanad Éireann

Vol. 250 Wednesday, No. 6 23 February 2017 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES SEANAD ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Insert Date Here 23/02/2017A00100Business of Seanad 371 23/02/2017A00225Commencement Matters 372 23/02/2017A00250Schools Building Projects �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������372 23/02/2017B00400Road Projects 373 23/02/2017C00400General Register Office 375 23/02/2017D00400Cancer Services Provision 377 23/02/2017G00100Order of Business 380 23/02/2017L01700Intoxicating Liquor (Amendment) Bill 2017: First Stage ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������390 23/02/2017M00100Establishment of Special Committee on Withdrawal of United Kingdom from European Union: Motion 390 23/02/2017M00500Business of Seanad 392 23/02/2017W00100The Diaspora: Statements �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������392 SEANAD ÉIREANN Déardaoin, 23 Feabhra 2017 -

Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer HM Treasury 1 Horse Guards Road London SW1A 2HQ

Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer HM Treasury 1 Horse Guards Road London SW1A 2HQ Dear Chancellor, Budget Measures to Support Hospitality and Tourism We are writing today as members and supporters of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Hospitality and Tourism ahead of the Budget on 3rd March. As you will of course be aware, hospitality and tourism are vital to the UK’s economy along with the livelihoods and wellbeing of millions of people across the UK. The pandemic has amplified this, with its impacts illustrating the pan-UK nature of these sectors, the economic benefits they generate, and the wider social and wellbeing benefits that they provide. The role that these sectors play in terms of boosting local, civic pride in all our constituencies, and the strong sense of community that they foster, should not be underestimated. It is well-established that people relate to their local town centres, high streets and community hubs, of which the hospitality and tourism sectors are an essential part. The latest figures from 2020 highlight the significant impact that the virus has had on these industries. In 2020, the hospitality sector has seen a sales drop of 53.8%, equating to a loss in revenue of £72 billion. This decline has impacted the UK’s national economy by taking off around 2 percentage points from total GDP. For hospitality, this downturn is already estimated to be over 10 times worse than the impact of the financial crisis. It is estimated that employment in the sector has dropped by over 1 million jobs. -

Publishing Government Legal Advice Table of Contents 1

Library Briefing Publishing Government Legal Advice Table of Contents 1. Law Officers’ Legal Summary Advice to the Government In the UK, law officers of the crown are responsible for providing legal advice 2. Iraq War and the to the government. Successive governments have observed a long-standing Publication of Legal convention that the advice they receive from law officers is not disclosed Advice outside government. This House of Lords Library Briefing provides a brief 3. Legal Advice on overview of the role of the law officers and the convention on the publication Military Action Post-Iraq of their advice. It also gives examples of how the Government has referred to Conflict the convention in response to calls for it to make public the full advice that it 4. Brexit had received from law officers. The final section discusses demands for the Government to publish the legal advice that it has been given regarding Brexit. Over recent weeks, there have been repeated calls—including from Labour, the Liberal Democrats, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and a former Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union—for the Government to publish in full the legal advice it has received about its proposed Brexit deal. On 13 November 2018, a binding motion for a return was agreed without division in the House of Commons, calling for “any legal advice in full, including that provided by the Attorney General, on the proposed withdrawal agreement on the terms of the UK’s departure from the European Union including the Northern Ireland backstop and framework for a future relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union” to be laid before Parliament. -

Faith and the Pandemic: the Impact of Covid-19 on Faith Communities Wednesday 25 November 2020 from 12.00 – 13.15 Via Zoom Present: 1

Minutes of the Cross-Party Group on Faith meeting Faith and the Pandemic: The Impact of Covid-19 on Faith Communities Wednesday 25 November 2020 from 12.00 – 13.15 via Zoom Present: 1. Adrian Allabarton 2. Ainsley Griffiths, Church in Wales 3. Alaa Khundakji, Muslim Council of Wales (Speaker) 4. Alan Lansdown 5. Angela Keller, Wales Adviser for the Catholic Church 6. Beverley Smith 7. Brian Reardon, Church in Wales 8. Carol Wardman, Church in Wales 9. Carys Mosely 10. Curtis Shea, Office of Darren Millar MS 11. Darren Millar AS (Chair) 12. David Emery, Salvation Army 13. Fred Till 14. Gethin Rhys 15. Jim Stewart (secretary and note taker) 16. John Kay 17. Joshua Chohan, Office of Suzy Davies MS 18. Julian Richards, New Wine Cymru (Speaker) 19. Mark Isherwood MS 20. Mark Simpson 21. Moawia Bin-Sufyan 22. Peredur Owen Griffiths, Cytûn 23. Rachel Hosgood 24. Ralph Upton 25. Rheinallt Thomas 26. Ryland Doyle 27. Sian Rees, Evangelical Alliance Wales 28. Simon Lloyd, Chief Executive of the Representative Body of the Church in Wales 29. Simon Plant 30. Siva Sivapalan, Sri Lankan community / Hindu Council of Wales 31. Wynne Roberts, NHS chaplain Apologies: 1. Andrew Misell, CEO of Alcohol Concern 2. Colin Heyman, member of the Jewish community 3. Dai Lloyd AS 4. Kate McColgan, Chair of the Interfaith Council of Wales and member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints community 5. Llyr Gruffydd AS 6. Major Peter Harrison, the Armed forces community 7. Stanley Soffa, member of the Jewish community Minutes: 1. -

Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999

TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 TOGHCHÁIN ÁITIÚLA, 1999 LOCAL ELECTIONS, 1999 Volume 1 DUBLIN PUBLISHED BY THE STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased through any bookseller, or directly from the GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS SALE OFFICE, SUN ALLIANCE HOUSE, MOLESWORTH STREET, DUBLIN 2 £12.00 €15.24 © Copyright Government of Ireland 2000 ISBN 0-7076-6434-9 P. 33331/E Gr. 30-01 7/00 3,000 Brunswick Press Ltd. ii CLÁR CONTENTS Page Foreword........................................................................................................................................................................ v Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... vii LOCAL AUTHORITIES County Councils Carlow...................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Cavan....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Clare ........................................................................................................................................................................ 12 Cork (Northern Division) .......................................................................................................................................... 19 Cork (Southern Division).........................................................................................................................................