THE DIABETIC NEUROPATHIES: TYPES, DIAGNOSIS and MANAGEMENT J Gareth Llewelyn *Ii15

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diabetic Neuropathy

6 Diabetic Neuropathy Solomon Tesfaye, MD, FRCP INTRODUCTION Polyneuropathy is one of the commonest complications of the diabetes and the com- monest form of neuropathy in the developed world. Diabetic polyneuropathy encompasses several neuropathic syndromes, the most common of which is distal symmetrical neuropa- thy, the main initiating factor for foot ulceration. The epidemiology of diabetic neuropathy has recently been reviewed in reasonable detail (1). Several clinic- (2,3) and population- based studies (4,5) show surprisingly similar prevalence rates for distal symmetrical neu- ropathy, affecting about 30% of all people with diabetes. The EURODIAB prospective complications study, which involved the examination of 3250 patient with type 1 from 16 European countries, found a prevalence rate of 28% for distal symmetrical neuropathy (2). After excluding those with neuropathy at baseline, the study showed that over a 7-year period, about one-quarter of patients with type 1 diabetes developed distal symmetrical neuropathy; age, duration of diabetes, and poor glycemic control being major determinants (6). The development of neuropathy was also associated with potentially modifiable car- diovascular risk factors such as serum lipids, hypertension, body mass index, and cigaret smoking (6). Furthermore, cardiovascular disease at baseline carried a twofold risk of neu- ropathy, independent of cardiovascular risk factors (6). Based on recent epidemiological studies, correlates of diabetic neuropathy include increasing age, increasing duration of dia- betes, poor glycemic control, retinopathy, albuminuria, and vascular risk factors (1,2,4,6). The differing clinical presentation of the several neuropathic syndromes in diabetes sug- gests varied etiological factors. CLASSIFICATION Clinical classification of the various syndromes of diabetic peripheral neuropathy has proved difficult. -

Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

PHYSICIAN REFERRAL DIABETIC PATIENT’S NAME: PERIPHERAL _________________________________ _________________________________ NEUROPATHY DIAGNOSIS: _________________________________ _________________________________ PRECAUTIONS: BACCI & GLINN _________________________________ PHYSICAL THERAPY, INC. _________________________________ For more information on this and _____ Evaluate and Treat other topics, visit our website at: “Therapy with a Difference” _____ Exercise Program (i.e. home, gym) www.bandgpt.com _____ Functional Conditioning _____ Therapeutic Exercise _____ Balance Training _____ Aquatic Therapy (Hanford only) BACCI & GLINN _____ Modalities PHYSICAL THERAPY, INC. _____ Other ______________________ COMMENTS: _____________________ 5533 West Hillsdale Avenue, Suite A Visalia, CA 93291 ________________________________ Phone: 559-733-2478 Frequency: ___ x per week for ___ weeks Fax: 559-733-2470 Signature: _________________________ 331 North 11th Avenue (Physician signature) Hanford, CA 93230 Date: __________ Phone: 559-582-1027 Fax: 559-582-8105 SAME DAY APPOINTMENTS AVAILABLE Referrals are accepted from any physician. A physician’s order and diagnosis are required for evaluation and treatment. We accept most insurances including Medicare. Johnson Designs Bacci & Glinn Physical Therapy, Inc. Hanford: 559-582-1027 Visalia: 559-733-2478 Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy What is Diabetic Signs and Symptoms of Treatment Options Peripheral Neuropathy? Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy There is no cure for diabetic neuropa- Diabetic neuropathy is a nerve ♦ Tingling, tightness, or burning, shooting thy. Treatment focuses on slowing the disorder commonly caused by or stabbing pain in feet, hands, or other progression of the disease. Your diabetes. High blood sugar levels parts of the body. physician will determine the best from diabetes can damage nerves ♦ Reduced feeling or numbness, most treatment for your peripheral neuropa- throughout the body. About 50% of often in the feet. -

Diabetic Neuropathy

PRIMER Diabetic neuropathy Eva L. Feldman1*, Brian C. Callaghan1, Rodica Pop-Busui2, Douglas W. Zochodne3, Douglas E. Wright4, David L. Bennett5, Vera Bril6,7, James W. Russell8 and Vijay Viswanathan9 Abstract | The global epidemic of prediabetes and diabetes has led to a corresponding epidemic of complications of these disorders. The most prevalent complication is neuropathy , of which distal symmetric polyneuropathy (for the purpose of this Primer, referred to as diabetic neuropathy) is very common. Diabetic neuropathy is a loss of sensory function beginning distally in the lower extremities that is also characterized by pain and substantial morbidity. Over time, at least 50% of individuals with diabetes develop diabetic neuropathy. Glucose control effectively halts the progression of diabetic neuropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus, but the effects are more modest in those with type 2 diabetes mellitus. These findings have led to new efforts to understand the aetiology of diabetic neuropathy , along with new 2017 recommendations on approaches to prevent and treat this disorder that are specific for each type of diabetes. In parallel, new guidelines for the treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy using distinct classes of drugs, with an emphasis on avoiding opioid use, have been issued. Although our understanding of the complexities of diabetic neuropathy has substantially evolved over the past decade, the distinct mechanisms underlying neuropathy in type 1 and type 2 diabetes remains unknown. Future discoveries on disease pathogenesis will be crucial to successfully address all aspects of diabetic neuropathy , from prevention to treatment. The International Diabetes Federation estimates that neuropathies secondary to diabetes can occur (Fig. -

Diabetic Neuropathy: a Position Statement by the American

136 Diabetes Care Volume 40, January 2017 Diabetic Neuropathy: A Position Rodica Pop-Busui,1 Andrew J.M. Boulton,2 Eva L. Feldman,3 Vera Bril,4 Roy Freeman,5 Statement by the American Rayaz A. Malik,6 Jay M. Sosenko,7 and Dan Ziegler8 Diabetes Association Diabetes Care 2017;40:136–154 | DOI: 10.2337/dc16-2042 Diabetic neuropathies are the most prevalent chronic complications of diabetes. This heterogeneous group of conditions affects different parts of the nervous system and presents with diverse clinical manifestations. The early recognition and appropriate man- agement of neuropathy in the patient with diabetes is important for a number of reasons: 1. Diabetic neuropathy is a diagnosis of exclusion. Nondiabetic neuropathies may be present in patients with diabetes and may be treatable by specific measures. 2. A number of treatment options exist for symptomatic diabetic neuropathy. 3. Up to 50% of diabetic peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic. If not recognized and if preventive foot care is not implemented, patients are at risk for injuries to their insensate feet. 4. Recognition and treatment of autonomic neuropathy may improve symptoms, POSITION STATEMENT reduce sequelae, and improve quality of life. Among the various forms of diabetic neuropathy, distal symmetric polyneurop- athy (DSPN) and diabetic autonomic neuropathies, particularly cardiovascular au- tonomic neuropathy (CAN), are by far the most studied (1–4). There are several 1 atypical forms of diabetic neuropathy as well (1–4). Patients with prediabetes may Division of Metabolism, Endocrinology & Diabe- – tes, Department of Internal Medicine, University also develop neuropathies that are similar to diabetic neuropathies (5 10). -

Nerve Pain in Diabetes

Information O from Your Family Doctor Nerve Pain in Diabetes What is nerve pain in diabetes? feeling in your feet and it affects your balance, Nerve pain with diabetes is called neuropathy there are special shoes that can help. (new-ROP-uh-thee). It is common in people with uncontrolled diabetes. It usually starts in What can I expect? the feet and may go up the legs. It may cause Medicine will lessen the pain for many patients, burning pain or a loss of feeling. but most will still have some pain. It is also important to wear proper fitting shoes. And, What causes it? every time you see the doctor, have the doctor Nerves are like wires that bring feeling to your check your feet for injuries you cannot feel. brain from other parts of the body. High blood sugar levels can damage those nerves. The Where can I get more information? longer you have high blood sugar, the more Your doctor likely you are to get nerve damage. The nerves AAFP’s Patient Education Resource in your feet are usually the first to be damaged. http://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases- Nerves in other parts of the body can be conditions/diabetic-neuropathy.html damaged, too. American Diabetes Association http://www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/ How do I know if I have it? complications/neuropathy/peripheral-neuropathy.html If you have nerve damage in your feet, you will National Institutes of Health and National Institute of notice pain or loss of feeling. Your doctor can Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases do tests to be sure that is what is causing the http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health- problem. -

Diabetic Neuropathies: the Nerve Damage of Diabetes

Diabetic Neuropathies: The Nerve Damage of Diabetes National Diabetes Information Clearinghouse What are diabetic • neurovascular factors, leading to dam age to the blood vessels that carry neuropathies? oxygen and nutrients to nerves Diabetic neuropathies are a family of nerve • autoimmune factors that cause inflam disorders caused by diabetes. People with U.S. Department mation in nerves of Health and diabetes can, over time, develop nerve dam Human Services age throughout the body. Some people with • mechanical injury to nerves, such as nerve damage have no symptoms. Others carpal tunnel syndrome NATIONAL may have symptoms such as pain, tingling, INSTITUTES • inherited traits that increase susceptibil OF HEALTH or numbness—loss of feeling—in the hands, ity to nerve disease arms, feet, and legs. Nerve problems can • lifestyle factors, such as smoking or occur in every organ system, including the alcohol use digestive tract, heart, and sex organs. About 60 to 70 percent of people with diabe What are the symptoms of tes have some form of neuropathy. People with diabetes can develop nerve problems at diabetic neuropathies? any time, but risk rises with age and longer Symptoms depend on the type of neuropathy duration of diabetes. The highest rates of and which nerves are affected. Some people neuropathy are among people who have with nerve damage have no symptoms at all. had diabetes for at least 25 years. Diabetic For others, the first symptom is often numb neuropathies also appear to be more com ness, tingling, or pain in the feet. Symptoms mon in people who have problems control are often minor at first, and because most ling their blood glucose, also called blood nerve damage occurs over several years, sugar, as well as those with high levels of mild cases may go unnoticed for a long time. -

Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy

DIABETIC PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY What is Diabetic that can become infected and may constricted blood vessels produce Peripheral Neuropathy? not heal. This serious complication of damage to the nerves. iabetic neuropathy is nerve diabetes can lead to loss of a foot, a As diabetic peripheral neuropathy D damage caused by diabetes. leg, or even a life. progresses, various nerves are The type of neuropathy occurring in affected—and these damaged nerves the arms, hands, legs and feet is Signs and Symptoms can cause problems that encourage known as diabetic peripheral Depending on the type(s) of nerves development of ulcers. For example: neuropathy. Diabetic peripheral involved, one or more signs and • Deformities (such as bunions or neuropathy is different from symptoms may be present in hammertoes) resulting from peripheral arterial disease (poor diabetic peripheral neuropathy. motor neuropathy may cause circulation), which affects the blood For sensory neuropathy: shoes to rub against toes, creating vessels rather than the nerves. • Numbness or tingling in the feet a sore. The numbness caused Three different groups of • Pain or discomfort in the feet or by sensory neuropathy can make nerves can be affected by diabetic legs—including prickly,sharp the patient unaware that this is neuropathy: pain or burning feet happening. • Sensory nerves, which enable For motor neuropathy: people to feel pain, temperature, • Muscle weakness and loss of and other sensations muscle tone in the feet and Motor Neuropathy (Deformity) • Motor nerves, which control the lower legs + muscles and give them their • Loss of balance strength and tone • Changes in foot shape that can Ill-fitting Shoes • Autonomic nerves, which allow lead to areas of increased pressure + the body to perform certain For autonomic neuropathy: Sensory Neuropathy involuntary functions, such as • Dry feet (Numbness) sweating. -

Clinical Polyneuropathy Does Not Increase with Prediabetes Or

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Clinical polyneuropathy does not increase with prediabetes or metabolic syndrome in the Japanese general population Seigo Kurisu1,2, Hideyuki Sasaki3* , Shohei Kishimoto2,4, Kazuhiro Hirayasu1, Kinichi Ogawa5, Shohei Matsuno2, Hiroto Furuta2 , Mikio Arita6,KeigoNaka4,KishioNanjo4, Takashi Akamizu2 1Department of Medicine, Kihoku Hospital, 2First Department of Medicine, 3Division of Diabetes and Metabolism, Satellite Clinic for Integrative and Anti-Aging Medicine, Wakayama Medical University, 4Wakayama Rosai Hospital, Wakayama, 5Kansai University of Health Sciences, Osaka, and 6Health-promotion Research Center, Wakayama, Japan Keywords ABSTRACT Metabolic syndrome, Prediabetes, Aims/Introduction: The prevalence of clinical polyneuropathies (ClinPNs) or nerve con- Prevalence of symmetric sensorimotor duction abnormality (NCA) in the groups stratified by glucose tolerance, individual compo- polyneuropathy nents of metabolic syndrome (metabolic syndrome [MetS] components: hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity) and MetS defined by the International Diabetes Federation consen- *Correspondence sus was investigated in the Japanese general population. Factors associated with ClinPN Hideyuki Sasaki and NCA were also identified. Tel.: +81-73-488-1930 Materials and Methods: A total of 625 examinees of regional medical checkup pro- Fax: +81-73-488-1931 grams were recruited to this cross-sectional study. ClinPNs were diagnosed by the Toronto E-mail address: [email protected] Consensus. NCA was judged by at least one bilateral abnormality of sural nerve action poten- tial amplitude or conduction velocity measured by a point-of-care nerve conduction device J Diabetes Investig 2019 (DPNCheck). Clinical factors associated with ClinPNs or NCA were examined by multiple logistic regression analysis. Deteriorating factors of sural nerve action potential amplitude or doi: 10.1111/jdi.13058 conduction velocity values were also investigated in participants without diabetes (n = 550). -

PREVALENCE of PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY in NEWLY DIAGNOSED TYPE 2 DIABETICS Arindam Dutta*, Santa Naorem**, Th

PREVALENCE OF PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY IN NEWLY DIAGNOSED TYPE 2 DIABETICS Arindam Dutta*, Santa Naorem**, Th. Premchand Singh ***, Kunjabashi Wangjam**** ABSTRACT The prevalence and the risk factors of peripheral neuropathy in the newly diagnosed or detected type Our objective was to determine the prevalence and 2 diabetics in Manipur were evaluated. risk factors of peripheral neuropathy in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. One hundred MATERIALS AND METHODS newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients attending Diabetes Clinic, Regional Institute of Medical One hundred newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic Sciences, Imphal were randomly selected for clinical patients attending the Diabetes Clinic, Regional and electrophysiological studies for diagnosis of Institute of Medical Sciences, Imphal, Manipur from peripheral neuropathy. Peripheral neuropathy was March 2002 to September 2003 were selected evaluated by using Neuropathy Symptoms Score randomly for the study. Patients with chronic renal (NSS), Neuropathy Disability Score (NDS) and Nerve failure, chronic liver disease, chronic airways disease, Conduction Studies (NCV) and the diagnosis of carcinoma, infections and critical illness are excluded peripheral neuropathy was made when two or more from the study. The diagnosis of type 2 diabetes of the three abnormalities of NSS, NDS and NCV were was done according to the criteria laid down by present. American Diabetic Association (1997). A detailed clinical history was taken using a structured 29 patients (29%), 17 males (28%) and 12 females questionnaire. A complete clinical examination was (31%) of the 100 newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic done including the height and weight in light clothes. patients had peripheral neuropathy. Multiple logistic Body mass index was calculated using the formula regression analysis shows that duration of diabetes weight in kilograms divided by height in meters has maximum contribution and age, systolic blood squared. -

Diabetic Neuropathy?

Why Diabetic Neuropathy? • Diabetes is the most common cause of Diabetic Neuropathy peripheral neuropathy in the western countries • There are 20.8 million Americans with Bakri Elsheikh, MD diabetes mellitus The Ohio State University Medical Center • Nearly one third are undiagnosed • There are 54 million Americans who have pre-diabetes American Diabetes Association - http://www.diabetes.org Diabetic Neuropathy Talk Outline Why Diabetic Neuropathy? • Why diabetic neuropathy? • What is diabetic neuropathy ? • Diabetic neuropathy is a major contributory factor • How common is diabetic neuropathy in the pathogenesis of • Who gets diabetic neuropathy? foot ulceration and • How to recognize the different types? Charcot joints • How to evaluate diabetic neuropathy? • How does hyperglycemia causes peripheral • 15% of diabetics develop neuropathy? foot ulcer during life time • How to treat it? • What is the future prospective? 1 What is Diabetic The Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy? Neuropathy Study Neuropathy type Type 1 Type 2 • A simple definition of DN for clinical Any neuropathy 66% 59% practice is Distal neuropathy 54% (15%) 45% (13%) “ The presence of symptoms and/or signs of CTS 33% (11%) 35% (6%) peripheral nerve dysfunction in people with Autonomic 7% 5% diabetes after exclusion of other causes” Ulnar neuropathy 2% 2% Boulton AJM et al. Diabet Med 1998 LSRPN 1% 1% • About 10%of diabetic patients had neurologic deficits attributable to non-diabetic causes Dyck PJ et al. Neurology 1993 How common is Staging Severity of diabetic neuropathy? Diabetic Neuropathy • N0: No objective evidence of DN • A prospective study of 4400 patients found • N1: Asymptomatic polyneuropathy 8% had neuropathy at the time of N1a: No symptoms, no signs, abnormal diagnosis, and 50% after 25 years test N1b: No symptoms, abnormal signs, Pirart J. -

Diabetic Testing

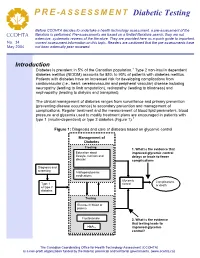

PRE -ASSESSMENT Diabetic Testing Before CCOHTA decides to undertake a health technology assessment, a pre-assessment of the literature is performed. Pre-assessments are based on a limited literature search; they are not CCOHTA extensive, systematic reviews of the literature. They are provided here as a quick guide to important, No. 34 current assessment information on this topic. Readers are cautioned that the pre-assessments have May 2004 not been externally peer reviewed. Introduction Diabetes is prevalent in 5% of the Canadian population.1 Type 2 non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) accounts for 85% to 90% of patients with diabetes mellitus. Patients with diabetes have an increased risk for developing complications from cardiovascular (i.e., heart, cerebrovascular and peripheral vascular) disease including neuropathy (leading to limb amputation), retinopathy (leading to blindness) and nephropathy (leading to dialysis and transplant). The clinical management of diabetes ranges from surveillance and primary prevention (preventing disease occurrence) to secondary prevention and management of complications. Regular treatment and the measurement of blood lipid parameters, blood pressure and glycemia used to modify treatment plans are encouraged in patients with type 1 (insulin-dependent) or type 2 diabetes (Figure 1).1 Figure 1: Diagnosis and care of diabetes based on glycemic control Management of Diabetes Treating:Treating 1. What is the evidence that LifestyleEducation –about physical improved glycemic control nutritional,lifestyle, nutrition and and delays or leads to fewer disease knowledge complications education Diagnosis and and screening screening AntihyperglycemicAntihyperglycemic medications Glycemic Complications Type 1 control Type 1 or death or typetype 2 2 diabetes diabetes Testing:Testing GlucoseFasting in bloodplasma or plasmaglucose Fructosamine 2. -

Renal Transplantation in Diabetic Nephropathy

BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 285 11 DECEMBER 1982 1713 Br Med J (Clin Res Ed): first published as 10.1136/bmj.285.6356.1713 on 11 December 1982. Downloaded from MEDICAL PRACTICE Occasional Survey Renal transplantation in diabetic nephropathy M GONZALEZ-CARRILLO, A MOLONEY, M BEWICK, V PARSONS, C J RUDGE, P J WATKINS Abstract peripheral nerves, and some patients are incapacitated by these Forty diabetics who had developed- end-stage renal problems. Many centres have therefore been reluctant to under- take renal transplantation in diabetics especially where resources failure from diabetic nephropathy and underwent renal have been transplantation have been followed up from one to six limited. Since 1966, however, patients with diabetic years. After one and two years 63% and 42% survived nephropathy attending the University of Minnesota have been (45 and 33 respectively with accepted into the transplant programme, and this centre has now % % functioning kidneys). the world's greatest experience in treating this disease. The Older patients, those with coronary and peripheral less in vascular disease, and those with severe are results, although satisfactory than non-diabetics, have neuropathy been very encouraging.5 -1 prone to higher postoperative morbidity and mortality. http://www.bmj.com/ The presence of advanced retinopathy, on the other hand, does not appear to influence the outcome. Patients Between January 1974 and December 1980, 44 renal transplants Introduction were performed in 40 diabetics with end-stage renal failure from diabetic nephropathy, and these have been followed up from 12 months Diabetic nephropathy is a common complication of long-term to six years.