Successful Places a Guide to Sustainable Housing Layout and Design For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTICE of ORDER Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 Section 53 Derbyshire County Council (Upgrading to Bridleway of Public Footpath No

NOTICE OF ORDER Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 Section 53 Derbyshire County Council (Upgrading to Bridleway of Public Footpath No. 17 (Part) and 18 – Parish of Pleasley); Modification Order 2016 Notice is hereby given that the above referenced Order has been submitted to the Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs for determination. An Inspector will be appointed by the Secretary of State to determine the Order. The start date for the above Order is 6 July 2018. Consideration of the Order will take the form of a public local inquiry. The Inquiry will be held at the New Houghton Community Centre, 13 Rotherham Road, New Houghton, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire NG19 8TE, on Wednesday 5 December 2018 at 10.00am. The effect of the Order, if confirmed without modifications, will be to modify the Definitive Map and Statement for the area by upgrading to a bridleway part of Public Footpath No. 17 in the Parish of Pleasley from a point at grid reference SK 5154 6505 and proceeding for a distance of 1143 metres or thereabouts in a generally south easterly, then north easterly, then south easterly then north easterly direction to a point at grid reference SK 5242 6511, with a width of 3.5 metres, and by upgrading to a bridleway Public Footpath No. 18 in the Parish of Pleasley from a point at grid reference SK 5242 6511 and proceeding for a distance of 57 metres or thereabouts in a generally easterly direction to a point at grid reference SK 5248 6512, with a width of 3.5 metres. -

Southwell and Nottingham

Locality Church Name Parish County Diocese Date Grant reason ALLENTON Mission Church ALVASTON Derbyshire Southwell 1925 New Church ASKHAM St. Nicholas ASKHAM Nottinghamshire Southwell 1906-1908 Enlargement ATTENBOROUGH St. Mary Magdalene ATTENBOROUGH Nottinghamshire Southwell 1948-1950 Repairs ATTENBOROUGH St. Mary Magdalene ATTENBOROUGH Nottinghamshire Southwell 1956-1957 Repairs BALDERTON St. Giles BALDERTON Nottinghamshire Southwell 1930-1931 Reseating/Repairs BAWTRY St. Nicholas BAWTRY Yorkshire Southwell 1900-1901 Reseating/Repairs BLIDWORTH St. Mary & St. Laurence BLIDWORTH Nottinghamshire Southwell 1911-1914 Reseating BLYTH St. Mary & St. Martin BLYTH Derbyshire Southwell 1930-1931 Repairs BOLSOVER St. Mary & St. Laurence BOLSOVER Derbyshire Southwell 1897-1898 Rebuild BOTHAMSALL St. Peter BOTHAMSALL Nottinghamshire Southwell 1929-1930 Repairs BREADSALL All Saints BREADSALL Derbyshire Southwell 1914-1916 Enlargement BRIDGFORD, EAST St. Peter BRIDGFORD, EAST Nottinghamshire Southwell 1901-1905 Repairs BRIDGFORD, EAST St. Peter BRIDGFORD, EAST Nottinghamshire Southwell 1913-1916 Repairs BRIDGFORD, EAST St. Peter BRIDGFORD, EAST Nottinghamshire Southwell 1964-1969 Repairs BUXTON St. Mary BUXTON Derbyshire Southwell 1914 New Church CHELLASTON St. Peter CHELLASTON Derbyshire Southwell 1926-1927 Repairs CHESTERFIELD Christ Church CHESTERFIELD, Holy Trinity Derbyshire Southwell 1912-1913 Enlargement CHESTERFIELD St. Augustine & St. Augustine CHESTERFIELD, St. Mary & All Saints Derbyshire Southwell 1915-1931 New Church CHILWELL Christ Church CHILWELL Nottinghamshire Southwell 1955-1957 Enlargement CLIPSTONE All Saints, New Clipstone EDWINSTOWE Nottinghamshire Southwell 1926-1928 New Church CRESSWELL St. Mary Magdalene CRESSWELL Derbyshire Southwell 1913-1914 Enlargement DARLEY St. Mary the Virgin, South Darley DARLEY, St. Mary the Virgin, South Darley Derbyshire Southwell 1884-1887 Enlargement DERBY St. Dunstan by the Forge DERBY, St. James the Great Derbyshire Southwell 1889 New Church DERBY St. -

The Office of Police and Crime Commissioner for Derbyshire

Section A DECISION NOTICE For Publication AUGUST 2016 THE OFFICE OF POLICE AND CRIME COMMISSIONER FOR DERBYSHIRE DECISION RECORD Received in OPCC Request for PCC Decision OPCC Ref: 33/ 16 Date: 27 June 2016 Title: COMPENSATION: BOLSOVER DISTRICT COUNCIL Executive Summary: Five years ago, the Police Authority approved Derbyshire Police to co-locate the Bolsover Section to Bolsover District Council Offices. The Council took on an obligation to provide similar facilities were they to relocate, which they did, to Clowne. Bolsover District Council has already paid Derbyshire Police a sum to relocate from their council offices to temporary accommodation and to then move into a more permanent solution at Oxcroft House. This coincided with the force’s strategic policing review so the Chief Constable and Commissioner decided that it would be inappropriate to commit to a further long lease of Oxcroft House as it may not meet the new needs of the force going forward. Considerable costs had already been incurred by Bolsover District Council in developing this scheme. Bolsover District Council have demonstrated that they have incurred costs to date (supported by documentary evidence); the Constabulary are still holding removal monies for which there is no justification. Decision Resolved that the Commissioner agrees to pay compensation to Bolsover District Council as set out within their claim and as detailed in the confidential report. Declaration 1 \\Srvsdrive01\fhq\HQ\OPCC\Governance & Strategic Planning\Strategic Governance Board\2016\Decision Log 2016\DN33 Compensation Bolsover District Council\DN Bolsover DC Decision Notice.docx DECISION NOTICE AUGUST 2016 I confirm that I have considered whether or not I have any personal or prejudicial interest in this matter and take the proposed decision in compliance with the Code of Conduct for the Police and Crime Commissioner for Derbyshire. -

3 September 18

PLEASLEY PARISH COUNCIL MINUTES OF THE PARISH COUNCIL MEETING HELD ON 3 September 2018 Present Councillor J H Wright (Chair) Councillors, I Allen, Mrs P M Bowmer, D M Gamble, D Gelsthorpe, Mrs J Jones, N Jordan Also present: None PART1 NON-CONFIDENTIAL INFORMATION 211/18 Apologies for absence Apologies for absence were noted from Mrs C Randall and T Kirkham who were on holiday, and from Councillor Mrs V Douglas who has a long-term illness. 212/18 Declaration of Members interests None 213/18 Dispensation granted to Members declaring disclosable pecuniary interests in an agenda item None 214/18 Public Participation (i) No members of the public were present. (ii) Report of the Police Representative No police representative was present at the meeting. The Clerk reported the crime statistics for May and June 2018 published on the Police website: May 2018 Anti-Social Behaviour 5 Burglary 3 Other crime 1 Vehicle Crime 1 Violence and sexual offences 1 1 June 2018 Anti-Social Behaviour 4 Burglary 1 Vehicle Crime 2 Violence and sexual offences 3 (iii) Report of the County Councillor Councillor Dale reported that she intends to follow up on a longstanding request to prune the trees which have now grown taller than the footbridge which passes over the A617, near the Bus Stops adjacent to and opposite Anthony Bek School, connecting Pleasley and New Houghton. It was also reported that trials are now taking place in Derbyshire to create stronger asphalt for road repairs using a process which involves turning waste plastic into small pellets which are then added into an asphalt mix in place of Bitumen (iv) Report of the District Councillor Mrs P M Bowmer The District Councillor reported that Bolsover District Council is currently in recess. -

August 2019 Every Sunday, Monday and Thursday at 10Am Free Walks of 4 to 6 Miles Lasting About 2 Hours, Led by Trained Volunteers, in and Around Mansfield

instep March - August 2019 Every Sunday, Monday and Thursday at 10am Free walks of 4 to 6 miles lasting about 2 hours, led by trained volunteers, in and around Mansfield. March Day Date Venue Grade Sun 3-Mar Fountaindale Moderate/Long Mon 4-Mar Hardwick Hall Strenuous Thu 7-Mar Pleasley Circular Moderate Sun 10-Mar Kirkby Parks Moderate Mon 11-Mar Oak Tree Heath Moderate Thu 14-Mar Meden Vale Moderate/Long Sun 17-Mar Burnt Stump Moderate Mon 18-Mar Felley Strenuous Thu 21-Mar Boundary Wood Moderate Sun 24-Mar Skegby Moderate Mon 25-Mar Scarcliffe Moderate Thu 28-Mar Bestwood Country Park Strenuous Sun 31-Mar Shirebrook Wood Moderate April Day Date Venue Grade Mon 1-Apr Thieves Wood Moderate Thu 4-Apr Woodhouse Trail Moderate Sun 7-Apr Farnsfield Strenuous Mon 8-Apr Teversal Trail Moderate Thu 11-Apr Annesley Moderate Sun 14-Apr Rowthorne Moderate Mon 15-Apr Birklands Moderate Thu 18-Apr King’s Mill Moderate Sun 21-Apr Easter Sunday Mon 22-Apr No Walk Thu 25-Apr Palterton Strenuous Sun 28-Apr Sherwood Forest Moderate Mon 29-Apr Sookholme Moderate/Long May Day Date Venue Grade Thu 2-May Poulter Park Moderate Sun 5-May No Walk Mon 6-May Bank Holiday Thu 9-May Fountaindale Moderate/Long Sun 12-May Hardwick Hall Strenuous Mon 13-May Pleasley Circular Moderate Thu 16-May Kirkby Dumbles Strenuous Sun 19-May Oak Tree Heath Moderate Mon 20-May Meden Vale Moderate/Long Thu 23-May Burnt Stump Moderate Sun 26-May No Walk Mon 27-May Bank Holiday Thu 30-May Skegby Moderate June Day Date Venue Grade Sun 2-Jun Scarcliffe Moderate Mon 3-Jun Bestwood Country -

Q3y Saturday 3D Septembe.R a Swadlincote Potteries Sunday 4Th

I !.r I. 7 d, 'l' r;' I AIA Conference - Derbvshire - September 2005 ; Visit Notes Q3y Visit Ref Saturday 3d Septembe.r A Swadlincote potteries B Belper Mills and Strutt housing C Heage Windmill & Morley Park lronworks Sunday 4th September D Derby Rai|ways E Long Eaton & Shardlow F Darley Abbey and Derby llills * Monday Sth September G Peak District Lead H Caudwells Mill & Hope CementWorks Tuesday 6th September J Cromford & Matlock K National Stone Centre and CHpR Wednesday 7th September L North East Derbyshire M Erewash Valley Thursday 8h September N South Derbyshire AIA 2005 Derbyshire Tour Notes Saturday 3'September Visit A Swadlincote Potteries Sharpe's Potterv Thomas Sharpe, a local farmer, started his pottery in 1821, one of half a dozen pot-banks founded at that time. He used the good clay available in South Derbyshire and made domestic ware. Colour (acid), white glaze and blue (alkali) wares were made and were soon being exported. As customary, a long central workshop was flanked by a kiln at each end, for biscuit and glaze firings respectively. There was great demand for toilet bowls and sinks in the 1850s - the flushing rim pan principle still used today was patented by E Sharpe. A new works was built in the 1850s with another pair of kilns (demolished 1 906). There was further development in 1901 across West Street, that site later passing to Burton Co-operative Society, who have since sold part of it; the curved facade of the car parts shop on the corner betrays a former kiln. Sharpe's ran a maximum of six kilns at any one time. -

Road Improvement Schemes

Road Improvement Schemes Traffic regulation orders, minor and major improvements within Derbyshire with the exception of Derby City Council, which is a unitary authority. Some roads in Derbyshire form part of the Trunk Road network and are managed by Highways England. These include the M1, A38, A628, A6, A52 and A50. Please refer to Highways England (opens in a new window) for information. District Parish Location Details Status Potential bypass listed in Local Transport Plan "for further appraisal in Amber Valley Ripley/Codnor Butterley to Ormonde Fields Ongoing association with land use plans" Contact [email protected] Amber Valley South Wingfield Linbery Close Proposed 30mph speed limit Ongoing Roundabout junction with Oxcroft Way east & west direction, Slayley View Road, High Hazels Bolsover Barlborough Proposed Traffic Regulation Order ‐ Double Yellow Lines Ongoing Road, further section of Midland Way at bends near Centenary House Due to start 27 Bolsover Blackwell Hall Lane, Alfreton Road, Cragg Lane Relocation of pedestrian refuge including tactile crossing points April Various junctions inc Victoria St,Cross Bolsover Bolsover Proposed Traffic Reguslation Order ‐ Double Yellow Lines Ongoing St,Mansfield Rd,Nesbitt St, A632 Castle Lane from High Street junction to Bolsover Bolsover Proposed Traffic Regulation Order ‐ Double Yellow Lines Ongoing include right then left hand bend Generated: 03/12/2020 District Parish Location Details Status High Street opposite junction with Cotton Bolsover Bolsover Proposed Traffic Regulation -

Minutes 2017 09 12

Minutes of the Meeting of Old Bolsover Town Council Held on Tuesday 12th September 2017 at the Town Hall, Cotton Street, Bolsover, Chesterfield Present: Councillor D. Adams Councillor T. Bagguley Councillor T. Bennett Councillor R. Bowler Councillor P. Cooper (Chair) Councillor C.P. Cooper Councillor S. Gibbons Councillor B. Haigh Councillor R. Hobson Councillor J. Rushby In attendance: Andrew Tristram -Town Clerk Councillor J. Dixon (Derbyshire County Council) Councillor Mark Dixey (Bolsover District Council) Cora Glasser (Junction Arts) PCSO Ben Perry 6 Members of the Public Presentations of three cheques for Charity Day of £150 each were made to St. John Ambulance, Badgers and Bluebell Wood. 1. Apologies for Absence Apologies were received from Councillor M. Longden and R. Tooth 2. Variation to Order of Business None 3. Declarations of Disclosable Pecuniary and Non Disclosable Pecuniary/other Interests. Councillor Paul Cooper – Planning Committee BDC 4. Junction Arts – 2017 Lantern Parade Cora Glasser attended the meeting from Junction Arts to provide some feedback on the 2016 Event and inform members of the plants for the 2017 Lantern Parade. 5. Public Speaking (a) Public Request from resident to use Bainbridge Hall for craft and art workshops. Congratulations received for the new flagpole 17 Concerns for pedestrian crossing and parking concerns near the Horsehead Lane entrance of Bolsover C of E School. Damage to grass verges caused by parking. Litter near bus shelter and cigarette ends outside Cavendish Pub. Request for greater CAN Ranger presence in Bolsover Effectiveness of parking enforcement. (b) Police Representatives PCSO Ben Perry attended the meeting and spoke to members about their request for the Council to fund the purchase of two ANPR cameras. -

53A Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

53A bus time schedule & line map 53A Mansƒeld - She∆eld View In Website Mode The 53A bus line (Mansƒeld - She∆eld) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bolsover: 11:12 PM (2) Halfway: 5:35 PM - 9:57 PM (3) Mansƒeld: 7:12 PM - 9:12 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 53A bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 53A bus arriving. Direction: Bolsover 53A bus Time Schedule 38 stops Bolsover Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 11:12 PM Eckington Way/Station Road, Halfway Eckington Way, England Tuesday 11:12 PM Rotherham Road/Station Road, Halfway Wednesday 11:12 PM Rotherham Road/School Avenue, Halfway Thursday 11:12 PM Rotherham Road, England Friday 11:12 PM Rotherham Road/Sewell Road, Halfway Saturday 11:12 PM Pipworth Lane, Eckington Rotherham Road, Eckington Civil Parish Rectory Close, Eckington 53A bus Info Direction: Bolsover Prince Of Wales, Eckington Stops: 38 Trip Duration: 49 min Bus Station, Eckington Line Summary: Eckington Way/Station Road, Pinfold Street, Eckington Halfway, Rotherham Road/Station Road, Halfway, Rotherham Road/School Avenue, Halfway, Station Road, Eckington Rotherham Road/Sewell Road, Halfway, Pipworth Lane, Eckington, Rectory Close, Eckington, Prince Of Golf Club, Renishaw Wales, Eckington, Bus Station, Eckington, Station Road, Eckington, Golf Club, Renishaw, Hague Lane Hague Lane Main Road, Renishaw Main Road, Renishaw, Church, Renishaw, Community Hall, Renishaw, Blacksmiths Arms, Church, Renishaw Renishaw, War Memorial, Barlborough, De -

53 53A Valid From: 05 July 2020

Bus service(s) 53 53a Valid from: 05 July 2020 Areas served Places on the route Sheffield (53) Sheffield Interchange Mosborough (53) Sheffield Rail Station Halfway (53a) Halfway Tram Terminus (53a) Eckington Renishaw Hall Renishaw Barlborough Clowne Bolsover Pleasley Mansfield What’s changed From Sunday 5 July there will be changes to the timetable. Operator(s) How can I get more information? TravelSouthYorkshire @TSYalerts 01709 51 51 51 Bus route map for services 53 and 53a 12/05/2015 Sheeld,Atterclie Interchange 53 Ulley Manor Top, City Rd/Elm Tree Sheeld, Fence Sheaf Street/ Aston Todwick Sheeld Station Woodhouse Manor Top, City Rd/ Eastern Av Beighton South Anston 53 Wales Mosborough, High St/Station Rd Ridgeway 53a Mosborough, High St/Queen St Halfway, Eckington Way/Tram Terminus Woodall Coal Aston Killamarsh 53a Shireoaks Marsh Lane Eckington, Pinfold St/Bus Stn Apperknowle Renishaw, Renishaw Hall 53, 53a Renishaw, Mulan Restaurant Unstone Renishaw Whitwell Hundall Barlborough, High St/War Memorial Clowne Unstone Green 53 Staveley Clowne, Mill Green Way/Tesco Clowne, Mill Green Way/Tesco Barlow Creswell Stanfree, Clowne Rd/Appletree Inn Shuttlewood, BolsoverElmton Rd/Vivian St Calow Chesterfield Whaley 53a Bolsover, Market Place Bolsover, Market Place Cock Alley Carr Vale Walton Scarclie, Main St West/Horse and Groom Hasland Sutton Scarsdale Palterton, Back Ln/Post Oce Scarclie, Mansfield Rd/Horse and Groom Palterton Heath Doe Lea Glapwell Tupton New Houghton, Rotherham Rd/Recreation Rd Alton database right 2015 Pleasley, Chesterfield -

Development of a Methodology for Estimating Methane Emissions from Abandoned Coal Mines in the UK

1. Development of a Methodology for Estimating Methane Emissions from Abandoned Coal Mines in the UK thinking beyond construction 1. DEVELOPMENT OF A METHODOLOGY FOR ESTIMATING METHANE EMISSIONS FROM ABANDONED COAL MINES IN THE UK May 2005 Reference: REPORT/D5559/SK/May 2005/EMISSIONS/V3 Issue Prepared by: Verified by: Steven Kershaw Keith Whitworth V3 BSc, PhD BSc Associate Associate File Ref: I:\Projects D0000 to D9699\D5559 DEFRA IMC White Young Green Environmental Newstead Court, Little Oak Drive, Sherwood Business Park, Annesley, Nottinghamshire, NG15 0DR. Telephone: 01623 684550 Facsimile: 01623 684551 E-Mail: [email protected] Environmental Consultancy WHITE YOUNG GREEN ENVIRONMENTAL This report has been prepared for and on behalf of DEFRA in response to their particular instructions, and any duty of care to another party is excluded. Any other party using or intending to use this information for any other purpose should seek the prior written consent of IMC White Young Green Environmental. The conclusions reached are those which can reasonably be determined from sources of information, referred to in the report and from our knowledge of current professional practice and standards. Any limitations resulting from the data are identified where possible but both these and our conclusions may require amendment should additional information become available. The report is only intended for use in the stated context and should not be used otherwise. Where information has been obtained from third parties, IMC White Young Green Environmental have made all reasonable efforts to ensure that the source is reputable and where appropriate, holds acceptable quality assurance accreditation. -

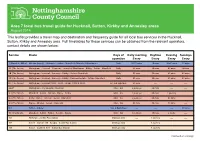

Area 7 Local Bus Travel Guide for Hucknall, Sutton, Kirkby And

Area 7 local bus travel guide for Hucknall, Sutton, Kirkby and Annesley areas August 2014 This leaflet provides a travel map and destination and frequency guide for all local bus services in the Hucknall, Sutton, Kirkby and Annesley area. Full timetables for these services can be obtained from the relevant operators, contact details are shown below. Service Route Days of Early morning Daytime Evening Sundays operation Every Every Every Every 1 (Mansfield Miller) Alfreton (hourly) - Huthwaite - Sutton - Mansfield - Mansfield Woodhouse Daily 10-20 mins 10 mins 30-60 mins 30 mins 3A (The threes) Nottingham - Hucknall - Newstead - Annesley Woodhouse - Kirkby - Sutton - Mansfield Daily 30 mins 30 mins 60 mins 60mins 3B (The threes) Nottingham - Hucknall - Annesley - Kirkby - Sutton - Mansfield Daily 30 mins 30 mins 60 mins 60 mins 3C (The threes) Nottingham - Hucknall - Annesley - Kirkby - Coxmoor Estate - Sutton - Mansfield Daily 30 mins 30 mins 60 mins 60 mins N3 (The threes) Nottingham - Hucknall (0030 - 0230) - Kirkby (0300 & 0330) Fri, Sat night bus 30 mins ---- ---- ---- 8AOT Nottingham - City Hospital - Hucknall Mon - Sat 3 journeys 60 mins ---- ---- 9.1 (The Nines) Mansfield - Sutton - Alfreton - Ripley - Derby Mon - Sat 2 journeys 60 mins 1 journey ---- 9.2 (The Nines) Derby - Ripley - Alfreton - Sutton - Mansfield Mon - Sat 2 journeys 60 mins 60 mins ---- 9.3 (The Nines) Ripley - Alfreton - Sutton - Mansfield Mon - Sat 30 mins 30 mins 30 mins ---- 9.3 Sutton - Alfreton Sun & Bank Hols ---- ---- ---- 60 mins 90 (The Ninety) Mansfield