The Do's and Don'ts of a Do-File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DC Console Using DC Console Application Design Software

DC Console Using DC Console Application Design Software DC Console is easy-to-use, application design software developed specifically to work in conjunction with AML’s DC Suite. Create. Distribute. Collect. Every LDX10 handheld computer comes with DC Suite, which includes seven (7) pre-developed applications for common data collection tasks. Now LDX10 users can use DC Console to modify these applications, or create their own from scratch. AML 800.648.4452 Made in USA www.amltd.com Introduction This document briefly covers how to use DC Console and the features and settings. Be sure to read this document in its entirety before attempting to use AML’s DC Console with a DC Suite compatible device. What is the difference between an “App” and a “Suite”? “Apps” are single applications running on the device used to collect and store data. In most cases, multiple apps would be utilized to handle various operations. For example, the ‘Item_Quantity’ app is one of the most widely used apps and the most direct means to take a basic inventory count, it produces a data file showing what items are in stock, the relative quantities, and requires minimal input from the mobile worker(s). Other operations will require additional input, for example, if you also need to know the specific location for each item in inventory, the ‘Item_Lot_Quantity’ app would be a better fit. Apps can be used in a variety of ways and provide the LDX10 the flexibility to handle virtually any data collection operation. “Suite” files are simply collections of individual apps. Suite files allow you to easily manage and edit multiple apps from within a single ‘store-house’ file and provide an effortless means for device deployment. -

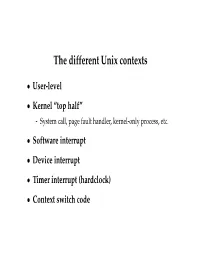

The Different Unix Contexts

The different Unix contexts • User-level • Kernel “top half” - System call, page fault handler, kernel-only process, etc. • Software interrupt • Device interrupt • Timer interrupt (hardclock) • Context switch code Transitions between contexts • User ! top half: syscall, page fault • User/top half ! device/timer interrupt: hardware • Top half ! user/context switch: return • Top half ! context switch: sleep • Context switch ! user/top half Top/bottom half synchronization • Top half kernel procedures can mask interrupts int x = splhigh (); /* ... */ splx (x); • splhigh disables all interrupts, but also splnet, splbio, splsoftnet, . • Masking interrupts in hardware can be expensive - Optimistic implementation – set mask flag on splhigh, check interrupted flag on splx Kernel Synchronization • Need to relinquish CPU when waiting for events - Disk read, network packet arrival, pipe write, signal, etc. • int tsleep(void *ident, int priority, ...); - Switches to another process - ident is arbitrary pointer—e.g., buffer address - priority is priority at which to run when woken up - PCATCH, if ORed into priority, means wake up on signal - Returns 0 if awakened, or ERESTART/EINTR on signal • int wakeup(void *ident); - Awakens all processes sleeping on ident - Restores SPL a time they went to sleep (so fine to sleep at splhigh) Process scheduling • Goal: High throughput - Minimize context switches to avoid wasting CPU, TLB misses, cache misses, even page faults. • Goal: Low latency - People typing at editors want fast response - Network services can be latency-bound, not CPU-bound • BSD time quantum: 1=10 sec (since ∼1980) - Empirically longest tolerable latency - Computers now faster, but job queues also shorter Scheduling algorithms • Round-robin • Priority scheduling • Shortest process next (if you can estimate it) • Fair-Share Schedule (try to be fair at level of users, not processes) Multilevel feeedback queues (BSD) • Every runnable proc. -

The Ifplatform Package

The ifplatform package Original code by Johannes Große Package by Will Robertson http://github.com/wspr/ifplatform v0.4a∗ 2017/10/13 1 Main features and usage This package provides the three following conditionals to test which operating system is being used to run TEX: \ifwindows \iflinux \ifmacosx \ifcygwin If you only wish to detect \ifwindows, then it does not matter how you load this package. Note then that use of (Linux or Mac OS X or Cygwin) can then be detected with \ifwindows\else. If you also wish to determine the difference between which Unix-variant you are using (i.e., also detect \iflinux, \ifmacosx, and \ifcygwin) then shell escape must be enabled. This is achieved by using the -shell-escape command line option when executing LATEX. If shell escape is not enabled, \iflinux, \ifmacosx, and \ifcygwin will all return false. A warning will be printed in the console output to remind you in this case. ∗Thanks to Ken Brown, Joseph Wright, Zebb Prime, and others for testing this package. 1 2 Auxiliary features \ifshellescape is provided as a conditional to test whether shell escape is active or not. (Note: new versions of pdfTEX allow you to query shell escape with \ifnum\pdfshellescape>0 , and the pdftexcmds package provides the wrapper \pdf@shellescape which works with X TE EX, pdfTEX, and LuaTEX.) Also, the \platformname command is defined to expand to a macro that represents the operating system. Default definitions are (respectively): \windowsname ! ‘Windows’ \notwindowsname ! ‘*NIX’ (when shell escape is disabled) \linuxname ! ‘Linux’ \macosxname ! ‘Mac OS X’ \cygwinname ! ‘Cygwin’ \unknownplatform ! whatever is returned by uname E.g., if \ifwindows is true then \platformname expands to \windowsname, which expands to ‘Windows’. -

Backup and Restore Cisco Prime Collaboration Provisioning

Backup and Restore Cisco Prime Collaboration Provisioning This section explains the following: • Perform Backup and Restore, page 1 • Back Up the Single-Machine Provisioning Database, page 2 • Restore the Single-Machine Provisioning Database, page 3 • Schedule Backup Using the Provisioning User Interface, page 5 Perform Backup and Restore Cisco Prime Collaboration Provisioning allows you to backup your data and restore it. You can schedule periodic backups using the Provisioning UI (Schedule Backup Using the Provisioning User Interface, on page 5). There are two backup and restore scenarios; select the set of procedures that matches your scenario: • Backup and restore on a single machine, with the same installation or a new installation. For this scenario, see Schedule Backup Using the Provisioning User Interface, on page 5. Note When backing up files, you should place the files on a different file server. Also, you should burn the backup data onto a CD. Cisco Prime Collaboration Provisioning allows you to back up system data and restore it on a different system in the event of total system failure. To restore the backup from another system, the following prerequisites must be met: • Ensure that the server to which data is restored has the same MAC address as that of the system that was backed up (the IP address and the hostname can be different). • If you are unable to assign the MAC address of the original system (the one that was backed up) to another system, contact the Engineering Team for information on a new license file (for a new MAC address). Cisco Prime Collaboration Provisioning Install and Upgrade Guide, 12.3 1 Backup and Restore Cisco Prime Collaboration Provisioning Back Up the Single-Machine Provisioning Database • The procedure to backup and restore data on a different system is the same as the procedure to backup and restore data on the same system. -

A First Course to Openfoam

Basic Shell Scripting Slides from Wei Feinstein HPC User Services LSU HPC & LON [email protected] September 2018 Outline • Introduction to Linux Shell • Shell Scripting Basics • Variables/Special Characters • Arithmetic Operations • Arrays • Beyond Basic Shell Scripting – Flow Control – Functions • Advanced Text Processing Commands (grep, sed, awk) Basic Shell Scripting 2 Linux System Architecture Basic Shell Scripting 3 Linux Shell What is a Shell ▪ An application running on top of the kernel and provides a command line interface to the system ▪ Process user’s commands, gather input from user and execute programs ▪ Types of shell with varied features o sh o csh o ksh o bash o tcsh Basic Shell Scripting 4 Shell Comparison Software sh csh ksh bash tcsh Programming language y y y y y Shell variables y y y y y Command alias n y y y y Command history n y y y y Filename autocompletion n y* y* y y Command line editing n n y* y y Job control n y y y y *: not by default http://www.cis.rit.edu/class/simg211/unixintro/Shell.html Basic Shell Scripting 5 What can you do with a shell? ▪ Check the current shell ▪ echo $SHELL ▪ List available shells on the system ▪ cat /etc/shells ▪ Change to another shell ▪ csh ▪ Date ▪ date ▪ wget: get online files ▪ wget https://ftp.gnu.org/gnu/gcc/gcc-7.1.0/gcc-7.1.0.tar.gz ▪ Compile and run applications ▪ gcc hello.c –o hello ▪ ./hello ▪ What we need to learn today? o Automation of an entire script of commands! o Use the shell script to run jobs – Write job scripts Basic Shell Scripting 6 Shell Scripting ▪ Script: a program written for a software environment to automate execution of tasks ▪ A series of shell commands put together in a file ▪ When the script is executed, those commands will be executed one line at a time automatically ▪ Shell script is interpreted, not compiled. -

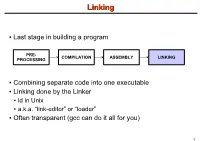

Linking + Libraries

LinkingLinking ● Last stage in building a program PRE- COMPILATION ASSEMBLY LINKING PROCESSING ● Combining separate code into one executable ● Linking done by the Linker ● ld in Unix ● a.k.a. “link-editor” or “loader” ● Often transparent (gcc can do it all for you) 1 LinkingLinking involves...involves... ● Combining several object modules (the .o files corresponding to .c files) into one file ● Resolving external references to variables and functions ● Producing an executable file (if no errors) file1.c file1.o file2.c gcc file2.o Linker Executable fileN.c fileN.o Header files External references 2 LinkingLinking withwith ExternalExternal ReferencesReferences file1.c file2.c int count; #include <stdio.h> void display(void); Compiler extern int count; int main(void) void display(void) { file1.o file2.o { count = 10; with placeholders printf(“%d”,count); display(); } return 0; Linker } ● file1.o has placeholder for display() ● file2.o has placeholder for count ● object modules are relocatable ● addresses are relative offsets from top of file 3 LibrariesLibraries ● Definition: ● a file containing functions that can be referenced externally by a C program ● Purpose: ● easy access to functions used repeatedly ● promote code modularity and re-use ● reduce source and executable file size 4 LibrariesLibraries ● Static (Archive) ● libname.a on Unix; name.lib on DOS/Windows ● Only modules with referenced code linked when compiling ● unlike .o files ● Linker copies function from library into executable file ● Update to library requires recompiling program 5 LibrariesLibraries ● Dynamic (Shared Object or Dynamic Link Library) ● libname.so on Unix; name.dll on DOS/Windows ● Referenced code not copied into executable ● Loaded in memory at run time ● Smaller executable size ● Can update library without recompiling program ● Drawback: slightly slower program startup 6 LibrariesLibraries ● Linking a static library libpepsi.a /* crave source file */ … gcc .. -

“Log” File in Stata

Updated July 2018 Creating a “Log” File in Stata This set of notes describes how to create a log file within the computer program Stata. It assumes that you have set Stata up on your computer (see the “Getting Started with Stata” handout), and that you have read in the set of data that you want to analyze (see the “Reading in Stata Format (.dta) Data Files” handout). A log file records all your Stata commands and output in a given session, with the exception of graphs. It is usually wise to retain a copy of the work that you’ve done on a given project, to refer to while you are writing up your findings, or later on when you are revising a paper. A log file is a separate file that has either a “.log” or “.smcl” extension. Saving the log as a .smcl file (“Stata Markup and Control Language file”) keeps the formatting from the Results window. It is recommended to save the log as a .log file. Although saving it as a .log file removes the formatting and saves the output in plain text format, it can be opened in most text editing programs. A .smcl file can only be opened in Stata. To create a log file: You may create a log file by typing log using ”filepath & filename” in the Stata Command box. On a PC: If one wanted to save a log file (.log) for a set of analyses on hard disk C:, in the folder “LOGS”, one would type log using "C:\LOGS\analysis_log.log" On a Mac: If one wanted to save a log file (.log) for a set of analyses in user1’s folder on the hard drive, in the folder “logs”, one would type log using "/Users/user1/logs/analysis_log.log" If you would like to replace an existing log file with a newer version add “replace” after the file name (Note: PC file path) log using "C:\LOGS\analysis_log.log", replace Alternately, you can use the menu: click on File, then on Log, then on Begin. -

FIFI-LS Highlights Robert Minchin FIFI-LS Highlights

FIFI-LS Highlights Robert Minchin FIFI-LS Highlights • Nice face-on galaxies where [CII] traces star formation [CII] traces star formation in M51 Pineda et al. 2018 [CII] in NGC 6946 Bigiel et al. 2020 [CII] particularly important as H2 & SFR tracer in inter-arm regions FIFI-LS Highlights • Nice face-on galaxies where [CII] traces star formation • Galaxies where [CII] doesn’t trace star formation [CII] from shocks & turbulence in NGC 4258 • [CII] seen along X-ray/radio ‘arms’ of NGC 4258, associated with past or present jet activity • [CII] excited by shocks and turbulence associated with the jet impacting the disk • NOT star formation Appleton et al. 2018 Excess [CII] in HE 1353-1917 1011 HE 1353-1917 1% MUSE RGB Images: 0.1 % • HE 1353-1917 1010 iband[OIII] Hα 0.02 % has a large 109 excess in HE 0433-1028 L[CII]/LFIR 8 10 excess 1σ 10 × 2σ /L 3C 326 3σ HE 1029-1831 • AGN ionization [CII] 7 10 HE 1108-2813 L cone intercepts HE 2211-3903 106 the cold SOFIA AGN Hosts galactic disk AGN Hosts High z 105 LINERs [Brisbin+15] Normal Galaxies LIRGs ULIRGs [Decarli+18] 104 108 109 1010 1011 1012 1013 1014 L /L Smirnova-Pinchukova et al. 2019 FIR Shock-excited [CII] in NGC 2445 [CII] in the ring of NGC 2445 is enhanced compared to PAHs, showing a shock excitement origin rather than star formation Fadda & Appleton, 2020, AAS Meeting 235 FIFI-LS Highlights • Nice face-on galaxies where [CII] traces star formation • Galaxies where [CII] doesn’t trace star formation • Galaxies with gas away from the plane Extraplanar [CII] in edge-on galaxies • Edge-on galaxies NGC 891 & NGC 5907 observed by Reach et al. -

21Files2.Pdf

Here is a portion of a Unix directory tree. The ovals represent files, the rectangles represent directories (which are really just special cases of files). A simple implementation of a directory consists of an array of pairs of component name and inode number, where the latter identifies the target file’s inode to the operating system (an inode is data structure maintained by the operating system that represents a file). Note that every directory contains two special entries, “.” and “..”. The former refers to the directory itself, the latter to the directory’s parent (in the case of the slide, the directory is the root directory and has no parent, thus its “..” entry is a special case that refers to the directory itself). While this implementation of a directory was used in early file systems for Unix, it suffers from a number of practical problems (for example, it doesn’t scale well for large directories). It provides a good model for the semantics of directory operations, but directory implementations on modern systems are more complicated than this (and are beyond the scope of this course). Here are two directory entries referring to the same file. This is done, via the shell, through the ln command which creates a (hard) link to its first argument, giving it the name specified by its second argument. The shell’s “ln” command is implemented using the link system call. Here are the (abbreviated) contents of both the root (/) and /etc directories, showing how /unix and /etc/image are the same file. Note that if the directory entry /unix is deleted (via the shell’s “rm” command), the file (represented by inode 117) continues to exist, since there is still a directory entry referring to it. -

Sleep 2.1 Manual

Sleep 2.1 Manual "If you put a million monkeys at a million keyboards, one of them will eventually write a Java program. The rest of them will write Perl programs." -- Anonymous Raphael Mudge Sleep 2.1 Manual Revision: 06.02.08 Released under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 License (see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/us/) You are free: • to Share -- to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work • to Remix -- to make derivative works Under the following conditions: Attribution. You must attribute this work to Raphael Mudge with a link to http://sleep.dashnine.org/ Share Alike. If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same, similar or a compatible license. • For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. The best way to do this is with a link to the license. • Any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder. • Apart from the remix rights granted under this license, nothing in this license impairs or restricts the author's moral rights. Your fair use and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................. 1 I. What is Sleep?...................................................................................................1 II. Manual Conventions......................................................................................2 III. -

The AWK Programming Language

The Programming ~" ·. Language PolyAWK- The Toolbox Language· Auru:o V. AHo BRIAN W.I<ERNIGHAN PETER J. WEINBERGER TheAWK4 Programming~ Language TheAWI(. Programming~ Language ALFRED V. AHo BRIAN w. KERNIGHAN PETER J. WEINBERGER AT& T Bell Laboratories Murray Hill, New Jersey A ADDISON-WESLEY•• PUBLISHING COMPANY Reading, Massachusetts • Menlo Park, California • New York Don Mills, Ontario • Wokingham, England • Amsterdam • Bonn Sydney • Singapore • Tokyo • Madrid • Bogota Santiago • San Juan This book is in the Addison-Wesley Series in Computer Science Michael A. Harrison Consulting Editor Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Aho, Alfred V. The AWK programming language. Includes index. I. AWK (Computer program language) I. Kernighan, Brian W. II. Weinberger, Peter J. III. Title. QA76.73.A95A35 1988 005.13'3 87-17566 ISBN 0-201-07981-X This book was typeset in Times Roman and Courier by the authors, using an Autologic APS-5 phototypesetter and a DEC VAX 8550 running the 9th Edition of the UNIX~ operating system. -~- ATs.T Copyright c 1988 by Bell Telephone Laboratories, Incorporated. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy ing, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Published simultaneously in Canada. UNIX is a registered trademark of AT&T. DEFGHIJ-AL-898 PREFACE Computer users spend a lot of time doing simple, mechanical data manipula tion - changing the format of data, checking its validity, finding items with some property, adding up numbers, printing reports, and the like. -

Parallel Processing Here at the School of Statistics

Parallel Processing here at the School of Statistics Charles J. Geyer School of Statistics University of Minnesota http://www.stat.umn.edu/~charlie/parallel/ 1 • batch processing • R package multicore • R package rlecuyer • R package snow • grid engine (CLA) • clusters (MSI) 2 Batch Processing This is really old stuff (from 1975). But not everyone knows it. If you do the following at a unix prompt nohup nice -n 19 some job & where \some job" is replaced by an actual job, then • the job will run in background (because of &). • the job will not be killed when you log out (because of nohup). • the job will have low priority (because of nice -n 19). 3 Batch Processing (cont.) For example, if foo.R is a plain text file containing R commands, then nohup nice -n 19 R CMD BATCH --vanilla foo.R & executes the commands and puts the printout in the file foo.Rout. And nohup nice -n 19 R CMD BATCH --no-restore foo.R & executes the commands, puts the printout in the file foo.Rout, and saves all created R objects in the file .RData. 4 Batch Processing (cont.) nohup nice -n 19 R CMD BATCH foo.R & is a really bad idea! It reads in all the objects in the file .RData (if one is present) at the beginning. So you have no idea whether the results are reproducible. Always use --vanilla or --no-restore except when debugging. 5 Batch Processing (cont.) This idiom has nothing to do with R. If foo is a compiled C or C++ or Fortran main program that doesn't have command line arguments (or a shell, Perl, Python, or Ruby script), then nohup nice -n 19 foo & runs it.