The Obama Administration and the War on Terror

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strange Bedfellows: Network Neutrality‘S Unifying Influence†

STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: NETWORK NEUTRALITY‘S UNIFYING INFLUENCE† Marvin Ammori* I want to talk about something called network (or ―net‖) neutrality. Let me begin, though, with a story involving short codes. For those unfamiliar with what a short code is, recall the voting process on American Idol and the little code that you can punch into your cell phone to vote for your favorite singer.1 Short codes are not ten digit numbers; rather, they are more like five or six.2 In theory, anyone can get a short code. Presidential candidates use short codes in their campaigns to communicate with their followers. For instance, a person could have signed up and Barack Obama would have sent them a message through a short code when he chose Joe Biden as his running mate.3 A few years ago, an abortion rights group called NARAL Pro-Choice America wanted a short code to communicate with its own followers.4 NARAL‘s goal was not to send ―spam‖; instead, the short code was directed to people who agreed with their message.5 Verizon rejected the idea of a short code for this group because, according to Verizon, NARAL was engaged in ―controversial‖ speech. The New York Times printed a front page article about this.6 Many people who read the story wondered if they really needed a permission slip from Verizon, or from anyone else, to communicate about political things that they care about. In response † This speech is adapted for publication and was originally presented at a panel discussion as part of the Regent University Law Review and The Federalist Society for Law & Public Policy Studies Media and Law Symposium at Regent University School of Law, October 9–10, 2009. -

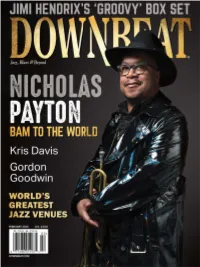

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

US Citizens As Enemy Combatants

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 18 Issue 2 Volume 18, Spring 2004, Issue 2 Article 14 U.S. Citizens as Enemy Combatants: Indication of a Roll-Back of Civil Liberties or a Sign of our Jurisprudential Evolution? Joseph Kubler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. U.S. CITIZENS AS ENEMY COMBATANTS; INDICATION OF A ROLL-BACK OF CIVIL LIBERTIES OR A SIGN OF OUR JURISPRUDENTIAL EVOLUTION? JOSEPH KUBLER I. EXTRAORDINARY TIMES Exigent circumstances require our government to cross legal boundaries beyond those that are unacceptable during normal times. 1 Chief Justice Rehnquist has expressed the view that "[w]hen America is at war.., people have to get used to having less freedom."2 A tearful Justice Sandra Day O'Connor reinforced this view, a day after visiting Ground Zero, by saying that "we're likely to experience more restrictions on our personal freedom than has ever been the case in our country."3 However, extraordinary times can not eradicate our civil liberties despite their call for extraordinary measures. "Lawyers have a special duty to work to maintain the rule of law in the face of terrorism, Justice O'Connor said, adding in a quotation from Margaret 1 See Christopher Dunn & Donna Leiberman, Security v. -

ACLU BLC, Orlando June 12, 2011

ACLU BLC, Orlando June 12, 2011 “Taking Liberties: The ACLU and the War on Terror” During the first week of September 2001, the ACLU got a new Executive Director for the first time in over 20 years. Anthony Romero began work in our current building at 125 Broad Street in downtown Manhattan, a building the ACLU had been occupying for only a few years, having moved down from the Roger Baldwin building on West 43rd Street, in midtown Manhattan, in 1997. During the second week of that month, I don’t need to tell you that downtown Manhattan was devastated, New York City changed, the country changed, and the world changed. And so the ACLU staff, including our new ED, faced all sorts of challenges in adapting to living and working in this new, uncomfortable physical and psychological environment: how do you meet the payroll when everything you need is locked into a building you’re not allowed to enter, and how do you answer a swarm of press inquiries when, in those pre-iPhone days, the computers and telephone systems were inaccessible? One of Anthony’s first tasks was to arrange psychological counseling for some staff members who were traumatized by being so close to the World Trade Center on 9/11 and afterwards. And the entire organization faced the equally daunting challenge of evaluating and responding to the government’s responses to 9/11. By the end of October, less than six weeks after the events of 9/11, Congress had enacted the USA PATRIOT Act which, I will remind you, was an acronym, standing for Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools for Intercepting and Obstructing Terrorism. -

Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics with Taylor Branch

Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics with Taylor Branch 2009 Table of Contents History of the Theodore H. White Lecture .........................................................5 Biography of Taylor Branch ..................................................................................7 Biographies of Nat Hentoff and David Nyhan ..................................................9 Welcoming Remarks by Dean David Ellwood ................................................11 Awarding of the David Nyhan Prize for Political Journalism to Nat Hentoff ................................................................................................11 The 2009 Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics “Disjointed History: Modern Politics and the Media” by Taylor Branch ...........................................................................................18 The 2009 Theodore H. White Seminar on Press and Politics .........................35 Alex S. Jones, Director of the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy (moderator) Dan Balz, Political Correspondent, The Washington Post Taylor Branch, Theodore H. White Lecturer Elaine Kamarck, Lecturer in Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School Alex Keyssar, Matthew W. Stirling Jr. Professor of History and Social Policy, Harvard Kennedy School Renee Loth, Columnist, The Boston Globe Twentieth Annual Theodore H. White Lecture 3 The Theodore H. White Lecture com- memorates the life of the reporter and historian who created the style and set the standard for contemporary -

His Prophecy Has Proven Accurate; the Post- 1914 Years Have Been an Era of Total War and the Total State

1 2 During World War I, American activist Randolph Bourne had warned, "War is the health of the State."1 His prophecy has proven accurate; the post- 1914 years have been an era of total war and the total state. It had seemed that with the fall of the Soviet Union, the state of permanent war, permanent mobilization, and permanent emergency would end. This hope has not been realized. Instead, the US and the world are now laying the groundwork for high-tech totalitarianism; liberty is in retreat, just as occurred almost everywhere between 1914 and 1945. Precedents from the 1790s through World War II Federal power grabs have been a bi-partisan policy, long before the War on Terror. All of these acts have created precedents for what is being done or proposed now. In 1798, the Federal Government passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, in response to the threat of war with France.2 "The Sedition Act made it a criminal offense to print or publish false, malicious, or scandalous statements directed against the U.S. government, the president, or Congress; to foster opposition to the lawful acts of Congress; or to aid a foreign power in plotting against the United States."3 About 25 people were arrested under the law, and 10 were imprisoned. The Sedition Act had an 1801 expiration date, and appeared to be designed to impede opposition party political activity and journalism in the 1800 Presidential election. These laws were unpopular, and the reaction to them helped win the 1800 election for Thomas Jefferson. -

Aliss/IPS/RL U.S

NATIONAL SECURITY PROJECT AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION December 9,2008 Deborah Waller, Paralegal Specialist Office ofthe Inspector General Department ofJustice 950 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Room 4726 Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 FOIAIPA Mail Referral Unit AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION Department ofJustice NATIONAL OFFICE Room 115 125 BROAD STREET, 18TH FL. NEW YORK, NY 10004-2400 LOC Building T/ 2 12. 54 9.2500 Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 WWW.ACLU.ORG OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS Elizabeth Farris, SUSAN N. HERMAN PRESIOENT Supervisory Paralegal Office ofLegal Counsel ANTHONY D. ROMERO EXECUTIVE OIRECTOR Room 5515,950 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Department ofJustice RICHARD ZACKS TREASURER Washington, DC 20530-0001 Information Officer Office ofFreedom ofInformation and Security Review Directorate for Executive Services and Communications FOIA/Privacy Branch 1155 Defense Pentagon, Room 2C757 Washington, D.C. 20301-1155 Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, D.C. 20505 Office ofInformation Programs and Services AlISS/IPS/RL U.S. Department ofState Washington, D.C. 20522-8100 Re: REQUEST UNDER FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT / Expedited Processing Requested Attention: This letter constitutes a request ("Request") pursuant to the Freedom ofInformation Act ("FOIA"), 5 U.S.C. § 552 et seq., the Department ofDefense implementing regulations, 32 C.F.R. § 286.1 et seq., the Department ofJustice implementing regulations, 28 C.F.R. § 16.1 et seq., the Department ofState implementing regulations, 22 C.F.R. § 171.1 et seq.,and the Central Intelligence Agency implementing regulations, 32 C.F.R. § 1900.1 et seq. The Request is submitted by the American Civil Liberties Union Foundation and the American Civil Liberties Union (collectively, the "ACLU,,).l AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION I. -

Marauding Youth and the Christian Front 233

S.H. Norwood: Marauding Youth and the Christian Front 233 Marauding Youth and the Christian Front: Antisemitic Violence in Boston and New York During World War II STEPHEN H. NORWOOD In October 1943, the New York newspaper PM declared that bands of Irish Catholic youths, inspired by the Coughlinite Christian Front, had for over a year waged an “organized campaign of terrorism” against Jews in Boston’s Dorchester district and in neighboring Roxbury and Mattapan. They had violently assaulted Jews in the streets and parks, often inflicting serious injuries with blackjacks and brass knuckles, and had desecrated synagogues and vandalized Jewish stores and homes. The New York Post stated that the “beatings of Jews” in Boston were “an almost daily occurrence.” State Senator Maurice Goldman, representing 100,000 Jews, residing mostly in Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan, joined by four state representatives from those areas, declared to Governor Leverett Saltonstall that their constituents were living “in mortal fear.” Many Jews could not leave their homes, even in daylight, frightened of being beaten by youths from adjacent Irish Catholic neighborhoods like South Boston, Fields Corner, and the Codman Square area, who deliberately entered Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan to go “Jew hunting.” The New York Yiddish daily The Day called the antisemitic violence that had occurred in Dorchester during the previous year “a series of small pogroms.”1 Neither Boston’s police nor its Catholic clergy made any serious effort to discourage the antisemitic -

The Making of the Red Hot Jazz Archive Would Have Been

Information About The Red Hot Archive The making of The Red Hot Jazz Archive would have been impossible without the incredible work of Jazz writers, historians and record collectors who did the original research, interviews and compiling of discographies that were used to assemble this web site. Below you will find some of the books that I found to be invaluable in compiling the information contained in these pages. Jazz Records 1897 - 1942 by Brian A. L. Rust Who's Who Of Jazz by John Chilton The Baby Dodds Story as told to Larry Gara Hear Me Talkin' To Ya The Story Of Jazz As Told By The Men Who Made It by Nat Shapiro and Nat Hentoff Really The Blues by Mezz Mezzrow and Bernard Wolfe With Louis And The Duke by Barney Bigard, edited by Barry Martyn In Search of Buddy Bolden by Donald M. Marquis Bix; Man And Legend, by Richard M. Sudhalterr and Philip R. Evans, Arlington House Publishers, 1974 New Orleans Jazz: A Revised History by R. Collins Chicago Jazz by William Howland Kenney From Cakewalks to Concert Halls An Illustrated History of African American Popular Music from 1895 to 1930 by Thomas L. Morgan http://www.redhotjazz.com/info.html (1 of 3)6/21/2005 3:30:43 PM Information About The Red Hot Archive From Jazz to Swing African-American Jazz Musicians And Their Music 1890-1935 by Thomas J. Hennessey Jazz: A History Of The New York Scene by Samuel B. Charters and Leonard Kunstadt Jelly Roll, Bix and Hoagy : Gennett Studios and the birth of recorded jazz by Rick Kennedy "Why would anyone be interested in those old things?" - Jelly Roll Morton Many people have asked if the Red Hot Jazz Archive is legal? The answer appears to be yes, but several experts have said that it falls into a gray area of law, concerning the transmission of the temporary Real Audio file and if that constitutes copying and distributing of the recordings. -

Strategy for the Black Struggle/16 Prospects for Labor's

MARCH 22, 1974 25 CENTS VOLUME 38/NUMBER 11 ·<' A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE New Hoover memos ·. _: ._ :::;.:~:=. Latest FBI memos detail gov't plan to destroy Black movement and prevent demonstrations like this Harlem protest against AHica massacre. For documents and analysis, see pages 3-5. Why an independent Black party: strategy for the Black struggle/16 Prospects for labor's fight against rising prices and unemployment/10 In Brief UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA CHILD-CARE FIGHT: 'No' on the Farm Workers." One hundred and fifty people rallied at the University Sam Baca, director of the UFW boycott in Detroit, THIS of Minnesota March 7 to demand that the administra likened the actions of the Teamsters to the strong-arm tion fund an on-campus child-care center for 60 children tactics they used to break UFW contracts in California. to open next fall. While saying that Mayor Young's decision not to en .WEEK'S Speakers focused on child care as a right, not a pnvl dorse the boycott was "setting a dangerous precedent," lege, and called on the administration to stop hedging Baca went on to say, "We're not implying a break with MILITANT and provide the ne~ded funds. Young." 6 A 'subversive' gets his Waving picket signs, singing, and chanting, "Child care HISC file now!" and "We will not stay home!" the group marched ANTI-ZIONISTS CONVICTED AND FINED: Last Oct. across campus to the administration building, where a 14, during the Mideast war, pro-Zionist forces in New 7 Houston cops admit infil spirited picket line demanded a public hearing on the York City organized a demonstration at city hall in sup tration of SWP child-care proposals being developed for the regents to port of the Israeli aggression. -

Subject: : 4A Issue From: Brett M. Kavanaugh ( CN=Brett M

: 4A issue Subject: : 4A issue From: Brett M. Kavanaugh ( CN=Brett M. Kavanaugh/OU=WHO/O=EOP [ WHO ] ) Date: 9/17/01, 7:28 AM To: "Yoo, John C" <[email protected]> ( "Yoo, John C" <[email protected]> [ UNKNOWN ] ) BCC: timothy flanigan ( timothy flanigan [ WHO ] ) ###### Begin Original ARMS Header ###### RECORD TYPE: PRESIDENTIAL (NOTES MAIL) CREATOR:Brett M. Kavanaugh ( CN=Brett M. Kavanaugh/OU=WHO/O=EOP [ WHO ] ) CREATION DATE/TIME:17-SEP-2001 07:28:35.00 SUBJECT:: 4A issue TO:"Yoo, John C" <[email protected]> ( "Yoo, John C" <[email protected]> [ UNKNOWN ] ) READ:UNKNOWN BCC:timothy flanigan ( timothy flanigan [ WHO ] ) READ:UNKNOWN ###### End Original ARMS Header ###### Any results yet on the 4A implications of random/constant surveillance of phone and e-mail conversations of non-citizens who are in the United States when the purpose of the surveillance is to prevent terrorist/criminal violence? epic.org EPIC-18-08-01-NARA-FOIA-20181218-Kavanaugh-Emails-Patriot-Act-Surveillance 000001 : Subject: : From: Brett M. Kavanaugh ( CN=Brett M. Kavanaugh/OU=WHO/O=EOP [ WHO ] ) Date: 5/20/02, 3:23 PM To: Kristen Silverberg ( CN=Kristen Silverberg/OU=WHO/O=EOP@EOP [ WHO ] ) ###### Begin Original ARMS Header ###### RECORD TYPE: PRESIDENTIAL (NOTES MAIL) CREATOR:Brett M. Kavanaugh ( CN=Brett M. Kavanaugh/OU=WHO/O=EOP [ WHO ] ) CREATION DATE/TIME:20-MAY-2002 15:23:32.00 SUBJECT:: TO:Kristen Silverberg ( CN=Kristen Silverberg/OU=WHO/O=EOP@EOP [ WHO ] ) READ:UNKNOWN ###### End Original ARMS Header ###### Confirmed that nothing re Customs Service searching mail in USA Patriot Act. -

ARE THERE ANY GOOD BOOKS on CIVIL LIBERTIES?

ARE THERE ANY GOOD BOOKS on CIVIL LIBERTIES? A Reader’s Guide * By Sam Walker THE PURPOSE OF THIS GUIDE Civil liberties is an important, fascinating and extremely complex subject. There are many, many books and articles on each and every topic: free speech, lesbian and gay rights, the war on terror, and so on. The abundance of material poses a serious problem for the person who is just learning about civil liberties, or who wants to read something on a topic where he or she has no background. Where to begin? This Guide is designed to provide an introduction to the best books on civil liberties issues. For each issue it begins by identifying a “Best First Book.” For each book there is a short discussion of how it approaches the topic and why it is such a good book. The books have been selected because they are well-written and will be of interest to the reader with no background on the topic. The Guide then suggests one or more other books for “Further Reading” and for readers interested in “Digging Deeper.” Most of these are longer more scholarly books. Let’s say you are interested in the Scopes Monkey trial. The Guide recommends Ray Ginger’s Six Days or Forever as the Best First Book and then Edward Larson’s longer more analytical books as Further Reading. To supplement the books, the Guide includes a “Film Fun” section recommending movies or video documentaries on the topic. For the Scopes case it recommends the Hollywood film Inherit the Wind, with a discussion of the ways it presents both a very accurate picture of parts of the trial and distorts the history of the case.