Marauding Youth and the Christian Front 233

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strange Bedfellows: Network Neutrality‘S Unifying Influence†

STRANGE BEDFELLOWS: NETWORK NEUTRALITY‘S UNIFYING INFLUENCE† Marvin Ammori* I want to talk about something called network (or ―net‖) neutrality. Let me begin, though, with a story involving short codes. For those unfamiliar with what a short code is, recall the voting process on American Idol and the little code that you can punch into your cell phone to vote for your favorite singer.1 Short codes are not ten digit numbers; rather, they are more like five or six.2 In theory, anyone can get a short code. Presidential candidates use short codes in their campaigns to communicate with their followers. For instance, a person could have signed up and Barack Obama would have sent them a message through a short code when he chose Joe Biden as his running mate.3 A few years ago, an abortion rights group called NARAL Pro-Choice America wanted a short code to communicate with its own followers.4 NARAL‘s goal was not to send ―spam‖; instead, the short code was directed to people who agreed with their message.5 Verizon rejected the idea of a short code for this group because, according to Verizon, NARAL was engaged in ―controversial‖ speech. The New York Times printed a front page article about this.6 Many people who read the story wondered if they really needed a permission slip from Verizon, or from anyone else, to communicate about political things that they care about. In response † This speech is adapted for publication and was originally presented at a panel discussion as part of the Regent University Law Review and The Federalist Society for Law & Public Policy Studies Media and Law Symposium at Regent University School of Law, October 9–10, 2009. -

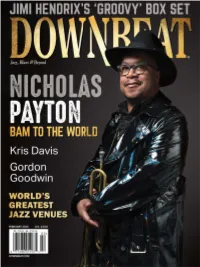

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

News Briefs the Elite Runners Were Those Who Are Responsible for Vive

VOL. 117 - NO. 16 BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, APRIL 19, 2013 $.30 A COPY 1st Annual Daffodil Day on the MARATHON MONDAY MADNESS North End Parks Celebrates Spring by Sal Giarratani Someone once said, “Ide- by Matt Conti ologies separate us but dreams and anguish unite us.” I thought of this quote after hearing and then view- ing the horrific devastation left in the aftermath of the mass violence that occurred after two bombs went off near the finish line of the Boston Marathon at 2:50 pm. Three people are reported dead and over 100 injured in the may- hem that overtook the joy of this annual event. At this writing, most are assuming it is an act of ter- rorism while officials have yet to call it such at this time 24 hours later. The Ribbon-Cutting at the 1st Annual Daffodil Day. entire City of Boston is on (Photo by Angela Cornacchio) high alert. The National On Sunday, April 14th, the first annual Daffodil Day was Guard has been mobilized celebrated on the Greenway. The event was hosted by The and stationed at area hospi- Friends of the North End Parks (FOTNEP) in conjunction tals. Mass violence like what with the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway Conservancy and North we all just experienced can End Beautification Committee. The celebration included trigger overwhelming feel- ings of anxiety, anger and music by the Boston String Academy and poetry, as well as (Photo by Andrew Martorano) daffodils. Other activities were face painting, a petting zoo fear. Why did anyone or group and a dog show held by RUFF. -

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Yektan Turkyilmaz 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the conflict in Eastern Anatolia in the early 20th century and the memory politics around it. It shows how discourses of victimhood have been engines of grievance that power the politics of fear, hatred and competing, exclusionary -

Extensions of Remarks

27328 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS October 9, 1987 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS ADL HELPS BLACK-JEWISH black/Jewish problem; it's a problem of big greater care and humanitarian treatment by COOPERATION otry." Israel <as well as the U.S.) is something we When pressed to say whether the group felt we should address," said Bachrach. would issue a statement about Farrakhan "We met with the editor of the largest HON. BARNEY FRANK <who spoke in Boston last weekend), delega Palestinian newspaper and could under OF MASSACHUSETTS tion coleader Rev. Charles Stith of Boston's stand his feelings about the right of self-de IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Union United Methodist Church and na termination-not a minor concern for any of tional president of the newly-formed Orga us. It was by no means an Israel cheerlead Friday, October 9, 1987 nization for a New Equality <O.N.E.) said, ing mission." Mr. FRANK. Mr. Speaker, under the leader "It is important to speak cogently and clear The group was struck by the complexity ship of Executive Director Leonard Zakim and ly on any issues of racism. But not to create and multi-sided nature of many of Israel's a flashpoint where there is none. He's been problems-from the status of the Black He such committee chairmen as Richard Glovsky saying what he's saying for thirty years." brews to the West Bank-but came away and Richard Morningstar, the New England re "The real strength of black/Jewish rela with a great deal of hope. gional office of the Anti-Defamation League of tions is in the communities where we are "It's important to realize that Israel is B'nai B'rith has done outstanding work in a working together," said Zakim. -

Truro Log August 2012 Truro Council on Aging

TRURO LOG AUGUST 2012 TRURO COUNCIL ON AGING WWW.TRURO-MA.GOV/COA William “Bill” Worthington explained to me the reason that he volunteers is because of the example of his parents. In the 60’s his father inherited some money and with it he built the Pamet Harbor Yacht Club and the floats. He bought a power launch, too. He and Charlie Francis also built the small house nearby. He got some boats and hired someone to teach sailing. Harriet Hobbs was one of the first students. Bill remembers that they tied knots on rainy days. In the 80’s Ansel Chaplin and Charles Davidson created the Conservation Trust and Bill’s mother was on the Board. Both parents also volunteered in Connecticut. William Worthington Almost as soon as Bill moved out here in 2001, Ansel Senior of the Year Chaplin suggested that he join the Planning Board. He was Chair for a little while and is still on the Board. He is newly on the Provincetown Water and Sewer Board which because of the new North Unionfield well site, requires 3 members INSIDE THIS ISSUE from Truro. Truro has leased this well site - Provincetown does not Senior Citizen of the Year own it which is a different set-up from the other Truro well sites. Bill is also on the Truro Water Resources Oversight Committee. Beyond Store Bought: They are working on a comprehensive water management plan Eco-Chic Gift Wrapping concerning nitrate intrusion. Bill is on the Energy Committee, and for a while he was Truro’s Live Your Life Well representative to the Cape Light Compact. -

US Citizens As Enemy Combatants

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 18 Issue 2 Volume 18, Spring 2004, Issue 2 Article 14 U.S. Citizens as Enemy Combatants: Indication of a Roll-Back of Civil Liberties or a Sign of our Jurisprudential Evolution? Joseph Kubler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. U.S. CITIZENS AS ENEMY COMBATANTS; INDICATION OF A ROLL-BACK OF CIVIL LIBERTIES OR A SIGN OF OUR JURISPRUDENTIAL EVOLUTION? JOSEPH KUBLER I. EXTRAORDINARY TIMES Exigent circumstances require our government to cross legal boundaries beyond those that are unacceptable during normal times. 1 Chief Justice Rehnquist has expressed the view that "[w]hen America is at war.., people have to get used to having less freedom."2 A tearful Justice Sandra Day O'Connor reinforced this view, a day after visiting Ground Zero, by saying that "we're likely to experience more restrictions on our personal freedom than has ever been the case in our country."3 However, extraordinary times can not eradicate our civil liberties despite their call for extraordinary measures. "Lawyers have a special duty to work to maintain the rule of law in the face of terrorism, Justice O'Connor said, adding in a quotation from Margaret 1 See Christopher Dunn & Donna Leiberman, Security v. -

ACLU BLC, Orlando June 12, 2011

ACLU BLC, Orlando June 12, 2011 “Taking Liberties: The ACLU and the War on Terror” During the first week of September 2001, the ACLU got a new Executive Director for the first time in over 20 years. Anthony Romero began work in our current building at 125 Broad Street in downtown Manhattan, a building the ACLU had been occupying for only a few years, having moved down from the Roger Baldwin building on West 43rd Street, in midtown Manhattan, in 1997. During the second week of that month, I don’t need to tell you that downtown Manhattan was devastated, New York City changed, the country changed, and the world changed. And so the ACLU staff, including our new ED, faced all sorts of challenges in adapting to living and working in this new, uncomfortable physical and psychological environment: how do you meet the payroll when everything you need is locked into a building you’re not allowed to enter, and how do you answer a swarm of press inquiries when, in those pre-iPhone days, the computers and telephone systems were inaccessible? One of Anthony’s first tasks was to arrange psychological counseling for some staff members who were traumatized by being so close to the World Trade Center on 9/11 and afterwards. And the entire organization faced the equally daunting challenge of evaluating and responding to the government’s responses to 9/11. By the end of October, less than six weeks after the events of 9/11, Congress had enacted the USA PATRIOT Act which, I will remind you, was an acronym, standing for Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools for Intercepting and Obstructing Terrorism. -

Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics with Taylor Branch

Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics with Taylor Branch 2009 Table of Contents History of the Theodore H. White Lecture .........................................................5 Biography of Taylor Branch ..................................................................................7 Biographies of Nat Hentoff and David Nyhan ..................................................9 Welcoming Remarks by Dean David Ellwood ................................................11 Awarding of the David Nyhan Prize for Political Journalism to Nat Hentoff ................................................................................................11 The 2009 Theodore H. White Lecture on Press and Politics “Disjointed History: Modern Politics and the Media” by Taylor Branch ...........................................................................................18 The 2009 Theodore H. White Seminar on Press and Politics .........................35 Alex S. Jones, Director of the Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy (moderator) Dan Balz, Political Correspondent, The Washington Post Taylor Branch, Theodore H. White Lecturer Elaine Kamarck, Lecturer in Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School Alex Keyssar, Matthew W. Stirling Jr. Professor of History and Social Policy, Harvard Kennedy School Renee Loth, Columnist, The Boston Globe Twentieth Annual Theodore H. White Lecture 3 The Theodore H. White Lecture com- memorates the life of the reporter and historian who created the style and set the standard for contemporary -

Armenian Genocide Memorials in North America

Mashriq & Mahjar 4, no. 1 (2017),59-85 ISSN 2169-4435 Laura Robson MEMORIALIZATION AND ASSIMILATION: ARMENIAN GENOCIDE MEMORIALS IN NORTH AMERICA Abstract The Armenian National Institute lists forty-flve Armenian genocide memorials in the United States and five more in Canada. Nearly all were built after 1980, with a significant majority appearing only after 2000. These memorials, which represent a considerable investment of time, energy, and money on the part of diasporic Armenian communities across the continent, followed quite deliberately on the pattern and rhetoric of the public Jewish American memorialization of the Holocaust that began in the 19705. They tend to represent the Armenian diasporic story in toto as one of violent persecution, genocide, and rehabilitation within a white American immigrant sphere, with the purpose of projecting and promoting a fundamentally recognizable story about diaspora integration and accomplishment. This article argues that the decision publicly to represent the Armenian genocide as parallel to the Holocaust served as a mode of assimilation by attaching diaspora histories to an already recognized narrative of European Jewish immigrant survival and assimilation, but also by disassociating Armenians from Middle Eastern diaspora communities facing considerable public backlash after the Iranian hostage crisis of 1980 and again after September 11,2001. INTRODUCTION For decades after the Armenian genocide, memorialization of the event and its victims remained essentially private among the large Armenian diaspora communities in the United States. But in the 1970s and 1980s, Armenian Americans began to undertake campaigns to fund and build public memorial sites honoring the victims and bringing public attention to the genocide. -

American Protestantism and the Kyrias School for Girls, Albania By

Of Women, Faith, and Nation: American Protestantism and the Kyrias School For Girls, Albania by Nevila Pahumi A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor Pamela Ballinger, Co-Chair Professor John V.A. Fine, Co-Chair Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Mary Kelley Professor Rudi Lindner Barbara Reeves-Ellington, University of Oxford © Nevila Pahumi 2016 For my family ii Acknowledgements This project has come to life thanks to the support of people on both sides of the Atlantic. It is now the time and my great pleasure to acknowledge each of them and their efforts here. My long-time advisor John Fine set me on this path. John’s recovery, ten years ago, was instrumental in directing my plans for doctoral study. My parents, like many well-intended first generation immigrants before and after them, wanted me to become a different kind of doctor. Indeed, I made a now-broken promise to my father that I would follow in my mother’s footsteps, and study medicine. But then, I was his daughter, and like him, I followed my own dream. When made, the choice was not easy. But I will always be grateful to John for the years of unmatched guidance and support. In graduate school, I had the great fortune to study with outstanding teacher-scholars. It is my committee members whom I thank first and foremost: Pamela Ballinger, John Fine, Rudi Lindner, Müge Göcek, Mary Kelley, and Barbara Reeves-Ellington. -

The Armenian Weekly APRIL 26, 2008

Cover 4/11/08 8:52 PM Page 1 The Armenian Weekly APRIL 26, 2008 IMAGES PERSPECTIVES RESEARCH WWW.ARMENIANWEEKLY.COM Contributors 4/13/08 5:48 PM Page 3 The Armenian Weekly RESEARCH PERSPECTIVES 6 Nothing but Ambiguous: The Killing of Hrant Dink in 34 Linked Histories: The Armenian Genocide and the Turkish Discourse—By Seyhan Bayrakdar Holocaust—By Eric Weitz 11 A Society Crippled by Forgetting—By Ayse Hur 38 Searching for Alternative Approaches to Reconciliation: A 14 A Glimpse into the Armenian Patriarchate Censuses of Plea for Armenian-Kurdish Dialogue—By Bilgin Ayata 1906/7 and 1913/4—By George Aghjayan 43 Thoughts on Armenian-Turkish Relations 17 A Deportation that Did Not Occur—By Hilmar Kaiser By Dennis Papazian 19 Scandinavia and the Armenian Genocide— 45 Turkish-Armenian Relations: The Civil Society Dimension By Matthias Bjornlund By Asbed Kotchikian 23 Organizing Oblivion in the Aftermath of Mass Violence 47 Thoughts from Xancepek (and Beyond)—By Ayse Gunaysu By Ugur Ungor 49 From Past Genocide to Present Perpetrator Victim Group 28 Armenia and Genocide: The Growing Engagement of Relations: A Philosophical Critique—By Henry C. Theriault Azerbaijan—By Ara Sanjian IMAGES ON THE COVER: Sion Abajian, born 1908, Marash 54 Photography from Julie Dermansky Photo by Ara Oshagan & Levon Parian, www.genocideproject.net 56 Photography from Alex Rivest Editor’s Desk Over the past few tographers who embark on a journey to shed rials worldwide, and by Rivest, of post- years, the Armenian light on the scourge of genocide, the scars of genocide Rwanda. We thank photographers Weekly, with both its denial, and the spirit of memory.