Taking a Deeper Dive Into Progressive Prosecution: Evaluating the Trend Through the Lens of Geography: Part Two: External Constraints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transcript Decarceration Nation Episode 67: Rachael Rollins

Transcript Decarceration Nation Episode 67: Rachael Rollins Josh Hoe 0:03 Hello and welcome to this episode and a special set of episodes of the decarceration nation podcast from the Smart on Crime innovations conference in New York City. I say we because I'm thrilled that our web guru Robert Alvarez was able to join me in New York City for the conference. As result, Robert and I got to interview several thought leaders in the criminal justice reform field. The episode you're about to hear is one of a series of five interviews, which will be releasing over the next two and a half weeks. Each episode will be intentionally shorter than our normal episodes running for this they'll probably be running between 20 and 30 minutes. Okay, here we go. I hope you enjoy the special Decarceration Nation Podcast episodes from the 2019 Smart on Crime conference. Robert Alvarez 0:49 Hello, this is Robert Alvarez and I'm here with Josh Hoe We are Decarceration Nation and we're live from the Smart on Crime innovations conference 2019 at john Jay College will be Introducing Rachael Rollins. She is the district attorney of Suffolk County in Massachusetts, which includes the municipalities of Boston, Chelsea, revere and winter. Josh? Josh Hoe Welcome to the Decarceration Nation. Rachel, Rachael Rollins 1:12 Thanks for having me here. Josh Hoe 1:14 Yeah, it's great to have you here. I'm going to start off in kind of a weird place because we have more important things to discuss. -

When Prosecutors Politick: Progressive Law Enforcers Then and Now

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 110 Issue 4 Fall Article 3 Fall 2020 When Prosecutors Politick: Progressive Law Enforcers Then and Now Bruce A. Green Rebecca Roiphe Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Bruce A. Green and Rebecca Roiphe, When Prosecutors Politick: Progressive Law Enforcers Then and Now, 110 J. CRIM. L. & CRIMINOLOGY 719 (2020). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol110/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-4169/20/11004-0719 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 110, No. 4 Copyright © 2020 by Bruce A. Green & Rebecca Roiphe Printed in U.S.A. WHEN PROSECUTORS POLITICK: PROGRESSIVE LAW ENFORCERS THEN AND NOW BRUCE A. GREEN & REBECCA ROIPHE* A new and recognizable group of reform-minded prosecutors has assumed the mantle of progressive prosecution. The term is hard to define in part because its adherents embrace a diverse set of policies and priorities. In comparing the contemporary movement with Progressive Era prosecutors, this Article has two related goals. First, it seeks to better define progressive prosecution. Second, it uses a historical comparison to draw some lessons for the current movement. Both groups of prosecutors were elected on a wave of popular support. Unlike today’s mainstream prosecutors who tend to campaign and labor in relative obscurity, these two sets of prosecutors received a good deal of popular attention and support. -

As We Begin the Year

Sheriff’s Statement Index As we begin the Year 2019, I’d like to offer SCSD Hosts 2nd City Council Hearing my sincere appreciation For only the second time, the Suffolk County for the custody and non- Sheriff’s Department welcomed the Boston custody staff members who City Council into the House of Correction demonstrate dedication, for a hearing on incarceration, recidivism commitment and pride for and reentry. the work they do on a daily basis to ensure that the Suffolk County Sheriff’s Department continues to be one of the best law enforcement organizations in the country. Additionally, I’d like to thank all of the hardworking providers, volunteers and concerned citizens who continue to work with us to maintain services and programming of the highest quality to the people in our care and custody in an effort to help them to become better equipped to provide for themselves and their families upon their return to society. The goals that we’ve achieved and the new programming that we’ve Department’s O.A.S.I.S. Unit Unveiled introduced this year were made possible by all of the Department Earlier this year, the Department opened the staff, practitioners and supporters who joined together in the O.A.S.I.S. (Opioid and Addiction Services common cause of rehabilitation, reinvention and reintegration of Inside South Bay) Unit to provide intensive the men and women remanded to our care and custody. Many substance abuse treatment and discharge thanks to you all for all of your efforts, and I wish you great planning services to male pretrial detainees. -

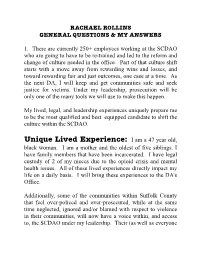

ACLU Questionairre ROLLINS

RACHAEL ROLLINS GENERAL QUESTIONS & MY ANSWERS 1. There are currently 250+ employees working at the SCDAO who are going to have to be re-trained and led to the reform and change of culture needed in the office. Part of that culture shift starts with a move away from rewarding wins and losses, and toward rewarding fair and just outcomes, one case at a time. As the next DA, I will keep and get communities safe and seek justice for victims. Under my leadership, prosecution will be only one of the many tools we will use to make this happen. My lived, legal, and leadership experiences uniquely prepare me to be the most qualified and best equipped candidate to shift the culture within the SCDAO. Unique Lived Experience: I am a 47 year old, black woman. I am a mother and the oldest of five siblings. I have family members that have been incarcerated. I have legal custody of 2 of my nieces due to the opioid crisis and mental health issues. All of these lived experiences directly impact my life on a daily basis. I will bring these experiences to the DA’s Office. Additionally, some of the communities within Suffolk County that feel over-policed and over-prosecuted, while at the same time neglected, ignored and/or blamed with respect to violence in their communities, will now have a voice within, and access to, the SCDAO under my leadership. Their (as well as everyone else’s) comments, complaints and suggestions will be heard and addressed. Relevant Legal Experience: I have been a practicing lawyer for 20+ years. -

REIMAGINING PROSECUTION: a Growing Progressive Movement

REIMAGINING PROSECUTION: A Growing Progressive Movement Angela J. Davis About the Author Angela J. Davis is a Professor at American University Washington College of Law and a former director of the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia. She thanks Meagan Allen and Philip Green for their research assistance. Abstract Prosecutors are the most powerful officials in the criminal justice system. At least ninety percent of all criminal cases are prosecuted on the state level, and in all but five jurisdictions, the chief prosecutor (also known as the district attorney) is an elected official. Most district attor- neys run unopposed and serve for decades. However, in recent years, a number of incumbent district attorneys have been challenged and defeat- ed by individuals who pledged to use their power and discretion to reduce the incarceration rate and eliminate unwarranted racial disparities in the criminal justice system. These so-called “progressive prosecutors” have enjoyed some modest successes, but many have faced challenges—from within and outside of their offices. This Article discusses some of these successes and challenges and proposes guidelines to assist newly-elected district attorneys who are committed to criminal justice reform. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................2 I. Mass Incarceration, Racial Disparities, and the Role of the Prosecutor ...............................................................................3 II. -

Beyond Non-Violent Offenses: Criminal Justice Reform and Intimate Partner Violence in the Age of Progressive Prosecution

BEYOND NON-VIOLENT OFFENSES: CRIMINAL JUSTICE REFORM AND INTIMATE PARTNER VIOLENCE IN THE AGE OF PROGRESSIVE PROSECUTION Margo Lindauer* and Emily Postman** Intimate partner violence is routinely left out of the public discourse about criminal justice reform. The criminal legal system all too often fails to effectively protect victims from intimate partner violence, although it continues to impose deleterious collateral consequences on defendants. In this Article, we review the platforms and policy agendas of four high-profile, self-identified progressive prosecutors, and discuss follow-up interviews conducted to better understand how these offices are approaching reform to traditional approaches to handling intimate partner violence cases. The reform agenda ushered in by the new wave of progressive prosecutors reflects increasing recognition of the complexities these issues raise, but has not yet translated into a clear departure from the status quo. At the same time, several concrete approaches have emerged to address longstanding issues, including increasing use of restorative justice, refusal to cooperate with immigration agencies, primary caregiver diversion programs, and renewed commitment to provide direct support to victims. No single policy will resolve the longstanding crises of domestic violence in our society, and there are still major empirical data gaps on these issues. However, as criminal justice reform movements—from progressive prosecution to abolition—gain traction, we argue that it is imperative that they squarely address domestic violence as a priority. The Article seeks to start a conversation acknowledging the reality of this crisis, mapping the limitations of existing frameworks, taking stock of emerging practices in the context of self-identified progressive prosecutors’ offices, and elevating key questions for future inquiry. -

Reimagining Prosecution: in Search of the True Progressive

American University Washington College of Law Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals Scholarship & Research 2019 Reimagining Prosecution: In Search of the True Progressive Angela J. Davis American University Washington College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/facsch_lawrev Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminal Procedure Commons Recommended Citation Reimagining Prosecution: In Search of the True Progressive, 3 UCLA Crim. Just. L. Rev. 1 (2019). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarship & Research at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles in Law Reviews & Other Academic Journals by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UCLA UCLA Criminal Justice Law Review Title Reimagining Prosecution: A Growing Progressive Movement Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2rq8t137 Journal UCLA Criminal Justice Law Review, 3(1) Author Davis, Angela J. Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California REIMAGINING PROSECUTION: A Growing Progressive Movement Angela J. Davis About the Author Angela J. Davis is a Professor at American University Washington College of Law and a former director of the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia. She thanks Meagan Allen and Philip Green for their research assistance. Abstract Prosecutors are the most powerful officials in the criminal justice system. At least ninety percent of all criminal cases are prosecuted on the state level, and in all but five jurisdictions, the chief prosecutor (also known as the district attorney) is an elected official. -

Reimagining Prosecution: a Growing Progressive Movement

UCLA UCLA Criminal Justice Law Review Title Reimagining Prosecution: A Growing Progressive Movement Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2rq8t137 Journal UCLA Criminal Justice Law Review, 3(1) Author Davis, Angela J. Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California REIMAGINING PROSECUTION: A Growing Progressive Movement Angela J. Davis About the Author Angela J. Davis is a Professor at American University Washington College of Law and a former director of the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia. She thanks Meagan Allen and Philip Green for their research assistance. Abstract Prosecutors are the most powerful officials in the criminal justice system. At least ninety percent of all criminal cases are prosecuted on the state level, and in all but five jurisdictions, the chief prosecutor (also known as the district attorney) is an elected official. Most district attor- neys run unopposed and serve for decades. However, in recent years, a number of incumbent district attorneys have been challenged and defeat- ed by individuals who pledged to use their power and discretion to reduce the incarceration rate and eliminate unwarranted racial disparities in the criminal justice system. These so-called “progressive prosecutors” have enjoyed some modest successes, but many have faced challenges—from within and outside of their offices. This Article discusses some of these successes and challenges and proposes guidelines to assist newly-elected district attorneys who are committed to criminal justice reform. Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................2 I. Mass Incarceration, Racial Disparities, and the Role of the Prosecutor ...............................................................................3 II. The Election of Progressive Prosecutors .....................................6 A. -

The Hard Truths of Progressive Prosecution and a Path to Realizing the Movement’S Promise

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 64 Issue 1 Restorative Justice: Changing the Lens Article 3 January 2020 The Hard Truths of Progressive Prosecution and a Path to Realizing the Movement’s Promise Seema Gajwani New York University School of Law Max G. Lesser Georgetown University Law Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Courts Commons, and the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Seema Gajwani & Max G. Lesser, The Hard Truths of Progressive Prosecution and a Path to Realizing the Movement’s Promise, 64 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. 70 (2019-2020). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NEW YORK LAW SCHOOL LAW REVIEW VOLUME 64 | 2019/20 VOLUME 64 | 2019/20 SEEMA GAJWANI AND MAX G. LESSER The Hard Truths of Progressive Prosecution and a Path to Realizing the Movement’s Promise 64 N.Y.L. Sch. L. Rev. 69 (2019–2020) ABOUT THE AUTHORS: Seema Gajwani, J.D. New York University School of Law; B.A. Northwestern University, has worked at the Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia as Special Counsel for Juvenile Justice Reform since 2015. There, she founded and runs the in-house restorative justice program. Gajwani spent six years as a trial attorney for the Public Defender Service for the District of Columbia and then ran the Criminal Justice Program for the Public Welfare Foundation for another eight years. -

Suffolk County District Attorney's Office District Attorney Rachael Rollins

SUFFOLK COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY'S OFFICE DISTRICT ATTORNEY RACHAEL ROLLINS The Honorable Charlie Baker Governor of Massachusetts Massachusetts State House Office of the Governor, Room 280 Boston, MA 02133 April 29, 2020 Dear Governor Baker: On behalf of the people of Suffolk County, I write to express my gratitude for the careful and deliberate steps you and your administration have taken to protect the citizens of our Commonwealth. There is no question that with your decisive actions in procuring personal protective equipment, constructing field hospitals, and supporting our healthcare workers, you are saving lives and slowing the spread of this pandemic. I do, however, have grave concerns regarding the inadequate deployment of resources in our state's jails, houses of correction, and prisons.1 Nearly a month ago, the Supreme Judicial Court (SJC) agreed with your decision to declare a statewide emergency and implement social distancing protocols. It recognized, however, that such public health precautions were not happening in our jails and prisons. Committee for Pub. Counsel Servs. v. Chief Justice of the Trial Court, 484 Mass. 431 (2020). All respondents, including myself, were thereby ordered by the Court to take drastic measures to ensure the safety of all people in Massachusetts - those incarcerated and not. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised that individuals begin to practice physical distancing by mid-March,2 understanding that such an 1 I have already addressed my significant concerns to your Chief Legal Counsel about our veterans and the elderly housed in Soldiers Homes, Nursing Homes and Assisted-Living facilities. My office is looking into the conditions at the Soldiers Home in Chelsea and the Jack Satter House, an independent senior living community in Revere. -

Suffolk County DA Rachael Rollins Holds Chelsea

Black Cyan Magenta Yellow Chelsea’s #1 Agent team. We get the highest price for our seller’s listings. Yo Hablo Jeff Bowen 781-201-9488 Sandra Castillo 617-780-6988 Español WWW.CHELSEAREALESTATE.COM | [email protected] BOOK YOUR POST IT Chelsea record Call Your YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1890 Advertising Rep (781)485-0588 VOLUME 118, No. 16 THURSDAY, JUNE 27, 2019 35 CENTS FIESTA VERANO Major Essex Planning Board approves Street eight units on Spencer Avenue project to By Adam Swift it is just too big.” While Rancatore said the begin July 8 The Planning Board has four-story building would approved plans for an eight- be comparable to the Acadia Staff Report unit, four story condominium project, it would be bigger building at Spencer and East- than other homes and build- The Essex Street Utility and ern Avenues, despite concerns ings in the neighborhood. She Roadway Improvement Proj- from some board members said it could create a domino ect is set to start construction about traffic and the size of effect, with other developers on July 8, and will encompass the project. buying smaller homes and Essex Street from Pearl Street The project at 254 Spen- knocking them down to build to Highland Street, and High- cer Ave. will now go before higher in the area. land Street from Marginal the Zoning Board of Appeals City Council President Street to Maverick Street. (ZBA) for several variances, Damali Vidot also said she Essex Street currently has including parking relief. The liked the overall look of the utility lines that date back to developer is proposing eight project but was worried it as old as 1906.