The Snows of Kilimanjaro 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hills Are Alive

18 ★ FTWeekend 2 May/3 May 2015 House Home perfect, natural columns of Ginkgo biloba“Menhir”. Pergolasandterraces,whichdripwith trumpet vine in summer, look down on standing stones and a massive “stone Returning to Innisfree after 15 years, Jane Owen henge”framingthelake. A grass dome, “possibly a chunk of mountain top or some such cast finds out whether this living work of art in down by the glacier that created the lake”, says Oliver, is echoed by clipped New York State retains its magic domes of Pyrus calleryana, the pear nativetoChina. Beyond the white pine woods, the path becomes boggy and narrow, criss- crossed with tree roots, moss and fungi. A covered wooden bridge reminds visi- torsthisisanall-Americanlandscape. Buteventheall-American,maplesyr- The hills up-supplying sugar maples here come with a twist. They are Acer saccharum “Monumentale” and, like the ginkgos, are naturally column-shaped. Innis- free’s American elms went years ago, are alive . victims of Dutch elm disease, but the Hemlocks are hanging on, with the help ofinsecticidetofightthewoollyadelgid. Larger garden pests include beavers, which have built a lodge 100m from the bout 90 miles west of the Iwillariseandgonow,andgoto bubble fountain, and deer. At least the thrumming heart of New Innisfree, . latter has a use, as part of a programme York City is a landscape Ihearlakewaterlappingwithlow of hunters donating food for those in that stirs my soul. I rate soundsbytheshore; need. So the dispossessed eat venison, it along with Villa Lante, WhileIstandontheroadway,oron albeitthetough,end-of-seasonsort. AThe Garden of Cosmic Speculation, thepavementsgrey, All is beautiful, but there’s one Liss Ard in Ireland, Little Sparta, Nin- Ihearitinthedeepheart’score. -

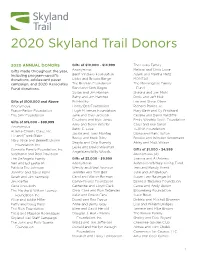

2020 Donor List

2020 Skyland Trail Donors 2020 ANNUAL DONORS Gifts of $10,000 - $14,999 The Lesko Family Gifts made throughout the year, Anonymous Melissa and Chris Lowe including program-specific Banfi Vintners Foundation Adam and Martha Metz donations, adolescent paver Libby and Brooks Barge MONTAG campaign, and 2020 Associates The Breman Foundation The Morningside Family Fund donations. Rand and Seth Hagen Fund Susan and Jim Hannan Shauna and Jim Muhl Patty and Jim Hatcher Doris and Jeff Muir Gifts of $100,000 and Above Ed Herlihy Lee and Steve Olsen Anonymous Honey Bee Foundation Richard Parker, Jr. Fraser-Parker Foundation Hugh M. Inman Foundation Mary Beth and Cy Pritchard The SKK Foundation Jane and Clay Jackson Cecelia and David Ratcliffe Courtney and Kyle Jenks Emily Winship Scott Foundation Gifts of $15,000 - $99,999 Amy and Nevin Kreisler Caryl and Ken Smith Anonymous Betts C. Love TEGNA Foundation Atlanta Charity Clays, Inc. Jackie and Tony Montag Diana and Mark Tipton Liz and Frank Blake Becky and Mark Riley Brooke and Winston Weinmann Mary Alice and Bennett Brown Shayla and Chip Rumely Abby and Matt Wilson Foundation, Inc. Leslie and David Wierman Connolly Family Foundation, Inc. Gifts of $1,000 - $4,999 Angela and Billy Woods Stephanie and Reid Davidson Anonymous (2) The DeAngelo Family Gifts of $5,000 - $9,999 Joanna and Al Adams Nan and Ed Easterlin Anonymous Ashmore-Whitney Giving Fund Patricia Toy Johnson Wendy and Neal Aronson Terri and Randy Avent Jennifer and David Kahn Jennifer and Tom Bell Julie and Jim Balloun Sarah and Jim Kennedy Carol and Walter Berman Susan Lare Baumgartel Jim Kieffer Camp-Younts Foundation Bennett Thrasher Foundation Carla Knobloch Catherine and Lloyd Clark Carrie and Andy Beskin The Martha & Wilton Looney Chris Cline and Ron Rezendes Bloomberg Foundation Foundation Inc. -

Scout Songs It Goes on and on My Friends

TAPS Day is done, Fading light, Thanks and Praise Opening Songs Gone the sun, dims the sight, For our days; From the lake, And a star ‘Neath the sun, From the hills, gems the sky ‘neath the stars, From the sky, gleaming bright. ‘neath the sky; All is well, safely rest, From afar, As we go, God is nigh. drawing nigh, This we know, fall the night. God is nigh. DAY CAMP CLOSING SONG (Tune: “Yankee Doodle”) And now it’s time to say goodbye, But we won’t feel so blue; ‘Cause soon the time will come again when we’ll be back to see you. Cub Scout day camp’s lots of fun—Games and crafts and singing, So get your pals and join the fun for a week filled to the brimming! SCOUT VESPERS WE’RE ALL TOGETHER AGAIN (Tune: O Tannenbaum) We’re all together again Softly falls the light of day, We’re here, we’re here As our campfire fades away; We’re all together again Silently each Scout should ask, We’re here, we’re here “Have I done my daily task? And who knows when Have I kept my honor bright? We’ll be all together again Can I guiltless sleep tonight? Signing all together again Have I done and have I dared, We’re here, we’re here Everything to be prepared?” 32 1 TAPS Day is done, Fading light, Thanks and Praise Opening Songs Gone the sun, dims the sight, For our days; From the lake, And a star ‘Neath the sun, From the hills, gems the sky ‘neath the stars, From the sky, gleaming bright. -

Path to Rome Walk May 8 to 20, 2018

Path to Rome Walk May 8 to 20, 2018 “A delight—great food and wine, beautiful countryside, lovely hotels and congenial fellow travelers with whom to enjoy it all.” —Alison Anderson, Italian Lakes Walk, 2016 RAVEL a portion of the Via Francigena, the pilgrimage route that linked T Canterbury to Rome in the Middle Ages, following its route north of Rome through olive groves, vineyards and ancient cypress trees. Discover the pleasures of Central Italy’s lesser-known cities, such as Buonconvento, Bolsena, Caprarola and Calcata. With professor of humanities Elaine Treharne as our faculty leader and Peter Watson as our guide, we refresh our minds, bodies and souls on our walks, during which we stop to picnic on hearty agrarian cuisine and enjoy the peace and quiet that are hallmarks of these beautiful rural settings. At the end of our meanderings, descend from the hills of Rome via Viale Angelico to arrive at St. Peter’s Basilica, the seat of Catholicism and home to a vast store of art treasures, including the Sistine Chapel. Join us! Faculty Leader Professor Elaine Treharne joined the Stanford faculty in 2012 in the School of Humanities and Sciences as a Professor of English. She is also the director of the Center for Spatial and Textual Analysis. Her main research focuses on early medieval manuscripts, Old and Middle English religious poetry and prose, and the history of handwriting. Included in that research is her current project, which looks at the materiality of textual objects, together with the patterns that emerge in the long history of text technologies, from the earliest times (circa 70,000 B.C.E.) to the present day. -

The Forests of Tuscany (Italy) in the Last Century

Article Forest Surface Changes and Cultural Values: The Forests of Tuscany (Italy) in the Last Century Francesco Piras, Martina Venturi *, Federica Corrieri, Antonio Santoro and Mauro Agnoletti Department of Agriculture, Food, Environment and Forestry (DAGRI), University of Florence, Via San Bonaventura 13, 50145 Florence, Italy; francesco.piras@unifi.it (F.P.); federica.corrieri@unifi.it (F.C.); antonio.santoro@unifi.it (A.S.); mauro.agnoletti@unifi.it (M.A.) * Correspondence: martina.venturi@unifi.it Abstract: Despite the definition of social and cultural values as the third pillar of Sustainable Forest Management (SFM) in 2003 and the guidelines for their implementation in SFM in 2007 issued by the Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forest in Europe (MCPFE), the importance of cultural values is not sufficiently transferred into forest planning and conservation. Tuscany is widely known for the quality of its cultural landscape, however, the abandonment of agro-pastoral surfaces as a consequence of rural areas depopulation, has led to widespread reforestation and to the abandonment of forest management. In addition, due to the interruption of a regular forest management and to the fact that most of the population lives in cities, forests are no more perceived as part of the cultural heritage, but mainly as a natural landscape. Due to this trend traditional forest management techniques, such as coppicing, have also been considered as a factor of degradation Citation: Piras, F.; Venturi, M.; and not even a historical management form. The aim of the study is therefore to analyze forest Corrieri, F.; Santoro, A.; Agnoletti, M. surface changes in Tuscany in the last century to assess the importance of cultural values. -

Evaluating the Effects of the Geography of Italy Geography Of

Name: Date: Evaluating the Effects of the Geography of Italy Warm up writing space: Review: What are some geographical features that made settlement in ancient Greece difficult? Write as many as you can. Be able to explain why you picked them. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________________ Give One / Get One Directions: • You will get 1 card with important information about Rome’s or Italy’s geography. Read and understand your card. • Record what you learned as a pro or a con on your T chart. • With your card and your T chart, stand up and move around to other students. • Trade information with other students. Explain your card to them (“Give One”), and then hear what they have to say (“Get One.”) Record their new information to your T chart. • Repeat! Geography of Italy Pros J Cons L Give one / Get one cards (Teachers, preprint and cut a set of these cards for each class. If there are more than 15 students in a class, print out a few doubles. It’s okay for some children to get the same card.) The hills of Rome Fertile volcanic soil 40% Mountainous The city-state of Rome was originally Active volcanoes in Italy (ex: Mt. About 40% of the Italian peninsula is built on seven hills. Fortifications and Etna, Mt. Vesuvius) that create lava covered by mountains. important buildings were placed at and ash help to make some of the the tops of the hills. Eventually, a land on the peninsula more fertile. city-wall was built around the hills. Peninsula Mediterranean climate Tiber River Italy is a narrow peninsula—land Italy, especially the southern part of The Tiber River links Rome, which is surrounded by water on 3 sides. -

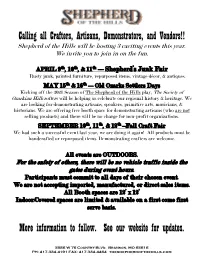

Calling All Crafters, Artisans, Demonstrators, and Vendors!! More Information to Follow. See Our Website for Updates

Calling all Crafters, Artisans, Demonstrators, and Vendors!! Shepherd of the Hills will be hosting 3 exciting events this year. We invite you to join in on the fun. APRIL 9th, 10th, & 11th —Shepherd’s Junk Fair Rusty junk, painted furniture, repurposed items, vintage décor, & antiques. MAY 15th & 16th —Old Ozarks Settlers Days Kicking off the 2021 Season of The Shepherd of the Hills play, The Society of Ozarkian Hillcrofters will be helping us celebrate our regional history & heritage. We are looking for demonstrating artisans, speakers, primitive arts, musicians, & historians. We are offering free booth space for demonstrating artisans (who are not selling products) and there will be no charge for non-profit organizations. SEPTEMBER 10th, 11th, & 12th –Fall Craft Fair We had such a successful event last year, we are doing it again! All products must be handcrafted or repurposed items. Demonstrating crafters are welcome. All events are OUTDOORS. For the safety of others, there will be no vehicle traffic inside the gates during event hours. Participants must commit to all days of their chosen event. We are not accepting imported, manufactured, or direct sales items. All Booth spaces are 12’ x 12’ Indoor/Covered spaces are limited & available on a first come first serve basis. More information to follow. See our website for updates. 5586 W 76 Country Blvd. Branson, MO 65616 PH: 417.334.4191 FAX: 417.334.4464 theshepherdofthehills.com 2021 Vendor Request for Space Early Application ~Circle chosen event(s)~ Shepherd’s Junk Fair Old Ozarks -

Teaching Music Through Performance in Band

Teaching Music through Performance in Band A Comprehensive Listing of All Volumes by Grade, 2018 Band, volumes 1 (2nd ed.)–11 Beginning Band, volumes 1–2 Middle School Band Marches GIA Publications, Inc. Contents Core Components . 4 Through the Years with the Teaching Music Series . 5 Band, volumes 1 (2nd ed .)–11 . .. 6 Beginning Band, volumes 1–2 . 30 Middle School Band . 33 Marches . .. 36 Core Components The Books Part I presents essays by the leading lights of instrumental music education, written specifically for the Teaching Music series to instruct, inform, enlighten, inspire, and encourage music directors in their daily tasks . Part II presents Teacher Resource Guides that provide practical, detailed reference to the best-known and foundational band compositions, Grades 2–6,* and their composers . In addition to historical background and analysis, music directors will find insight and practical guidance for streamlining and energizing rehearsals . The Recordings North Texas Wind Symphony Internationally acknowledged as one of the premier ensembles of its kind, the North Texas Wind Symphony is selected from the most outstanding musicians attending the North Texas College of Music . The ensemble pursues the highest pro- fessional standards and is determined to bring its audiences exemplary repertoire from all musical periods, cultures, and styles . Eugene Migliaro Corporon Conductor of the Wind Symphony and Regents Professor of Music at the University of North Texas, Eugene Corporon also serves as the Director of Wind Studies, guiding all aspects of the program . His performances have drawn praise from colleagues, composers, and critics alike . His ensembles have performed for numerous conventions and clinics across the world, and have recorded over 600 works featured on over 100 recordings . -

Download Itinerary

London to Paris Cycle UK & FRANCE Activity: Cycle Grade: 1 Challenging Duration: 5 Days ycling from London to Paris is one of strenuous hill-climbs, the sight of the Eif- CHALLENGE GRADING Cthe great cycle experiences in Europe. fel Tower, our finishing point, will evoke a Passing through picturesque Kent coun- real sense of achievement. Our trips are graded from Challenging (Grade 1) to tryside, we cross the Channel and con- Extreme (Grade 5). tinue through the small villages and me- Our last day in Paris allows us to explore This ride is graded Challenging (1). Main chal- dieval market towns of Northern France. the sights and soak up the romantic at- lenges lie in the long distances (70-100 miles) With long days in the saddle and some mosphere of this majestic city! with undulating terrain, including some short, sharp climbs. Many factors influence the Challenge Grading, such as terrain, distances, climate, altitude, living conditions, etc. The grade reflects the overall trip; This was my first time on a Discover Adventure trip, and I’m some sections will feel more challenging than “ others. Unusual weather conditions also have a sure it won’t be my last! - Helen significant impact, and not all people are tested by the same aspects. Our grading levels are intended as a guide, but span a broad spectrum; trips within the same grade will still vary in the level of challenge provided. DETAILED ITINERARY Day 1: London – Dover – Dunkirk An early start allows us to avoid the morning traffic as we pass through the outskirts of London onto quieter roads. -

Hawaiian Plant Studies 14 1

The History, Present Distribution, and Abundance of Sandalwood on Oahu, Hawaiian Islands: . Hawaiian Plant Studies 14 1 HAROLD ST. JOHN 2 INTRODUCTION album L., the species first commercialized, TODAY IT IS a common belief of the resi is now considered to have been introduced dents of the Hawaiian Islands that the san into India many centuries ago and cultivated dalwood tree was exterminated during the there for its economic and sentimental val sandalwood trade in the early part of the ues. Only in more recent times has it at . nineteenth century and that it is now ex tained wide distribution and great abun tinct on the islands. To correct this impres dance in that country. It is certainly indige sion, the following notes are presented.. nous in Timor and apparently so all along There is a popular as well as a scientific the southern chain of the East Indies to east interest in the sandalwood tree or iliahi of ern Java, including the islands of Roti, We the Hawaiians, the fragrant wood of which tar, Sawoe, Soemba, Bali, and Madoera. The was the first important article of commerce earliest voyagers found it on those islands exported from the Hawaiian Islands. and it was early an article of export, reach For centuries the sandalwood, with its ing the markets of China and India (Skotts pleasantly fragrant dried heartwood, was berg, 1930: 436; Fischer, 1938). The in much sought for. In the Orient, particularly sufficient and diminishing supply of white in China, Burma, and India, the wood was sandalwood gave it a very high and increas used for the making of idols and sacred ing value.' Hence, trade in the wood was utensils for shrines, choice boxes and carv profitable even when a long haul was in ings, fuel for funeral pyres, and joss sticks volved. -

Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide

TABLE OF CONTENTS The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway Guide INTRODUCTION . .2 1 CONEY ISLAND . .3 2 OCEAN PARKWAY . .11 3 PROSPECT PARK . .16 4 EASTERN PARKWAY . .22 5 HIGHLAND PARK/RIDGEWOOD RESERVOIR . .29 6 FOREST PARK . .36 7 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK . .42 8 KISSENA-CUNNINGHAM CORRIDOR . .54 9 ALLEY POND PARK TO FORT TOTTEN . .61 CONCLUSION . .70 GREENWAY SIGNAGE . .71 BIKE SHOPS . .73 2 The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway System ntroduction New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (Parks) works closely with The Brooklyn-Queens the Departments of Transportation Greenway (BQG) is a 40- and City Planning on the planning mile, continuous pedestrian and implementation of the City’s and cyclist route from Greenway Network. Parks has juris- Coney Island in Brooklyn to diction and maintains over 100 miles Fort Totten, on the Long of greenways for commuting and Island Sound, in Queens. recreational use, and continues to I plan, design, and construct additional The Brooklyn-Queens Greenway pro- greenway segments in each borough, vides an active and engaging way of utilizing City capital funds and a exploring these two lively and diverse number of federal transportation boroughs. The BQG presents the grants. cyclist or pedestrian with a wide range of amenities, cultural offerings, In 1987, the Neighborhood Open and urban experiences—linking 13 Space Coalition spearheaded the parks, two botanical gardens, the New concept of the Brooklyn-Queens York Aquarium, the Brooklyn Greenway, building on the work of Museum, the New York Hall of Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux, Science, two environmental education and Robert Moses in their creations of centers, four lakes, and numerous the great parkways and parks of ethnic and historic neighborhoods. -

22Nd Annual Florida Chapter Meet Howey in the Hills, Fl November 19

22nd Annual Florida Chapter Meet Howey in the Hills, Fl November 19-20, 2010 Please join us for our annual Fall Chapter judging meet at the beautiful 4 star rated Mission Inn Resort in Howey in the Hills,Florida. This annual event has been an excellent opportunity for people to bring their cars to be judged for the first time and an excellent opportunity to expand your judging skills. Judging is only open to current membership of National organization with preference being given to chapter members. The field will be limited to the first 12 pre- registered vehicles by October 1st to give us ample time to assemble the necessary quality judging teams.. Depending on judging capabilities of registered judges we will judge all classes. Free meet registration for the event judges. The Mission Inn has a block of rooms reserved for the participants and you may reserve yours by calling 1-800-874-9053 the room rate for the event is $145.00 + tax and the block will be released by October 15th. Schedule of Events Meet Registration Fee $25.00 Friday November 19th Arrive Friday afternoon Fl Chapter Membership $10.00 Dinner at Mission Inn on your own Saturday November 20th National Dues (New Member only) $31.00 Registration opens 8:00 AM Judges Meeting 8:30 AM Flight Judging $25.00 Flight Judging 9:00 AM to finish Awards 4:00 PM Sportsman Display $10.00 Chapter Meeting 5:00 PM Dinner @ Knickers 7:30 PM (Prime Rib & Seafood Buffet) Please register as early as possible for this event Mission Inn web site is www.missioninnresort.com .