San Vicente Palawan (SEP-SVP)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

© 2017 Palawan Council for Sustainable Development

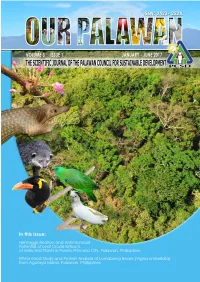

© 2017 Palawan Council for Sustainable Development OUR PALAWAN The Scientific Journal of the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Volume 3 Issue 1, January - June 2017 Published by The Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD) PCSD Building, Sports Complex Road, Brgy. Sta. Monica Heights, Puerto Princesa City P.O. Box 45 PPC 5300 Philippines PCSD Publications © Copyright 2017 ISSN: 2423-222X Online: www.pkp.pcsd.gov.ph www.pcsd.gov.ph Cover Photo The endemic species of Palawan and Philippines (from top to bottom) : Medinilla sp., Palawan Pangolin Manus culionensis spp., Palawan Bearcat Arctictis binturong whitei, Palawan Hill Mynah Gracula religiosa palawanensis, Blue-naped parrot Tanygnathus lucionensis, Philippine Cockatoo Cacatua haematuropydgia. (Photo courtesy: PCSDS) © 2017 Palawan Council for Sustainable Development EDITORS’ NOTE Our Palawan is an Open Access journal. It is made freely available for researchers, students, and readers from private and government sectors that are interested in the sustainable management, protection and conservation of the natural resources of the Province of Palawan. It is accessible online through the websites of Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (pcsd.gov.ph) and Palawan Knowledge Platform for Biodiversity and Sustainable Development (pkp.pcsd.gov.ph). Hard copies are also available in the PCSD Library and are distributed to the partner government agencies and academic institutions. The authors and readers can read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to -

RDO 83-Talisay CT Minglanilla

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE Roxas Boulevard Corner Vito Cruz Street Manila 1004 DEPARTMENT ORDER NO. 44-02 September 16, 2002 SUBJECT : IMPLEMENTATION OF THE REVISED ZONAL VALUES OF REAL PROPERTIES IN THE CITY OF TALISAY UNDER THE JURISDICTION OF REVENUE DISTRICT OFFICE NO. 83 (TALISAY CITY, CEBU), REVENUE REGION NO. 13 (CEBU CITY) FOR INTERNAL REVENUE TAX PURPOSES. TO : All Internal Revenue Officers and Others Concerned. Section 6 (E) of the Republic Act No. 8424, otherwise known as the "Tax Reform Act of 1997"' authorizes the Commissioner of Internal Revenue to divide the Philippines into different zones or areas and determine for internal revenue tax purposes, the fair market value of the real properties located in each zone or area upon consultation with competent appraisers both from private and public sectors. By virtue of said authority, the Commissioner of Internal Revenue has determined the zonal values of real properties (1st revision) located in the city of Talisay under the jurisdiction of Revenue District Office No. 83 (Talisay City, Cebu), Revenue Region No. 13 (Cebu City) after public hearing was conducted on June 7, 2000 for the purpose. This Order is issued to implement the revised zonal values for land to be used in computing any internal revenue tax. In case the gross selling price or the market value shown in the schedule of values of the provincial or city assessor is higher than the zonal value established herein, such values shall be used as basis for computing the internal revenue tax. This Order shall take effect immediately. -

Cruising Guide to the Philippines

Cruising Guide to the Philippines For Yachtsmen By Conant M. Webb Draft of 06/16/09 Webb - Cruising Guide to the Phillippines Page 2 INTRODUCTION The Philippines is the second largest archipelago in the world after Indonesia, with around 7,000 islands. Relatively few yachts cruise here, but there seem to be more every year. In most areas it is still rare to run across another yacht. There are pristine coral reefs, turquoise bays and snug anchorages, as well as more metropolitan delights. The Filipino people are very friendly and sometimes embarrassingly hospitable. Their culture is a unique mixture of indigenous, Spanish, Asian and American. Philippine charts are inexpensive and reasonably good. English is widely (although not universally) spoken. The cost of living is very reasonable. This book is intended to meet the particular needs of the cruising yachtsman with a boat in the 10-20 meter range. It supplements (but is not intended to replace) conventional navigational materials, a discussion of which can be found below on page 16. I have tried to make this book accurate, but responsibility for the safety of your vessel and its crew must remain yours alone. CONVENTIONS IN THIS BOOK Coordinates are given for various features to help you find them on a chart, not for uncritical use with GPS. In most cases the position is approximate, and is only given to the nearest whole minute. Where coordinates are expressed more exactly, in decimal minutes or minutes and seconds, the relevant chart is mentioned or WGS 84 is the datum used. See the References section (page 157) for specific details of the chart edition used. -

Cebu 1(Mun to City)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Map of Cebu Province i Map of Cebu City ii - iii Map of Mactan Island iv Map of Cebu v A. Overview I. Brief History................................................................... 1 - 2 II. Geography...................................................................... 3 III. Topography..................................................................... 3 IV. Climate........................................................................... 3 V. Population....................................................................... 3 VI. Dialect............................................................................. 4 VII. Political Subdivision: Cebu Province........................................................... 4 - 8 Cebu City ................................................................. 8 - 9 Bogo City.................................................................. 9 - 10 Carcar City............................................................... 10 - 11 Danao City................................................................ 11 - 12 Lapu-lapu City........................................................... 13 - 14 Mandaue City............................................................ 14 - 15 City of Naga............................................................. 15 Talisay City............................................................... 16 Toledo City................................................................. 16 - 17 B. Tourist Attractions I. Historical........................................................................ -

Executive Summary

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Community-Based Forest Management Program (CBFMP) revolutionized forest development and rehabilitation efforts of the government when it was institutionalized in 1995 by virtue of Executive Order No. 263. Before the adoption of the CBFM approach, the sole motivating factor of contract reforestation awardees was primarily financial gains. With the implementation of the Forestry Sector Project (FSP) using CBFM as its main strategy to rehabilitate the upland ecosystem, it empowered beneficiary communities economically, socially, technically and politically while transforming them into environmentally responsible managers. The tenurial right to develop subproject sites alongside the various inputs from the Subproject deepened their commitment to collaborate with other stakeholders in the implementation of these subprojects. The Mananga-Kotkot-Lusaran Watershed Subproject is in Cebu Province and covers the cities of Cebu, Talisay and Danao and the municipalities of Minglanilla, Lilo-an, Consolacion, Compostela and Balamban. The rehabilitation of the MKL Watershed is significant considering the declining underground water supply aggravated by salt-water intrusion on the one hand and the continuing and pressing demand for water for Metro Cebu’s industries and residents on the other. The implementation of Comprehensive Site Development ( CSD ) activities for the MKL Subproject involved the participation of 13 People’s Organizations to cover the entire expanse of the three watersheds. With an original target of 5,688 hectares, accomplishment reached only a total of 4,920.75 hectares due to the heavy damage caused by the El Nino phenomenon in 1998 to some 1.0 million seedlings. Realignment of targets focused development and maintenance activities on the improvement of these 4,920.75 hectares. -

Revised Guidelines for Qualified Third Party

Department Circular No. DC2019-11-0015 Prescribing Revised Guidelines for Qualified Third Party Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino PRESENTATION OUTLINE 1 Background 2 Status of Energization 3 Electrification Strategies for Unserved/Underserved Areas 4 Qualified Third Party (QTP) Program 5 Salient Features of the Draft Circular 6 Way Forward Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino Status of Household Electrification Initial Estimate as of June 2019 Philippines 98.33% HHs LUZON 2 Million Households remains unserved out of VISAYAS 96.64% 22.98 Million Households in Households the country 91.72% (Based on DU’s Total Electrification Masterplan) Households MINDANAO 77.23% Households Note: Potential HHs is based on Philippine Statistics Authority - 2015 Population Census Served June Update from Non-Ecs (AEC, CELCOR, CEPALCO, CLPC, DLPC, FBPC (BELS), ILPI, MMPC, OEDC, PECO, SFELAPCO, VECO) Served June 2019 Update from ECs based on NEA Report Department of Energy Empowering the Filipino Electrification Strategies to Address Unserved/Underserved Areas • Program-matching criteria and roll-out scheme to strategically identify appropriate STRATEGY electrification program per specific setup of un- 01 STRATEGY electrified/underserved area/households 02 NIHE ENHANCE STRATEGY SCHEME NIHE SCHEME 07 • Taking into consideration the specific type of SITIO ELECTRIFICATION 100%HH PROGRAM MINI-GRID/ NPC- area: contiguous, island, isolated, etc. vis-as-vis SCHEME STRATEGY SPUG SCHEME Electrification 03 the viability of the areas 2022 STRATEGY BRGY -

Manila, Pli"Ibppines B Flamon Magsaysay Center Telephone: 521-7110 1600 Roxas Boulovard Local 2444-2446 -August 2, 1989

U.S. AGENCY FO0, INTEltNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT 7- 0 . k. Manila, PlI"iBppines B flamon Magsaysay Center Telephone: 521-7110 1600 Roxas Boulovard local 2444-2446 -August 2, 1989 Mr. Carlos T. Soriano Executive Director The Andres Soriano Foundation, Inc; A. Soriano Building 8776 Paseo de Roxas, Makati Metro Manila Dear Mr. Soriano: Subject: Grant No. AID 492-0419-G-SS-9079-00 Pursuant to the authority contained inthe Foreign Assistance Act of 1961, as amended, the Agency for 1.ternational Development (hereinafter referred to as "AID" or "Grantor") hereby grants to the Andres Soriano Foundation, Inc. (hereinafter referred to as "ASF" or Grantee) the sum of V2,940,000 (or $140,000) to implement the "Quiniluban Group of Islands Community Development Project", as ismore fully described in the attachment to this Grant entitled "Program of Work". The Grant iseffective and obligation ismade as of the date of this letter and shall apply to commitments made by the Grantee infurtherance of program objectives during the three-year period beginning with the effective date and ending August 1, 1992. This Grant ismade to the ASF on condition that funds will be administered in accordance with the terms and conditi6ns as set forth inAttachment 1, entitled "Schedule and Project Description", Attachmont 2, entitled "Standard Provisions" which have been agreed to by your organization. Please sign and date the original and seven (7)copies of this Grant to acknowledge your acceptance of the conditions under which these funds have been granted and return the original and six (6)copies to the undersigned. Sincerely, Malcolm Butler Di rector Attachments: 1. -

Over Land and Over Sea: Domestic Trade Frictions in the Philippines – Online Appendix

ONLINE APPENDIX Over Land and Over Sea: Domestic Trade Frictions in the Philippines Eugenia Go 28 February 2020 A.1. DATA 1. Maritime Trade by Origin and Destination The analysis is limited to a set of agricultural commodities corresponding to 101,159 monthly flows. About 5% of these exhibit highly improbable derived unit values suggesting encoding errors. More formally, provincial retail and farm gate prices are used as upper and lower bounds of unit values to check for outliers. In such cases, more weight is given to the volume record as advised by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), and values were adjusted according to the average unit price of the exports from the port of the nearest available month before and after the outlier observation. 2. Interprovince Land Trade Interprovince land trade flows were derived using Marketing Cost Structure Studies prepared by the Bureau of Agricultural Statistics for a number of products in selected years. These studies identify the main supply and destination provinces for certain commodities. The difference between production and consumption of a supply province is assumed to be the amount available for export to demand provinces. The derivation of imports of a demand province is straightforward when an importing province only has one source province. In cases where a demand province sources from multiple suppliers, such as the case of the National Capital Region (NCR), the supplying provinces are weighted according to the sample proportions in the survey. For example, NCR sources onions from Ilocos Norte, Pangasinan, and Nueva Ecija. Following the sample proportion of traders in each supply province, it is assumed that 26% of NCR imports came from Ilocos Norte, 34% from Pangasinan, and 39% from Nueva Ecija. -

The Birds of Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park and World Heritage Site, Palawan Province, Philippines, Including Accounts of Breeding Seabird Population Trends ARNE E

FORKTAIL 32 (2016): 72–85 The birds of Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park and World Heritage Site, Palawan province, Philippines, including accounts of breeding seabird population trends ARNE E. JENSEN & ANGELIQUE SONGCO Data on the seabird population of Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park, Palawan province, Philippines, which lies in the Sulu Sea, date back to 1911. However, regular surveys and monitoring began only in 1997 and have resulted in a wealth of new information. An annotated list of the 106 recorded species is presented and changes in the population of the seven breeding seabird species and the factors that influence such changes are discussed. From an estimated 13,500 breeding seabirds in 1981, the population decreased to less than a third of that number in 2003, with the only Philippine population of Masked Booby Sula dactylatra being extirpated in 1995. Thanks to strict enforcement of a no-visitor policy from 1997, the population increased to around 32,300 birds in 2013. The park is the only known breeding area of the subspecies worcesteri of Black Noddy Anous minutus. It hosts the largest breeding colonies of Brown Booby Sula leucogaster, Greater Crested Tern Thalasseus bergii and Brown Noddy A. stolidus, and the second-largest populations of Red-footed Booby Sula sula and Sooty Tern Onychoprion fuscatus, in the Philippine archipelago. Data on other breeding sites of these species in the archipelago are included. Two new species for the Philippines, 14 new species for Palawan province and four globally threatened species, including the Critically Endangered Christmas Frigatebird Fregata andrewsi, together with first Philippine records of Yellow Wagtail Motacilla flava tschutschensis and M. -

Directory of Participants 11Th CBMS National Conference

Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Academe Dr. Tereso Tullao, Jr. Director-DLSU-AKI Dr. Marideth Bravo De La Salle University-AKI Associate Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 Ms. Nelca Leila Villarin E-Mail: [email protected] Social Action Minister for Adult Formation and Advocacy De La Salle Zobel School Mr. Gladstone Cuarteros Tel No: (02) 771-3579 LJPC National Coordinator E-Mail: [email protected] De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 7212000 local 608 Fax: 7248411 E-Mail: [email protected] Batangas Ms. Reanrose Dragon Mr. Warren Joseph Dollente CIO National Programs Coordinator De La Salle- Lipa De La Salle Philippines Tel No: 756-5555 loc 317 Fax: 757-3083 Tel No: 7212000 loc. 611 Fax: 7260946 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Camarines Sur Brother Jose Mari Jimenez President and Sector Leader Mr. Albino Morino De La Salle Philippines DEPED DISTRICT SUPERVISOR DEPED-Caramoan, Camarines Sur E-Mail: [email protected] Dr. Dina Magnaye Assistant Professor University of the Philippines-SURP Cavite Tel No: (632) 920-6854 Fax: (632) 920-1637 E-Mail: [email protected] Page 1 of 78 Directory of Participants 11th CBMS National Conference "Transforming Communities through More Responsive National and Local Budgets" 2-4 February 2015 Crowne Plaza Manila Galleria Ms. Rosario Pareja Mr. Edward Balinario Faculty De La Salle University-Dasmarinas Tel No: 046-481-1900 Fax: 046-481-1939 E-Mail: [email protected] Mr. -

Y E a R L I N G U P D a T E S

The Black Book Y E A R L I N G U P D A T E S 80th Annual Auction of the Standardbred Horse Sales Company November 5-9, 2018 Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 2018 STANDARDBRED HORSE SALES CO. YEARLING UPDATES (as of Tuesday, October 30, 2018) MONDAY, NOVEMBER 5, 2018 Hip #s 1 - 173 Hip # 1 BACKSTREET ROMEO (Cantab Hall - Backstreet Hanover) 2nd Dam BYE BYE KERRY Producers: UPFRONT BYE BYE (dam of CHELSEES A WINNER 4,1:54.2f-$104,282) Hip # 2 LOU'S SWEETREVENGE (Sweet Lou - Before The Poison) 1st Dam BEFORE THE POISON Poison By The Page $1,368 2nd Dam STIENAM'S GIRL Producers: STIENAM'S PLACE (dam of GOOD DAY MATE $573,541; grandam of ROCKIN THE HOUSE $679,552, ALL STIENAM $384,078, ODDS ON DEMI-QUEUE $278,746, BEACH OGRE $217,909, TALK BACK $160,335, CASH IS KING $101,690, MOUNT ROYAL p,3,1:54.4h, *LOUNATIC p,2,1:55.2f), MS PININFARINA (dam of SIR SAM'S Z TAM $224,229, FAST MOVIN TRAIN $116,726), Buckle Bunni (dam of NICKLE BAG $833,247, SKYWAY BOOMER p,1:51.1f-$136,957), Touch Of Pearls (grandam of STEAL THE DIAMONDS $137,261, MY DAD ROCKS $130,653) Hip # 3 SISTER SLEDGE (Father Patrick - Behindclosedoors) 1st Dam BEHINDCLOSEDOORS Necessity BT2:01.4s 2nd Dam MARGARITA NIGHTS TEQUILA TALKIN 4 wins $41,918 Hip # 4 BONKERS HANOVER (Captaintreacherous - Bettor B Lucky) 1st Dam BETTOR B LUCKY BUTTER BAY HANOVER $10,745 2nd Dam HORNBY LUCKY READ THE PROPOSAL $128,535 Producers: BET ON LUCK (dam of *STARSHIP TROOPER p,2,Q1:55), B So Lucky (dam of CHEESE MELT p,3,1:51.1f) Hip # 5 BRIGHTSIDE HANOVER (Somebeachsomewhere - Bettor's Chance) 2nd Dam PLEASANT THOUGHTS Producers: Ms Dragon Flys (dam of NUCLEAR DRAGON $354,048) Hip # 6 BACK OF THE NECK (Ready Cash - Big Barb) 2nd Dam PINE YANKEE SIGILWIG 2,1:58.2f 2 wins $25,425 Third in John Simpson Mem. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books.