Beethoven's Pastoral & Montgomery From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focus on Marie Samuelsson Armas Järnefelt

HIGHLIGHTS NORDIC 4/2018 NEWSLETTER FROM GEHRMANS MUSIKFÖRLAG & FENNICA GEHRMAN Focus on Marie Samuelsson Armas Järnefelt – an all-round Romantic NEWS Joonas Kokkonen centenary 2021 Mats Larsson Gothe awarded Th e major Christ Johnson Prize has been awarded to Th e year 2021 will mark the centenary of the Mats Larsson Gothe for his …de Blanche et Marie…– Jesper Lindgren Photo: birth of Joonas Kokkonen. More and more Symphony No. 3. Th e jury’s motivation is as follows: music by him has been fi nding its way back into ”With a personal musical language, an unerring feeling concert programmes in the past few years, and for form, brilliant orchestration and an impressive craft his opera Viimeiset kiusaukset (Th e Last Temp- of composition, Larsson Gothe passes on with a sure tations) is still one of the Finnish operas hand the great symphonic tradition of our time.” Th e most often performed. Fennica Gehrman has symphony is based on motifs from his acclaimed published a new version of the impressive Requi- opera Blanche and Marie and was premiered by em he composed in 1981 in memory of his wife. the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic during their Th e arrangement by Jouko Linjama is for organ, Composer Weekend Festival 2016. mixed choir and soloists. Th e Cello Concerto has also found an established place in the rep- ertoire; it was heard most recently in the Finals Söderqvist at the Nobel Prize of the International Paulo Cello Competition in Concert October 2018. Ann-Sofi Söder- Photo: Maarit Kytöharju Photo: qvist’s Movements Photo: Pelle Piano Pelle Photo: opens this year’s Finland Vuorjoki/Music Saara Photo: Nobel Prize Con- cert in Stockholm on 9 December. -

2013-2014 Master Class-Ilya Kaler (Violin)

Master Class with Ilya Kaler Sunday, October 13, 2013 at 6:00 p.m. Keith C. and Elaine Johnson Wold Performing Arts Center Boca Raton, Florida Program Concerto No. 3 in B Minor Camille Saint-Saens Allegro non troppo (1835-1921) Mozhu Yan, violin Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Concerto No. 3 in B Minor Camille Saint-Saens Andantino quasi allegretto (1835-1921) Julia Jakkel, violin Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano INTERMISSION Scottish Fantasy, Op. 46 Max Bruch Adagio cantabile (1838-1920) Anna Tsukervanik, violin Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano Violin Concerto No. 1 Niccolo Paganini Allegro maestoso – Tempo giusto (1782-1840) Yordan Tenev, violin Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano ILYA KALER Described by London’s Gramophone as a ‘magician, bewitching our ears’, Ilya Kaler is one of the most outstanding personalities of the violin today. Among his many awards include 1st Prizes and Gold Medals at the Tchaikovsky (1986), the Sibelius (1985) and the Paganini (1981) Competitions. Ilya Kaler was born in Moscow, Russia into a family of musicians. Major teachers at the Moscow Central Music School and the Moscow Conservatory included Zinaida Gilels, Leonid Kogan, Victor Tretyakov and Abram Shtern. Mr Kaler has earned rave reviews for solo appearances with distinguished orchestras throughout the world, which included the Leningrad, Moscow and Dresden Philharmonic Orchestras, the Montreal Symphony, the Danish and Berlin Radio Orchestras, Detroit Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Seattle Symphony, New Japan Philharmonic, the Moscow and Zurich Chamber Orchestras, among others. His solo recitals have taken him throughout the former Soviet Union, the United States, East Asia, Europe, Latin America, South Africa and Israel. -

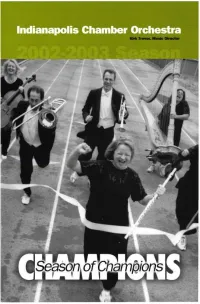

Iseason of Cham/Dions

Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra Kirk Trevor, Music Director ISeason of Cham/Dions <s a sizzling performance San Francisco Examiner October 14, 2002 February 23, 2003 7:30 p.m. 2:30 p.m. Ilya Kaler, violin Gabriela Demeterova, violin November 4, 2002 March 24, 2003 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. Paul Barnes, piano Larry Shapiro, violin Marjorie Lange Hanna, cello Csaba Erdelyi, viola December 15, 2002 April 13, 2003 2:30 p.m. 2:30 p.m. Bach's Christmas Handel's Messiah Oratorio with with Indianapolis Indianapolis Symphonic Choir Symphonic Choir and Eric Stark January 27, 2003 May 12, 2003 7:30 p.m. 7:30 p.m. Christopher Layer, Olga Kern, piano bagpipes simply breath-taking Howard Aibel. New York Concert Review All eight concerts will be performed at Clowes Memorial Hall of Butler University. Tickets are $20 and available at the Clowes Hall box office, Ticket CHAMBER Central and all Ticketmaster ticket ORCHESTRA centers or charge by phone at Kirk Trevor, Music Director 317.239.1000. www.icomusic.org Special Thanks CG>, r:/ /GENERA) L HOTELS CORPORATION For providing hotel accommodations for Maestro Trevor and the ICO guest artists Wiu 103.7> 951k \%ljm 100.7> 2002-2003 Season Media Partner With the support of the ARTSKElNDIANA % d ARTS COUNCIt OF INDIANAPOLIS * ^^[>4foyJ and Cily o( Indianapolis INDIANA ARTS COMMISSJON l<IHWI|>l|l»IMIIW •!••. For their continued support of the arts Shopping for that hard-to-buy-for friend relative spouse co-worker? Try an ICO 3-pak Specially wrapped holiday 3-paks are available! Visit the table in the lobby tonight or call the ICO office at 317.940.9607 The music performed in the lobby at tonight's performance was provided by students from Lawrence Central High School Thank you for sharing your musical talent with us! Complete this survey for a chance to win 2 tickets to the 2003-2004 Clowes Performing Arts Series. -

Shanshan Wei, Violin Opportunity to Share with You the Bachelor of Music Recital Program Beautiful World of Music

Welcome to the 2018-2019 season. The talented students and extraordinary faculty of the Lynn Conservatory of Music take this Shanshan Wei, Violin opportunity to share with you the Bachelor of Music Recital Program beautiful world of music. Your ongoing support ensures our place Sheng-Yuan Kuan and Guzal Isametdinova, piano among the premier conservatories of the world and a staple of our Tuesday, April 30, 2019 at 7:30 p.m. community. Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall - Jon Robertson, dean Boca Raton, Florida There are a number of ways by which you can help us fulfill our mission: Friends of the Conservatory of Music Légende Henryk Wieniawski Lynn University’s Friends of the Conservatory of Music is a volunteer organization that supports high-quality music education (1835-1880) through fundraising and community outreach. Raising more than $2 million since 2003, the Friends support Lynn’s effort to provide free tuition scholarships and room and board to all Conservatory of Music students. The group also raises money for the Dean’s Discretionary Fund, which supports the immediate needs of the Devil's Trill Sonata in G minor Giuseppe Tartini university’s music performance students. This is accomplished through annual gifts and special events, such as outreach Larghetto (1692-1770) concerts and the annual Gingerbread Holiday Concert. Allegro moderato To learn more about joining the Friends and its many benefits, Grave—Allegro assai such as complimentary concert admission, visit Give.lynn.edu/support-music. The Leadership Society of Lynn University The Leadership Society is the premier annual giving society for donors who are committed to ensuring a standard of excellence at Lynn for all students. -

BIOGRAPHY MARIUSZ SMOLIJ Is Considered One of the Most

BIOGRAPHY MARIUSZ SMOLIJ is considered one of the most consummate orchestral conductors of his generation. A frequent recording artist for Naxos International, he has been consistently gaining international critical acclaim, including praise from The New York Times for “compelling performances.” Maestro Smolij has led over 130 orchestras in 28 countries on five continents, appearing in some of the world’s most prestigious concert halls. In North America, he has conducted, among many others, the Houston Symphony, the New Jersey Symphony, the Orchestra of the Chicago Lyric Opera, the St. Louis Philharmonic, the Rochester Philharmonic, the Indianapolis Symphony, the Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra, the New Orleans Philharmonic, the Hartford Symphony and the Symphony Nova Scotia. Internationally, he enjoys a notable reputation, appearing with important symphonic ensembles in Germany, Italy, France, Switzerland, Holland, Israel, China, South Africa, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Bulgaria, Hungary, Serbia, the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic and Poland. Maestro Smolij has appeared on many of the world’s most prestigious concert stages, including Carnegie Hall, New York’s Lincoln Center, Kimmel Center in Philadelphia, the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam, Salle Gaveau in Paris, Tonhalle in Zürich, Bunka Hall in Tokyo, ABC Hall in Johannesburg, the National Art Center in Beijing as well as national concert halls in Poland, Israel, South Korea, Mexico, Serbia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Slovakia, Cyprus, Bolivia and Colombia. He has been invited to conduct at numerous prestigious music festivals including the Rheingau Musik Festival in Germany, the Chorin Festival in Germany, Janáček May in the Czech Republic, La Folle Journée Festival in France, and the Autumn Festival at the National Art Center in Beijing, China. -

2017 Program

THE KLEIN COMPETITION 2017 JUNE 3 & 4 The 32nd Annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition SAN FRANCISCO CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC · JUNE 3 & 4, 2017 1 California Music Center Board of Directors Ruth Short, President Dexter Lowry, Vice President Elaine Klein, Secretary Rebecca McCray, Treasurer Susan Bates Andrew Bradford Michael Gelfand Peter Gelfand Mitchell Sardou Klein Fred Spitz, Executive Director Mitchell Sardou Klein, Artistic Director Board Emeritus Judith Preves Anderson Amnon Goldworth To learn more about CMC, please visit californiamusiccenter.org, email us at info@c aliforniamusiccenter.org or call us at 415/252-1122. On the cover: Violinist Isabella Perron performs at the 2015 Klein Competition dress rehearsal, on her way to Second Prize. On this page: William Langlie-Miletich, bass. First Prize winner, 2016 Photos by Scott Chernis. 2 THE 32ND ANNUAL IRVING M. KLEIN INTERNATIONAL STRING COMPETITION TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 4 5 Welcome The Visionary The Prizes 6 7 8 The Judges Judging/Pianists Commissioned Works 9 10 11 Past Winners Competition Format Artists’ Programs 20 26 29 Artists’ Biographies Donor Appreciation Upcoming Performances SAN FRANCISCO CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC · JUNE 3 & 4, 2017 1 WELCOME We are so pleased to be collaborating again with the San Francisco Conservatory of Music in presenting nine extraordinary string players at the 32nd annual Irving M. Klein International String Competition. The collaboration between the Conservatory and the California Music Center is grounded in our mutual commitment to the development of the finest young musical artists. Over the past three decades, we have introduced hundreds of extraordinary young artists to audiences in San Francisco, the greater Bay Area, and across the United States, and watched with great pride and joy as they have blossomed and taken their places among the most significant musicians in the world. -

Download PDF Here

Selected Coverage March 2008 National HIGHLIGHTS All About Jazz Jerusalem Post New York Magazine (March 30) Baltimore Sun Helter Skelter: Alarm Will Sound turns the Beatles’ ―Revolution 9‖— this is not a joke—into chamber music. Columbia Missourian A French-horn player whimpered like a newborn into one microphone, as a Charlotte Observer violinist murmured through a trumpet mute into another mike so that her Jazz Police voice sounded watery and indistinct. A percussionist smashed and stirred a Naples Daily News bagful of broken glass with a hammer, and a clarinetist blurted the tune to ―There‘s a place in France / Where the naked ladies dance.‖ A sober young New York Magazine man, unaccustomed to performing, wielded one of those old-fashioned San Francisco Chronicle squeezable car horns and in an impassive baritone kept repeating: ―Number Springfield News Leader nine … number nine.‖ Yes, you got it: Welcome to the live, all-acoustic version of Lennon and McCartney‘s foray into musique concrète, Toledo Blade ―Revolution 9,‖ as performed with irresistible panache by the twenty- Wall Street Journal member ensemble Alarm Will Sound. Posted at an exit, the phrase ALARM WILL SOUND is a deterrent: Do not Local open this door. As the group‘s name, it says the opposite: Walk on through, and be rewarded with alarming—or at least fresh, discombobulating, Democrat and Chronicle complex, piquant, and exciting—sounds. The original core of the ensemble Messenger-Post Newspapers came together in 2001 as students at the Eastman School of Music in R News Rochester, and the group has since staked out turf at the center of the fringe 13WHAM-TV of New York‘s musical life. -

BRAHMS SCHUMANN Violin Concertos Ilya

570321 bk BRAHMS US:NAXOS 7/11/08 1:12 PM Page 5 The first movement opens dramatically, the cello syncopation, before the energetic polonaise that Paris, Orchestre National de Lyon, Orchestre National de Lille, National Arts Center Orchestra Ottawa, Toronto orchestral exposition with its two subjects leading to the provides the substance of the last movement. In spite of Symphony, BBC Scottish Symphony, Bournemouth Symphony, Melbourne, West Australia, Tasmania and BRAHMS solo entry with a version of the first subject and the the enthusiastic advocacy of Yehudi Menuhin, who saw Queensland Orchestras, New Zealand Symphony, Hong Kong Philharmonic, and KBS Symphony, and has enjoyed lyrical secondary theme in F major. The movement in the concerto a link between Beethoven and Brahms, successful collaborations with soloists such as Vadim Repin, Hilary Hahn and Pinchas Zukerman. Inkinen is invited follows the plan of a classical concerto, with a formal the work has remained controversial, with some, like regularly to the Finnish National Opera and in 2006 made a very successful début at La Monnaie in Brussels recapitulation that brings the second subject back in D Clara Schumann, sensing in it the decline of conducting The Rite of Spring. His recording with the Bavarian Chamber Philharmonic of works by Mozart has SCHUMANN major. The slow movement starts with a divided cello Schumann’s powers, a reservation she held about other received outstanding reviews and was voted the BBC Music Magazine’s recording of the month. His recordings for section, introducing an element of syncopation before late compositions by her husband. Naxos include works by Sibelius and Rautavaara with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra, as well as a chamber the entry of the soloist with an expressive theme. -

Loh Wei Ken Violin Recital

24 April | WEDNESDAY Loh Wei Ken Violin Recital Kerim Vergazov, piano EDVARD GRIEG Sonata in C Minor for Piano and Violin Op. 45 I. Allegro molto ed appassionato II. Allegretto espressivo alla Romanza III. Allegro animato ALBERTO GINASTERA Pampeana no. 1, Rhapsody for Violin and Piano INTERMISSION (5 minutes) SERGEI PROKOFIEV Violin Sonata in D Major Op. 94bis I. Moderato II. Scherzo - Presto III. Andante IV. Allegro con brio About The Performer Loh Wei Ken began his violin lessons under Mr. Ma Ying Chun at Suzuki Music School when he was only 4 years old, and Mr Foo Say Ming from the age of 9 till 18. He is currently a student at the Yong Siew Toh Conservatory of Music, under the tutelage of Mr Ng Yu-Ying. His teachers included Prof. Joseph Swensen and Mr. Christopher George while on exchange at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. In 2008, at 14 years old, Wei Ken made his first public debut with the SNYO on the Butterfly Lovers Violin Concerto at the Esplanade Concert Hall and toured with the SNYO to Italy to perform the same concerto at the prestigious 10th Florence International Music Festival. During his musical journey, Wei Ken has had the opportunity to study with renowned violinists including Hagai Shaham, Mark Kaplan and Ilya Kaler of the Heifetz International Music Institute and participated in the 1st annual Singapore International Violin Festival. Programme Notes Edvard Grieg, Sonata in C Minor for Piano and Violin Op. 45 While writing the 3 violin sonatas, Grieg’s final violin sonata in C minor had the longest completion period in a few months compared to the first 2 that only took a matter of weeks. -

2016-2017 Master Class-Andrés Cárdenes and Ilya Kaler (Violin)

Welcome to the 2016-2017 season. The talented students and Andrés Cárdenes and Ilya Kaler Violin Masterclass extraordinary faculty of the Lynn Conservatory of Music take this Sheng-Yuan Kuan, piano opportunity to share with you the beautiful world of music. Your Darren Matias, piano ongoing support ensures our place Wednesday, January 25, 2017 at 5:00 p.m. among the premier conservatories of the world and a staple of our Amarnick-Goldstein Concert Hall community. Boca Raton, Fla. - Jon Robertson, dean There are a number of ways by which you can help us fulfill our mission: Violin Sonata No. 9 Op. 47 L. Beethoven Friends of the Conservatory of Music I. Adagio sostenuto Presto (1770 1827) Lynn University’s Friends of the Conservatory of Music is a volunteer organization that supports high-quality music education Yaroslava Poletaeva, violin through fundraising and community outreach. Raising more than $2 million since 2003, the Friends support Lynn’s effort to provide Darren Matias, piano free tuition scholarships and room and board to all Conservatory of Music students. The group also raises money for the Dean’s Discretionary Fund, which supports the immediate needs of the university’s music performance students. This is accomplished through annual gifts and special events, such as outreach concerts and the annual Gingerbread Holiday Concert. Sonata No. 1 in G Minor Johann Sebastian Bach To learn more about joining the Friends and its many benefits, II. Fuga (1685-1750) such as complimentary concert admission, visit give.lynn.edu/friendsoftheconservatory. Junheng Chen, violin The Leadership Society of Lynn University The Leadership Society is the premier annual giving society for donors who are committed to ensuring a standard of excellence at Lynn for all students. -

Juilliard Orchestra Jeffrey Milarsky , Conductor Brenden Zak , Violin

Thursday Evening, November 8, 2018, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard Orchestra Jeffrey Milarsky , Conductor Brenden Zak , Violin AUGUSTA READ THOMAS (b. 1964) Prayer Bells LEONARD BERNSTEIN (1918 –90) Serenade (After Plato’s “Symposium”) Phaedras - Pausanias: Lento - Allegro Aristophanes: Allegretto Eryximachus: Presto Agathon: Adagio Socrates - Alcibiades: Molto tenuto - Allegro molto BRENDEN ZAK , Violin Intermission SERGEI PROKOFIEV (1891 –1953) Suite from Romeo and Juliet Montagues and Capulets The Young Juliet Romeo and Juliet Before Parting Romeo at Juliet’s Tomb Masks Balcony Scene Death of Tybalt Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including one intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program Thomas composed Prayer Bells in 2001 on commission from the Pittsburgh Symphony by James M. Keller Orchestra and its conductor, Mariss Jansons, who presented its premiere on May 4 of Prayer Bells that year. She provided this comment AUGUSTA READ THOMAS about the piece: Born April 24, 1964, in Glen Cove, New York Currently residing in Chicago There is an indisputable journey taking place during the 12-minute composition. Augusta Read Thomas, who began com - In general the score falls into a three-part posing as a child, has become one of the form: a slow-growing introduction of 90 most admired and fêted of her generation seconds (which is a section of music I of American composers. -

Ilya KALER & FRIENDS

Friday, April 6, 2018 • 8:00 P.M. AN EVENING WITH ILYA KALER & FRIENDS Faculty Recital DePaul Concert Hall 800 West Belden Avenue • Chicago Friday, April 6, 2018 • 8:00 P.M. DePaul Concert Hall AN EVENING WITH ILYA KALER & FRIENDS Ilya Kaler, violin Beilin Han, piano with guest artists Jonathan Cohler, clarinet Rasa Vitkauskaite, piano PROGRAM Béla Bartók (1881-1945) Contrasts for clarinet, violin and piano (1938) Verbunkos (Recruiting Dance). Moderato, ben ritmato Pihenö (Relaxation). Lento Sebes (Fast Dance). Allegro vivace Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) Suite from L’Histoire du Soldat (The Soldier’s Tale) (1919) The Soldier’s March The Soldier’s Violin (Scene at the brook) A Little Concert Tango - Waltz - Ragtime The Devil’s Dance Paul Schoenfield (b. 1947) Trio for clarinet, violin and piano (1986) Freylakh March Nigun Kozatzke AN EVENING WITH ILYA KLER & FRIENDS • APRIL 6, 2018 BIOGRAPHIES Ilya Kaler is one of the most outstanding personalities of the violin today, whose career ranges from that of a soloist and recording artist to chamber musician and professor. Mr. Kaler earned rave reviews for his solo appearances with such distinguished orchestras throughout the world as the Leningrad, Moscow and Dresden Philharmonic Orchestras, Montreal Symphony, Danish and Berlin Radio Orchestras, Moscow and Zurich Chamber Orchestras, as well as many of the major American orchestras. Kaler collaborated with a number of outstanding conductors such as Valery Gergiev, Dmitry Kitayenko, Mariss Jansons and Jerzy Semkow. His solo recitals have taken him throughout the five continents. Kaler also performed at many concert venues around the world as a member of The Tempest Trio with cellist Amit Peled and pianist Alon Goldstein.