DANCING in the MOONLIGHT by CHARLES F STERCHI IV a THESIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

One to One: Interpersonal Skills for Managers. INSTITUTION Staff Coll., Bristol (England)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 375 759 HE 027 858 AUTHOR Turner, Colin; Andrews, Philippa TITLE One to One: Interpersonal Skills for Managers. INSTITUTION Staff Coll., Bristol (England). REPORT NO ISBN-0-907659-82-9 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 124p. AVAILABLE FROMStaff College, Coombe Lodge, Blagdon, Bristol, BS18 6RG, England, United Kingdom (12.50 British pounds). PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Administrator Effectiveness; Administrator Guides; Administrator Role; *Administrators; *College Administration; Colleges; Communication Skills; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Interpersonal Competence; Job Skills; Listening Skills; Transactional Analysis IDENTIFIERS Gestalt Psychology; Neurolinguistic Programming ABSTRACT This book explores interpersonal skills for college administrators through analysis of fictional, but typical, scenes and dialogues set at a fictional "Elmdale College". The analysis and discussion use transactional analysis, gestalt psychology, and neuro-linguistic programming theories to help the reader understand the underlying processes that take place in different types of encounters between people. Individual chapters discuss the following skills:(1) establishing good contact and creating rapport; (2) activE, listening; (3) locating ownership of problems;(4) assertive behavior and dealing with requests and refusals;(5) using language well;(6) coping with criticism;(7) exploring personal issues; (8) staying with reality;(9) giving and receiving feedback; (10) interviewing the marginal performer; and (11) examining the role of personal beliefs in a skills-based approach. Appendixes list characters that appear in the scenes, chart the organizational structure of Elmdale College, and offer brief notes on transactional analysis, neuro-linguistic programming, and gestalt psychology. Includes an index. An annotated bibliography contains 17 recommended readings. -

New Yarns and Funny Jokes

f IMfWtMTYLIBRARY^)Of AUKJUNIA h SAMMMO ^^F -J) NEW YARNS AND COMPRISING ORIGINAL AND SELECTED MERIGAN * HUMOR WITH MANY LAUGHABLE ILLUSTRATIONS. Copyright, 1890, by EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE. NEW YORK* EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSB, 29 & 3 1 Beekman Street EXCELSIOR PUBLISHING HOUSE, 29 &. 31 Beekman Street, New York, N. Y. PAYNE'S BUSINESS EDUCATOR AN- ED cyclopedia of the Knowl* edge necessary to the Conduct of Business, AMONG THE CONTENTS ARE: An Epitome of the Laws of the various States of the Union, alphabet- ically arranged for ready reference ; Model Business Letters and Answers ; in Lessons Penmanship ; Interest Tables ; Rules of Order for Deliberative As- semblies and Debating Societies Tables of Weights and Measures, Stand- ard and the Metric System ; lessons in Typewriting; Legal Forms for all Instruments used in Ordinary Business, such as Leases, Assignments, Contracts, etc., etc.; Dictionary of Mercantile Terms; Interest Laws of the United States; Official, Military, Scholastic, Naval, and Professional Titles used in U. S.; How to Measure Land ; in Yalue of Foreign Gold and Silver Coins the United states ; Educational Statistics of the World ; List of Abbreviations ; and Italian and Phrases Latin, French, Spanish, Words -, Rules of Punctuation ; Marks of Accent; Dictionary of Synonyms; Copyright Law of the United States, etc., etc., MAKING IN ALL THE MOST COMPLETE SELF-EDUCATOR PUBLISHED, CONTAINING 600 PAGES, BOUND IN EXTRA CLOTH. PRICE $2.00. N.B.- LIBERAL TERMS TO AGENTS ON THIS WORK. The above Book sent postpaid on receipt of price. Yar]Qs Jokes. ' ' A Natural Mistake. Well, Jim was champion quoit-thrower in them days, He's dead now, poor fellow, but Jim was a boss on throwing quoits. -

Scenes and Impressions Abroad

SCENES IMPRESSIONS ABROAD. E Y THE REV. J. E. ROCKWELL, D.D. NEW YORK: ROBERT CARTER & BROTHERS No. 580 BROADWAY. 1860. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1860, by ROBERT CARTER AND BROTHERS, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York, EDWARD O. JENKINS, Printer # &tcrfotgper, No. 26 Frankfort Strket. ^s Sng*T>y -^-K. Biis/iia - fast^J ^.^T^tc^U^ TO MY WIFE, WHOSE SOCIETY WAS THE CHAEM WHICH MADE THESE SCENES- DELIGHTFUL AND MEMORABLE; TO MY PARENTS, WHOSE IN8TKUCTIONS AND COUNSELS HAVE EVER BEEN WISE, FAITHFUL AND SAFE; TO THE CENTRAL PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH OF BROOKLYN, WHOSE SYMPATHY AND EARNEST CO-OPERATION HAVE MADE MY WORK AS A PASTOR PLEASANT; THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED WITH EVERY FEELING OF RESPECT AND AFFECTION BY THE AUTHOR. SCENES AND IMPRESSIONS ABROAD, PREFACE, The substance of these Scenes and Impres- sions Abroad was presented in the form of a Series of Lectures, before the congregation to which it is my pleasure to minister, without a thought of giving to them any farther pub- licity. Unexpectedly they enlisted such atten- tion and apparent interest, as that it became necessary to adjourn from my Lecture Koom, where they were commenced, to the main Auditory of the Church, which place was filled every Wednesday evening for three months. Most of the Lectures were very fully reported in the columns of the Transcript, of this city, with kind and courteous notices of the course. At the request of many who heard them, or who had read the reports of them, and in Vlll PREFACE. -

Urban Sectoral Training for Usaid Staff (Global)

K:\IAC\AGreer\SHARE \6967-SUM Task Orders\06967-009 (Urban Training)\Products\06967-009 Q3-2002.doc FINAL REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE TRAINING URBAN SECTORAL TRAINING FOR USAID STAFF (GLOBAL) Prepared for Prepared by Clare Romanik The Urban Institute Kathy Alison Training Resources Group Urban Sectoral Training for USAID Staff (Global) United States Agency for International Development Contract No. LAG-I-00-99-00036-00, TO No. 06 THE URBAN INSTITUTE 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 (202) 833-7200 October 2003 www.urban.org UI Project 06967-009 TABLE OF ANNEXES COURSE AGENDA Agenda for Development and Cities: Urban 101—December 2002 Offering ...........................................10 Agenda for Development and Cities: Urban 101—March 2003 Offering .................................................12 Agenda for Cities and Economic Growth—September 2003 Offering .....................................................14 CASE STUDY EXERCISES Local Economic Development Case Study No. 1—Villanueva, Honduras...............................................17 Local Economic Development Case Study No. 2—Smolyan Region, Bulgaria ........................................20 Local Economic Development Case Study No. 3—Central Region, Ghana.............................................24 Local Economic Development Case Study No. 4—Dumyat, Egypt.........................................................28 EVALUATION RESULTS Evaluation Results for Development and Cities: Urban 101—December 2002 Offering............................31 Evaluation -

Amatucci Kristi B 201008 Phd

TEACHER UNDONE by KRISTI BRUCE AMATUCCI (Under the Direction of Elizabeth A. St. Pierre) ABSTRACT A post-qualitative dissertation, this self-study follows the five-year career of a new teacher as she balances competing stresses in, around, and outside the classroom. She transacts with students, fellow teachers, administrators, governmental mandates, prescribed curricula, standardized tests, public scrutiny, the criminal justice system, parents and families of her students, her own family and friends, as well as her desires, histories, and memories. Teaching is not what she thought it was; it overwhelms her. In an attempt to escape the rigors of life as high school teacher and to examine teaching in America today, she returns to the university to pursue her doctoral degree in education, only to find that her questions about teaching multiply, becoming more complex and muddled than she ever imagined. She finds no answers, only a cascade of conundrums. The theoretical framework of this study is post-structuralism, and the author relies primarily on the work of Michel Foucault, Helene Cixous, Judith Butler, and Jacques Derrida, among others, to frame her approach. The methodology of this work is a strategy called writing to know, as outlined by Laurel Richardson and Elizabeth St. Pierre. The author writes in an attempt to untangle her multiple teaching selves; yet as she writes, she finds herself becoming more and more enmeshed, confused, confident, eager, and surprised as she follows the words that pour unbridled out of her. The work does not lend itself to neat conclusions or prescriptions for future teacher education programs. -

The Winter's Tale Study Guide Table of Contents Summary

The Winter's Tale Study Guide Table of Contents Summary..............................................................................................................................................................1 Biography.............................................................................................................................................................4 Themes.................................................................................................................................................................6 Characters...........................................................................................................................................................9 Critical Essays...................................................................................................................................................13 Analysis............................................................................................................................................................891 Quotes...............................................................................................................................................................896 i Summary Summary Polixenes, the king of Bohemia, is the guest of Leontes, the king of Sicilia. The two men were friends since boyhood, and there is much celebrating and joyousness during the visit. At last Polixenes decides that he must return to his home country. Leontes urges him to extend his visit, but Polixenes refuses, saying that -

Tom Swift and His Big Tunnel Or the Hidden City of the Andes

Tom Swift and His Big Tunnel or The Hidden City of the Andes by Victor Appleton 1916 2 Contents 1 An Appeal for Aid 5 2 Explanations 9 3 A Face at the Window 13 4 Tom's Experiments 17 5 Mary's Present 23 6 Mr. Nestor's Letter 27 7 Off for Peru 31 8 The Bearded Man 35 9 The Bomb 39 10 Professor Bumper 43 11 In the Andes 47 12 The Tunnel 53 13 Tom's Explosive 57 14 Mysterious Disappearances 61 15 Frightened Indians 67 16 On the Watch 71 17 The Condor 75 18 The Indian Strike 81 19 A Woman Tells 85 3 4 CONTENTS 20 Despair 89 21 A New Explosive 95 22 The Fight 99 23 A Great Blast 103 24 The Hidden City 107 25 Success 111 Chapter 1 An Appeal for Aid Tom Swift, seated in his laboratory engaged in trying to solve a puzzling question that had arisen over one of his inventions, was startled by a loud knock on the door. So emphatic, in fact, was the summons that the door trembled, and Tom started to his feet in some alarm. \Hello there!" he cried. \Don't break the door, Koku!" and then he laughed. \No one but my giant would knock like that," he said to himself. \He never does seem able to do things gently. But I wonder why he is knocking. I told him to get the engine out of the airship, and Eradicate said he'd be around to answer the telephone and bell. -

STATED SESSION MEETING AGENDA Grace Presbyterian Church Library; 7:00Pm; Tuesday, November 17, 2015

STATED SESSION MEETING AGENDA Grace Presbyterian Church Library; 7:00pm; Tuesday, November 17, 2015 CALL TO ORDER AND OPENING PRAYER – The Rev. Trey Little CLERK’S REPORT & ADMINISTRATIVE MATTERS – David Finck, Clerk of Session • Consent Agenda MODERATOR’S REPORT – The Rev. Trey Little • Examination of Class of 2018 Church Officers • Election of Ruling Elder Commissioners for ECO National Meeting (January 26 – 28, 2016) • Facilities Improvement Team Update • ECO Discipleship Pilot Phase Update • Resolution to Dissolve Pastor Nominating Committee • Calling of a Congregational Meeting on Sunday, January 10, for the Purposes of: o Electing Class of 2018 Deacons and Trustees o Electing Church Officer Nominating Committee o Electing Grace Endowment Fund Trustees COMMITTEE REPORTS: ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE GRACE SCHOOL • See written report attached • No written report provided • Pastors’ Compensation MARRIED LIFE ADULT & JOY • No written report provided • See written report attached MISSIONS CONGREGATIONAL CARE • See written report attached • See written report attached WORSHIP EVANGELISM • See written report attached • See written report attached YOUNG ADULT & COLLEGE FAMILY • See written report attached • See written report attached CLOSING PRAYER NEXT SESSION MEETING: Tuesday, January 19 STATED SESSION MEETING AGENDA – November 17, 2015 Grace Presbyterian Church Session Business Meeting CONSENT AGENDA Tuesday, November 17, 2015 § Approve Minutes of the October 20, 2015 stated Session meeting. § Approve Minutes of the November 1, 2015 called -

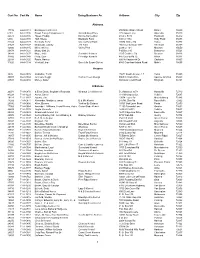

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt. -

(Goff) Genealogy

Family History 1470 -1933 BLOOD.... CABOT HICKS... GOULD AND ALLIED BRANCHES GRACE CABOT BLOOD TOLER THT•J lNDEPENDEXT PRr~:fiS TOLEl:t & TOLii~H. PtrHLrSHERS Genealogical Record OF 'l'HE DESCENDANTS OF RICHARD BLOOD-BAPTIST HICKS AND ALLIED FAMILlZS -1470-1933- INCI.. UDES THE FAMILIES OF Alynt Batt, Benjamin, Billington, Bow:-en_, Cabot,. ea.~e.y.., Chase; Clark, .•!. •.Cl~a~es,.. _.Q>9&Ai,..; :."'--~P'W,.. Darling.. DaV;ts; Dwi.ght,. Eggleston, Eyart, -flint,, Follansbee, Gifford, Gotfe, Gouldt Gru.chy, Han more, HaTWood, Hodgeman-,. i 'l{olden, Hor.ton. J.ahns9n, K!insley, · Liv.ermal:'e, .JA)ngley, Le :a.,:or-ru,, Mansfield. Marrel-1, Marston,. .Martin, Moulton,. Mowry; Nutting, Page; -Pa:rtridge, Pow.ers" ·Rodaera, Bosst· Sabin, Salisbury, Shepard, Tha~~ er, -Toler, Walton, Webster, Whitcomb and Wright. OOM'PILSD AND EDITED BY GRACE CABOT TOLER FOREWORD HE FAAIILY history contained within the pages of this book has been• ··tiff the making -i:11 · my·= mitid since, ~s a small ch.il~. I follo\ved;;~y fa_~_llet· a:ound liste~- T 1ng to everything he had to say pertaining to his. early experiences and to his ancestry, My mother had less to say about her anc.estry and early lite but here and there I gleaned a little from chance remarks. My pa· enta \\·ere in their middle age when I was bo1·n and by the tin1e I bal reach... e~ my teens, my f'ather, especially, was d'\\·eliing ofttm in tht! past. As I gre\\· older; I beg.&n Jotting down the items of fan1- ily interest ·artd after I ma:,rr.i.~tl~!f,~~)" . -

164962 Discerner Jan-Mar 06 R2

no “Hereby k w of truth and the we the spirit spirit of error” The 1 John 4 The :6 DiscernerDiscerner The Voice of the Religion Analysis Service Volume 26, Number 1 January • February • March 2006 A NON-DENOMINATIONAL QUARTERLY EXPOSING UNBIBLICAL TEACHING & MOVEMENTS Office Notes . .2 Dear Reader . .3 By Rev. Laurence J. Sutherland Dispensationalism—Part VI . .4 By Ronald E. McRoberts, PhD The Christian and the Masonic Lodge . .15 By Steve Lagoon Book Reviews . .28 The Discerner 1313 5th St. SE, Suite 126E, Minneapolis, MN 55414-4504 Volume 26, Number 1 612-331-3342 / 1-800-562-9153 January • February • March 2006 FAX 612-331-9222 Editorial Committee Published Quarterly Rev. Laurence J. Sutherland Price $10.00 for 4 issues Dr. William A. BeVier Foreign subscriptions extra Religion Analysis Service Religion Analysis Service Board Members Board Of Reference Dr. Ronald E. McRoberts: President Dr. William A. BeVier Rev. Ervin Ingebretson: Vice President Rev. Ron Carlson Ronald B. Anderson: Treasurer Dr. Norman Geisler Rev. Laurence J. Sutherland: Secretary, Dr. Roy Knuteson Editor of “The Discerner” Dr. David Larsen Rev. Steve Lagoon Rev. David Beebe OFFICE NOTES 1. Our thanks to those who have given extra contributions beyond the subscription price in the last few months. December’s giving was especially encouraging. 2. If you wish to speak to a “live” voice, please call Shawn Ruth, our office manager, Wednesdays - Fridays, 9AM to 2PM. 3. We welcome your feedback on articles in The Discerner. Please feel free to make comments, also suggestions for future issues. 4. RAS would like to extend our deepest gratitude to Mr. -

Tahawus, Newcomb, and Long Lake

Tahawus, Newcomb, and Long Lake. George Shaw, Robert Shaw and John Todd Rexford, NY 1955 LONG LAKE NOTICE A few of these books were made up to assist in the sale of the original. Shaw manuscript, and as elsewhere mentioned, all rights to the text in the first section have now been acquired by the Adirondack Museum, Blue Mountain Lake, New Yorko (1955) The narrative of Tahawus, the Indian, and the Adirondack Iron Works, including the early history of Newcomb and Long Lake was mostly written by George Shaw and later kept up-to-date by his son, Roberto The narratives on the Iron Works may be somewhat imaginery, just how much will probably never be knowne The information on the early settlers in Newcomb and Long Lake are fairly accurate and check with other available sources. In all, it gives a very good picture of the hard ships encountered by these worthy pioneerso They have in the £iles at the Headquarters House of the NeYoS. Historical Association, Cooperstown, NoYo some of the original corres pondence between McIntyre, Henderson and MacMartino According to an article in their January, 1948 publication the three men were, in 1826, shown the vast iron ore deposit in the Tahawus area by an Indian named Lewis Elijah. The Revo John Todd's story on Long Lake, published in 1845, although not quite as direct as Shaw's, contributes some additional informatione A second manuscript, which was recently found, and written by Robert Shaw, describes Robert's personal experiences. It has been included as a second section in a few copies of this particular book for a very limited personal distribution.