Spatial and Temporal Variations in Sediment Accumulation in an Algal Turf and Their Impact on Associated Fauna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Studies in Marine Science Artificial Substrates As Sampling

Regional Studies in Marine Science 37 (2020) 101331 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Regional Studies in Marine Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/rsma Artificial substrates as sampling devices for marine epibenthic fauna: A quest for standardization ∗ Diego Carreira-Flores a,b,c, , Regina Neto a, Hugo Ferreira a, Edna Cabecinha c, Guillermo Díaz-Agras b, Pedro T. Gomes a a Centre of Molecular and Environmental Biology, Department of Biology, University of Minho, Portugal b Marine Biology Station of A Graña, University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain c Centre for the Research and Technology of Agro-Environmental and Biological Sciences (CITAB), Department of Biology and Environment, University of Trás-os montes and Alto Douro, Portugal article info a b s t r a c t Article history: In temperate regions, macroalgae are naturally abundant habitat builders for many organisms of Received 6 March 2020 ecological and economic importance. Hence, macroalgae are good targets for monitoring studies based Received in revised form 12 May 2020 on colonization processes as, through them, it is possible to sample the epifauna that uses them as Accepted 28 May 2020 habitat. Nevertheless, macroalgae collection may not be sustainable, can compromise the survival of Available online 30 May 2020 the target macroalgae populations and destroy fragile or threatened communities. Keywords: The search for an adequate procedure that can overcome the problems related to destructive Epifaunal assemblages quantitative sampling of the epifauna associated with macroalgae and the development of a method- Macroalgae ology that can be used for comparative macrofauna monitoring, regardless of the location, were the Artificial Seaweed Monitoring Structures motivations for this study. -

SNH Commissioned Report 765: Seagrass (Zostera) Beds in Orkney

Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 765 Seagrass (Zostera) beds in Orkney COMMISSIONED REPORT Commissioned Report No. 765 Seagrass (Zostera) beds in Orkney For further information on this report please contact: Kate Thompson Scottish Natural Heritage 54-56 Junction Road KIRKWALL Orkney KW15 1AW Telephone: 01856 875302 E-mail: [email protected] This report should be quoted as: Thomson, M. and Jackson, E, with Kakkonen, J. 2014. Seagrass (Zostera) beds in Orkney. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No. 765. This report, or any part of it, should not be reproduced without the permission of Scottish Natural Heritage. This permission will not be withheld unreasonably. The views expressed by the author(s) of this report should not be taken as the views and policies of Scottish Natural Heritage. © Scottish Natural Heritage 2014. COMMISSIONED REPORT Summary Seagrass (Zostera) beds in Orkney Commissioned Report No. 765 Project No: 848 Contractors: Emma Jackson (The Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom) and Malcolm Thomson (Sula Diving) Year of publication: 2014 Keywords Seagrass; Zostera marina; Orkney; predictive model; survey. Background Seagrasses (Zostera spp) are marine flowering plants that develop on sands and muds in sheltered intertidal and shallow subtidal areas. Seagrass beds are important marine habitats but are vulnerable to a range of human induced pressures. Their vulnerability and importance to habitat creation and ecological functioning is recognised in their inclusion on the recommended Priority Marine Features list for Scotland’s seas. Prior to this study, there were few confirmed records of Zostera in Orkney waters. This study combined a predictive modelling approach with boat-based surveys to enhance under- standing of seagrass distribution in Orkney and inform conservation management. -

Laboratory Reference Module Summary Report LR22

Laboratory Reference Module Summary Report Benthic Invertebrate Component - 2017/18 LR22 26 March 2018 Author: Tim Worsfold Reviewer: David Hall, NMBAQCS Project Manager Approved by: Myles O'Reilly, Contract Manager, SEPA Contact: [email protected] MODULE / EXERCISE DETAILS Module: Laboratory Reference (LR) Exercises: LR22 Data/Sample Request Circulated: 10th July 2017 Sample Submission Deadline: 31st August 2017 Number of Subscribing Laboratories: 7 Number of LR Received: 4 Contents Table 1. Summary of mis-identified taxa in the Laboratory Reference module (LR22) (erroneous identifications in brackets). Table 2. Summary of identification policy differences in the Laboratory Reference Module (LR22) (original identifications in brackets). Appendix. LR22 individual summary reports for participating laboratories. Table 1. Summary of mis-identified taxa in the Laboratory Reference Module (LR22) (erroneous identifications in brackets). Taxonomic Major Taxonomic Group LabCode Edits Polychaeta Oligochaeta Crustacea Mollusca Other Spio symphyta (Spio filicornis ) - Leucothoe procera (Leucothoe ?richardii ) - - Scolelepis bonnieri (Scolelepis squamata ) - - - - BI_2402 5 Laonice (Laonice sarsi ) - - - - Dipolydora (Dipolydora flava ) - - - - Goniada emerita (Goniadella bobrezkii ) - Nebalia reboredae (Nebalia bipes ) - - Polydora sp. A (Polydora cornuta ) - Diastylis rathkei (Diastylis cornuta ) - - BI_2403 7 Syllides? (Anoplosyllis edentula ) - Abludomelita obtusata (Tryphosa nana ) - in mixture - - Spirorbinae (Ditrupa arietina ) - - - - -

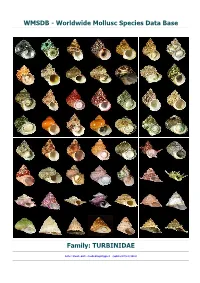

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base

WMSDB - Worldwide Mollusc Species Data Base Family: TURBINIDAE Author: Claudio Galli - [email protected] (updated 07/set/2015) Class: GASTROPODA --- Clade: VETIGASTROPODA-TROCHOIDEA ------ Family: TURBINIDAE Rafinesque, 1815 (Sea) - Alphabetic order - when first name is in bold the species has images Taxa=681, Genus=26, Subgenus=17, Species=203, Subspecies=23, Synonyms=411, Images=168 abyssorum , Bolma henica abyssorum M.M. Schepman, 1908 aculeata , Guildfordia aculeata S. Kosuge, 1979 aculeatus , Turbo aculeatus T. Allan, 1818 - syn of: Epitonium muricatum (A. Risso, 1826) acutangulus, Turbo acutangulus C. Linnaeus, 1758 acutus , Turbo acutus E. Donovan, 1804 - syn of: Turbonilla acuta (E. Donovan, 1804) aegyptius , Turbo aegyptius J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Rubritrochus declivis (P. Forsskål in C. Niebuhr, 1775) aereus , Turbo aereus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) aethiops , Turbo aethiops J.F. Gmelin, 1791 - syn of: Diloma aethiops (J.F. Gmelin, 1791) agonistes , Turbo agonistes W.H. Dall & W.H. Ochsner, 1928 - syn of: Turbo scitulus (W.H. Dall, 1919) albidus , Turbo albidus F. Kanmacher, 1798 - syn of: Graphis albida (F. Kanmacher, 1798) albocinctus , Turbo albocinctus J.H.F. Link, 1807 - syn of: Littorina saxatilis (A.G. Olivi, 1792) albofasciatus , Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albofasciatus , Marmarostoma albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 - syn of: Turbo albofasciatus L. Bozzetti, 1994 albulus , Turbo albulus O. Fabricius, 1780 - syn of: Menestho albula (O. Fabricius, 1780) albus , Turbo albus J. Adams, 1797 - syn of: Rissoa parva (E.M. Da Costa, 1778) albus, Turbo albus T. Pennant, 1777 amabilis , Turbo amabilis H. Ozaki, 1954 - syn of: Bolma guttata (A. Adams, 1863) americanum , Lithopoma americanum (J.F. -

Phylum MOLLUSCA

285 MOLLUSCA: SOLENOGASTRES-POLYPLACOPHORA Phylum MOLLUSCA Class SOLENOGASTRES Family Lepidomeniidae NEMATOMENIA BANYULENSIS (Pruvot, 1891, p. 715, as Dondersia) Occasionally on Lafoea dumosa (R.A.T., S.P., E.J.A.): at 4 positions S.W. of Eddystone, 42-49 fm., on Lafoea dumosa (Crawshay, 1912, p. 368): Eddystone, 29 fm., 1920 (R.W.): 7, 3, 1 and 1 in 4 hauls N.E. of Eddystone, 1948 (V.F.) Breeding: gonads ripe in Aug. (R.A.T.) Family Neomeniidae NEOMENIA CARINATA Tullberg, 1875, p. 1 One specimen Rame-Eddystone Grounds, 29.12.49 (V.F.) Family Proneomeniidae PRONEOMENIA AGLAOPHENIAE Kovalevsky and Marion [Pruvot, 1891, p. 720] Common on Thecocarpus myriophyllum, generally coiled around the base of the stem of the hydroid (S.P., E.J.A.): at 4 positions S.W. of Eddystone, 43-49 fm. (Crawshay, 1912, p. 367): S. of Rame Head, 27 fm., 1920 (R.W.): N. of Eddystone, 29.3.33 (A.J.S.) Class POLYPLACOPHORA (=LORICATA) Family Lepidopleuridae LEPIDOPLEURUS ASELLUS (Gmelin) [Forbes and Hanley, 1849, II, p. 407, as Chiton; Matthews, 1953, p. 246] Abundant, 15-30 fm., especially on muddy gravel (S.P.): at 9 positions S.W. of Eddystone, 40-43 fm. (Crawshay, 1912, p. 368, as Craspedochilus onyx) SALCOMBE. Common in dredge material (Allen and Todd, 1900, p. 210) LEPIDOPLEURUS, CANCELLATUS (Sowerby) [Forbes and Hanley, 1849, II, p. 410, as Chiton; Matthews. 1953, p. 246] Wembury West Reef, three specimens at E.L.W.S.T. by J. Brady, 28.3.56 (G.M.S.) Family Lepidochitonidae TONICELLA RUBRA (L.) [Forbes and Hanley, 1849, II, p. -

Identity of Turbo Bryereus Montagu, Description of a New Rissoidae

BASTERIA, 54: 115-121, 1990 Studies on West Indian marine molluscs 19. On the of Turbo with the of identity Bryereus Montagu, 1803, description a new species of Rissoina (Gastropoda Prosobranchia: Rissoidae) M.J. Faber Zoological Museum, University of Amsterdam, P.O. Box 4766, 1009 AT Amsterdam, The Netherlands The identity of Turbo Bryereus Montagu is established after examining the original, figured type-specimen. It is considered a valid species of Schwartziella (Rissoidae: Rissoininae) from the West Indies. Rissoina scalarella C.B. Adams, R. bermudensis Peile and R. fischeri var. michaudi arc Desjardin considered junior synonyms. “R. bryerea” auctt. is described as new Rissoina s.n. dyscrita n.sp. words: Prosobranchia, Rissoidae, Schwartziella, Rissoina, West Key Gastropoda, taxonomy, Indies. INTRODUCTION In the 1803, described a small of marine mollusc as year Montagu species “Turbo Bryereus”, after specimens from Weymouth, England. He noted that "it is also an occidental shell". Ever since, “T. Bryereus” has generally been considered a Carib- bean of the Rissoina 1840 Rissoina inca species genus d'Orbigny, (type-species d'Orbigny, 1840, by original designation). Members of this genus (and related within the Rissoininae2 do far north genera, not occur as as England; Weymouth as for Rissoina is type-locality bryerea evidently wrong. Regarding the descriptions and figures given by various subsequent authors, two different West Indian rissoinids have been identified as R. bryerea. Following the most recent systematics in Rissoina s.l. (Ponder, 1985), the one figured by Olsson & McGinty (1958), Warmke & Abbott (1961) and De Jong & Coomans(1988) should bet- ter be in the Schwartziella Nevill, 1881 Rissoina orientalis placed genus (type-species Nevill, 1881, by original designation). -

Early Ontogeny and Palaeoecology of the Mid−Miocene Rissoid Gastropods of the Central Paratethys

Early ontogeny and palaeoecology of the Mid−Miocene rissoid gastropods of the Central Paratethys THORSTEN KOWALKE and MATHIAS HARZHAUSER Kowalke, T. and Harzhauser, M. 2004. Early ontogeny and palaeoecology of the Mid−Miocene rissoid gastropods of the Central Paratethys. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 49 (1): 111–134. Twenty−six species of Rissoidae (Caenogastropoda: Littorinimorpha: Rissooidea) are described from the Badenian and Early Sarmatian of 14 localities in Austria and the Czech Republic (Molasse Basin, Styrian Basin, Vienna Basin) and from the Badenian of Coştei (Romania). For the first time, the early ontogenetic skeletal characters of these gastropods are de− scribed. Based on these features an indirect larval development with a planktotrophic veliger could be reconstructed for all investigated Mid−Miocene species. The status of Mohrensterniinae as a subfamily of the Rissoidae is confirmed by the mor− phology of the low conical protoconch, consisting of a fine spirally sculptured embryonic shell and a larval shell which is smooth except for growth lines. Transitions from embryonic shells to larval shells and from larval shells to teleoconchs are slightly thickened and indistinct. Whilst representatives of the subfamily Rissoinae characterise the marine Badenian assem− blages, Mohrensterniinae predominate the Early Sarmatian faunas. We hypothesize that this take−over by the Mohren− sterniinae was triggered by changes in the water chemistry towards polyhaline conditions. Consequently, the shift towards hypersaline conditions in the Late Sarmatian is mirrored by the abrupt decline of the subfamily. Four new species Rissoa costeiensis (Rissoinae) from the Badenian and Mohrensternia hollabrunnensis, Mohrensternia pfaffstaettensis,and Mohrensternia waldhofensis (Mohrensterniinae) from the Early Sarmatian are introduced. -

Worms - World Register of Marine Species 15/01/12 08:52

WoRMS - World Register of Marine Species 15/01/12 08:52 http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxlist WoRMS Taxon list http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxlist 405 matching records, showing records 1-100. Rissoa Freminville in Desmarest, 1814 Rissoa aartseni Verduin, 1985 Rissoa aberrans C. B. Adams, 1850 accepted as Stosicia aberrans (C. B. Adams, 1850) Rissoa albella Lovén, 1846 accepted as Pusillina sarsii (Lovén, 1846) Rissoa albella Alder, 1844 accepted as Rissoella diaphana (Alder, 1848) Rissoa albella rufilabrum Alder accepted as Rissoa lilacina Récluz, 1843 Rissoa albugo Watson, 1873 Rissoa alifera Thiele, 1925 accepted as Hoplopteron alifera (Thiele, 1925) Rissoa alleryi (Nordsieck, 1972) Rissoa angustior (Monterosato, 1917) Rissoa atomus E. A. Smith, 1890 Rissoa auriformis Pallary, 1904 Rissoa auriscalpium (Linnaeus, 1758) Rissoa basispiralis Grant-Mackie & Chapman-Smith, 1971 † accepted as Diala semistriata (Philippi, 1849) Rissoa boscii (Payraudeau, 1826) accepted as Melanella polita (Linnaeus, 1758) Rissoa calathus Forbes & Hanley, 1850 accepted as Alvania beanii (Hanley in Thorpe, 1844) Rissoa cerithinum Philippi, 1849 accepted as Cerithidium cerithinum (Philippi, 1849) Rissoa coriacea Manzoni, 1868 accepted as Talassia coriacea (Manzoni, 1868) Rissoa coronata Scacchi, 1844 accepted as Opalia hellenica (Forbes, 1844) Rissoa costata (J. Adams, 1796) accepted as Manzonia crassa (Kanmacher, 1798) Rissoa costulata Alder, 1844 accepted as Rissoa guerinii Récluz, 1843 Rissoa crassicostata C. B. Adams, 1845 accepted as Opalia hotessieriana (d’Orbigny, 1842) Rissoa cruzi Castellanos & Fernández, 1974 accepted as Alvania cruzi (Castellanos & Fernández, 1974) Rissoa cumingii Reeve, 1849 accepted as Rissoina striata (Quoy & Gaimard, 1833) Rissoa curta Dall, 1927 Rissoa decorata Philippi, 1846 Rissoa deformis G.B. -

Guide to the Systematic Distribution of Mollusca in the British Museum

PRESENTED ^l)c trustee*. THE BRITISH MUSEUM. California Swcademu 01 \scienceb RECEIVED BY GIFT FROM -fitoZa£du^4S*&22& fo<?as7u> #yjy GUIDE TO THK SYSTEMATIC DISTRIBUTION OK MOLLUSCA IN III K BRITISH MUSEUM PART I HY JOHN EDWARD GRAY, PHD., F.R.S., P.L.S., P.Z.S. Ac. LONDON: PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES 1857. PRINTED BY TAYLOR AND FRANCIS, RED LION COURT, FLEET STREET. PREFACE The object of the present Work is to explain the manner in which the Collection of Mollusca and their shells is arranged in the British Museum, and especially to give a short account of the chief characters, derived from the animals, by which they are dis- tributed, and which it is impossible to exhibit in the Collection. The figures referred to after the names of the species, under the genera, are those given in " The Figures of Molluscous Animals, for the Use of Students, by Maria Emma Gray, 3 vols. 8vo, 1850 to 1854 ;" or when the species has been figured since the appear- ance of that work, in the original authority quoted. The concluding Part is in hand, and it is hoped will shortly appear. JOHN EDWARD GRAY. Dec. 10, 1856. ERRATA AND CORRIGENDA. Page 43. Verenad.e.—This family is to be erased, as the animal is like Tricho- tropis. I was misled by the incorrectness of the description and figure. Page 63. Tylodinad^e.— This family is to be removed to PleurobrancMata at page 203 ; a specimen of the animal and shell having since come into my possession. -

The Influence of Ocean Warming on the Provision of Biogenic Habitat by Kelp Species

University of Southampton Faculty of Natural and Environmental Sciences School of Ocean and Earth Sciences The influence of ocean warming on the provision of biogenic habitat by kelp species by Harry Andrew Teagle (BSc Hons, MRes) A thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Southampton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy April 2018 Primary Supervisor: Dr Dan A. Smale (Marine Biological Association of the UK) Secondary Supervisors: Professor Stephen J. Hawkins (Marine Biological Association of the UK, University of Southampton), Dr Pippa Moore (Aberystwyth University) i UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF NATURAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCES Ocean and Earth Sciences Doctor of Philosophy THE INFLUENCE OF OCEAN WARMING ON THE PROVISION OF BIOGENIC HABITAT BY KELP SPECIES by Harry Andrew Teagle Kelp forests represent some of the most productive and diverse habitats on Earth, and play a critical role in structuring nearshore temperate and subpolar environments. They have an important role in nutrient cycling, energy capture and transfer, and offer biogenic coastal defence. Kelps also provide extensive substrata for colonising organisms, ameliorate conditions for understorey assemblages, and generate three-dimensional habitat structure for a vast array of marine plants and animals, including a number of ecologically and commercially important species. This thesis aimed to describe the role of temperature on the functioning of kelp forests as biogenic habitat formers, predominantly via the substitution of cold water kelp species by warm water kelp species, or through the reduction in density of dominant habitat forming kelp due to predicted increases in seawater temperature. The work comprised three main components; (1) a broad scale study into the environmental drivers (including sea water temperature) of variability in holdfast assemblages of the dominant habitat forming kelp in the UK, Laminaria hyperborea, (2) a comparison of the warm water kelp Laminaria ochroleuca and the cold water kelp L. -

FUGRO EMU LIMITED South Wight Maritime

FUGRO EMU LIMITED South Wight Maritime SAC – reef feature attribute survey Job Number: 160087 Natural England Volume 1 of 1 Document Status: Final NATURAL ENGLAND SOUTH WIGHT MARITIME SAC – REEF FEATURE ATTRIBUTE SURVEY SOUTH COAST OF THE ISLE OF WIGHT FUGRO EMU LIMITED South Wight Maritime SAC – reef feature attribute assessment Job Number: 160087 Natural England Volume 1 of 1 Document Status: Final 2 Final Alison Bessell Jo Weir Andy Addleton 15/04/2016 Stefania De Gregorio 1 Draft for Client Alison Bessell Jo Weir Andy Addleton 08/02/2016 review Stefania De Gregorio Rev. Description Prepared Checked Approved Date Fugro Document No. 16/160087/1941 NATURAL ENGLAND SOUTH WIGHT MARITIME SAC – REEF FEATURE ATTRIBUTE SURVEY SOUTH COAST OF THE ISLE OF WIGHT FRONTISPIECE Fugro Document No. 16/160087/1941 NATURAL ENGLAND SOUTH WIGHT MARITIME SAC – REEF FEATURE ATTRIBUTE SURVEY SOUTH COAST OF THE ISLE OF WIGHT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Fugro EMU Limited were contracted by Natural England, to undertake a diving project in the summer to autumn of 2015, to monitor the species composition attributes of subtidal reef features of the South Wight Maritime Special Area of Conservation (SAC) (Contract Number: ECM_42179). The SAC is located off the southern shore of the Isle of Wight, and qualifies as an SAC for Annex I habitat: Reefs, as listed in the EU Habitats Directive. The area encompasses a large range of reef types and associated marine communities, which include limestone, sandstone and chalk. Diving operations were conducted between the 7 and 10 September 2015. The remainder of the week was aborted due to poor weather conditions. -

Subgenus Turboella Gray, 1847, from the Mediterranean And

BASTF.RIA 40: 21-73, 1976 On the systematics of recent Rissoa of the subgenus Turboella Gray, 1847, from the Mediterranean and European Atlantic coasts A. Verduin c/o Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historic Leiden Contents Abstract 22 Introduction 23 Material and methods 24 Terminology 24 Observations and results 25 Rissoa parva and Rissoa interrupta 25 Rissoa dolium 30 Rissoa inconspicua 30 Rissoa radiata 34 Rissoa lineolata 41 Rissoa pulchella 42 Rissoa benzi 45 Rissoa margiminia 46 Rissoa munda 47 Rissoa marginata 50 Summary of discriminating characters of the discussed species 54 Plates 58 Registration of the figured shells 67 Some encountered in aberrant names the collections 67 studied: synonyms References 71 For footnote 1 p.t.o. 22 BASTHRIA, Vol. 40, No. 2-3, 1976 Abstract This is critical evaluation of of the Turboella of the paper a part subgenus Rissoa. The R. (da Costa), R. inconspicua Alder, R. dolium genus species parva Nyst, R. radiata Ph., R. lineolata Mich., R. pulchella Ph., R. benzi (Arad. & M.), R. margiminia (Nords.), R. munda (Monts.), and R. marginata Mich, are retained. There The variability of these species is discussed and illustrated. are two pairs of and sibling species: R. radiata and R. munda; R. pulchella R. marginata. The often the dimensions. partners of each pair are separable only by apical The identity of R. ehrenbergi Ph., R. simplex Ph. and R. obscura Ph. remains unknown. R. radiata balkei n. subsp. is described from the Atlantic coastbetween W. Africa and Bretagne, France. 1 Coan Oct. In contrast to what (1964: 166) implies, Turboella Leach (in Gray, It 4847: 271) is not an available name.