Collection Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marsh Creek State Park

John Marsh Historic Trust presents STONE HOUSE HERITAGE DAY Marsh Creek State Park 21789 Marsh Creek Road @ Vintage Parkway th Saturday, October 17 10 am – 4 pm Get an up-close look, inside and out, at Marsh’s 159-year-old mansion The John Marsh Story Scheduled Presentations Hear the story of the remarkable life of John Marsh, pioneer who blazed a trail across 10:00 Opening Welcome America and was the first American to settle in 11:00 Presenting Dr. John Marsh Contra Costa County. 11:00 Guided hike begins GUIDED HIKE ($5 donation suggested) Enjoy an easy, guided hike through 3 miles of 11:30 Stone House history Marsh Creek State Park. 12:00 Ancient archaeology of MCSP Archaeological Discoveries 12:00-1:30 Brentwood Concert Band View important archeological finds dating 12:30 Marsh Creek State Park plans 7,000 to 3,000 years old, including items associated with an ancient village. 1:30 Professional ropers/Vaqueros Native American Life 2:30 Presenting Dr. John Marsh See members of the Ohlone tribe making brushes, rope, jewelry and acorn meal. Enjoy Kids’ Activities All Day Rancho Los Meganos Experience the work of the Vaquero, who Rope a worked John Marsh’s rancho. ‘steer’ Period Music Hear music presented by the Brentwood Concert Band. Take a ‘Pioneer family’ Westward Movement picture how Marsh triggered the pre-Gold Rush Learn migration to California, which established the historic California Trail. Co-hosted by Support preservation of the John Marsh House with your tax deductible contribution today at www.johnmarshhouse.com at www.razoo.com/john -marsh-historic-trust, or by check to Sponsored by John Marsh Historic Trust, P.O. -

Minnesota Mississippi River Parkway Commission 1St Quarter Meeting February 28, 2013 2:30 – 5:00 P.M

Minnesota Mississippi River Parkway Commission 1st Quarter Meeting February 28, 2013 2:30 – 5:00 p.m. State Office Building Room 400 North DRAFT AGENDA ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ 2:30 p.m. Welcome & Introductions S. Johnson 2:35 p.m. Approve Today’s Agenda & Minutes from 11/29/12 S. Johnson/All 2:40 p.m. Commission Business - FY ‘13 Budget Status Anderson/Miller - Legislative Session Updates House/Senate Members 2:55 p.m. National MRPC Updates - MRPC Board S. Johnson - 2013 Semi-Annual Meeting, Apr 25-27, Bettendorf, IA All - MPRC Committee Updates Committee Members - GRR 75th Anniversary – Great Race, June 20-22 3:15 p.m. Old Business – Updates - Corridor Management Plan Project Zoff/Miller - Visual Resource Protection Plan Zoff/Miller - Silica Sand Mining S. Johnson/Zoff - CapX 2020 Mulry - MN GRR Map Reprint Miller 4:00 p.m. New Business - Great River Gathering, May 9 – Exhibit Booth & Dinner All - Miller Black Bear Area Trail Schaubach/Samp - GRR Hospitality Training Wheeler/Zoff/Miller 4:20 p.m. Agency and Regional Updates - Lake Itasca to Grand Rapids Lucachick - Grand Rapids to Brainerd Schaubach - Brainerd to Elk River Samp - Elk River to Hastings Pierson - Hastings to Iowa Border Mulry - Agriculture Hugunin - Explore MN Tourism A. Johnson/Offerman - Historical Society Kajer/Kelliher - Natural Resources Parker/Wheeler - Transportation Bradley/Zoff - National Park Service/MISS Labovitz 4:55 p.m. Recognition of Service to the MN-MRPC – Frank Pafko All 5:00 p.m. Wrap Up and Adjourn 1 Minnesota Mississippi River Parkway Commission 4th Quarter Meeting – November 29, 2012 State Office Building, St. Paul MN MINUTES - Draft Diane Henry-Wangensteen - LCC Commissioners Present Chris Miller - Staff Rep. -

Cultural Imagery's Changing Place in Athletics

University of South Dakota USD RED Honors Thesis Theses, Dissertations, and Student Projects Spring 2018 Cultural Imagery’s Changing Place in Athletics Cash Anderson University of South Dakota Follow this and additional works at: https://red.library.usd.edu/honors-thesis Recommended Citation Anderson, Cash, "Cultural Imagery’s Changing Place in Athletics" (2018). Honors Thesis. 6. https://red.library.usd.edu/honors-thesis/6 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Student Projects at USD RED. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Thesis by an authorized administrator of USD RED. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cultural Imagery’s Changing Place in Athletics by Cash Anderson A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the University Honors Program Department of Political Science The University of South Dakota May 2018 The members of the Honors Thesis Committee appointed to examine the thesis of Cash Anderson find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ____________________________________ Mr. Marshall Damgaard Adjunct Instructor of Political Science Director of the Committee ____________________________________ Mr. Gary Larson Lecturer of Media and Journalism ____________________________________ Dr. Scott Breuninger Associate Professor of History ABSTRACT Cultural Imagery’s Changing Place in Athletics Cash Anderson Director: Marshall Damgaard Every sports team is represented by its name, mascot, and logo. For many, the representative of their team is an historical people. Recent pushes for social justice have started questioning nicknames and mascots, leading to many getting changed. In 2005, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) enacted a policy that prohibited universities with hostile or abusive nicknames from postseason participation. -

Appomattox Statue Other Names/Site Number: DHR No

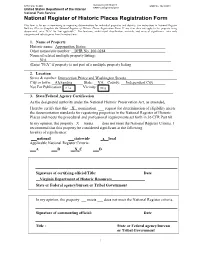

NPS Form 10-900 VLR Listing 03/16/2017 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior NRHP Listing 06/12/2017 National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. 1. Name of Property Historic name: Appomattox Statue Other names/site number: DHR No. 100-0284 Name of related multiple property listing: N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing ____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Location Street & number: Intersection Prince and Washington Streets City or town: Alexandria State: VA County: Independent City Not For Publication: N/A Vicinity: N/A ____________________________________________________________________________ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination ___ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements -

Download Catalog

Abraham Lincoln Book Shop, Inc. Catalog 183 Holiday/Winter 2020 HANDSOME BOOKS IN LEATHER GOOD HISTORY -- IDEAL AS HOLIDAY GIFTS FOR YOURSELF OR OTHERS A. Badeau, Adam. MILITARY HISTORY OF ULYSSES S. GRANT, FROM APRIL 1861 TO APRIL 1865. New York: 1881. 2nd ed.; 3 vol., illus., all maps. Later full leather; gilt titled and decorated spines; marbled endsheets. The military secretary of the Union commander tells the story of his chief; a detailed, sympathetic account. Excellent; handsome. $875.00 B. Beveridge, Albert J. ABRAHAM LINCOLN 1809-1858. Boston: 1928. 4 vols. 1st trade edition in the Publisher’s Presentation Binding of ½-tan leather w/ sp. labels; deckled edges. This work is the classic history of Lincoln’s Illinois years -- and still, perhaps, the finest. Excellent; lt. rub. only. Set of Illinois Governor Otto Kerner with his library “name” stamp in each volume. $750.00 C. Draper, William L., editor. GREAT AMERICAN LAWYERS: THE LIVES AND INFLUENCE OF JUDGES AND LAWYERS WHO HAVE ACQUIRED PERMANENT NATIONAL REPUTATION AND HAVE DEVELOPED THE JURISPRUDENCE OF THE UNITED STATES. Phila.: John Winston Co.,1907. #497/500 sets. 8 volumes; ¾-morocco; marbled boards/endsheets; raised bands; leather spine labels; gilt top edges; frontis.; illus. Marshall, Jay, Hamilton, Taney, Kent, Lincoln, Evarts, Patrick Henry, and a host of others have individual chapters written about them by prominent legal minds of the day. A handsome set that any lawyer would enjoy having on his/her shelf. Excellent. $325.00 D. Freeman, Douglas Southall. R. E. LEE: A BIOGRAPHY. New York, 1936. “Pulitzer Prize Edition” 4 vols., fts., illus., maps. -

Photographs from the Marsh Family Papers, Circa 1855-1952

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf3k40033b Online items available Inventory of Photographs from the Marsh Family Papers, circa 1855-1952 Processed by The Bancroft Library staff The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Inventory of Photographs from BANC PIC 1963.004-.009 1 the Marsh Family Papers, circa 1855-1952 Inventory of Photographs from the Marsh Family Papers, circa 1855-1952 Collection number: BANC PIC 1963.004-.009 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Finding Aid Author(s): Processed by The Bancroft Library staff Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX © 2016 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Photographs from the Marsh Family papers Date (inclusive): circa 1855-1952 Collection Number: BANC PIC 1963.004-.009 Creator: Marsh family Extent: circa 350 photographic prints91 digital objects (91 images) Repository: The Bancroft Library. University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ Abstract: Photographs from the Marsh and Camron (Cameron) family. Collection includes large number of portraits and several albums of the Marsh and Camron (Cameron) families and friends. In addition, views taken in San Francisco, Santa Barbara, Monterey, Mill Valley, Pleasanton, Auburn, Ben Lomond, Soda Spring, Calif. -

John Marsh's Stone House Alice Was Four Years Old, Abby Had Granted the Four-League Died of Tuberculosis in August ,~ " .,'( Hood

10 THE INDEPENDENT • THURSDAY, JANUARY 12, 2012 Community Do You In December 1837 John A tower added a fourth floor. The Marsh bought Los Meganos, a Remember? building has 7,000 square feet. rancho north of Robert Liver There was a veranda on three more's Rancho Las Positas, from By Anne Homan sides of the first floor, and the its original grantee, Jose Noriega, veranda's roof was accessible for $500. Alta California's from the second floor. When Mexican Governor Jose Castro John Marsh's Stone House Alice was four years old, Abby had granted the four-league died of tuberculosis in August ,~ " .,'( hood. When gold was discovered (about 20,846 acres) rancho to 218 pounds, stood six feet two, .... 1855. In early September 1856 ~.\.';(-.:.--. - ~ and was bronzed and powerfully , ,t. ~ . ,.. "" in California, Marsh traveled to Noriega in 1835. Marsh's rancho 1fl!: ••","I':"" .,.. ,';"1 Marsh moved his belongings into included part of the Arroyo de built. .\.r. ~ '. 'J : 1, ..;,\ Park's Bar, north of Marysville, the new house. Two weeks later, ." J. " ,: ~ ' ..... , P, where he struck it rich. He had los Poblados (now Marsh Creek) Marsh was now the only " -. '- ~ 'J. .,1 ':6'i,., Marsh was stabbed to death by medical doctor in California. " .~'I"" .~. :"!~ also brought goods with him to watershed, and Marsh could not ~ ';.... ~ ~~ three vaqueros who stopped his His biographer, George Lyman, I '.' • ~I trade for gold from other min take possession of his land until \"~ - " #: buggy and robbed him when he suggested that he use a deserted . 'rl''i . ers. In only a few months, he late April 1838 because of heavy 1".,.'.,\, ..... -

The Civil War & the Northern Plains: a Sesquicentennial Observance

Papers of the Forty-Third Annual DAKOTA CONFERENCE A National Conference on the Northern Plains “The Civil War & The Northern Plains: A Sesquicentennial Observance” Augustana College Sioux Falls, South Dakota April 29-30, 2011 Complied by Kristi Thomas and Harry F. Thompson Major funding for the Forty-Third Annual Dakota Conference was provided by Loren and Mavis Amundson CWS Endowment/SFACF, Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission, Tony and Anne Haga, Carol Rae Hansen, Andrew Gilmour and Grace Hansen-Gilmour, Carol M. Mashek, Elaine Nelson McIntosh, Mellon Fund Committee of Augustana College, Rex Myers and Susan Richards, Rollyn H. Samp in Honor of Ardyce Samp, Roger and Shirley Schuller in Honor of Matthew Schuller, Jerry and Gail Simmons, Robert and Sharon Steensma, Blair and Linda Tremere, Richard and Michelle Van Demark, Jamie and Penny Volin, and the Center for Western Studies. The Center for Western Studies Augustana College 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ........................................................................................................................................................... v Anderberg, Kat Sailing Across a Sea of Grass: Ecological Restoration and Conservation on the Great Plains ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Anderson, Grant Sons of Dixie Defend Dakota .......................................................................................................... 13 Benson, Bob The -

Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context, 1837 to 1975

SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota May 2017 SAINT PAUL AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORIC AND CULTURAL CONTEXT, 1837 TO 1975 Ramsey County, Minnesota MnHPO File No. Pending 106 Group Project No. 2206 SUBMITTED TO: Aurora Saint Anthony Neighborhood Development Corporation 774 University Avenue Saint Paul, MN 55104 SUBMITTED BY: 106 Group 1295 Bandana Blvd. #335 Saint Paul, MN 55108 PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Nicole Foss, M.A. REPORT AUTHORS: Nicole Foss, M.A. Kelly Wilder, J.D. May 2016 This project has been financed in part with funds provided by the State of Minnesota from the Arts and Cultural Heritage Fund through the Minnesota Historical Society. Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context ABSTRACT Saint Paul’s African American community is long established—rooted, yet dynamic. From their beginnings, Blacks in Minnesota have had tremendous impact on the state’s economy, culture, and political development. Although there has been an African American presence in Saint Paul for more than 150 years, adequate research has not been completed to account for and protect sites with significance to the community. One of the objectives outlined in the City of Saint Paul’s 2009 Historic Preservation Plan is the development of historic contexts “for the most threatened resource types and areas,” including immigrant and ethnic communities (City of Saint Paul 2009:12). The primary objective for development of this Saint Paul African American Historic and Cultural Context Project (Context Study) was to lay a solid foundation for identification of key sites of historic significance and advancing preservation of these sites and the community’s stories. -

An Investigation Into British Neutrality During the American Civil War 1861-65

AN INVESTIGATION INTO BRITISH NEUTRALITY DURING THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR 1861-65 BY REBECCA CHRISTINE ROBERTS-GAWEN A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of MA by Research Department of History University of Birmingham November 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis sought to investigate why the British retained their policy of neutrality throughout the American Civil War, 1861-65, and whether the lack of intervention suggested British apathy towards the conflict. It discovered that British intervention was possible in a number of instances, such as the Trent Affair of 1861, but deliberately obstructed Federal diplomacy, such as the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. This thesis suggests that the British public lacked substantial and sustained support for intervention. Some studies have suggested that the Union Blockade of Southern ports may have tempted British intervention. This thesis demonstrates how the British sought and implemented replacement cotton to support the British textile industry. This study also demonstrates that, by the outbreak of the Civil War, British society lacked substantial support for foreign abolitionists’’ campaigns, thus making American slavery a poorly supported reason for intervention. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1995, Volume 90, Issue No. 4

I-1-Si Winter 1995 MARYLAND 2 -aa> 3 Q. Historical Magazine THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY Founded 1844 Dennis A. Fiori, Director The Maryland Historical Magazine Ernest L. Scott Jr., Editor Robert I. Cottom Jr., Associate Editor Patricia Dockman Anderson, Associate Editor Jessica M. Pigza, Managing Editor Jeff Goldman, Photographer Angela Anthony, Robin Donaldson Coblentz, Christopher T.George, Jane Gushing Lange, and Lama S. Rice, Editorial Associates Robert J. Brugger, Consulting Editor Regional Editors John B. Wiseman, Frostburg State University Jane G. Sween, Montgomery Gounty Historical Society Pegram Johnson III, Accoceek, Maryland John R. Wennersten, University of Maryland, Eastern Shore Acting as an editorial board, the Publications Committee of the Maryland Historical Society oversees and supports the magazine staff. Members of the committee are: Robert J. Brugger, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Go-Ghair John W. Mitchell, Upper Marlboro; Trustee, Go-Ghair Joseph L. Arnold, University of Maryland, Baltimore Gounty Jean H. Baker, Goucher Gollege James H. Bready, Baltimore Lois Green Garr, St. Mary's Gity Gommission Stiles Tuttle Golwill, Baltimore Richard R. Duncan, Georgetown University Dennis A. Fiori, Maryland Historical Society, ex-officio Jack G. Goellner, The Johns Hopkins University Press Gilbert Gude, Bethesda David Hein, Hood Gollege John Higham, The Johns Hopkins University Ronald Hoffman, Institute of Early American History and Gulture Samuel Hopkins, Baltimore Gharles McG. Mathias, Ghevy Ghase Roland G. McGonnell, Morgan State University Norvell E. Miller III, Baltimore Edward G. Papenfuse, Maryland State Archives The views and conclusions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors. The editors are responsible for the decision to make them public. -

First Battle of Bull Run-Manassas

Name: edHelper First Battle of Bull Run-Manassas The thought that the American Civil War would last four long years never entered the minds of most of the people. It was assumed by people on both sides that each side would win quickly. It is interesting to note that many of the battles during the war had two names. The North would name them after the nearest body of water-- in this case, a stream called Bull Run. (Run is an early English word that means a stream or creek.) The South named them after the nearest town, such as Manassas. The new capital for the Confederacy (Richmond, Virginia) was only 100 miles away from the Union capital (Washington, D.C.). When this great battle came, it was certain to take place between the two cities because of their proximity. In preparation for an assault, the Union soldiers began fortifying areas around the capital and the nearby towns of Alexandria and Arlington, Virginia. Confederate forces made no immediate effort to attack Washington as the Union expected them to do. Instead, General Beauregard gathered his army at Manassas Junction where there was a railway. Union forces were commanded by General Winfield Scott, but he was too old and infirm to lead the men on the field. That job fell to General Irwin McDowell. While many men had flocked to the Union banner, few had any training as soldiers. He wanted time to train the men for battle, but Congress wanted him to confront the Confederates. The two forces met near the creek called Bull Run on July 21, 1861.