Final Draft Report Rushmere St Andrew

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asset Information (05/06/19)

ASSET INFORMATION (05/06/19) Asset Reference UPRN Town Address Description Asset Type 100086 200004658188 Aldeburgh Fort Green Car Park, Aldeburgh, IP15 5DE Paved chargeable car park Car Park (charging car park) 100087 200004658197 Aldeburgh Car Park, King Street, Aldeburgh, IP15 5BY Two small car park areas off of King Street Car Park (charging car park) 100089 200004658205 Aldeburgh Car Park, Oakley Square, Aldeburgh, IP15 5BX Pay and display car park on Oakley Street Car Park (charging car park) 100091 010013605288 Aldeburgh Thorpe Road Car Park, Aldeburgh, IP16 4NR Gravel pay and display car park Car Park (charging car park) 100090 200004670076 Aldeburgh Slaughden Quay, Slaughden Road, Aldeburgh, IP15 5DE Gravel car park Car Park (non charging) 100203 200004658158 Aldeburgh Cemetery, Aldeburgh, IP15 5DY Cemetery with path running down the middle of the land Cemetery 100205 010009906771 Aldeburgh Aldeburgh Cemetery, Victoria Road, Aldeburgh Brick built storage shed Cemetery 100292-01 010013605301 Aldeburgh Foreshore Huts Site, part of Foreshore north Crag Path, Aldeburgh Several fish huts located on the Aldeburgh beach Fishing Hut 100292-02 010013605304 Aldeburgh Foreshore on South Slaughden Road, Aldeburgh part land and foreshore South Slaughden Road Foreshore 100292-03 010013605303 Aldeburgh Part land and foreshore North Slaughden Road, Aldeburgh, IP15 5DE part land and foreshore, north Slaughden Road Foreshore 100292-04 010013605302 Aldeburgh Foreshore south of Cragg Path, Aldeburgh Foreshore located south of Cragg Path Foreshore -

Bus Services Operating Through Rushmere St Andrew

Bus Services operating through Rushmere St Andrew Route 4 Ipswich to Bixley Farm via Felixstowe Road & Broke Hall Operated by Ipswich Buses (Tel 0800 919390) Web: www.ipswichbuses.co.uk Buses run Mondays to Saturdays (except public holidays), in the daytime - approximately every half hour. Route: Ipswich Tower Ramparts - Ipswich Old Cattle Market Bus Station – Felixstowe Road – Broke Hall –Bixley Farm (via Foxhall Road, Broadlands Way, District Centre & Bixley Drive). Click here for timetable details. Timetable history:- 01/11/15 Route and timetable changes 11/04/16 Timetable changes 04/09/16 Minor timetable change 18/02/18 Timetable changes, route no longer serves Ipswich Railway station or Martlesham Heath Route 63 Ipswich to Framlingham via Woodbridge Road, Kesgrave, Martlesham, Woodbridge, Wickham Market & Hacheston Operated by First In Norfolk & Suffolk (Tel 01473 253800) Web: www.firstgroup.com/ukbus/suffolk_norfolk One school days journey each way. Route: Ipswich Old Cattle Market Bus Station – Woodbridge Road - Kesgrave (Main Road) – Fentons Way (4 services only) – Cambridge Road / Edmonton Close (3 services only) Martlesham Tesco - Woodbridge – Melton Chapel – Ufford – Wickham Market – Hacheston – Framlingham (Thomas Mills) All services are wheelchair and buggy-accessible. Click here for timetable details. Timetable history:- 30/08/15 Timetable changes 03/01/16 Timetable changes 27/03/16 Timetable changes 02/07/17 Extended route, now school days only – otherwise remainder within 64 service. Route 64 Ipswich to Aldeburgh via Woodbridge Road, Woodbridge, Melton, Saxmundham & Leiston Operated by First In Norfolk & Suffolk (Tel 01473 253800) Web: www.firstgroup.com/ukbus/suffolk_norfolk Buses run Mondays to Saturdays (except public holidays), in the daytime and early evening – typically every hour. -

1. Parish: Rushmere St Andrews

1. Parish: Rushmere St Andrews Meaning: Rushy Lake (Ekwall) 2. Hundred: Carlford Deanery: Carlford (-1920), Ipswich (1920-) Union: Woodbridge, part of Ipswich Borough RDC/UDC: (E. Suffolk) Woodbridge RD (1894-1934), Deben (1934- 1974) Suffolk Costal DC (1974-) Other administrative details: Created civil parish from part of Rushmere not within Ipswich (18%) Civil boundary change (1894) Part transferred to Ipswich (1934) Ecclesiastical boundary change to create Ipswich St Augustine of Hippo (1928) Ecclesiastical boundary change to create Ipswich St Andrew (1958) Woodbridge Petty Sessional Division Ipswich County Court District 3. Area: 1,523 acres (1912) 4. Soils: Mixed: a) Deep well drained sandy often ferruginous soils, risk wind and water erosion b) Deep fine loam soils with slowly permeable subsoils and slight seasonal waterlogging. Some fine loam over clay. Some deep well drained coarse loam over clay, fine loam and sandy soils c) Deep well drained fine loam over clay, coarse loam over clay and fine loams some with olacareous subsoils. 5. Types of farming: 1086 17 ½ acres meadow 1500–1640 Thirsk: Wood-pasture region, mainly pasture, meadow, engaged in rearing and dairying with some pig-keeping, horse breeding and poultry. Crops mainly barley with some wheat, rye, oats, peas, vetches, hops and occasionally hemp. Also has similarities with sheep-corn region where sheep are main fertilizing agent, bred for fattening barley main cash crop. 1 1818 Marshall: Wide variations of crop and management techniques including summer fallow in preparation for corn and rotation of turnip, barley, clover, weat on lighter land. 1937 Main crops: Wheat, barley, beans, peas 1969 Trist: More intensive cereal growing and sugar beet 6. -

The Parishes of Brandeston and Kettleburgh

THE PARISHES OF BRANDESTON AND KETTLEBURGH Dear Friends “Thank you”. I’ve found myself wanting to say thank you at various moments and to various people during the last month or so. I’ve wanted to say thank you to everyone who made our Harvest Festivals such memorable events earlier this month, and to all those people whose donations will provide positive improvements to the lives of people in the third World; and thank you, too, for the wonderful Harvest Lunches and Suppers which so many of us enjoyed. Thank you, also, to all who helped with the annual clean-up and tidy of Churches and Church-yards in the benefice. The spirit with which so many people took part made these occasions fun as well as achieving their purpose. And thank you, too, for all the help that you have given to your Church throughout the last year. The Church is there for you when you need it; and it is wonderful that so many people have continued to support their Church this year, in all the ways they have. Of course, November is the month each year when we express our eternal thankfulness for all those who served their country during time of war; we do this in our annual “Remembrance” of those who have lost their lives. A few weeks ago, I met a Journalist who spent six months of 2008 in Afghanistan, working with 16 th Air Assault Brigade, the Army Formation based in Colchester. He has now published a book describing the conditions under which our young men and women serve there. -

The Mattin Family of Campsea Ashe

The Mattin Family of Campsea Ashe Research by Sheila Holmes July 2014 © Sheila Holmes Mattin Family The Mattin families lived in Campsea Ashe from at least 1803 until the early part of the 20th century. Thomas Mattin and his wife Elizabeth nee Curtis, lived in the neighbouring village of Hacheston. Their son Thomas, married a girl from Campsea Ashe, where they settled for the rest of their married lives. They brought up their children and some of whom continued to live in the village. The Mattin family, were connected to several other Campsea Ashe families through marriage, such as the Youngmans , Mays, Lings, Curtis’s, Townrows and Knights. It is possible that one branch of the family lived in Little Glemham but so far no definite connection has been found, In 1881, there were there were 6 Mattin families living in the village at same time. Connection with the Youngman family. John Youngman, born 15th December 1791 and died on 15th March 1874, Campsea Ashe, married Elizabeth Ling on 25th May 1813. Their daughter, Charlotte, born 1817, married Charles Mattin,. Charles and Charlotte had a son, Charles, born 1839. Young Charles Mattin lived with his grand parents, John and Elizabeth Youngman from the age of 2 in Campsea Ashe. Charged with Actual Bodily Harm. An entry in the records of the Quarter Sessions at Ipswich on 1st July 1870 states, Charles Mattin and James Mattin, the younger, were charged with causing actual bodily harm, were sentenced to 12 calendar months imprisonment with hard labour. It is not known who these two men were or indeed whether they were members of our Mattin family. -

Fynn - Lark Ews May 2019

Fynn - Lark ews May 2019 HIGHWAYS AND BYWAYS May is traditionally a month to enjoy the great outdoors in mild and fragrant weather. Whether that means looking for a romantic maypole to dance around, trying to stay ahead of the rapid garden growth or merely enjoying the longer days and busy birdsong, it is for some a month to get outside and appreciate the English countryside we have access to, right on our doorsteps. This year sees the 70th anniversary of the creation of our National Parks – not that we have one in easy reach in Suffolk – but the same legislation required all English Parish Councils to survey all their footpaths, bridleways and byways, as the start of the legal process to record where the public had a right of way over the countryside. Magazine for the Parishes of Great & Little Bealings, Playford and Culpho 1 2 On the Little Bealings Parish Council surveyor is the rather confusing: "A website are the survey sheets showing common law right to plough exists if the the Council carrying out this duty in 1951. landowner can show, or you know, that From the descriptions of where they he has ploughed this particular stretch of walked, many of the routes are easily path for living memory. Just because a identifiable, as the routes in use are path is ploughed out does not necessarily signed ‘Public Footpath’ today. The indicate a common law right to plough; Council was required to state the reason the ploughing may be unlawful. why it thought each route it surveyed was Alternatively, there may be a right to for the public to use. -

Great Bealings Neighbourhood Plan ‘A Village in a Landscape’

Great Bealings Neighbourhood Plan ‘A Village in a Landscape’ Mission Statement Our aim is to maintain and enhance the special character of our small village within its natural setting while ensuring that the community who has chosen to live here can control, shape and contribute to how it evolves for the benefit of themselves, future residents and subsequent generations. Contents Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. HISTORICAL CONTEXT 6 3. STRATEGY AND APPROACH 11 4. NATURAL ENVIRONMENT 16 5. BUILT ENVIRONMENT 31 6. OTHER MATTERS 39 7. REFERENCES – accessed 1 September 2015 41 Appendices 1. Maps 2. Listed Buildings 3. Non Designated Heritage Assets 4. SCDC Guidance on design criteria and materials 5. Community Engagement Strategy 6. Neighbourhood Plan Questionnaire Responses 7. NPPF Guidance re. Neighbourhood Planning 8. Housing Needs Survey 9. Landscape and Wildlife Evaluation Supporting documents Where not included in this full printed version of the Plan, these are published on the website, www.gbnp.co.uk, with kind permission, and available from their respective publishing bodies: Great Bealings Neighbourhood Plan: Landscape and Wildlife Evaluation, published by Simone Bullion, Suffolk Wildlife Trust Suffolk’s Nature Strategy, published by Suffolk County Council Great Bealings Neighbourhood Plan Questionnaire, published by Great Bealings Parish Council Housing Needs Survey, published by Community Action Suffolk The Plan as a whole is published by Great Bealings Parish Council, March 2016 Cover photo by Gary Farmer – thanks also to the many contributors Submission Version 19.00, 8 March 2016 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. In April 2009 the parishes of Great Bealings, Little Bealings, and Playford worked together to produce a Parish Plan. -

Grundisburgh & Culpho Parish Council Minutes of the Annual

Grundisburgh & Culpho Parish Council Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the Council held on Monday 14th May, 2018 in the Parish Rooms, Grundisburgh. NOTICES had been posted according with regulations. Present: - Messrs.G.Caryer, S.Barnett, J.Dunnett, D.Higgins, P.Kendall, J.Lapsley, R.Youngman, Mrs.M.Bean, Mrs.J.Bignell, Mrs.S.Grahn, Mrs.A.Willetts District Councillor A.Fryatt, County Councillor R.Vickery and 12 members of the public. Before taking the chair for the Election of a Chairman Mrs.Willetts, Vice Chair, announced that Vanessa Barker had resigned from the Council on the 25th April. The District Council were notified. A by-election will be held to fill the vacancy if ten electors for the parish give notice in writing by the 21st May, 2018 claiming such an election. If no such notice is given the Parish Council will fill the vacancy by co-option. Posters have been placed in the Parish Notice Boards and posted on the What’s on in Grundisburgh News Group. Mrs.Willetts went on to say that at the beginning of the council’s new year could she remind all councillors of the need to be respectful-: respectful of each other and each other’s opinions and the right they have to hold differing opinions. Vanessa, our youngest councillor, resigned because of the aggressive behaviour at the Annual Parish Meeting on the 24th April, but this was the final straw for her after sitting through several council meetings where bullying tactics had taken place. Mrs.Willetts appealed no more point scoring please and for councillors to pull together, so the Villages can be the winner. -

Rushmere St Andrew, Ipswich

RUSHMER E S T ANDR EW, IPSWI CH CHOOSE FROM OF THE MOST LUXURIOUS HOMES IN THE HEART OF 10RURAL SUFFOLK An enviable mix of location, quality and style, a Rose home is luxury redefined – a truly enviable place to live. With just 5, five bedroom homes and 5 four bedroom homes this is a rare opportunity to own a signature property from Rose that boasts indulgent luxury. Just 7* minutes from Ipswich town centre, with its eclectic mix of independent and high street shops, and a host of places to eat, as well as being just a short drive from the coast, this is truly a premium location. *All times and distances are an approximation only. N W E S SITE 8 PLAN 5 6 7 Each of the 10 properties at Eaton Place is perfectly proportioned and truly make the most of their stunning 9 setting on the edge of the Suffolk countryside, with an abundance of surrounding space. Each property combines 4 a perfect blend of style and functionality, making Eaton Place the ideal location for your new home. 3 2 10 1 Whilst this development plan has been prepared with all due care for the convenience of the intending purchaser, the information contained herein is a preliminary guide only. Ground levels and other variances have not been shown. THE APPROACH SETS THE STANDARD FOR THE NEW HOMES; A SOLID, PANELLED, BESPOKE ‘BRICK’ WALLED ENTRANCE CREATES A SENSE OF SECURITY AND EXCLUSIVITY, THAT YOU HAVE ARRIVED... AT EATON PLACE. The homes are individually designed to an exacting detail, in a traditional format yet meeting the demand for modern WHITE contemporary layouts. -

Whats on CD Versus Files & Fiche

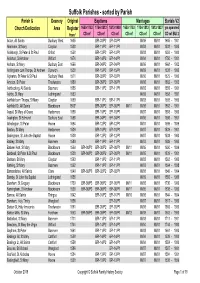

Suffolk Parishes - sorted by Parish Parish & Deanery Original Baptisms Marriages Burials V2 Church Dedication Area Register 1650-1753 1754-1812 1813-1900 1650-1753 1754-1812 1813-1837 yrs spanned from * CD ref CD ref CD ref CD ref CD ref CD ref CD ref BUI 2 Acton, All Saints Sudbury West 1605 BPI-03/P2 BPI-03/P1 MI/06 MI/01 1605 - 1901 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1538 BPI-11/P2 BPI-11/P1 MI/03 MI/01 1538 - 1900 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1558 BPI-13/P2 BPI-13/P1 MI/03 MI/01 1558 - 1900 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1674 BPI-14/P2 BPI-14/P1 MI/04 MI/01 1750 - 1901 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury East 1666 BPI-04/P2 BPI-04/P1 MI/06 MI/01 1668 - 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1538 BPI-15/P2 BPI-15/P1 MI/09 MI/01 1538 - 1900 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury West 1571 BPI-03/P2 BPI-03/P1 MI/06 MI/01 1575 - 1900 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1559 BPI-05/P2 BPI-05/P1 MI/05 MI/01 1562 - 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1555 BPI-11/P2 BPI-11/P1 MI/03 MI/01 1555 - 1901 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1553 MI/09 MI/01 1558 - 1897 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1693 BPI-11/P2 BPI-11/P1 MI/03 MI/01 1693 - 1900 Ashfield Gt, All Saints Blackbourn 1563* BPI-08/P2 BPI-08/P1 MI/11 MI/05 MI/01 1563 - 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1558 BPI-10/P2 BPI-10/P1 MI/07 MI/01 1558 - 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury East 1598 BPI-04/P2 BPI-04/P1 MI/06 MI/01 1598 - 1901 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1694 BPI-12/P2 BPI-12/P1 MI/07 MI/01 1699 - 1899 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1539 BPI-10/P2 BPI-10/P1 MI/07 MI/01 1539 - 1901 Badingham, St John -

Babergh District Council Work Completed Since April

WORK COMPLETED SINCE APRIL 2015 BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL Exchange Area Locality Served Total Postcodes Fibre Origin Suffolk Electoral SCC Councillor MP Premises Served Division Bildeston Chelsworth Rd Area, Bildeston 336 IP7 7 Ipswich Cosford Jenny Antill James Cartlidge Boxford Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 185 CO10 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Bures Church Area, Bures 349 CO8 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Clare Stoke Road Area 202 CO10 8 Haverhill Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Glemsford Cavendish 300 CO10 8 Sudbury Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Hadleigh Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 255 IP7 5 Ipswich Hadleigh Brian Riley James Cartlidge Hadleigh Brett Mill Area, Hadleigh 195 IP7 5 Ipswich Samford Gordon Jones James Cartlidge Hartest Lawshall 291 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hartest Hartest 148 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hintlesham Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 136 IP8 3 Ipswich Belstead Brook David Busby James Cartlidge Nayland High Road Area, Nayland 228 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Maple Way Area, Nayland 151 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Church St Area, Nayland Road 408 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Bear St Area, Nayland 201 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 271 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Shotley Shotley Gate 201 IP9 1 Ipswich -

Suffolk Coastal District Local Plan Core Strategy & Development Management Policies

Suffolk Coastal... ...where quality of life counts Suffolk Coastal District Local Plan Core Strategy & Development Management Policies Development Plan Document July 2013 Cover IMage CreDIt: - scdc Foreword this document, the Core Strategy of the Suffolk Coastal District Local Plan, is the first and central part of our new Local Plan which will guide development across the District until 2027 and beyond. Suffolk Coastal District is a uniquely attractive place to live and work, combining a strong economy with a natural and built environment second to none. those advantages however present us with the challenge of so guiding development that we continue to stimulate and support that economy, we provide attractive and affordable homes for current and future generations, and we achieve all that in a way which preserves and enhances that precious, but sometimes vulnerable, environment. the Core Strategy sets out a vision for the District as we go forward over the next 15 years. objectives derived from that vision, and the Strategic Policies designed to achieve those, do so in a way which recognises and builds on the diversity of the different communities which together make our District the wonderful place it is. they reflect both the opportunities and threats which that diversity brings with it. the Development Management Policies then set out in more detail specific approaches for different aspects or types of development to ensure that each contributes in a consistent way to those objectives and strategies. alongside these clear local aspirations, the Strategy has developed, evolved and been refined over a decade to ensure that it meets both its international obligations in terms of areas designated for their high quality nature conservation interest, and the contribution it can make to the wider sub-national and national economy, within continuously evolving national planning policies for our society as a whole.