Trade Mark Inter Partes (0/095/10)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Tri Boulder Official Athlete Guide

2021 TRI BOULDER OFFICIAL ATHLETE GUIDE Long Course Boulder Beast Triathlon & Aquabike Olympic & Sprint Triathlon, Duathlon & Relays Saturday, July 24th, 2021 Boulder Reservoir, 5565 N 51st St Boulder, CO 80301 We can't wait to get to racing at the Boulder Reservoir! Saturday is going to be a great day with temperatures reaching 88°F during the race. The water temperature at Boulder Reservoir as of July 13th is 77°F Packet Pick Up Dates, Times & Locations Thursday, July 22nd 4:00pm - 7:00m Boulder Cycle Sport - North 4580 North Broadway Suite B, Boulder, CO 80304 Friday, July 23rd 3:00pm - 7:00pm Road Runner Sports Westminster 10442 Town Center Dr Suite 300, Westminster, CO 80021 Saturday, July 24th ($10 race day pick up fee) 5:45am - 7:30am Finish Line Trailer Boulder Reservoir Parking Lot / Finish Line Please arrive at least 1 hour before your start time if you plan to pick up your packet on race morning. Race Day Parking - The park entry fee will be waived until 7:15am for everyone, however anyone who arrives after 7:15am should be prepared to pay the regular park entrance fee. Athletes and spectators will follow parking attendants in the morning to the Reservoir’s north or south overflow lots. Water Temp & Sunday’s Expected Weather Forecast – The air temperature on Sunday is expected to reach 88°F by midday. Boulder Reservoir's water temperature is 77°F (as of July 13th). Transition - Only participants will be allowed in transition. If you would like to see your family and friends, make sure they are on the other side of the barricades. -

T-2 Bicycle Retailer & Industry News • Top 100 Retailers 2007 Www

T-2 Bicycle Retailer & Industry News • Top 100 Retailers 2007 www.bicycleretailer.com The Top 100 Retailers for 2007 were selected because they excel in three ar- eas: market share, community outreach and store appearance. However, each store has its own unique formula for success. We asked each store owner to share what he or she believes sets them apart from their peers. Read on to learn their tricks of the trade. denotes repeat Top 100 retailer ACME Bicycle Company Art’s SLO Cyclery Bell’s Bicycles and Repairs Katy, TX San Luis Obispo, CA North Miami Beach, FL Number of locations: 1 Number of locations: 3 Number of locations: 1 Years in business: 12 Years in business: 25 Years in business: 11 Square footage: 15,500 Square footage (main location): 5,000 Square footage: 15,000 Number of employees at height of season: 20 Number of employees at height of season: 20 Number of employees at height of season: 12 Owners: Richard and Marcia Becker Owners: Scott Smith, Eric Benson Owner: James Bell Managers: same Manager: Lucien Gamache Manager: Edlun Gault What sets you apart: Continuous improvement—be it customer What sets you apart: Many things set us apart from our competitors. What sets you apart: We pride ourselves on our service, repairs and service, product knowledge, inventory control, or simply relationship One thing is that we realize customers can shop anywhere. Knowing fi ttings. Most of our guys are certifi ed for repairs. We have a separate building—there is always room to improve. There is always some- this, we create an experience for them above and beyond coming full-service repair shop. -

Download Cycle and Skate Sports Strategy

8/07/15 About this document Contents This document is the DRAFT Cycle Sport and Skate Strategy. A second Trends and Demand ................ 2 volume, the Supporting Document, Cycle sports ........................................ 2 provides more details concerning the Off-road, BMX and mountain biking 2 existing facilities and community Cycle clubs ....................................... 3 engagement findings. Skating and Scooters .......................... 3 Acknowledgements Facilities in Whittlesea ............. 4 City of Whittlesea would like to Cycle sports facilities .......................... 4 acknowledge the support and Skate and scooter facilities ................. 5 assistance provided by: Key Issues and Future • Victorian Government in Directions ................................ 7 partnering to develop the strategy A sustainable planning framework for future provision .................................. 7 Equitable distribution of central, social and easy to get to facilities....... 7 Facilities designed, constructed and managed so they are in line with best practise ............................................. 11 • Project Working Group (including Programs, events and competitions at James Lake, Patricia Hale, James suitable venues ................................. 12 Kempen, Lenice White and Fran One or more sustainable cycle clubs 12 Linardi) Goals ..................................... 13 • Council staff who contributed to the completion of this project Key Directions ....................... 13 • Organisations, retailers, -

Design Concept Rationale Prepared As Part of the Ardeer Green Activity Hub Cycle Sports Facilities Master Plan

Criterium Tracks in Australia 3/02/15 About this document Contents This document is the Design Concept Rationale prepared as part of the Ardeer Green Activity Hub Cycle Sports Facilities Master Plan. The project 2 Cycle sports facilities – concept and Acknowledgments rationale 3 Jeavons Landscape Architects have prepared the The Draft Master Plan 7 master plan for this site. Site design and images 8 Ecology and Heritage Partners prepared the flora and fauna assessment and cultural heritage Attachment 1. review. Meinhardt Engineering prepared the stormwater Criterium tracks in Australia 16 assessment. We thank the following agencies who formed the Project Steering Group, as well as the input provided by VicRoads, and the Footscray Cycle Club. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form, by any means, without the prior written permission of the Brimbank City Council and @leisure Rear 534 Mt Alexander Rd Ascot Vale Vic 3032 03 9326 1662 [email protected] www.atleisure.com.au Jeavons Landscape Architecture CYCLE SPORTS FACILITIES – CONCEPT AND RATIONALE 1 3/02/15 The project Methods The following methods were used in the This project is the Ardeer Green Activity Hub preparation of this document: Master Plan. The project will create a key destination in the west for cycling. • Consultation with Footscray Cycle Club and Cycling Victoria The site chosen for this master plan is an area • Discussions with the Project Steering in the suburb of Ardeer bounded by Forest Group (Department of Health, City Street to the South; the Western Ring Road / West Water, Melbourne Water and M80 to the West; Ballarat Road to the North; City of Brimbank) and the Kororoit Creek to the East (see • Site analysis below). -

2007 CCCX Mountain Bike Race 1 Results: Fort Ord East Garrison, Seaside, CA, 2/11/07

2007 CCCX Mountain Bike Race 1 Results: Fort Ord East Garrison, Seaside, CA, 2/11/07 www.cccx.org JR. MEN 14-18 place number time name team town 1 709 3 laps @ 1.11'16'' Nitish Nag NRL Racing Union City 2 726 2'' Taylor Shamshoian Scotts Valley Cycle Sport Scotts Valley 3 717 45'' Jesse Nickell Harbor High/SCCCC Santa Cruz 4 724 1'53'' Taylor Hohstadt Bicycle Trip Salinas 5 701 2'21'' Jordan Kestler Los Gatos High Los Gatos 6 718 2'31'' Christy Berenger Harbor High Santa Cruz 7 704 2'48'' Anthony Ruh Los Gatos High Monte Sereno 8 706 3'42'' Ben Wild Los Gatos High Los Gatos 9 722 6'04'' Erik Young Harbor High Aptos 10 727 7'00'' Jacob Martin Calvary Chapel High Seaside 11 714 7'03'' Jason Larson Harbor High Santa Cruz 12 703 9'11'' Brian Hamilton Los Gatos High Monte Sereno 13 715 11'15'' Jonathan Mayfield Bicycle Trip Mt. Hermon 14 710 12'35'' KJ Cage Los Gatos High Monte Sereno 15 723 12'54'' Kyle Vanderstoep Harbor High Soquel 16 708 15'03'' Austin Roberts NRL Racing Orinda 17 725 22'42'' Logan Martin Calvary Chapel High Seaside 18 713 23'38'' Robbie Milazzo Harbor High Santa Cruz 19 711 26'09'' Ian Hacker NRL Racing Piedmont 20 720 31'32'' Connor Bridges Harbor High Santa Cruz 21 707 34'57'' Matt Colbran-Patterson Los Gatos High Los Gatos 22 719 37'16'' Connor Hope Harbor High Santa Cruz 23 712 46'33'' Brandon Fant Los Gatos High Los Gatos 24 705 49'34'' Maitrey Shroff NRL Racing Cupertino 25 702 dnf Anthony Contos Los Gatos High Los Gatos 26 716 dnf Jack Johnson Harbor High Santa Cruz BEGINNING MEN 19-34 1 131 3 laps @ 1.18'48'' -

Cycling Victoria State Facilities Strategy 2016–2026

CYCLING VICTORIA STATE FACILITIES STRATEGY 2016–2026 CONTENTS CONTENTS WELCOME 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 INTRODUCTION 4 CONSULTATION 8 DEMAND/NEED ASSESSMENT 10 METRO REGIONAL OFF ROAD CIRCUITS 38 IMPLEMENTATION PLAN 44 CYCLE SPORT FACILITY HIERARCHY 50 CONCLUSION 68 APPENDIX 1 71 APPENDIX 2 82 APPENDIX 3 84 APPENDIX 4 94 APPENDIX 5 109 APPENDIX 6 110 WELCOME 1 through the Victorian Cycling Facilities Strategy. ictorians love cycling and we want to help them fulfil this On behalf of Cycling Victoria we also wish to thank our Vpassion. partners Sport and Recreation Victoria, BMX Victoria, Our vision is to see more people riding, racing and watching Mountain Bike Australia, our clubs and Local Government in cycling. One critical factor in achieving this vision will be developing this plan. through the provision of safe, modern and convenient We look forward to continuing our work together to realise facilities for the sport. the potential of this strategy to deliver more riding, racing and We acknowledge improved facilities guidance is critical to watching of cycling by Victorians. adding value to our members and that facilities underpin Glen Pearsall our ability to make Victoria a world class cycling state. Our President members face real challenges at all levels of the sport to access facilities in a safe, local environment. We acknowledge improved facilities guidance is critical to adding value to our members and facilities underpin our ability to make Victoria a world class cycling state. Facilities not only enable growth in the sport, they also enable broader community development. Ensuring communities have adequate spaces where people can actively and safely engage in cycling can provide improved social, health, educational and cultural outcomes for all. -

Reference List

Cyclus2 – Reference list Universities: Poznań University of Physical Education (Poland) University of Regensburg (Germany) R.O.C. Military Academy, Kaohsiung (Taiwan) Saarland University, Saarbrücken (Germany) Universidad Castilla la Mancha, Ciudad Real (Spain) Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (Germany) University of Lausanne (Switzerland) University of Science, Penang (Malaysia) Stellenbosch University (South Africa) University of Potsdam (Germany) Cheng Shiu University, Kaohsiung City (Taiwan, ROC) University of Taipei (Taiwan, ROC) Jean Monnet University, Saint-Étienne (France) University of Nottingham (Great Britain) University of Bologna (Italy) German Sport University, Cologne (Germany) Leeds Beckett University (Great Britain) Free University of Brussels-VUB (Belgium) University of La Sapienza, Rome (Italy) Universidad de la República Uruguay, Montevideo (Uruguay) Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom (Thailand) University Hospital Reims (France) University of Franche-Comté, Besançon (France) University of Burgundy, Dijon (France) Tibet physical education institute, Lhasa (China) Belarusian National Technical University, Minsk (Belarus) Shizuoka Sangyo University, Iwata (Japan) Jaingxi Normal University, Nanchang (China) The University of Western Australia, Perth (Australia) Maastricht University (The Netherlands) University of Exeter (Great Britain) Shandong Sport University (China) The Swedish School of Sport and Health Science, GIH, Stockholm (Sweden) Ghent University (Belgium) University of Central Missouri, Warrensburg (United -

High Performance Strategic Plan Cycling

WESTERN AUSTRALIAN CYCLING HIGH PERFORMANCE STRATEGIC PLAN Prepared and published by: WestCycle Incorporated With funding and support from: Department of Sport and Recreation Contact: WestCycle Incorporated [email protected] www.westcycle.org.au Acknowledgements: WestCycle would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Western Australian cycling community in the development of this document. Photography: Various Sources Design: Media on Mars, Fremantle, WA Copyright: The information contained in this document may be copied provided prior approval is received from WestCycle and that full acknowledgement is made. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 01 HIGH PERFORMANCE VISION 4 02 CURRENT ENVIRONMENTS 8 Track 9 Road 13 Mountain Bike 17 BMX 21 03 FUTURE FOCUS 26 RESOURCES 40 GLOSSARY 44 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY WestCycle the peak body of cycling their best in state, national and development environment. Strong in Western Australia has prepared international competition. consultation with the Western this High Performance Plan to In addition, the high performance Australian Institute of Sport help shape the successful future environment must nurture and (WAIS) and the development of high performance cycling across identify Western Australia’s next of stronger centralised shared all disciplines. This specific plan generation of athletes, providing resources pathways will result in is focusing on the state talent the right support at the right time not only greater success at a high development area (13-19 years of to ensure Western Australian performance level but also an age.) All disciplines are aligned to athletes continue to achieve increase in participation numbers the Winning Edge aims, which are: international sporting success. from grass roots upwards. -

2021 Technical Guide V1 8/23/2021

2021 TECHNICAL GUIDE V1 8/23/2021 2021 Rochester Cyclocross - TECHNICAL GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION, USCX SERIES, NEW FLYOVER .......................................................................................2 CONTACT INFORMATION .....................................................................................................................3 EVENT SPONSORS ................................................................................................................................4 UCI & USAC OFFICIALS ..........................................................................................................................5 REGULATIONS AND LICENSING .............................................................................................................6 REGISTRATION AND TEAM PARKING ....................................................................................................7 DIRECTIONS AND HOST HOTEL INFORMATION ......................................................................................8 EVENT HISTORY AND COURSE DESCRIPTION .........................................................................................9 COURSE MAPS .................................................................................................………………………….10 & 11 COURSE PROFILES ............................................................................................………………………….12 -

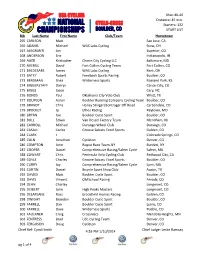

45 Min. Starters: 132 START LIST Bib Last Name First

Men 40-44 Distance: 45 min. Starters: 132 START LIST Bib Last Name First Name Club/Team Hometown 265 CARLSON Matt San Jose, CA 266 ADAMS Michael WAS Labs Cycling Stow, OH 267 ALEGRANTI Jon Superior, CO 268 ANDERSON Eric Indianapolis, IN 269 AUER Kristopher Charm City Cycling LLC Baltimore, MD 270 AVERILL David Fort Collins Cycling Team Fort Collins, CO 271 BALDESARE James WAS Labs Cycling Kent, OH 272 BATEY Robert Feedback Sports Racing Boulder, CO 273 BERGMAN Shea Wilderness Sports Roeland Park, KS 274 BIGGERSTAFF Darryn Canon City, CO 275 BIGGS Jason Cary, NC 276 BONDS Paul Oklahoma City Velo Club Whitt, TX 277 BOUPLON Aaron Boulder Running Company Cycling Team Boulder, CO 278 BRANDT Chris Honey Stinger/Bontrager Off Road Carbondale, CO 279 BROCKET Jp Ethos Racing Raytown, MO 280 BRYAN Joe Boulder Cycle Sport Boulder, CO 281 BULL Edwin Van Dessel Factory Team Mendham, NJ 282 CARROLL Michael Durango Wheel Club Durango, CO 283 CASALI Carlos Groove Subaru Excel Sports Golden, CO 284 CLARK J Colorado Springs, CO 285 COLN Jonathan Cycleton Denver, CO 286 COMPTON John Rogue Race Team-NY Burdett, NY 287 COOPER Daniel Comprehensive Racing/Salem Cycle Salem, MA 288 COWART Chris Peninsula Velo Cycling Club Redwood City, CA 289 COYLE Charles Groove Subaru Excel Sports Boulder, CO 290 CURRY Jay Comprehensive Racing/Salem Cycle Lynn, MA 291 CURTIN Daniel Bicycle Sport Shop Club Austin, TX 292 DAVIES Matt Boulder Cycle Sport Boulder, CO 293 DAVIS Vincent Old School Racing Arvada, CO 294 DEAN Charley Longmont, CO 295 DEIBERT John High Peaks Masters Longmont, CO 296 DELAPLANE Ross brookfield Homes Racing Golden, CO 298 DWIGHT Brandon Boulder Cycle Sport Boulder, CO 299 FARRELL Dan Boulder Cycle Sport Lyons, CO 300 FARRELL Dave Wilderness Sports Pueblo, CO 301 FAULKNER Craig Crossniacs Mendota Heights, MN 302 FENTRESS Brad USC Cycling Team Denver, CO 303 FERGUSON Doug Cycleton Denver, CO Chief Ref: Cyndi Smith 4:53 PM 1/10/2014 Chief Judge: Leslie Ramsay pg 1 of 4 Men 40-44 Distance: 45 min. -

Triathlon Embraces the Family

Running | Hiking | Biking | Paddling Triathlon | Skiing | Fitness | Travel FREE! JUNE 22,000 CIRCULATION COVERING UPSTATE NEW YORK SINCE 2000 2013 SWIMMERS start THE INAUGURAL OLD FORGE TRIathLON IN 2012. COURTESY OF ATC ENDURANCE BIKERS at 2012 NICOLE BECKWITH OF SIDNEY XTERRA SKYHIGH FINISHES THE SPRINT RACE OFF-ROAD TRIathLON WITH HER TWO KIDS at THE IN GRAFTON. 2012 FRONHOFER TOOL CHARLES & GINA TRIathLON IN CAMBRIDGE. SLYER/ASLYERIMAGE. Visit Us on the Web! PHOTO BY FRANK FRONHOFER COM AdkSports.com Facebook.com/AdirondackSports behind them,” said Bridget Crossman, founder and co-race director of the Fronhofer Tool race. “The parents model the life lesson of careful preparation as they train for triathlons, and their children pick up on it.” Bridget added that the addition CONTENTS Triathlon of the kids’ race has helped boost numbers for the main races for adults, both on Saturday, Aug. 3. “Triathlon has never been 1 Triathlon & Duathlon more family-friendly,” she said. Races Embrace the Family MID-SUMMER TRIATHLONS AND KIDS’ RACES 3 Running & Walking Embraces On July 20-21, the SkyHigh Adventures Multi-Sport Life Welcome Summer! Triathlon Festival is now in its 14th year. The SHAPE Kids’ Triathlon is part of the Multi-Sport Life Triathlon Festival week- 5 Around the Region News Briefs end. It includes a 100-meter swim, 5K bike ride on pavement and 5 From the Publisher & Editor the Family trails, and an out-and-back, 1K run on trails and sand. Kids finish to cheering crowds through the same finish line as the XTERRA 6-11 CALENDAR OF EVENTS By Christine McKnight Off-Road and Super Olympic Road triathletes. -

2016 America's Best Bike Shops

TRADE ED -IN IZ PA R R O T H N T E U R A B I C M Y O C .C L K EB O LUEBO 2016 America's Best Bike Shops Business Name City State 2016 2015 2014 2013 Aarons Bicycle Repair Seattle WA 2016 Absolute Bikes - AZ Flagstaff AZ 2016 2015 2014 2013 Absolute Bikes (Colorado) SaliDa CO 2016 2015 2014 2013 Acme Bicycle SHop, LLC Punta GorDa FL 2016 2015 2014 2013 AlameDa Bicycle AlameDa CA 2016 American Cycle & Fitness Macomb TownsHip MI 2016 2015 2014 2013 American Cyclery LLC San Francisco CA 2016 ARB Cyclery Irvine CA 2016 Arriving By Bike™ LLC Eugene OR 2016 2015 Athens Bicycle Athens OH 2016 2015 2014 B&L Bicycles pullman WA 2016 2015 Babcock Bicycles EnDicott NY 2016 2015 Beacon Cycling NORTHFIELD NJ 2016 2015 2014 2013 BeniDorm Bikes Canton CT 2016 2015 2014 2013 BG Bicycles - A professional Bicycle SHop Houma LA 2016 2015 2014 2013 Bicycle Center - BrookfielD BrookfielD CT 2016 2015 2014 Bicycle Center - Port CHarlotte, FL Port CHarlotte FL 2016 2015 2014 Bicycle Gallery - Jacksonville, NC Jacksonville NC 2016 2013 Bicycle Garage of InDy InDianapolis IN 2016 2015 2014 2013 Bicycle Habitat Brooklyn NY 2016 2015 2014 2013 Bicycle JoHn's Santa Clarita Santa Clarita CA 2016 2015 2014 Bicycle PeDaler WicHita KS 2016 2015 2014 2013 Bicycle Pro SHop - AlexanDria AlexanDria VA 2016 Bicycle RancH, Tucson Tucson AZ 2016 2015 Bicycle Sport SHop Austin TX 2016 2015 Bicycle Station - CHeyenne, WY Cheyenne WY 2016 2015 2014 Bicycle WareHouse - San Diego, CA San Diego CA 2016 2015 2014 Bicycle Works - Napa Napa CA 2016 2015 2014 Bicycle WorlD in Mount Kisco