The Case of Heerlen, the Netherlands: How Investing in Culture and Social Networks Improves the Quality of Life in Shrinking Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heerlen, Kerkrade, Venlo En Roermond Laagst Geletterde Gemeentes Van Limburg

Heerlen, Kerkrade, Venlo en Roermond laagst geletterde gemeentes van Limburg • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Laaggeletterdheid is niet alleen een probleem van grote steden in de Randstad. Ook steden in Limburg kampen met hoge percentages laaggeletterden. Sommige steden zelfs met percentages boven de 16%. Cubiss deed onderzoek naar laaggeletterdheid per wijk en kern binnen gemeentes en publiceerde een confronterend resultaat. “Meer dan één op de tien Limburgers heeft moeite met het lezen of schrijven van Nederlands”, zegt Ilse Lodewijks, Projectleider Participatie en zelfredzaamheid bij Cubiss. Cubiss Limburg adviseert en ondersteunt bibliotheken bij hun activiteiten ter voorkoming en vermindering van laaggeletterdheid. De organisatie deed in alle Limburgse gemeentes de ‘Ken uw doelgroep’-analyse, die een beeld geeft van de spreiding van laaggeletterden binnen wijken en kernen. Ilse: “Het landelijk gemiddelde voor laaggeletterdheid is 11,9%. Limburg scoort dus relatief hoog met bijna 13%. Dat was al bekend, maar een analyse om erachter te komen waar de meeste laaggeletterden binnen een gemeente wonen, was nog nooit gedaan.” Percentages laaggeletterden binnen de beroepsbevolking per gemeente Tot 5% Tot 8% Tot 11% Tot 13% Tot 16% 16% of meer -Beek -Echt-Susteren -Horst aan de Maas -Weert -Bergen -Gennep -Venlo -Schinnen -Maasgouw - Beesel -Mook en Middelaar -Roermond -Stein -Roerdalen -Peel en Maas -Venray -Kerkrade -Meerssen Leudal -Maastricht -Heerlen -Nuth -Nederweert -Valkenburg aan de -Sittard-Geleen Geul -Brunssum -Voerendaal -Landgraaf -Onderbanken - Eijsden-Margraten -Gulpen-Wittem -Simpelveld -Vaals Bron : Researchcentrum voor Onderwijs en Arbeidsmarkt (2016). Regionale spreiding van geletterdheid in Nederland. Even schrikken In juni presenteerde Cubiss de bevindingen aan gemeente Sittard-Geleen. Maurice Leenders, beleidsmedewerker bij de gemeente, was in eerste instantie blij. -

Het Beste Van Stein

Het beste van Stein De mooiste wandel- en fietsroute in het Hart van de Maasvallei hartvandemaasvallei.nl #hartvandemaasvallei Genieten in Stein! Wandelen en fietsen in het Hart van de Maasvallei Langs de Nederlands Belgische grens van Maastricht tot Kessenich (BE) vormt de Maas het 40 km lange RivierPark Maasvallei, met in het hart de gemeente Stein. De Maas, een indrukwekkende regen- Stein. Hart van de Maasvallei rivier, boetseerde door de eeuwen heen een veelzijdig en boeiend land- In het hart van het grensoverschrijden- schap. Er ontstond een wirwar van de RivierPark Maasvallei, ligt de groene Avontuur op de Maas oude stroomgeulen, afgesneden gemeente Stein, een waar wandel- en meanders, dijken en uiterwaarden. fietsparadijs en voor velen een nog Bent u avontuurlijk aangelegd? Hoge en lage waterstanden brachten onontdekt stukje Zuid-Limburg. Maak in Stein een kano- of raft- een grote diversiteit mee. Grind, Een plek waar u even weg bent van alle tocht met stroomversnellingen zand en klei vormen de basis voor drukte. Stein is authentiek, veelzijdig onderweg op de grensmaas. een typische flora en fauna. en verrassend en onderscheidt zich De tocht is geschikt voor jong en Stil genieten in het door zijn eigen unieke, stille belevings- oud, met aansluitend een fiets- Historische steden en markante Hart van de Maasvallei wereld binnen het druk bezochte of wandeltocht door een mooi dorpen getuigen van een verleden Zuid-Limburg. rivierenlandschap. Meer informatie vervlochten met de Maas. Naast schitterende wandel- en op hartvandemaasvallei.nl. fietsroutes heeft Stein nog veel Om ervoor te zorgen dat u het hart van meer te bieden. Ontdek bijzondere de Maasvallei optimaal kunt ontdekken musea, geniet van lokale produc- hebben wij de mooiste Maasvallei wandel- en fietsroute voor u geselec- ten en bezoek leuke evenementen. -

Voorstel Inrichting Buffergebied “De Baenjd” Datum; 25 November 2019

Voorstel Inrichting buffergebied “De Baenjd” Datum; 25 november 2019 Projectnaam: Kwistbeek fase 2 waterbuffer Projectnummer: 60-2019-OV-013 Projectgebied: Gemeente Peel en Maas Onderdeel: Helden Versie: Concept/praatstuk Document: Auteur: Ron Janssen Trekkers: Ron Janssen ism gemeente Peel en Maas 1. Inleiding Binnen de gemeente Peel en Maas wordt werk gemaakt om de regenwaterproblematiek op te lossen. Vanuit het veranderende klimaat en de hoeveelheid verharding is het noodzakelijk dat regenwater “gebufferd” kan worden, waarna het gedoseerd zijn weg kan vervolgen. Binnen de gemeente Peel en Maas is samen met Waterschap Limburg het gebied “De Baenjd” benoemd als buffergebied. De gemeente heeft een structuur opgezet met werkgroepen en voor dit onderdeel wil men graag een plan, dat vroegtijdig besproken is met de omgeving. Daarom heeft IKL, Ron Janssen, inzet gepleegd vanuit de kaders Waterschap Limburg en de gemeente Peel en Maas om samen met de streek een voorstel uit te werken. Onderstaand de opzet van het voorstel, dat op 27 november besproken wordt in de Werkgroep. 2. Uitgangspunten en randvoorwaarden Vanuit de opdracht heeft IKL uitgangspunten meegekregen die duidelijk aangeven dat de buffer voor waterretentie functioneel moet zijn en te allen tijde zijn functie kan volbrengen. Vandaar heeft Antea berekend wat de inhoud van de retentiebuffer dient te zijn. Gemeente heeft de beoogde locatie aangegeven. Vanuit deze uitgangspunten heeft de gemeente en werkgroep aangeven wat de aanvullende randvoorwaarden zijn: • Inrichting gebied dient een bijdrage te leveren aan de landschappelijke structuur/cultuurhistorische opbouw van het gebied • Ecologisch mogen bestaande waarden niet in het gedrang komen door wijziging watertoestand/instroom gebiedsvreemd water • De inrichting moet beheersbaar zijn, zodat de functionaliteit ten alle tijden gewaarborgd is. -

Via Belgica Lange Afstands- Wandeling Zuid-Limburg

fietsen wandelen ontdekken proeven Via Belgica lange afstands- wandeling Download de app met routes en augmented reality Zuid-Limburg op www.viabelgica.nl Na tweeduizend jaar kun je de Via Belgica en haar Romeinse hoogtepunten weer bewandelen. De Romeinen stellen ons nog voor een raadsel wat betreft de exacte route, maar ze hebben flink wat sporen achtergelaten. Tijdens deze langeafstands route beleef je heel Romeins Zuid-Limburg, zoals de Romeinse soldaten dat eeuwen geleden al deden. De Via Belgica is een oude Romeinse weg die van het Franse Boulogne sur-Mer naar het Duitse Keulen liep. Op die route doorkruist de Via Belgica Zuid-Limburg. Ze komt bij Maastricht ons land binnen en verlaat Nederland weer bij Rimburg. De aanwezigheid van deze grote Romeinse weg heeft veel in- vloed gehad op het omringende gebied. Tijdens deze wandelroute beleef je Romeins Zuid-Limburg en zie je deze regio met heel andere ogen. Loop een route Route Maastricht Route Valkenburg Route Eygelshoven tot Meerssen tot Heerlen tot Rimburg startpunt: Station startpunt: Station startpunt: Station Maastricht Valkenburg Eygelshoven Stationsplein 29, Stationsstraat 10, Dentgenbachweg 15 6221 BT Maastricht 6301 EZ Valkenburg 6469 XV Kerkrade afstand: 10,5 km afstand: 21,7 km afstand: 13,2 km duur: 2.5 u. duur: 5.30 u. duur: 3.30 u. → zie pagina 2 → zie pagina 6 → zie pagina 10 Route Meerssen Route Heerlen tot Valkenburg tot Eygelshoven startpunt: Station startpunt: Station Meerssen Heerlen Stationstraat 1, Stationsplein 1, 6231 CK Meerssen 6411 NE Heerlen afstand: 12,4 km afstand: 11,7 km duur: 3.15 u. duur: 3.00 u. -

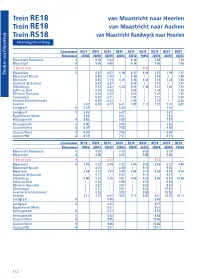

S R 18 R Re18

Trein RE18 van Maastricht naar Heerlen Trein RE18 van Maastricht naar Aachen Maandag Trein RS18 van Maastricht Randwyck naar Heerlen Maandag t/m vrijdag Lijnnummer RE18 RS18 RS18 RE18 RS18 RE18 RS18 RE18 RS18 t/m Ritnummer 20306 32008 32010 20308 32012 19812 32014 20310 32016 vrijdag Maastricht Randwyck V 5 33 6 03 6 33 7 03 7 33 Maastricht A 5 36 6 06 6 36 7 06 7 36 Trein uit Luik A 6 42 Maastricht V 5 37 6 07 6 19 6 37 6 49 7 07 7 19 7 37 Maastricht Noord 5 40 6 10 | 6 40 | 7 10 | 7 40 Meerssen 5 44 6 14 6 24 6 44 6 54 7 14 7 24 7 44 Houthem-St.Gerlach 5 47 6 17 | 6 47 | 7 17 | 7 47 Valkenburg 5 51 6 21 6 30 6 51 7 00 7 21 7 30 7 51 Schin op Geul 5 54 6 24 | 6 54 | 7 24 | 7 54 Klimmen-Ransdaal 5 57 6 27 | 6 57 | 7 27 | 7 57 Voerendaal 6 01 6 31 | 7 01 | 7 31 | 8 01 Heerlen Woonboulevard 6 03 6 33 | 7 03 | 7 33 | 8 03 Heerlen 5 43 6 07 6 37 6 41 7 07 7 11 7 37 7 41 8 07 Landgraaf A 5 47 6 45 7 45 Landgraaf V 5 49 6 47 7 47 Eygelshoven Markt 5 53 6 51 7 51 Herzogenrath A 5 59 6 57 7 57 Herzogenrath V 6 00 6 58 7 58 Aachen West A 6 07 7 05 8 05 Aachen West V 6 08 7 06 8 06 Aachen Hbf A 6 13 7 11 8 11 Lijnnummer RE18 RS18 RE18 RS18 RE18 RS18 RE18 RS18 RE18 Ritnummer 19816 32018 20312 32020 19820 32022 20314 32024 19824 Maastricht Randwyck V 8 03 8 33 9 03 9 33 Maastricht A 8 06 8 36 9 06 9 36 Trein uit Luik A 8 13 9 13 Maastricht V 7 49 8 07 8 19 8 37 8 49 9 07 9 19 9 37 9 49 Maastricht Noord | 8 10 | 8 40 | 9 10 | 9 40 | Meerssen 7 54 8 14 8 24 8 44 8 54 9 14 9 24 9 44 9 54 Houthem-St.Gerlach | 8 17 | 8 47 | 9 17 | 9 47 | Valkenburg 8 -

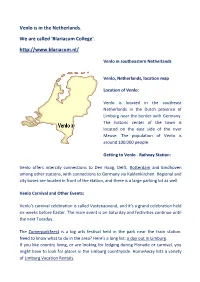

Venlo Is in the Netherlands. We Are Called 'Blariacum College'. Http

Venlo is in the Netherlands. We are called 'Blariacum College'. http://www.blariacum.nl/ Venlo in southeastern Netherlands Venlo, Netherlands, location map Location of Venlo: Venlo is located in the southeast Netherlands in the Dutch province of Limburg near the border with Germany. The historic center of the town is located on the east side of the river Meuse. The population of Venlo is around 100,000 people. Getting to Venlo - Railway Station: Venlo offers intercity connections to Den Haag, Delft, Rotterdam and Eindhoven among other stations, with connections to Germany via Kaldenkirchen. Regional and city buses are located in front of the station, and there is a large parking lot as well. Venlo Carnival and Other Events: Venlo's carnival celebration is called Vastenaovend, and it's a grand celebration held six weeks before Easter. The main event is on Saturday and festivities continue until the next Tuesday. The Zomerparkfeest is a big arts festival held in the park near the train station. Need to know what to do in the area? Here's a long list: a day out in Limburg. If you like country living, or are looking for lodging during Floriade or carnival, you might have to look for places in the Limburg countryside. HomeAway lists a variety of Limburg Vacation Rentals. Closest Airports: Venlo is served by the airports of Düsseldorf (Germany), Maastricht, Eindhoven and Weeze (Germany). Tourist Office: VVV Venlo: The address of the tourist office is Nieuwstraat 40-42, 5911 Venlo. It's open Monday through Friday from 10 am to 5:30 pm and Saturday from 10am to 5pm. -

Summary of the Limburg Region Seminar, November 8-9, 2012

Local Scenarios of Demographic Change: Policies and Strategies for Sustainable Development, Skills and Employment Summary of the Limburg Region Seminar, November 8-9, 2012 Maastricht, December 7, 2012 Summary of the Limburg Region Seminar, November 8-9, 2012 Acknowledgements This summary note has been prepared by Andries de Grip (Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market, Maastricht University) and Inge Monteyne (Zeeland Regional Province). Aldert de Vries, Roxana Chandali (Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations) and Silas Olsson (Health Access) and Karin Jacobs, Hans Mooren (Benelux Union) revised the note and provide useful comments for its final format. The note has been edited by Cristina Martinez-Fernandez (OECD LEED Programme), Tamara Weyman (OECD project consultant) and Melissa Telford (OECD consultant editor). Our gratitude to the workshop participants for their inputs and suggestions during the focus groups. 2 Summary of the Limburg Region Seminar, November 8-9, 2012 List of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Pre-workshop discussion and study visit ........................................................................................................... 4 Limburg Workshop ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Focus group 1. Opportunities within the cross-border labour -

De Vakgroep Plastische Chirurgie Regio Limburg Zoekt Per 1 September 2021 Een

De vakgroep plastische chirurgie regio Limburg zoekt per 1 September 2021 een Plastisch chirurg voor het Hand Fellowship 2021-2022 (0.8 - 1.0 FTE). De vakgroep plastische chirurgie van Zuyderland MC biedt de mogelijkheid om een superspecialisatie te verkrijgen in de hand/pols chirurgie gedurende dit door de NVPC geaccrediteerde fellowship. Het Zuyderland MC is een topklinisch opleidingsziekenhuis gevestigd op twee hoofdlocaties in Zuid- Limburg (Sittard-Geleen en Heerlen). Op hoog niveau biedt dit ziekenhuis excellente en innovatieve patiëntenzorg met kennisoverdracht als een van de speerpunten. Het fellowship van 12 maanden biedt de fellow een verdieping in het deelgebied hand- en polschirurgie. Naast algemene hand- en polschirurgie zijn er expliciete speerpunten zoals de complexe polschirurgie, tetraplegie, plexus brachialis reconstructies en reuma. Tevens is er een intensieve samenwerking met het Maastricht UMC. Het doel van dit fellowship is het opleiden van jonge plastisch chirurgen met de mogelijkheid tot het excelleren tot een vakkundig hand/pols chirurg. Entrustable Professional Activities (EPA’s) vormen de basis van de voortgang en beoordeling. Gezocht wordt naar een collegiale, ambitieuze en gedreven, geregistreerd plastisch chirurg met goede communicatieve vaardigheden en oog voor detail. Salaris zal gebaseerd zijn op een functie in dienstverband volgens AMS schaal. U zal deel gaan uitmaken van de regionale samenwerking van plastisch chirurgen in Limburg en ook in dat verband meedraaien in de dienst. De regiomaatschap Limburg bestaat uit plastisch chirurgen die over locaties Viecurie Venlo, Laurentius Roermond, Zuyderland Heerlen en Geleen-sittard en het MUMC Maastricht werken. Er wordt binnen de regio veel samengewerkt. Voor meer informatie en uw sollicitatie kunt u zich graag vóór 30 juni wenden tot: Dr. -

Programmaplan Preventiecoalitie Sittard-Geleen En CZ

Programmaplan Preventiecoalitie Sittard-Geleen & CZ Versie 13-01-19 Inhoudsopgave Preventiecoalitie Sittard-Geleen & CZ 1. Aanleiding voor samenwerking 2. Uitdagingen in Sittard-Geleen 3. Doelstellingen 4. Aanpak 5. Monitoring en evaluatie 6. Governance 7. Bijlagen 2 De gemeente en CZ hebben ieder hun eigen verantwoordelijk- heden in een gefragmenteerd zorg/ondersteuningslandschap Preventiecoalitie Sittard-Geleen & CZ Zelf / Samen Sociaal domein Medisch domein Samenleving Gemeente Sittard-Geleen CZ CZ Zorgkantoor Wmo Jeugdwet Wet Publieke Gezond- Zvw Wlz heid Participa- Omge- tiewet vingswet Complexiteit van ondersteunings- / zorgvraag 3 Doelgroepen en en hun zorgvragen overstijgen de gefragmenteerde zorg en ondersteuning Preventiecoalitie Sittard-Geleen & CZ Zelf / Samen Sociaal domein Medisch domein Samenleving Gemeente Sittard-Geleen CZ CZ Zorgkantoor Gezonde bevolking Groepen/individuen Individuen met met een verhoogd gezondheidsprobleem gezondheidsrisico Complexiteit van ondersteunings- / zorgvraag 4 Voor verbeteringen in het sociale en medische domein is een gezamenlijke integrale aanpak nodig Preventiecoalitie Sittard-Geleen & CZ Zelf / Samen Sociaal domein Medisch domein Een gezamenlijke integrale aanpak (het in samenhang vormgeven van preventie, welzijn en zorg) is nodig omdat… • Gefragmenteerde ondersteuning en zorg een holistische benadering belemmeren • Veel ondersteunings- en zorgvragen betrekking hebben op zowel het sociale als medische domein • Gemeente en zorgverzekeraar wederzijds afhankelijk zijn • De gemeente heeft -

OGN 2011 Nieuwsbrief 7

Nummer 7 Sittard-Geleen, 30 augustus 2017 Beste collega, Bijgaand de zevende nieuwsbrief inzake de OGN 2011. De contactgroep OGN komt tweemaal per jaar bij elkaar om eventuele knelpunten te bespreken en om overeenstemming te bereiken over te hanteren tarieven en vergoedingen. De contactgroep is samengesteld uit een afvaardiging van Enexis en WML alsmede een afvaardiging van de Limburgse gemeenten. De Limburgse gemeenten worden momenteel vertegenwoordigd door de gemeenten Maastricht, Heerlen, Gulpen-Wittem, Sittard-Geleen en Venray. De contactgroep constateert dat de noord Limburgse gemeenten erg magertjes vertegenwoordigd zijn. Met name deze gemeenten worden hierbij opgeroepen om in de contactgroep aan te schuiven. Met nadruk willen wij erop wijzen veel waarde te hechten aan uw mening en willen we het u mogelijk maken invloed uit te oefenen op de afspraken die met de nutsbedrijven worden gemaakt. In dat licht vernemen wij graag van u of u zich wel of niet, en dan graag gemotiveerd, kunt vinden in de gemaakte afspraken dan wel voorstellen. U kunt uw reactie sturen naar [email protected]. In de eerstvolgende bijeenkomst van de contactgroep zullen de ingekomen reacties door ons worden meegenomen. Vindt u dit te indirect, dan kunt u ook namens uw gemeente in persoon deelnemen aan dit overleg. Als dat het geval is, schroom dan niet en maak dit kenbaar bij de heer Bob Bongers ([email protected]). Naar aanleiding van de zesde nieuwsbrief hebben wij 1 reactie mogen ontvangen en wel van de gemeente Mook en Middelaar. Daarvoor onze dank. Het betrof opmerkingen over hetgeen in de zesde nieuwsbrief vermeld staat over weesleidingen. -

Www . Jfcbs . Nato

HQ JFCBS – 2013 JFC JFCwww.jfcbs.nato.int Welcome to the border triangle Netherlands, Germany and Belgium Congratulations, you are going to stay in one JFC Brunssum and very close to the NATO Air- of the most wonderful and international regi- base in Teveren (Germany). In our cosy town ons of Europe. To make your first steps here as you will find many different restaurants and easy as possible, we would like to assist you as shops in walking distance. we do this for more than 20 years. Hundreds of newly arrived personnel have appreciated In our Bistro Café Fleur you will always meet the personalized attention we give to every someone to share experiences and to learn resident in our owner managed hotel. That’s more about our region. Our friendly staff because we love to host guests from all over speaks English fluently and will be happy to the world! help you with any questions you may have regarding your future life in our neighbour- At City Hotel and the adjacent apartment hood. Among the amenities we offer free building you will find tailor-made accommo- WI-FI throughout the whole building helps dation for you, your family and your pets until you to stay in contact with your friends and you have found your private home. We offer family all over the world. various short-term fully furnished apartments with hotel service. Our house is located in Don´t hesitate to contact us. We are looking the heart of Geilenkirchen, only 15 km from forward to welcoming you to the City Hotel. -

Geleen Kracht

ONTWERP KONINKLIJK BESLUIT Besluit van tot aanwijzing van onroerende zaken ter onteigening in de gemeente Sittard- Geleen krachtens artikel 72a van de onteigeningswet (onteigening voor de aanleg van twee spooronderdoorgangen in verband met het opheffen van de onbewaakte gelijkvloerse spoorwegovergangen Raadskuilderweg en Lintjesweg, met bijkomende werken). Ingevolge artikel 72a, eerste lid, van de onteigeningswet kan onteigening van onroerende zaken plaatsvinden onder meer voor de aanleg en verbetering van wegen, bruggen, spoorwegwerken en kanalen, alsmede daarop rustende zakelijke rechten. Daaronder wordt op grond van artikel 72a, tweede lid sub a, mede begrepen onteigening voor de aanleg en verbetering van de in het eerste lid bedoelde werken en rechtstreeks daaruit voortvloeiende bijkomende voorzieningen ter uitvoering van een bestemmingsplan als bedoeld in artikel 3.1, eerste lid, van de Wet ruimtelijke ordening. Het verzoek tot aanwijzing ter onteigening ProRail B.V. (hierna: verzoeker) heeft Ons bij brief van 24 september 2019, kenmerk STD-GLN-OVW-RW en LW Z002-002579, verzocht, om ten name van ProRail B.V. over te gaan tot het aanwijzen ter onteigening van de onroerende zaken in de gemeente Sittard-Geleen. De onteigening wordt verzocht om de aanleg mogelijk te maken van twee spooronderdoorgangen voor fietsers en voetgangers op de spoortrajecten Maastricht-Sittard tussen km 19.429 en km 19.301 en Sittard-Heerlen tussen km 2.647 en km 2.753 in verband met het opheffen van de onbewaakte gelijkvloerse spoorwegovergangen Raadskuilderweg en Lintjesweg, met bijkomende werken, in de gemeente Sittard-Geleen. Planologische grondslag De onroerende zaken waarop het verzoek betrekking heeft, liggen in de gemeente Sittard-Geleen.