Protein Determination—Method Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Near Infrared Spectroscopy – a Potentially Useful Method for Rapid

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2000) 54, 20±23 ß 2000 Macmillan Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved 0954±3007/00 $15.00 www.nature.com/ejcn Near infrared spectroscopy Ð a potentially useful method for rapid determination of fat and protein content in homogenized diets K Almendingen1, HM Meltzer1,2*, JI Pedersen1,3, BN Nilsen4 and M Ellekjñr4 1Institute for Nutrition Research, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Blindern, Oslo, Norway; 2Department of Environmental Medicine, National Institute of Public Health, Torshov, Oslo, Norway; 3Akershus College, Bekkestua, Norway; and 4Norwegian Food Research Institute, AÊ s, Norway Objective: To investigate the potential of near-infrared re¯ectance (NIR) spectroscopy as a rapid and non- destructive method to determine total fat and protein in mixed, homogenized and freeze-dried human diets. Design: 29 students collected duplicate portions of their diet for four consecutive days. In addition, a detailed food diary was kept. The duplicate portions were analysed for total protein and fat content both by traditional chemical analysis (Kjeldahl and Folch methods) and through the recently developed NIR spectroscopy method. In addition, traditional computerized estimation of nutrient composition was performed. Results: Plotting of the NIR-predicted fat content against the chemically analysed fat content gave a correlation coef®cient of 0.99. Plotting of the NIR-predicted protein content against the Kjeldahl-analysed protein gave a correlation coef®cient of 0.81. Conclusion: NIR-spectroscopy seems to be able to determine fat content in mixed, homogenized diets to a high degree of accuracy. In surveys involving duplicate portion sampling this will save time and money. -

Many Modifications of the Kjeldahl Method Have Been Accepted for the Estimation of Protein in Organic Materials

PROTE.01-1 PROTEIN (Kjeldahl) PRINCIPLE Many modifications of the Kjeldahl method have been accepted for the estimation of protein in organic materials. It comprises sample oxidation and conversion of nitrogen to ammonia, which reacts with excess sulfuric acid, forming ammonium sulfate. The solution is made alkaline and the ammonia is determined by distilling into an excess of standard acid, followed by titrating the excess acid. SCOPE The procedure is applicable to the determination of protein nitrogen in corn, corn starches, corn syrups, feedstuffs and steepwater when suitable amounts of sample, sulfuric acid and catalyst are employed. Without additional modification, it is not applicable to the estimation of total nitrogen in the presence of nitrates and nitrites. SAFETY NOTE Person(s) performing this method should be trained in the handling and disposal of concentrated acids and alkalis, with emphasis on preparation of aqueous solutions, and in coping with potential spills. Accordingly, they should wear appropriate protective equipment and prepare samples and solutions under a fume hood. They should also understand the performance limits and exhaust (scrubber) requirements of the Kjeldahl apparatus available to them. Glassware should be carefully inspected for defects before use. Dispose of spent copper and selenium catalyst according to Good Laboratory Practice and existing regulations. SPECIAL APPARATUS Standard Kjeldahl digestion and distillation equipment in conjunction with 800 mL capacity Kjeldahl flasks and suitable connecting bulbs are recommended. Analytical Methods of the Member Companies of the Corn Refiners Association, Inc. PROTE.01-2 PROTEIN continued REAGENTS 1. Sulfuric Acid, Concentrated: Reagent grade (96% H 2SO 4, sp g 1.84) 2. -

Structural and Functional Studies on Photoactive Proteins and Proteins Involved in Cell Differentiation

Technische Universität München Fakultät für Organishe Chemie und Biochemie Max-Planck-Institut für Biochemie Abteilung Strukturforschung Biologische NMR-Arbeitsgruppe STRUCTURAL AND FUNCTIONAL STUDIES ON PHOTOACTIVE PROTEINS AND PROTEINS INVOLVED IN CELL DIFFERENTIATION Pawel Smialowski Vollständiger Abdruck der von der Fakultät für Chemie der Technischen Universität München zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften genehmigten Dissertation. Vorsitzender: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Dr. A. Bacher Prüfer der Dissertation: 1. apl. Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. R. Huber 2. Univ.-Prof. Dr. W. Hiller Die Dissertation wurde am 10.02.2004 bei der Technischen Universität München eingereicht und durch die Fakultät für Chemie am 17.03.2004 angenommen. PUBLICATIONS Parts of this thesis have been or will be published in due course: Markus H. J. Seifert, Dorota Ksiazek, M. Kamran Azim, Pawel Smialowski, Nedilijko Budisa and Tad A. Holak Slow Exchange in the Chromophore of a Green Fluorescent Protein Variant J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 7932-7942. Markus H. J. Seifert, Julia Georgescu, Dorota Ksiazek, Pawel Smialowski, Till Rehm, Boris Steipe and Tad A. Holak Backbone Dynamics of Green Fluorescent Protein and the effect of Histidine 148 Substitution Biochemistry. 2003 Mar 11; 42(9): 2500-12. Pawel Smialowski, Mahavir Singh, Aleksandra Mikolajka, Narashimsha Nalabothula, Sudipta Majumdar, Tad A. Holak The human HLH proteins MyoD and Id–2 do not interact directly with either pRb or CDK6. FEBS Letters (submitted) 2004. ABBREVIATIONS ABBREVIATIONS -

Dumas Or Kjeldahl for Reference Analysis? Comparison and Considerations for Nitrogen/Protein Analysis of Food and Feed

A White Paper from FOSS Dumas or Kjeldahl for reference analysis? Comparison and considerations for Nitrogen/Protein analysis of food and feed By: Dr. Jürgen Müller Print: June 2017. GB The Dumas method The Dumas combustion method is an absolute method for the determination of the total Nitrogen content in a usually organic matrix. The sample is combusted at high temperature in an oxygen atmosphere. Via subsequent oxidation and reduction tubes, nitrogen is quantitatively converted to N2. Other volatile combustion products are ei- ther trapped or separated. A Thermal Conductivity Detector measures Nitrogen gas. Results are given as % or mg Nitrogen, which may be converted into protein by using conversion factors (table 1). Table 1 – Nitrogen to Protein conversion factors (examples from ISO 16634-1:2008) Commodity Conversion factor Barley 5,88 Coconut meal 5,30 Oats 5,50 Rice 5,95 Rye 5,83 Sun flower (seed, meal) 5,30 Soy bean (seeds, flour or products) 5,71 Triticale 5,78 Wheat (whole meal, flour or bulgur) 5,83 Wheat (bran) 5,26 According to ISO/TS 16634-2:2009 the generally agreed conversion factor for the product analysed, is equal to 5,7 for wheat, rye and their milled products and 6,25 for all other products falling within the scope of this ISO standard. During the 1990’s the Dumas method gained recognition versus the traditional Kjeldahl method that was the dominating method for Crude Protein analysis for more than 100 years. The Dumas method has the advantage of being easy to use and automated. It is also considerably faster than the Kjeldahl method, taking a few minutes per measurement, as compared to an hour or more for Kjeldahl. -

Protein G Agarose

Protein G Agarose Item No Size 223-51-01 10 mL INTRODUCTION Table 1. Relative Affinity of Immobilized Protein G and Protein A for Various Antibody Species and Subclasses of Protein G Agarose consists of recombinant protein G, which is (8) produced in E. coli and after purification, is covalently polyclonal and monoclonal IgG’s . immobilized onto 4% cross-linked agarose beads. Protein G agarose is suitable for the isolation of IgG antibodies using Species/ Subclass Protein G Protein A column or immunoprecipitation methods. DNA sequencing of MONOCLONAL native protein G (from Streptococcal group G) has revealed Human two IgG-binding domains as well as sites for albumin and cell IgG 1 ++++ ++++ surface binding (1 - 6). Protein G has been designed to IgG 2 ++++ ++++ eliminate the albumin and cell surface binding domains to IgG 3 ++++ --- reduce nonspecific binding while maintaining efficient IgG 4 ++++ ++++ binding of the Fc region of IgG’s. With the removal of these binding domains, Protein G can be used to separate albumin Mouse from crude human IgG samples(7). IgG 1 ++++ + IgG 2a ++++ ++++ Covalently coupled Protein G Agarose has been widely used IgG 2b +++ +++ for the isolation of a wide variety of immunoglobulin IgG 3 +++ ++ molecules from several mammalian species. Protein G has greater affinity for many more mammalian IgGs than Protein Rat A (Table 1). IgG 1 + --- IgG 2a ++++ --- FORM/STORAGE IgG 2b ++ --- IgG ++ + Protein G Agarose is supplied in a total volume of 15 mL 2c consisting of 10 mL Protein G agarose suspended in 20% POLYCLONAL ethanol/PBS. Store at 2 - 8°C. -

Thermo Scientific Pierce Protein Purification Technical Handbook

Thermo Scientific Pierce Protein Purification Technical Handbook O O H H2N O N N + Version 2 O Bead Bead H2N Agarose O O NH2 NH2 Table of Contents Introduction for Protein Purification 1-5 Antibody Purification 58-67 Overview 58 Purification Accessories – Protein Extraction, Immobilized Protein L, Protein A, Protein G 59-61 and Protein A/G Binding and Elution Buffers 6-11 IgG Binding and Elution Buffers for 62 Protease and Phosphatase Inhibitors 8 Protein A, G, A/G and L for Protein Purification Melon Gel Purification Products 63 Buffers for Protein Purification 9 Thiophilic Gel Antibody Purification 64 Spin Cups and Columns 10 IgM and IgA Purification 65 Disposable Plastic and Centrifuge Columns 11 Avidin:Biotin Binding 66-69 Fusion Protein Purification 12-21 Biotin-binding Proteins 66 His-Tagged Protein Purification Resin 14-15 Immobilized Avidin Products 67 Cobalt Resin, Spin Columns and 16-17 Immobilized Streptavidin Products 67 Chromatography Cartridges Immobilized NeutrAvidin Products 68 High-quality purification of GST-fusion proteins 18-19 Immobilized Monomeric Avidin and Kit 68 GST- and PolyHis-Tagged Pull-Down Assay Kits 20-21 Immobilized Iminobiotin and Biotin 69 Covalent Coupling of Affinity Ligands FPLC Cartridges 70-77 to Chromatography Supports 22-35 Overview 70 Covalent Immobilization of Ligands 22-25 His-tagged Protein FPLC Purification 71-72 Products for Immobilizing Ligands 26-29 GST-Tagged Protein FPLC Purification 72 through Primary Amines Antibody FPLC Purification 73-75 Products for Immobilizing Ligands 30-32 through Sulfhydryl Groups Phosphoprotein FPLC Purification 75 Products for Immobilizing Ligands 33 Biotinylated Protein FPLC Purification 76 through Carbonyl Groups Protein Desalting 77 Products for Immobilizing Ligands 34-35 through Carboxyl Groups Affinity Supports 78-80 IP/Co-IP 36-45 Immunoprecipitation 36 Traditional Methods vs. -

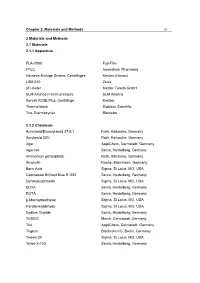

Chapter 2. Materials and Methods 2 Materials and Methods 2.1

Chapter 2. Materials and Methods 20 2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Materials 2.1.1 Apparatus FLA-3000 Fuji-Film FPLC Amersham Pharmacia Heraeus Biofuge Stratos, Centrifuges Kendro (Honau) LSM 510 Zeiss pH-meter Mettler Toledo GmbH SLM Aminco French pressure SLM Aminco Sorvall RC5B Plus, Centrifuge Kendro Thermo-block Bioblock Scientific Trio-Thermocycler Biometra 2.1.2 Chemicals Acrylamid/Bisacrylamid 37:5:1 Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany Acrylamid 30% Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany Agar AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany Agarose Serva, Heidelberg, Germany Ammonium persulphate Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany Ampicilin Roche, Mannheim, Germany Boric Acid Sigma, St Loius, MO, USA Coomassie Brilliant Blue R G25 Serva, Heidelberg, Germany Dimetylsulphoxide Sigma, St Loius, MO, USA EDTA Serva, Heidelberg, Germany EGTA Serva, Heidelberg, Germany β-Mercaptoethanol Sigma, St Loius, MO, USA Paraformaldehyde Sigma, St Loius, MO, USA Sodium fluoride Serva, Heidelberg, Germany TEMED Merck, Darmstadt, Germany Tris AppliChem, Darmstadt, Germany Trypsin Biochrom KG, Berlin, Germany Tween-20 Sigma, St Loius, MO, USA Triton X-100 Serva, Heidelberg, Germany Chapter 2. Materials and Methods 21 2.1.3 Standards and kits ECL Western Blotting Reagents Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden Coomassie Protein Assay kit Pierce, Illinois, USA Qiagen Plasmid Mini Kit Qiagen, Hilden The Netherlands Qiagen Plasmid Midi Kit Qiagen, Hilden, The Netherlands QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit Qiagen, Hilden, The Netherlands QIAquick PCR Extraction Kit Qiagen, Hilden, The Netherlands QIAquick Nucleotide Extraction -

A Tool to Detect Cis-Acting Elements Near Promoter Regions in Rice

Planta (2021) 253:40 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-021-03572-w ORIGINAL ARTICLE Rice protein‑binding microarrays: a tool to detect cis‑acting elements near promoter regions in rice Joung Sug Kim1 · SongHwa Chae1 · Kyong Mi Jun2 · Gang‑Seob Lee3 · Jong‑Seong Jeon4 · Kyung Do Kim1 · Yeon‑Ki Kim1 Received: 27 October 2020 / Accepted: 8 January 2021 / Published online: 21 January 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Main conclusion The present study showed that a rice (Oryza sativa)-specifc protein-binding microarray (RPBM) can be applied to analyze DNA-binding motifs with a TF where binding is evaluated in extended natural promoter regions. The analysis may facilitate identifying TFs and their downstream genes and constructing gene networks through cis-elements. Abstract Transcription factors (TFs) regulate gene expression at the transcriptional level by binding a specifc DNA sequence. Thus, predicting the DNA-binding motifs of TFs is one of the most important areas in the functional analysis of TFs in the postgenomic era. Although many methods have been developed to address this challenge, many TFs still have unknown DNA- binding motifs. In this study, we designed RPBM with 40-bp probes and 20-bp of overlap, yielding 49 probes spanning the 1-kb upstream region before the translation start site of each gene in the entire genome. To confrm the efciency of RPBM technology, we selected two previously studied TFs, OsWOX13 and OsSMF1, and an uncharacterized TF, OsWRKY34. We identifed the ATT GAT TG and CCA CGT CA DNA-binding sequences of OsWOX13 and OsSMF1, respectively. In total, 635 and 932 putative feature genes were identifed for OsWOX13 and OsSMF1, respectively. -

Analysis of the Biochemical and Cellular Activities of Substrate Binding by the Molecular Chaperone Hsp110/Sse1

The Texas Medical Center Library DigitalCommons@TMC The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Biomedical Sciences Dissertations and Theses Center UTHealth Graduate School of (Open Access) Biomedical Sciences 5-2017 ANALYSIS OF THE BIOCHEMICAL AND CELLULAR ACTIVITIES OF SUBSTRATE BINDING BY THE MOLECULAR CHAPERONE HSP110/SSE1 Veronica M. Garcia Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/utgsbs_dissertations Part of the Biochemistry Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, Microbiology Commons, Molecular Biology Commons, and the Molecular Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Garcia, Veronica M., "ANALYSIS OF THE BIOCHEMICAL AND CELLULAR ACTIVITIES OF SUBSTRATE BINDING BY THE MOLECULAR CHAPERONE HSP110/SSE1" (2017). The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences Dissertations and Theses (Open Access). 771. https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/utgsbs_dissertations/771 This Dissertation (PhD) is brought to you for free and open access by the The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at DigitalCommons@TMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences Dissertations and Theses (Open Access) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@TMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANALYSIS OF THE BIOCHEMICAL AND CELLULAR ACTIVITIES OF SUBSTRATE BINDING BY THE MOLECULAR CHAPERONE HSP110/SSE1 By Veronica Margarita Garcia, B.S. APPROVED: _______________________________ Supervisory Professor Kevin A. Morano, Ph.D. _______________________________ Catherine Denicourt, Ph.D. _______________________________ Theresa M. Koehler, Ph.D. _______________________________ Michael C. -

Protein Determination by Kjeldahl Method

Protein determination by Kjeldahl method Item Type book_section Authors Lim, Pang Yong Publisher Marine Fisheries Research Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center Download date 27/09/2021 04:31:09 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/40994 PROTEIN DETERMINATION BY KJELDAHL METHOD LIM P.Y. INTRODUCTION In the presence of sulphuric acid and catalyst, the nitrogen atom in the nitrogenous organic compound is converted to ammonium sulphate. The ammonia is then distilled from an alkaline medium and absorbed in boric acid. The ammonia is then determined by titration with a standard mineral acid. Taking protein as an example, it is as follows:- h2so4 Protein N (NH4)2SO4 + CO2 ↑ + H2O Catalyst (NH4)2SO4 + NaOH → Na2SO4 + 2NH4OH NH4OH → NH3 + H2O 3NH3 + H3BO3 → NH4 + BO3 BO3 + 3H+ → H3BO3 I APPARATUS Kjeldahl digestion and assembly (“Tecator” brand) Kjeldahl digestion tube, 250 ml Kjeldahl distillation apparatus (“Tecator” brand) Conical flask 250 ml Automatic burettes 50 ml with 2000 ml reservoir bottle Magnetic stirrer II REAGENTS a) Sulphuric acid (H2SO4), nitrogen free b) Catalyst Mix 9 parts of potassium sulphate (K2SO4) anhydrous, nitrogen free with 1 part of copper sulphate (CuSO4), anhydrous, nitrogen free. c) NaOH solution (40% w/v) Dissolve sodium hydroxide (NaOH), technical grade, mini pearls, in distilled water. d) Boric acid (4% w/v) e) Anti-bumping granules f) Ethanol (95% v/v) g) Standard 0.1N Sulphuric acid Break ampoule for preparation of standard solution, empty content into 1 L volumetric flask and dilute with nitrogen free distilled water until the mark. Cap and invert the volumetric flask until solution well mix. -

Sensitive Single Molecule Protein Quantification and Protein Complex

Proteomics 2011, 11, 4731–4735 DOI 10.1002/pmic.201100361 4731 TECHNICAL BRIEF Sensitive single-molecule protein quantification and protein complex detection in a microarray format Lee A. Tessler and Robi D. Mitra Department of Genetics, Center for Genome Sciences and Systems Biology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, USA Single-molecule protein analysis provides sensitive protein quantitation with a digital read- Received: June 30, 2011 out and is promising for studying biological systems and detecting biomarkers clinically. Accepted: October 3, 2011 However, current single-molecule platforms rely on the quantification of one protein at a time. Conventional antibody microarrays are scalable to detect many proteins simultaneously, but they rely on less sensitive and less quantitative quantification by the ensemble averaging of fluorescent molecules. Here, we demonstrate a single-molecule protein assay in a microarray format enabled by an ultra-low background surface and single-molecule imaging. The digital read-out provides a highly sensitive, low femtomolar limit of detection and four orders of magnitude of dynamic range through the use of hybrid digital-analog quantifica- tion. From crude cell lysate, we measured levels of p53 and MDM2 in parallel, proving the concept of a digital antibody microarray for use in proteomic profiling. We also applied the single-molecule microarray to detect the p53–MDM2 protein complex in cell lysate. Our study is promising for development and application of single-molecule protein methods because it represents a technological bridge between single-plex and highly multiplex studies. Keywords: Antibody microarray / Sandwich immunoassay / Single-molecule detection / Technology / Total internal reflection fluorescence Single-molecule protein detection has the potential to cence (TIRF) imaging has provided a platform for single- benefit systems biology and biomarker studies by providing molecule quantification on planar surfaces. -

Beta-Barrel Scaffold of Fluorescent Proteins: Folding, Stability and Role in Chromophore Formation

Author's personal copy CHAPTER FOUR Beta-Barrel Scaffold of Fluorescent Proteins: Folding, Stability and Role in Chromophore Formation Olesya V. Stepanenko*, Olga V. Stepanenko*, Irina M. Kuznetsova*, Vladislav V. Verkhusha**,1, Konstantin K. Turoverov*,1 *Institute of Cytology of Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia **Department of Anatomy and Structural Biology and Gruss-Lipper Biophotonics Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA 1Corresponding authors: E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 222 2. Chromophore Formation and Transformations in Fluorescent Proteins 224 2.1. Chromophore Structures Found in Fluorescent Proteins 225 2.2. Autocatalytic and Light-Induced Chromophore Formation and Transformations 228 2.3. Interaction of Chromophore with Protein Matrix of β-Barrel 234 3. Structure of Fluorescent Proteins and Their Unique Properties 236 3.1. Aequorea victoria GFP and its Genetically Engineered Variants 236 3.2. Fluorescent Proteins from Other Organisms 240 4. Pioneering Studies of Fluorescent Protein Stability 243 4.1. Fundamental Principles of Globular Protein Folding 244 4.2. Comparative Studies of Green and Red Fluorescent Proteins 248 5. Unfolding–Refolding of Fluorescent Proteins 250 5.1. Intermediate States on Pathway of Fluorescent Protein Unfolding 251 5.2. Hysteresis in Unfolding and Refolding of Fluorescent Proteins 258 5.3. Circular Permutation and Reassembly of Split-GFP 261 5.4. Co-translational Folding of Fluorescent Proteins 263 6. Concluding Remarks 267 Acknowledgments 268 References 268 Abstract This review focuses on the current view of the interaction between the β-barrel scaf- fold of fluorescent proteins and their unique chromophore located in the internal helix.