Splenic Trauma: Endovascular Treatment Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surgical Case Conference

Surgical Case Conference HENRY R. GOVEKAR, M.D. PGY-2 UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO HOSPITAL Objectives Introduce Patient Hospital Course Management of Injuries Decisions to make Outcome History and Physical 50y/o M who was transferred to Denver Health on post injury day #3. Patient involved in motorcycle collision in Vail; admit to local hospital. Patient riding with female companion, tight turn, laid down the bike on road, companion landing on top of patient. Companion suffered minor injuries including abrasions and knee pain History and Physical Our patient – c/o Right shoulder pain, left flank pain PMH: GERD; peptic ulcer PSH: hx of surgery for intractable ulcerative disease – distal gastrectomy with Billroth I, ? Of revision to Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy Meds: prilosec Social: denies tobacco; quit ETOH 13 years ago after MVC; denies IVDA NKDA History and Physical Exam per OSH: a&ox3, minor distress HR 110’s, BP 130/70’s, on NRB mask with sats 98% Multiple abrasions on scalp, arms , knees c/o right arm pain, left sided flank pain No other obvious injuries After fluid resuscitation – HD stable Sent to CT for abd/pelvis Post 10th rib fx Grade 3 splenic laceration Spleen Injury Scale Grade I Injury Grade IV injury http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/373694-media Grade V injury http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/373694-media What should our plan be? Management of Splenic Injuries Stable vs. Unstable Unstable – OR Stable – abd CT scan CT scan Other significant injury – OR Documented splenic injury Grade I, -

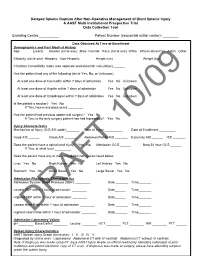

Delayed Splenic Rupture After Non-Operative Management of Blunt Splenic Injury a AAST Multi-Institutional Prospective Trial Data Collection Tool

Delayed Splenic Rupture After Non-Operative Management of Blunt Splenic Injury A AAST Multi-Institutional Prospective Trial Data Collection Tool Enrolling Center:__________ Patient Number (sequential within center): ________ Data Obtained At Time of Enrollment Demographics and Past Medical History Age: ______ (years) Gender (circle one): Male Female Race (circle one): White African-American Asian Other Ethnicity (circle one): Hispanic Non-Hispanic Height (cm) _______ Weight (kg) ______ Charlson Comorbidity Index (see separate worksheet for calculation) ______ Has the patient had any of the following (circle Yes, No, or Unknown): At least one dose of Coumadin within 7 days of admission Yes No Unknown At least one dose of Aspirin within 7 days of admission Yes No Unknown At least one dose of Clopidrogrel within 7 days of admission Yes No Unknown Is the patient a smoker? Yes No If Yes, how many pack-years ________ Has the patient had previous abdominal surgery? Yes No If Yes, is the only surgery patient has had laproscopic? Yes No Injury Characteristics Mechanism of Injury (ICD-9 E-code):_______ Date of Injury __________ Date of Enrollment _________ Head AIS ______ Chest AIS _______ Abdomen/Pelvis AIS _______ Extremity AIS ______ ISS _______ Does the patient have a spinal cord injury? Yes No Admission GCS ______ Best 24 hour GCS ______ If Yes, at what level _________ Does the patient have any of the intra-abdominal injuries listed below: Liver Yes No Right Kidney Yes No Left Kidney Yes No Stomach Yes No Small Bowel Yes No Large Bowel Yes -

Spleen Trauma

Guideline for Management of Spleen Trauma Minor injury HDS Ward Observation Grade I - II STICU Observation Hemodynamically Contrast- Moderate Stable enhanced CTS Injury +/- local HDS exploration in SW Grade III-V Contrast extravasation Angioembolization (A/E) Pseudoaneurysm Spleen Injury Ongoing bleeding HDS DeteriorationGrade I - II Unstable Unsuccessful or rebleeding Hemodynamically Splenectomy Repeat eFAST Positive Laparotomy eFAST Unstable Unstable CBC, ABG, Lactate POC INR Stable Type and Cross Splenic salvage or splenectomy Negative Positive Consider DPA Negative Evaluate for other causes of instability Guideline for Management of Spleen Trauma -NOM in splenic injuries is contraindicated in the setting of unresponsive hemodynamic instability or other indicates for laparotomy (peritonitis, hollow organ injuries, bowel evisceration, impalement) -AG/AE may be considered the first-line intervention in patients with hemodynamic stability and arterial blush on CT scan irrespective from injury grade - Age above 55 years old, high ISS, and moderate to severe splenic injuries are prognostic factors for NOM failure. -Age above 55 years old alone, large hemoperitoneum alone, hypotension before resuscitation, GCS < 12 and low-hematocrit level at the admission, associated abdominal injuries, blush at CT scan, anticoagulation drugs, HIV disease, drug addiction, cirrhosis, and need for blood transfusions should be taken into account, but they are not absolute contraindications for NOM but are at higher risk of failure and STICU observation is -

Management of Adult Blunt Splenic Trauma

Review Article The Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and Critical Care Western Trauma Association (WTA) Critical Decisions in Trauma: Management of Adult Blunt Splenic Trauma Frederick A. Moore, MD, James W. Davis, MD, Ernest E. Moore, Jr., MD, Christine S. Cocanour, MD, Michael A. West, MD, and Robert C. McIntyre, Jr., MD 09/30/2020 on BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Ypodx1mzGi19a2VIGqBjfv9YfiJtaGCC1/kUAcqLCxGtGta0WPrKjA== by http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma from Downloaded J Trauma. 2008;65:1007–1011. Downloaded his is a position article from members of the Western geons were focused on perfecting operative splenic salvage from 1–3 http://journals.lww.com/jtrauma Trauma Association (WTA). Because there are no pro- techniques, the pediatric surgeons provided convincing Tspective randomized trials, the algorithm (Fig. 1) is evidence that the best way to salvage the spleen was not to based on the expert opinion of WTA members and published operate.4–6 Adult trauma surgeons were slow to adopt non- observational studies. We recognize that variability in deci- operative management (NOM) because early reports of its sion making will continue. We hope this management algo- use in adults documented a 30% to 70% failure rate of which by rithm will encourage institutions to develop local protocols two-thirds underwent total splenectomy.7–10 There was also a BhDMf5ePHKav1zEoum1tQfN4a+kJLhEZgbsIHo4XMi0hCywCX1AWnYQp/IlQrHD3Ypodx1mzGi19a2VIGqBjfv9YfiJtaGCC1/kUAcqLCxGtGta0WPrKjA== based on the resources that are available and local expert concern about missing serious concomitant intra-abdominal consensus opinion to apply the safest, most reliable manage- injuries.11–13 However, with increasing experience with NOM, ment strategies for their patients. What works at one institu- recognition that negative laparotomies caused significant tion may not work at another. -

Delayed Complications of Nonoperative Management of Blunt Adult Splenic Trauma

PAPER Delayed Complications of Nonoperative Management of Blunt Adult Splenic Trauma Christine S. Cocanour, MD; Frederick A. Moore, MD; Drue N. Ware, MD; Robert G. Marvin, MD; J. Michael Clark, BS; James H. Duke, MD Objective: To determine the incidence and type of de- Results: Patients managed nonoperatively had a sig- layed complications from nonoperative management of nificantly lower Injury Severity Score (P<.05) than adult splenic injury. patients treated operatively. Length of stay was signifi- cantly decreased in both the number of intensive care Design: Retrospective medical record review. unit days as well as total length of stay (P<.05). The number of units of blood transfused was also signifi- Setting: University teaching hospital, level I trauma center. cantly decreased in patients managed nonoperatively (P<.05). Seven patients (8%) managed nonoperatively Patients: Two hundred eighty patients were admitted developed delayed complications requiring interven- to the adult trauma service with blunt splenic injury dur- tion. Five patients had overt bleeding that occurred at ing a 4-year period. Men constituted 66% of the popu- 4 days (3 patients), 6 days (1 patient), and 8 days (1 lation. The mean (±SEM) age was 32.2±1.0 years and the patient) after injury. Three patients underwent sple- mean (±SEM) Injury Severity Score was 22.8±0.9. Fifty- nectomy, 1 had a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm nine patients (21%) died of multiple injuries within 48 embolization, and 1 had 2 areas of bleeding emboliza- hours and were eliminated from the study. One hun- tion. Two patients developed splenic abscesses at dred thirty-four patients (48%) were treated operatively approximately 1 month after injury; both were treated within the first 48 hours after injury and 87 patients (31%) by splenectomy. -

Splenic Injury with Subcapsular Hematoma and Pseudoaneurysms

Splenic Injury and Pseudoaneurysms in a Traumatic Setting Yakira Alford December 11th, 2019 RAD 4001 Dr. Ronald Bilow Clinical History • 65-year old male involved in a motor vehicle accident • Restrained driver in driver-side collision going 40 mph; 12-inch intrusion, extrication required • Per EMS – GCS 10, + LOC, • LifeFlighted as a level 1 trauma for higher level of care • Per EMS: GCS 10, +LOC • Vital Signs in ED: Temp 98.5°F HR 118 bpm BP 122/50 mm Hg RR 22/min SpO2 100% • Physical exam • Head: normocephalic, small laceration lateral to the left eye, abrasion with moderate hematoma to the left occipital region • Neuro: GCS 13, sensory/motor intact • Cardiovascular: Tachycardic, regular rhythm • Chest wall: Chest wall diffusely tender to palpation • Abdomen: soft, nontender, non-distended • Back: diffusely tender to palpation, no step-offs • FAST negative McGovern Medical School ACR appropriateness Criteria McGovern Medical School Cost of Imaging at Memorial Hermann (Typical Charges) CT Chest w/ contrast $3,936 CT Pelvis/Abdomen w/ $7,998 contrast CT Brain w/o contrast (x4) $3,157 (x4) CT Maxillofacial area w/o $4,409 contrast CT cervical spine w/o contrast $4,507 CT angiography neck w/ $2,666 contrast CT Right Tibula/Fibula w/o $3,078 contrast Total $39,222 McGovern Medical School Imaging – Full-Body CT Scan • CT chest, abdomen n and pelvis with IV contrast, 08/22/2019 • Also Brain CT, CT Neck, CT cervical spine, CT Right Tibula and Fibula, • Axial, sagittal, and coronal views obtained • Arterial phase • 20-30 seconds after IV contrast administration • Portal venous phase • 60-80 seconds after IV contrast administration • Delayed phase • 6-10 minutes after IV contrast administration McGovern Medical School Imaging – CT Scan (Abdomen) Normal Abnormal Left kidney Liver Liver Stomach Spleen Spleen https://ddxof.com/ct-interpretation-abdomenpelvis/ McGovern Medical School CT Abdomen - Axial Axial view of the abdomen in arterial phase. -

Liver Spleen Operative Management

PRACTICE GUIDELINE Effective Date: 6-18-04 Manual Reference: Deaconess Trauma Services TITLE: OPERATIVE MANAGEMENT OF LIVER / SPLENIC INJURIES PURPOSE . To define when operative management of liver and/or splenic injuries are safe and desirable. To define a clinical pathway for the operative management of liver and/or splenic injuries. DEFINITIONS LIVER Grade I Hematoma: Subcapsular: <10% surface area Grade I Laceration: Capsular tear: <1 cm parenchymal depth Grade II Hematoma: Subcapsular: 10-50% surface area; intraparenchymal: <10cm in diameter Grade II Laceration: Capsular tear: 1-3cm; parenchymal depth: <10 cm length Grade III Hematoma: Subcapsular: >50% surface area or expanding or ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal hematoma; intraparenchymal hematoma >10 cm or expanding Grade III Laceration: >3 cm parenchymal depth Grade IV Laceration: Parenchymal disruption involving 25-75% of hepatic lobe or 1-3 Couinaud segments Grade V Laceration: Parenchymal disruption of >75 percent of a hepatic lobe, >3 segments within a single lobe. Vascular: juxtahepatic venous injuries (retrohepatic vena cava, central major hepatic veins) Grade VI – Hepatic avulsion SPLEEN Grade I Hematoma: Subcapsular: <10% surface area Grade I Laceration: Capsular tear: <1 cm parenchymal depth Grade II Hematoma: Subcapsular: 10-50% surface area Grade II Laceration: Intraparenchymal: <5 cm in diameter; capsular tear, 1-3 cm parenchymal depth which does not involve a trabecular vessel Grade III Hematoma: Subcapsular: >50% surface area or expanding Grade III Laceration: Ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal hematoma: intraparenchymal hematoma >5 cm or expanding >3 cm parenchymal depth or involving trabecular vessels Grade IV Laceration: Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels producing major devascularization (>25% of spleen) Grade V Laceration: Vascular: completely shattered spleen or hilar vascular injury which devascularizes spleen 1 GUIDELINES 1. -

The Impact of Obesity on Severity of Solid Organ Injury in the Adult

Open access Original article Trauma Surg Acute Care Open: first published as 10.1136/tsaco-2019-000318 on 12 July 2019. Downloaded from The impact of obesity on severity of solid organ injury in the adult population at a Level I trauma center Allen K Chen, David Jeffcoach, John C Stivers, Kyle A McCullough, Rachel C Dirks, Ryland J Boehnke, Lawrence Sue, Amy M Kwok, Mary M Wolfe, James W Davis Department of Surgery, ABSTRact of stay (LOS), and pulmonary dysfunction found University of San Francisco- Background The obese (body mass index, BMI > in obese patients with trauma. However, a recent Fresno, Fresno, California, USA 30) have been identified as a subgroup of patients in study evaluated the impact of obesity on solid organ regards to traumatic injuries. A recent study found that injury among pediatric patients.4 Vaughan et al, Correspondence to Dr Allen K Chen, Department high-grade hepatic injuries were more common in obese performed a multi-centered prospective analysis, of Surgery, University of San than non-obese pediatric patients. This study seeks to evaluating 117 pediatric patients with solid organ Francisco-Fresno, Fresno, evaluate whether similar differences exist in the adult injury after blunt abdominal trauma, and found California 93721, USA; achen@ population and examine differences in operative versus pediatric obese patients were more likely to sustain fresno. ucsf. edu non-operative management between the obese and non- a high-grade hepatic injury (grade 4 or 5) with Preliminary results presented obese in blunt abdominal trauma. no difference in the rate of severe splenic injury. October 4, 2017, at the Methods Patient with trauma evaluated at an Boulanger et al also evaluated solid organ injury in Committee on Trauma, American American College of Surgeons verified Level I trauma the obese adult population and reported a decrease Collegeof Surgery, Oakland, CA. -

Nontraumatic Splenic Rupture

CASE REPORT Nontraumatic Splenic Rupture Nana Sefa, MD, MPH; Ananda V. Pandurangadu, MD; Amanda Mann, MD; Amit Bahl, MD, MPH A 25-year-old man presented for evaluation of lightheadedness as well as pain in his left shoulder, epigastric region, and right flank. Case pallor. His head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat; A 25-year-old college student presented to cardiac; pulmonary; and neurological ex- the ED following a near-syncopal episode. aminations were normal. The abdominal ex- The patient stated he had felt lightheaded amination revealed a soft, minimally tender and had fallen to his knees immediately af- epigastrium but with normal bowel sounds. ter taking a shower earlier that morning, but Initial laboratory studies were remarkable did not experience any loss of consciousness for low hemoglobin (Hgb; 12.0 g/dL) and or injury. He denied a history of syncope or elevated aspartate transaminase (105 U/L), any recent trauma or fatigue. A review of the alanine aminotransferase (168 U/L), total patient’s systems was negative. His medical bilirubin (1.6 mg/dL), and glucose (179 mg/ history was remarkable for irritable bowel dL) levels. The patient’s troponin I and li- syndrome; he had no surgical history. Re- pase levels were within normal range. An garding his social history, he admitted to oc- electrocardiogram was unremarkable. casional alcohol use but denied any tobacco Given the patient’s elevated hepatic en- or illicit drug use. He was not on any current zymes, right upper quadrant ultrasound was prescription or over-the-counter medica- obtained, which demonstrated a normal tions and denied any allergies. -

Selective Nonoperative Management of Blunt Splenic Injury: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma Practice Management Guideline

GUIDELINE Selective nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline Nicole A. Stassen, MD, Indermeet Bhullar, MD, Julius D. Cheng, MD, Marie L. Crandall, MD, Randall S. Friese, MD, Oscar D. Guillamondegui, MD, Randeep S. Jawa, MD, Adrian A. Maung, MD, Thomas J. Rohs, Jr, MD, Ayodele Sangosanya, MD, Kevin M. Schuster, MD, Mark J. Seamon, MD, Kathryn M. Tchorz, MD, Ben L. Zarzuar, MD, and Andrew J. Kerwin, MD BACKGROUND: During the last century, the management of blunt force trauma to the spleen has changed from observation and expectant management in the early part of the 1900s to mainly operative intervention, to the current practice of selective operative and nonoperative man- agement. These issues were first addressed by the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) in the Practice Management Guidelines for Non-operative Management of Blunt Injury to the Liver and Spleen published online in 2003. Since that time, a large volume of literature on these topics has been published requiring a reevaluation of the current EAST guideline. METHODS: The National Library of Medicine and the National Institute of Health MEDLINE database was searched using Pub Med (www.pubmed.gov). The search was designed to identify English-language citations published after 1996 (the last year included in the previous guideline) using the keywords splenic injury and blunt abdominal trauma. RESULTS: One hundred seventy-six articles were reviewed, of which 125 were used to create the current practice management guideline for the selective nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury. -

Blunt Trauma

Multisystem Trauma Objectives Describe the pathophysiology and clinical manifestations of multisystem trauma complications. Describe the risk factors and criteria for the multisystem trauma patient. Describe the nursing management of the patient recovering from multisystem trauma. Describe the collaboration with the interdisciplinary teams caring for the multisystem trauma patient. Multisystem Trauma Facts Leading cause of death among children and adults below the age of 45 4th leading cause of death for all ages Accounts for approximately 170,000 deaths each year and over 400 deaths per day Affects mostly the young and the old Kills more Americans than stroke and AIDS combined Leading cause of disability Costs: 100 billion dollars to U.S. society annually Research dollars only 4% of U.S. federal research dollars Most traumas are preventable! Who Is a Trauma Patient? Evidence-Based Categories: Physiologic Criteria Mechanism of Injury Criteria Patient/Environmental Criteria Anatomic Criteria mc.vanderbilt.edu Umm.edu Physiologic Criteria Systolic blood pressure <90mm HG Respiratory rate 10 or >29 per minute Glasgow Coma Scale score <14 Nremtacademy.com Anatomic Criteria Penetrating injuries to the head, neck, torso or proximal extremities 2 or more obvious femur or humerus fractures Amputation above the waist or ankle Crushed, de-gloved or mangled extremities Open or depressed skull fracture Unstable chest wall (flail chest) Paralysis Pelvic fracture www.pulmccrn.org Mechanism of Injury Criteria Blunt Trauma: -

Pediatric Trauma

Pediatric Trauma Amy Henry, RN, CFRN “If a disease were killing our children in the proportions that injuries are, people would be outraged and demand that this killer be stopped.” -C. Everett Koop, MD Pediatric Trauma Trauma is the leading cause of childhood death and disability in the US. On average 12,175 deaths annually! (CDC) • Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the most common cause. • Chest Trauma ~ second. • Abdominal injuries rank third as a cause of traumatic death. Mechanisms of Injury The transfer of kinetic energy arises from several sources: – Blunt (injury to internal organs) – Penetrating (disruption of skin and organ integrity) – Acceleration-Deceleration (abrupt, forceful back and forth movement) – Crushing (direct compression of body structures) Epidemiology • Blunt trauma accounts for more than 80% of all pediatric injuries • External evidence of injury may be minimal as energy is often absorbed by underlying structures. • Must suspect underlying potential injuries! 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 Blunt Penetrating Crush Other Blunt Force Trauma 1. Falls 2. Motor Vehicle Crashes 3. Car vs. Pedestrian Crashes 4. Bicycle Crashes 5. Skateboarding Injuries 6. Infant Walker – Related Injuries 7. Sledding Injuries Mechanism of Injury Knowledge of the Mechanism of Injury allows for a high index of suspicion for the resultant injuries in the child. Initial Trauma Assessment and Intervention Primary Assessment Identify life-threatening injuries. Focus should be on airway, breathing, circulatory and neurologic systems. Secondary Assessment Identify injuries to the remaining body systems. Not life threatening but may have long term consequences. Primary Assessment 1. Assess the Airway and Cervical Spine 2.