Property and Power: Women Religious Defend Their Rights in Nineteenth-Century Cleveland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frazer Axle Grease

irg W. H. TROXELL, Editor & Publisher. Established by SAMUEL MUTTER,in 1879. TERMS-$1.00 a Year in Advance. MARYLAND, FRIDAY., JUNE 26, 1896 VOL. XVIII. EMMITSBURG, No. s. • DIRECTORY • ACTORS BELIEVE IN had Mr. Renshaw occupied his Us- A Bold Bluff'. Pensive Peneilings. ual plaee, as that seat wascomplete- 'I he gentlemen who had stolen A 12-yeur-old girl is always a great FOR FREDERICK COUNTY MANY SIGNS. Ty demolished. Therefore it seems the horse in Texas had inadvertent- deal more anxiety* to have you look Court. Circuit in his case, at least, he has 'reason ly trotted into a gang of toughs, at the top drawer in her bureau just -Hon. James MeSherry. Chief Judge Lynch and Every human being that lives Asseelate Jridges-Lion. John A. to regard the number thirteen with one of whom owned the horse, and lifter Henderson. she flag cleared it ista.than she Mon. James B. possesses some vein of superstition Attorney-Wm.IL Hinks. more kindness than repulsion. • State's Jordan. foorteen minutes later he was is two weeks afterward. of the Court-John L. in their make up, dun, it stoutly Clerk As this article is intended to deal standing on a barrel at the foot of a Some of the politicians mit 1Vest Orphan's Court. though they do, and to-day the Grinder, Win. R. Young and with superstitions that govern all telegraph pole with a rope making are such rabid `Judges-John W. ,what advocates of silver B. Wilson. wiseet sage who pooh -poolia ilium? -James E. -

Sacred Music Volume 115 Number 3

Volume 115, Number 3 SACRED MUSIC (Fall) 1988 Durham, England. Castle and cathedral SACRED MUSIC Volume 115, Number 3, Fall 1988 FROM THE EDITORS The Polka Mass 3 The Training of the Clergy 4 THE ORDER OF SAINT CECILIA Duane I. CM. Galles 7 THE LEFEBVRE SCHISM Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger 17 SAINT CECILIA OR THE POWER OF MUSIC, A LEGEND 10 REVIEWS 21 NEWS 27 SACRED MUSIC Continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gregory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Association of America. Office of publications: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103. Editorial Board: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler, Editor Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Rev. John Buchanan Harold Hughesdon William P. Mahrt Virginia A. Schubert Cal Stepan Rev. Richard M. Hogan Mary Ellen Strapp Judy Labon News: Rev. Msgr. Richard J. Schuler 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 Music for Review: Paul Salamunovich, 10828 Valley Spring Lane, N. Hollywood, Calif. 91602 Paul Manz, 1700 E. 56th St., Chicago, Illinois 60637 Membership, Circulation and Advertising: 548 Lafond Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55103 CHURCH MUSIC ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA Officers and Board of Directors President Monsignor Richard J. Schuler Vice-President Gerhard Track General Secretary Virginia A. Schubert Treasurer Earl D. Hogan Directors Rev. Ralph S. March, S.O. Cist. Mrs. Donald G. Vellek William P. Mahrt Rev. Robert A. Skeris Membership in the CMAA includes a subscription to SACRED MUSIC. Voting membership, $12.50 annually; subscription membership, $10.00 annually; student membership, $5.00 annually. -

2019-20 Atlantic 10 Commissioner's Honor Roll

2019-20 Atlantic 10 Commissioner’s Honor Roll Name Sport Year Hometown Previous School Major DAVIDSON Alexa Abele Women's Tennis Senior Lakewood Ranch, FL Sycamore High School Economics Natalie Abernathy Women's Cross Country/Track & Field First Year Student Land O Lakes, FL Land O Lakes High School Undecided Cameron Abernethy Men's Soccer First Year Student Cary, NC Cary Academy Undecided Alex Ackerman Men's Cross Country/Track & Field Sophomore Princeton, NJ Princeton High School Computer Science Sophia Ackerman Women's Track & Field Sophomore Fort Myers, FL Canterbury School Undecided Nico Agosta Men's Cross Country/Track & Field Sophomore Harvard, MA F W Parker Essential School Undecided Lauryn Albold Women's Volleyball Sophomore Saint Augustine, FL Allen D Nease High School Psychology Emma Alitz Women's Soccer Junior Charlottesville, VA James I Oneill High School Psychology Mateo Alzate-Rodrigo Men's Soccer Sophomore Huntington, NY Huntington High School Undecided Dylan Ameres Men's Indoor Track First Year Student Quogue, NY Chaminade High School Undecided Iain Anderson Men's Cross Country/Track & Field Junior Helena, MT Helena High School English Bryce Anthony Men's Indoor Track First Year Student Greensboro, NC Ragsdale High School Undecided Shayne Antolini Women's Lacrosse Senior Babylon, NY Babylon Jr Sr High School Political Science Chloe Appleby Women's Field Hockey Sophomore Charlotte, NC Providence Day School English Lauren Arkell Women's Lacrosse Sophomore Brentwood, NH Phillips Exeter Academy Physics Sam Armas Women's Tennis -

Catholic Educational Exhibit Final Report, World's Columbian

- I Compliments of Brother /Tfcaurelian, f, S. C. SECRETARY AND HANAGER i Seal of the Catholic Educational Exhibit, World's Columbian Exposition, 1893. llpy ' iiiiMiF11 iffljy -JlitfttlliS.. 1 mm II i| lili De La Salle Institute, Chicago, III. Headquarters Catholic Educational Exhibit, World's Fair, 1S93. (/ FINAL REPORT. Catholic Educational Exhibit World's Columbian Exposition Ctucaofo, 1893 BY BROTHER MAURELIAN F. S. C, Secretary and Manager^ TO RIGHT REVEREND J. L. SPALDING, D. D., Bishop of Peoria and __-»- President Catholic Educational ExJiibit^ WopIgT^ F^&ip, i8qt I 3 I— DC X 5 a a 02 < cc * 5 P3 2 <1 S w ^ a o X h c «! CD*" to u 3* a H a a ffi 5 h a l_l a o o a a £ 00 B M a o o w a J S"l I w <5 K H h 5 s CO 1=3 s ^2 o a" S 13 < £ a fe O NI — o X r , o a ' X 1 a % a 3 a pl. W o >» Oh Q ^ X H a - o a~ W oo it '3 <»" oa a? w a fc b H o £ a o i-j o a a- < o a Pho S a a X X < 2 a 3 D a a o o a hJ o -^ -< O O w P J tf O - -n>)"i: i i'H-K'i4ui^)i>»-iii^H;M^ m^^r^iw,r^w^ ^-Trww¥r^^^ni^T3r^ -i* 3 Introduction Letter from Rig-lit Reverend J. Ij. Spalding-, D. D., Bishop of Peoria, and President of the Catholic Educational Exhibit, to Brother Maurelian, Secretary and Manag-er. -

To Serve, and That We Disciples of Jesus Are Called to Do the Same

CHRIST THE KING SEMINARY TO 2012SERVECHRIST | 2013 Annual THE Report KING SEMINARY 2012 | 2013 Annual Report TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE ............................ PAGE 3 RECTOR’S MESSAGE ................................. PAGE 4 BOARD OF TRUSTEES ............................... PAGE 5 PRIESTLY FORMATION .............................. PAGE 6 DEACONS – MEN OF SERVICE ..................PAGE 10 STRENGTHENING OUR PARISHES ............ PAGE 12 STRENGTHENING OUR DIOCESE ............. PAGE 14 CURÉ OF ARS AWARDS DINNER ............... PAGE 18 VISIONING FOR THE FUTURE ..................PAGE 19 FINANCIAL POSITION ............................ PAGE 20 BEING HERE FOR THE SEMINARY ............. PAGE 21 HERITAGE SOCIETY ................................ PAGE 22 MISSION STATEMENT ..................... BACK COVER CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE MOST REVEREND RICHARD J. MALONE BISHOP OF BUFFALO / CHAIRMAN, BOARD OF TRUSTEES Dear Friends in Christ, Serving as bishop of Buffalo for more than a year now, I have seen firsthand how Christ the King Seminary strengthens our diocese as our local center for faith formation and evangelization. As a long-time educator, I have always had a special affinity for seminaries and higher theological education. I must say how truly impressed I am with the caliber of students, faculty and programs at Christ the King. It is, therefore, my pleasure to present to you this annual report for Christ the King Seminary, on behalf of the entire Board of Trustees. In this report you will read about the Seminary’s successes over the past year and learn about new programs and initiatives aimed at strengthening our diocese, our Seminary and our parishes for the future. As examples, the Seminary recently completed an arduous reaccreditation process and I offer my sincere thanks to all those involved for their hard work. “ I have met so The Seminary is also playing a key role in helping to develop the new parish administrator ministry in the diocese. -

Logos--Fall2008final.Pdf

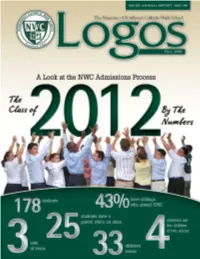

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT As the Father has sent me, so I send you. John 20:21 Missio (Latin, nom.) – sent. Mission, derived from the Latin missionem, mission from mittere “to send.” The Northwest Catholic story is a story of a journey – a journey that we hope will be a transformative experience for the maturing young adults who come here to learn, but also to grow in their relationship with God and others. At the start of each year, we introduce a theme that is woven into the academic and co-curricular program. This year, we are focusing on the jubilee celebration of the apostle Paul. In this well-known story, Paul reaches a critical point in his personal journey, a point where he is brought into a relationship with God and then is sent out into the world to spread the Good News. He is brought in, transformed, then sent out. Paul’s complete conversion represents a radical transformation in his life. For most of us, understanding how God calls us to our true selves is an incremental journey. The young men and women who join us follow a four-year journey through a unique Northwest Catholic culture where they can better understand how they are called to serve this world. We assist them in their journey by challenging them intellectually, physically, creatively, socially, and spiritually. We also encourage them to see how service to others is an essential ingredient in their ultimate journey -- a full and rich life. The Class of 2012, drawn from 33 towns, enters into a social climate composed of different races, religions, ethnicities, economic backgrounds, and social structures. -

A New Century and New Ventures

Chapter 4 A New Century and New Ventures he men who would lead the province withdraw the Society from any parish that did not in the first decades of the 20th century have either a college or at least the prospects of a would bring to their post a variety of college attached to it. While Fr. McKinnon was not experiences. With the resignation of Fr. anxious for the Society to lose the parish where so Purbrick 47-year-old Fr. Thomas Gannon, much effort had just been expended to build the TSJ, was appointed as his successor. Gannon had been new church, more importantly, he recognized that rector-president of St. John’s College (Fordham) for there was a growing need for a school that would four years and served several stints as socius to the cater to the educational and religious needs of the provincial. He would later serve as tertian instructor sons of wealthy Catholics in New York City.36 There and then have the distinction of being the first were a number of private day schools in Manhattan American Assistant to the Superior General when that catered to the children of the wealthy and it the United States was separated from the English was to these that the growing number of well-to-do Assistancy in 1915. He would be succeeded in the Catholics had often turned to educate their sons. office by Fr. Joseph Hanselman, SJ. Born in 1856 Rightly fearing - at a time when prejudice against and entering the Society in 1878, Fr. Hanselman Catholics was not unknown - that the atmosphere had spent most of his priestly life at the College in these schools was not conducive to the spiritual of the Holy Cross, first as prefect of discipline and development of Catholic young men, Fr. -

Volume 24 Supplement

2 GATHERED FRAGMENTS Leo Clement Andrew Arkfeld, S.V.D. Born: Feb. 4, 1912 in Butte, NE (Diocese of Omaha) A Publication of The Catholic Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania Joined the Society of the Divine Word (S.V.D.): Feb. 2, 1932 Educated: Sacred Heart Preparatory Seminary/College, Girard, Erie County, PA: 1935-1937 Vol. XXIV Supplement Professed vows as a Member of the Society of the Divine Word: Sept. 8, 1938 (first) and Sept. 8, 1942 (final) Ordained a priest of the Society of the Divine Word: Aug. 15, 1943 by Bishop William O’Brien in Holy Spirit Chapel, St. Mary Seminary, Techny, IL THE CATHOLIC BISHOPS OF WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA Appointed Vicar Apostolic of Central New Guinea/Titular Bishop of Bucellus: July 8, 1948 by John C. Bates, Esq. Ordained bishop: Nov. 30, 1948 by Samuel Cardinal Stritch in Holy Spirit Chapel, St. Mary Seminary Techny, IL The biographical information for each of the 143 prelates, and 4 others, that were referenced in the main journal Known as “The Flying Bishop of New Guinea” appears both in this separate Supplement to Volume XXIV of Gathered Fragments and on the website of The Cath- Title changed to Vicar Apostolic of Wewak, Papua New Guinea (PNG): May 15, 1952 olic Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania — www.catholichistorywpa.org. Attended the Second Vatican Council, Sessions One through Four: 1962-1965 Appointed first Bishop of Wewak, PNG: Nov. 15, 1966 Appointed Archbishop of Madang, PNG, and Apostolic Administrator of Wewak, PNG: Dec. 19, 1975 Installed: March 24, 1976 in Holy Spirit Cathedral, Madang Richard Henry Ackerman, C.S.Sp. -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

Commencement Program, 6-11-1956 John Carroll University

John Carroll University Carroll Collected Commencement Programs University 6-11-1956 Commencement Program, 6-11-1956 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/commencementprograms Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "Commencement Program, 6-11-1956" (1956). Commencement Programs. 19. http://collected.jcu.edu/commencementprograms/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in Commencement Programs by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEVENTIETH A NNlllJAJIL (?~ 10 ~VJ\[ ~VJ\UlEN f!]IE~VJIU I EN11L JOHN CARROLL UNIVERSITY MONDAY JUNE ll, 1956 3:00P . M. UNIVERSITY HEIGHTS, OHIO ORDER OF EXERCISES Processional ANNOUNCEMENTS Very Reverend Frederick E. W elfle, S.J. President of John Carroll University ADDRESS TO THE GRADUATES Honorable Paul Martin Minister of National Health and Welfare Ottawa, Canada COKFERRING OF DEGREES BENEDICTION Rt. Rev. Msgr. 0. A. Mazanec Pastor of St. Rita's Parish Solon, Ohio Recessional DEGREES IN COURSE COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Candidates will he presented by REVEREND EDWARD C. McCUE, .J., Ph.D., S.T.L. Dean Bachelor of Arts John Patrick Elkanich, John Louis Nowlan cum laude Vincent Chri topher Puozo, John Aloysius English summa cum laude Raymond Franklin Jasko, cum umde Robert Joseph Reitz Edward Pierre LaMarche Henry Anthony Strater, Thomas Arthur Lichtle magna cum laude Philip Joseph Murawa John Philip Naims, Robert Hugh Thein magna cum laude James Francis Vargo Bachelor of Science in Social Science Thomas James Behm William Mark Devine, Jr. -

The Development of US Roman Catholic Church Lay Leaders

The Development of U.S. Roman Catholic Church Lay Leaders For a Future with Fewer Priests A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education (Ed.D) in the Urban Educational Leadership program of the College of Education, Criminal Justice, and Human Services 2013 by Gloria Jean Parker-Martin B.S., University of Cincinnati, 1974 M.B.A., Xavier University, 1979 Committee Chair: Mary Brydon-Miller, PhD ii Abstract The Catholic Church of the United States is facing a future with fewer priests. The diminishing number means many more parishes will be without a resident pastor, and some parishes will no longer have a priest available to them at all. The trend makes it more likely that new models of ministry will need to be launched to maintain Catholic faith communities throughout the country. It is likely more and more responsibility for the growth of such churches will rest with lay leaders. This study looks at the problem through the lens of Change Theory with the methodology of Action Research. This report examines the effects of the priest shortage trends on St. Anthony Parish in Madisonville, and the efforts to define the best ministerial and administrative structure for its lay people to position the parish within a Pastoral Region in the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. For the U.S. Church to survive the laity must begin to take on roles that priests once held. There is a new vigor for the laity, particularly women, to assume stronger roles in the parishes. -

Irish Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland

Irish Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland Irish Americans and Their Communities of Cleveland Nelson Callahan and William Hickey MSL Academic Endeavors CLEVELAND, OHIO This electronic edition contains the complete text as found in the print edition of the book. Original copyright to this book is reserved by the author(s). Organizations and individuals seeking to use these materials outside the bounds of fair use or copyright law must obtain permission directly from the appropriate copyright holder. For more information about fair use, see the Michael Schwartz Library’s copyright guide: http://researchguides.csuohio.edu/ copyright/fairuse. Any permitted use of this edition must credit the Cleveland State University Michael Schwartz Library and MSL Academic Endeavors as the source. Cleveland Ethnic Heritage Studies, Cleveland State University The activity which is the subject of this report was supported in part by the U.S. Office of Education, Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. However, the opinions expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Office of Education, and no official endorsement by the U.S. Office of Education should be inferred. The original print publication was made possible by a grant from the GEORGE GUND FOUNDATION. Copyright © by Cleveland State University v Preface The history of Cleveland is intimately connected with the settlement of the Irish immigrants. Their struggle for survival in the early days, their social, plitical and economic upward movement as well as their impact on the growth of Cleveland is vividly portrayed in this monograph by two distinguished Clevelanders, Nelson J. Callahan and William P.