Dilemmas in and Pathways to Transboundary Water Cooperation Between China and India on the Yaluzangbu-Brahmaputra River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EURO SKO NORGE AS - Leverandørliste Denne Listen Omfatter Leverandører Som Euro Sko Norge AS Bruker Til Produksjon Av Egne Merkevarer

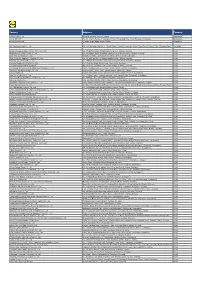

EURO SKO NORGE AS - Leverandørliste Denne listen omfatter leverandører som Euro Sko Norge AS bruker til produksjon av egne merkevarer. Siden leverandørkjeden endres fra tid til annen, for å gjenspeile virksomhetens behov, kan avvik forekomme. Leverandørlisten blir oppdatert årlig. Euro Sko Norge AS har bygget sterke, strategiske bånd med våre leverandører, slik at vi kan offentliggjøre navnene deres, samt plassering uten bekymring for konkurranse i vår bransje. Vi håper offentliggjøringen av listen fremmer deling, samarbeid og bærekraftig produksjon på en måte som kan forbedre arbeidsforholdene og ytterligere beskytte rettighetene for arbeiderene på fabrikkene. Publisert: Juni 2020 Land Garveri navn City/province Albania Fital shpk Kamza/Tirane Bangladesh Apex Dhaka Kina Yangzhou OuHao Handicraft Co., Yangzhou/Jiangsu Zhenjiang Infiniti Shoes Co. Ltd. Zhenjiang/Jiangsu Hengshui Guanyi Leather Products Co Ltd Hengshui/Hebei Yangzhou Duofulai Footwear Co., Ltd. Yangzhou/Jiangsu TM SHOES Zhenjiang/Jiangsu Jinjiang DEVO Shoes & Garments Co., Ltd JinJiang/Fujian Jinbu handicraft Co. Ltd Tianchang/Anhui FuDeLai Zhejiang Dongguan Jiale Shoes Co Ltd. Dongguan/Guangdong Changzhou Qifa Shoes Changzhou/Jiangsu Jolly/JinXi Dongguan/Guangdong LETA FuNan/Anhui Yazhouren Wenzhou/Zhejiang Hangzhou Luke Shoe Co., Ltd. Hangzhou/Zhejiang Shuangha Shuang Ha/Zhejiang Shicheng County Changan Sun Shoes and GarmentGanzhou/JiangxXi Co., Ltd. JinJiang Xinnanxing Shoes and plastic manufacturingChendai/Jinjiang Co Jinjiang Peike Shoes Co., Ltd Chendai/Jinjiang JinJiang Zuta JinJiang/Fujian Fujian Jinjiang Qiaobu Shoes Co.Ltd JinJiang/Fujian Funtag JinJiang/Fujian Huidong Taizifa Shoes Factory HuiZhou/Guangdong Xinyan Shoes Factory HuiZhou/Guangdong Hui Zhou Wei Ming Shoes Co.,Ltd Huangbu Town/Guangdong Shangyuanxin Shoes Factory Huangbu/Guangdong Soon Seng Footwear Company Huiyang City/Guangdong Jinshun Company Dongguan/Guangdong Jin Jiang Xinya Sports Goods Co., Ltd Jwuli/Jinjiang Tengda Sport Products Co Ltd Chidian/Jinjiang Taizhoushi Chiye Shoes Branches Co., Ltd. -

Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.181699 Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China Appendix Appendix Table. Surveillance for carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospitals, Zhejiang Province, China, 2015– 2017* Years Hospitals by city Level† Strain identification method‡ excluded§ Hangzhou First 17 People's Liberation Army Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou First People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Hangzhou Children's Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Hospital of Chinese Traditional Hospital 3A Phoenix 100, VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Cancer Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Xixi Hospital of Hangzhou 3A VITEK 2 Compact Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A VITEK 2 Compact The First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of 3A MALDI-TOF MS Medicine Hangzhou Second People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang People's Armed Police Corps Hospital, Hangzhou 3A Phoenix 100 Xinhua Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Cancer -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

Mr Wang Wuzhong (A) List of Past Directorships (For The

MR WANG WUZHONG (A) LIST OF PAST DIRECTORSHIPS (FOR THE LAST 5 YEARS) Changxing Jinlong Mining Co., Ltd. Sanmenxia Green Energy Environmental Protection Energy Co., Ltd. Wuhan Jinhongde Biological Energy Co., Ltd. Shenyang Jieshen Environmental Energy Technology Co., Ltd. Shanxi Rongguang Energy Co., Ltd Shanxi Heguang Energy Co., Ltd. Baotou Green Energy Jincheng Environmental Protection Co., Ltd. Inner Mongolia Pulate Transportation Energy Co., Ltd. (B) LIST OF PRESENT DIRECTORSHIPS Lamoon Holdings Limited Gevin Limited Hangzhou Xiaoshan Jinjiang Green Energy Co., Ltd. Hangzhou Yuhang Jinjiang Environmental Energy Co., Ltd. Green Energy (Hangzhou) Enterprise Management Co., Ltd. Hangzhou Kesheng Energy Technology Co., Ltd. Zhengzhou Xingjin Green Environmental Energy Co., Ltd. Wuhu Lüzhou Environmental Protection Energy Co., Ltd. Wuhan Hankou Green Energy Co., Ltd. Kunming Xinxingze Environmental Resources Industry Co., Ltd. Yunnan Green Energy Co., Ltd. Zibo Environmental Energy Co., Ltd. Zibo Green Environmental Energy Co., Ltd. Tianjin Sunrise Environmental Protection Science and Technology Development Co., Ltd. Shanghai Sunrise Management Co., Ltd. Yinchuan Zhongke Environmental Electrical Co., Ltd. Hohhot Jiasheng New Energy Co., Ltd. Lianyungang Sunrise Environmental Protection Industry Co., Ltd. Jilin Xinxiang Co., Ltd. Songyuan Xinxiang New Energy Co., Ltd. Suihua Green New Energy Co., Ltd. Qitaihe Green New Energy Co., Ltd. Linzhou Jiasheng New Energy Co., Ltd. Yunnan Jinde Green Energy Co., Ltd. Zhongwei Green New Energy Co., Ltd Gaozhou Green New Energy Co., Ltd. Baishan Green New Energy Co., Ltd. Hunchun Green New Energy Co., Ltd. Tangshan Jiasheng New Energy Co., Ltd. Yulin Green New Energy Co., Ltd. Zibo Green New Energy Co., Ltd. Gaomi Lilangmingde Environmental Protection Technology Co., Ltd. -

1 China Jinjiang Environment Holding Company Limited

CHINA JINJIANG ENVIRONMENT HOLDING COMPANY LIMITED 中国锦江环境控股有限公司 (Company Registration Number: 245144) (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands on 8 September 2010) China International Capital Corporation (Singapore) Pte. Limited was the sole issue manager, global coordinator, bookrunner and underwriter (the “Sole Issue Manager, Global Coordinator, Bookrunner and Underwriter”) for the initial public offering of shares in, and listing of, China Jinjiang Environment Holding Company Limited on the Mainboard of the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited. The Sole Issue Manager, Global Coordinator, Bookrunner and Underwriter assumes no responsibility for the contents of this announcement. THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION OF ZHEJIANG ZHUJI BAFANG THERMAL POWER CO., LTD. (浙江诸暨八方热电有限责任公司) AND WENLING GREEN NEW ENERGY CO., LTD. (温岭绿能新能 源有限公司) 1. INTRODUCTION The Board of Directors (the “Board”) of China Jinjiang Environment Holding Company Limited (the “Company” and together with its subsidiaries, the “Group”) wishes to announce that its wholly-owned subsidiary Gevin Limited (“Gevin”) has on 5 October 2016 entered into the following agreements: (a) a conditional sale and purchase agreement with Hangzhou Jinjiang Group Co., Ltd. ( 杭 州 锦 江 集 团 有 限 公 司 ) (“Jinjiang Group”), a controlling shareholder of the Company, dated 5 October 2016 (the “Zhuji S&P Agreement”) for the acquisition by Gevin, or any of its wholly-owned subsidiaries, of the entire equity interest in Zhejiang Zhuji Bafang Thermal Power Co., Ltd. (浙江诸暨八方热电有限责任公司) (“Zhuji Bafang”) from Jinjiang Group for a total consideration of RMB304,494,000 (equivalent to approximately S$62,482,100) (the “Zhuji Acquisition Consideration”) (the “Proposed Zhuji Acquisition”); and (b) a conditional sale and purchase agreement with Jinjiang Group dated 5 October 2016 (the “Wenling S&P Agreement”) for the acquisition by Gevin, or any of its wholly- owned subsidiaries, of the entire equity interest in Wenling Green New Energy Co., Ltd. -

Levi Strauss & Co. Factory List

Levi Strauss & Co. Factory List Published : November 2019 Total Number of LS&Co. Parent Company Name Employees Country Factory name Alternative Name Address City State Product Type (TOE) Initiatives (Licensee factories are (Workers, Staff, (WWB) blank) Contract Staff) Argentina Accecuer SA Juan Zanella 4656 Caseros Accessories <1000 Capital Argentina Best Sox S.A. Charlone 1446 Federal Apparel <1000 Argentina Estex Argentina S.R.L. Superi, 3530 Caba Apparel <1000 Argentina Gitti SRL Italia 4043 Mar del Plata Apparel <1000 Argentina Manufactura Arrecifes S.A. Ruta Nacional 8, Kilometro 178 Arrecifes Apparel <1000 Argentina Procesadora Serviconf SRL Gobernardor Ramon Castro 4765 Vicente Lopez Apparel <1000 Capital Argentina Spring S.R.L. Darwin, 173 Federal Apparel <1000 Asamblea (101) #536, Villa Lynch Argentina TEXINTER S.A. Texinter S.A. B1672AIB, Buenos Aires Buenos Aires <1000 Argentina Underwear M&S, S.R.L Levalle 449 Avellaneda Apparel <1000 Argentina Vira Offis S.A. Virasoro, 3570 Rosario Apparel <1000 Plot # 246-249, Shiddirgonj, Bangladesh Ananta Apparels Ltd. Nazmul Hoque Narayangonj-1431 Narayangonj Apparel 1000-5000 WWB Ananta KASHPARA, NOYABARI, Bangladesh Ananta Denim Technology Ltd. Mr. Zakaria Habib Tanzil KANCHPUR Narayanganj Apparel 1000-5000 WWB Ananta Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd (Ayesha Bangobandhu Road, Tongabari, Clothing Company Ltd,Hamza Trims Ltd, Gazirchat Alia Madrasha, Ashulia, Bangladesh Hamza Clothing Ltd) Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd( Dhaka Dhaka Apparel 1000-5000 Jamgora, Post Office : Gazirchat Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd (Ayesha Ayesha Clothing Company Ltd(Unit-1)d Alia Madrasha, P.S : Savar, Bangladesh Washing Ltd.) (Ayesha Washing Ltd) Dhaka Dhaka Apparel 1000-5000 Khejur Bagan, Bara Ashulia, Bangladesh Cosmopolitan Industries PVT Ltd CIPL Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000-5000 WWB Epic Designers Ltd 1612, South Salna, Salna Bazar, Bangladesh Cutting Edge Industries Ltd. -

Laboratory Testing for COVID-19

Laboratory Testing for COVID-19 Biotech Centre for Viral Disease Emergency National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention Wenling Wang, PhD [email protected] October 19, 2020 Table of contents 2. Overview Testing 1. techniques PART ONE PART 01 Overview The identification of SARS-CoV-2 Jan 2, 2020 Jan 7, 2020 Samples arrived, RNA isolation and viral Visualization of SARS-CoV-2 with culture transmission electron microscopy 04 02 04 Jan 3, 2020 Jan 12, 2020 01 Whole genome sequencing 03 Sequences submitted to GISAID 03 Timeline of the key events of the COVID-19 outbreak Hu B., et al. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2020 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Situation dashboard Globally, as of 18 October 2020, there have been 39,596,858 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 1,107,374 deaths, reported to WHO. Symptoms of diseases caused by human coronavirus Headache Fever Overall soreness and ache Flu symptoms Chills Dry cough Vomiting PART TWO PART 02 Testing techniques Laboratory testing techniques for COVID-19 √ √ √ Nucleic acid Serological testing testing Viral isolation 2.1 Specimen collection requirements 2.2 Nucleic acid testing Contents 2.3 Antibody testing 2.4 Biosafety requirements Specimen collection Part I requirements ⚫ Collection target ⚫ Requirements for the sampling personnel ⚫ Specimen categories ⚫ Specimen processing ⚫ Specimen packaging and preservation ⚫ Specimen transportation 1. Specimen collection targets 1 Suspected COVID-19 cases; 2 Others requiring diagnosis or differential diagnosis for COVID-19 2. Sample collection requirements Sampling personnel 1. The COVID-2019 testing specimens shall be collected by qualified technicians who have passed biosafety training and are equipped with the corresponding laboratory skills. -

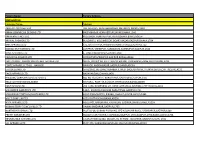

K-Citymarket Factory List Updated August 20Th2018

K-Citymarket Factory list Updated August 20 th 2018 Factory name Address City Province Country Hop Yick (Bangladesh) Ltd Plot #44-46, Depz (West Zone), Ganokbari, Ashuliasavar Dhaka Bangladesh Mondol Fabrics Ltd. Nayapara, Kashimpur Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Parkstar Apparel Ltd Kunia, Kb Bazar,Gazipur Sador, Gazipur Dhaka Bangladesh Shangu Tex Ltd - 2 Dusaid, Ashulia, Savar, Dhaka Dhaka Dhaka Bangladesh Z&Z Intimates Ltd Plot # 1, 2, 3, Road # 02, (Factory Bay Area), Cepz, Chittagong, Chittagong Chittagong Bangladesh Tianyan International (Cambodia)Fashion Co.,Ltd Phum Khva, Sangkat Dongkor, Khan Dongkor, Phnom Penh Phnom Penh Cambodia Municipal Shang Xuan Leather Products Factory No. 6 Li He Street, Li Heng Village, Qingxi Town Dongguan Guangdong China Beijing Joywin Fashion Textile Co. Ltd. No. 3, Ying Quan Street, Yan Qing County Beijing Beijing China Kahung Luggage (Zhangzhou) Co., Ltd Jinmin Road, Beidou Industrial Zone, Jinfeng Economic Development Zone, Zhangzhou Fujian China Bole Shoes Co., Ltd No. 18, Xinya Road, Sanxi Industry Park, Ouhai, Wenzhou Zhejiang China Wenzhou Jiediya Shoes Co.Ltd Dongshou 2nd Floor, No.140, Daluoshan Road, Economic Development Wenzhou Zhejiang China Zone Wenzhou Lihui Shoes Industrial Co., Ltd Yunzhou Industrial Area, Feiyun Town, Ruian Zhejiang China Changzhou Hepu Garments Co.,Ltd No.58 Zhongxing Road,Jintan, Changzhou Jiangsu China Rugao Dingfeng Knitting Textiles Co.,Ltd No 186,Taoli Road,Xiayuan Town,Rugao, Nantong Jiangsu China Taicang Jiebin Garment And Accessory Factory 58 Gangkou Rd, Liuhe -

Factory Name

Factory Name Factory Address BANGLADESH Company Name Address AKH ECO APPARELS LTD 495, BALITHA, SHAH BELISHWER, DHAMRAI, DHAKA-1800 AMAN GRAPHICS & DESIGNS LTD NAZIMNAGAR HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,1340 AMAN KNITTINGS LTD KULASHUR, HEMAYETPUR,SAVAR,DHAKA,BANGLADESH ARRIVAL FASHION LTD BUILDING 1, KOLOMESSOR, BOARD BAZAR,GAZIPUR,DHAKA,1704 BHIS APPARELS LTD 671, DATTA PARA, HOSSAIN MARKET,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1712 BONIAN KNIT FASHION LTD LATIFPUR, SHREEPUR, SARDAGONI,KASHIMPUR,GAZIPUR,1346 BOVS APPARELS LTD BORKAN,1, JAMUR MONIPURMUCHIPARA,DHAKA,1340 HOTAPARA, MIRZAPUR UNION, PS : CASSIOPEA FASHION LTD JOYDEVPUR,MIRZAPUR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH CHITTAGONG FASHION SPECIALISED TEXTILES LTD NO 26, ROAD # 04, CHITTAGONG EXPORT PROCESSING ZONE,CHITTAGONG,4223 CORTZ APPARELS LTD (1) - NAWJOR NAWJOR, KADDA BAZAR,GAZIPUR,BANGLADESH ETTADE JEANS LTD A-127-131,135-138,142-145,B-501-503,1670/2091, BUILDING NUMBER 3, WEST BSCIC SHOLASHAHAR, HOSIERY IND. ATURAR ESTATE, DEPOT,CHITTAGONG,4211 SHASAN,FATULLAH, FAKIR APPARELS LTD NARAYANGANJ,DHAKA,1400 HAESONG CORPORATION LTD. UNIT-2 NO, NO HIZAL HATI, BAROI PARA, KALIAKOIR,GAZIPUR,1705 HELA CLOTHING BANGLADESH SECTOR:1, PLOT: 53,54,66,67,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH KDS FASHION LTD 253 / 254, NASIRABAD I/A, AMIN JUTE MILLS, BAYEZID, CHITTAGONG,4211 MAJUMDER GARMENTS LTD. 113/1, MUDAFA PASCHIM PARA,TONGI,GAZIPUR,1711 MILLENNIUM TEXTILES (SOUTHERN) LTD PLOTBARA #RANGAMATIA, 29-32, SECTOR ZIRABO, # 3, EXPORT ASHULIA,SAVAR,DHAKA,1341 PROCESSING ZONE, CHITTAGONG- MULTI SHAF LIMITED 4223,CHITTAGONG,BANGLADESH NAFA APPARELS LTD HIJOLHATI, -

The Design of the Traffic Plan of Line S1 of Taizhou Railway in Zhejiang Province

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science PAPER • OPEN ACCESS The design of the traffic plan of line S1 of Taizhou railway in Zhejiang Province To cite this article: Zimu Li 2021 IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 791 012079 View the article online for updates and enhancements. This content was downloaded from IP address 170.106.33.42 on 24/09/2021 at 21:19 ACCESE 2021 IOP Publishing IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science 791 (2021) 012079 doi:10.1088/1755-1315/791/1/012079 The design of the traffic plan of line S1 of Taizhou railway in Zhejiang Province Zimu LI1* 1 College of Transport and Communications, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai, 201304, China *Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. At present, China is in the period of rapid urbanization construction, and gradually build a set of efficient, new and fast comprehensive urban transportation system. The urban railway construction with the same city commuter and convenient public transport service can effectively extend the urban development space and accelerate the adjustment process of urban planning and layout. According to the current situation of Taizhou's economic and traffic development, as well as Taizhou's unique geographical advantages, combined with the relevant research at home and abroad, this paper comprehensively discusses the necessity of building Taizhou City railway line S1. By sorting out the relevant preliminary, short-term and long-term passenger flow forecast data, this paper calculates the maximum section passenger flow in each period of the day, analyzes the characteristics of passenger flow in each period, compiles the full-time driving plan compilation data, and makes corresponding adjustments according to the actual situation, and finally designs the full-time driving plan to meet the passenger flow demand in each period. -

Chinese Producers and Exporters of Walk-Behind Lawn Mowers

Chinese Producers and Exporters of Walk-Behind Lawn Mowers 1. Changzhou Globe Co., Ltd. 47 Avenida Do Infan D. Henrique 3-4 65 Xinggang Avenue Macau, Macao Zhhonglou Zone T: 853-853-2871-1715 Changzhou, 213023 China W: www.positecgroup.com T: 86-519-8980-0500 E: [email protected] 7. Changzhou King-Town International W: www.greenworkstools.com.hk No. 50 Juqian Street, Tianning District, 2. Pacific Link International Freight Changzhou, Jiangsu 213000, China (Shanghai) T: 86-519-8816-8225 Room N. 704, E: 86-519-8816-8225 Yaojiang International Mansion No. 308, 8. Zhejiang YAT Electrical Appliance Wu Song Road, Shanghai, China Co. T: 86-21-6031-7066 No. 150 Wenlong Road, F: 86-21-6031-7060 Yuxin Town, E: [email protected] South Lake Zone, Jiaxing 314009, Zhejiang, China 3. Century Distribution Systems T: 86-573-8383-5888 8/F, North Bund Business Center F: 86-573-8383-5577 1050 Dongdaming Road, E: [email protected] Hongkou District W: http://www.yattool.com/ Shanghai 20082, China T: 86-21-5118-3888 9. Scanwell Container Line Ltd. F: 86-21-3105-6140 Room 1002-1003, Block K, Lane 168, W: https://www.cds-net.com/global- The North ChangFeng, Daduhe Road, offices/ Shanghai 200062, China T: 86-25-8473-2035 4. Sumec Hardware and Tools Co., Ltd. W: No.1, Xinghuo Road, http://www.scanwell.com/page?page=G Nanjing Hi-Tech Zone, eneral Ocean Import Nanjing, China T: 86-25-5863-8000 10. Fujian Forestry Materials Co., Ltd. F: 86-25-8563-8018 Qianjiashan Industrial Zone, W: www.sumecpower.com Qingkou Town, Minhou County, Fuzhou, 350119, China 5. -

Brand Supplier/Agent Name COO Factory Name Factory Address

Brand Collective Overseas Supplier List - Version 4, 07 DECEMBER 2017 © Brand Collective Pty Ltd Supplier Brand Supplier/Agent name COO Factory name Factory Address Type CLARKS SHUCRAFT KAILICHENG SHOES LTD CHINA QIANG XING FOOTWEAR LTD NO.3 OF FIRST LANE LONGZHU ROAD,NANQU SHANG TANG INDUSTRIAL ZONE ,ZHONGSHAN CITY ,GUANGDONG PROVINCE AGENT CLARKS MACRO WAY INTERNATIONAL CORP. INDONESIA PT. SHOU FONG LASTINDO PANGMIAO, GANGPING TOWN, HUAJI, ZHAOQING AGENT CLARKS LINK-HO (JINJIANG) IMP. & EXP. CO., LTD. CHINA JIANJIANG JIEFU SHOES CO LTD。 CHIDIAN INDUSTRIAL ZONE, CHIDIAN TOWN JINJIANG AGENT CLARKS LINK-HO (JINJIANG) IMP. & EXP. CO., LTD. CHINA FUJIAN HONGPENG SHOES CO.,LTD YANGGUAN EAST RD. ,HUATINGKOU ,CHENDAI TOWN,JINJIANG CITY AGENT CLARKS JIALIANG INTERNATIONAL CO., LTD CHINA FUYANG FUYUAN SHOES CO.,LTD CHANGLING VILLAGE,YONGCHANG TOWN,FUYANG DISTRIC,HANGZHOU CITY,ZHEJIANG PROVINCE,CHINA AGENT CLARKS KARINDO PUTRA JAYA INDONESIA KARINDO PUTRA JAYA BYPASS KRIAN,DESA BALONG BENDO KM. 17 SIDOARJO,INDONESIA DIRECT CLARKS EVER SMART INTERNATIONAL ENTERPRISE LTD. CHINA WENZHOU JIETU(AOLUN) SHOES FACTORY NO.8 SHUANGBAO WEST ROAD, OUHAI ECONOMIC DEVELOPM P.C. 325014, WENZHOU, CHINA AGENT CLARKS EVER SMART INTERNATIONAL ENTERPRISE LTD. CHINA STRONG MAN 3515 SHOE CO LTD。 NO.197 RENMIN DONG ROAD. LUOHE HENAN,CHINA AGENT CLARKS JINJIANG XINYU SHOES CO., LTD CHINA JINJIANG XINYU SHOES CO., LTD NO.17 YONGJUN ROAD XINBIN TOWN JINJIANG CITY FUJIAN PROVINCE ,CHINA DIRECT CLARKS CORTINA CHINA LTD CHINA CORTINA CHINA LTD NIU DUN INDUSTRIAL ESTATE,HENGLI, WANG NIU DUN, DONGGUAN 523216,GUANGDONG PROVINCE,CHINA AGENT CLARKS HOME FUN SHOES CO., LTD MYANMAR MYANMAR SOE SAN WIN MANUFACTURING CO., LTD.