Patient Responses to Research Recruitment and Follow-Up Surveys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministry of Culture Initiative Set to Help Strengthen Qatar's Publishing Industry

16 Monday, January 6, 2020 The Last Word Ministry of Culture initiative set to help strengthen Qatar’s publishing industry sional relations between The programme aims to sophisticated electronic sys- by Minister of Culture and develop the publishing and The inaugural DPFP will host 42 Qatari, Arab publishers and enhance the establish professional rela- tem that allows them to reg- Sports Decision No 51 of distribution industry by set- and foreign publishers from 22 countries concept of intellectual prop- tions between publishers ister their accounts, organ- 2019, with the aim of rais- ting up and participating erty in addition to bringing ise meeting with publishers, ing the professional level of in specialised professional QNA at a two-day forum featur- publishers from around the and enhance the concept exchange ideas, explore op- the publishing and distri- courses, revitalising the DOHA ing seminars from leading world to trade rights for of intellectual property in portunities to acquire and bution industry; promoting cultural movement, coordi- publishing industry experts books and further promot- addition to bringing pub- sell copyright. joint cooperation between nating efforts and positions THE Ministry of Culture and at the Doha International ing cultural exchange. lishers from around the The programme will also publishers and distributors; with Qatari associations, fo- Sports, represented by the Book Fair. For his part, Executive world to trade rights for provide participants with distributing the production rums and cultural centres -

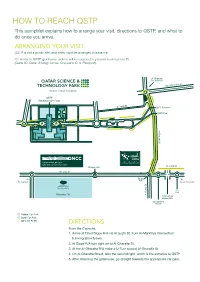

HOW to REACH QSTP This Pamphlet Explains How to Arrange Your Visit, Directions to QSTP, and What to Do Once You Arrive

HOW TO REACH QSTP This pamphlet explains how to arrange your visit, directions to QSTP, and what to do once you arrive. ARRANGING YOUR VISIT QSTP is not a public site, and visits must be arranged in advance. On arrival to QSTP gatehouse visitors will be required to present a valid photo ID. (Qatar ID, Qatar driving license, Company ID or Passport) Al Gharrafa Roundabout Thani Bin Jasim st. QSTP Reception (2nd floor) Al Telal St. QSTP Entrance GE QSTP Exit TION A V CENTRE INNO Al-Gharaffa St. TECH1 TECH2 Al Luqta St. Shaqab R/A Al Luqta St. Slope R/A To Dukhan From Corniche TV R/A Education City Al Huwar St. Al Markhiya Intersection Immigration Flyover Visitor Car Park Staff Car Park GE CAR PARK DIRECTIONS From the Corniche, 1. Arrive at Tilted/Slope R/A via Al Luqta St. from Al-Markhiya Intersection & Immigration flyover. 2. At Slope R/A turn right on to Al-Gharaffa St. 3. At the Al-Gharaffa R/A make a U-Turn toward Al-Gharaffa St. 4. On Al-Gharaffa Street, take the second right, which is the entrance to QSTP. 5. After clearning the gatehouse, go straight towards the appropriate car park. HOW TO REACH QMIC AT QSTP ARRANGING YOUR VISIT QSTP is not a public site, and visits must be arranged in advance. On arrival to QSTP gatehouse visitors will be required to present a valid photo ID. (Qatar ID, Qatar driving license, Company ID or Passport) DIRECTIONS TO QMIC After you pass the main gate: Take the first roundabout straight on the second roundabout Make a U turn Take the second exit towards the parking Enter the parking using the card given by security staff Tech 2 building will be just to your right Park your vehicle and enter through the glass door Use the elevator to reach to the second floor Take slight left and towards the straight corridor infront of you Reach to QMIC office suite 201 on your left hand at the end of the corridor QSTP Reception (2nd floor) Al Telal St. -

Quality of Service Measurements- Mobile Services Network Audit 2012

Quality of Service Measurements- Mobile Services Network Audit 2012 Quality of Service REPORT Mobile Network Audit – Quality of Service – ictQATAR - 2012 The purpose of the study is to evaluate and benchmark Quality Levels offered by Mobile Network Operators, Qtel and Vodafone, in the state of Qatar. The independent study was conducted with an objective End-user perspective by Directique and does not represent any views of ictQATAR. This study is the property of ictQATAR. Any effort to use this Study for any purpose is permitted only upon ictQATAR’s written consent. 2 Mobile Network Audit – Quality of Service – ictQATAR - 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 READER’S ADVICE ........................................................................................ 4 2 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................... 5 2.1 TEAM AND EQUIPMENT ........................................................................................ 5 2.2 VOICE SERVICE QUALITY TESTING ...................................................................... 6 2.3 SMS, MMS AND BBM MEASUREMENTS ............................................................ 14 2.4 DATA SERVICE TESTING ................................................................................... 16 2.5 KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS ...................................................................... 23 3 INDUSTRY RESULTS AND INTERNATIONAL BENCHMARK ........................... 25 3.1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ -

Nearly 1,800 Students from Across Globe Set to Role-Play As Diplomats THIMUN Qatar Conference from January 22 to 25

20 Thursday, December 27, 2018 The Last Word Nearly 1,800 students from across globe set to role-play as diplomats THIMUN Qatar conference from January 22 to 25 TRIBUNE NEWS NETWORK DOHA AS part of its belief in the ca- pacity of Qatar’s youth to be change-makers and thought- leaders, Qatar Foundation (QF), through its Pre-Univer- sity Education mission area, is preparing for the upcoming eighth annual THIMUN Qatar conference, to be held from January 22 to 25, 2019. The Doha-based Model The Doha-based Model United Nations (MUN) conference – the largest in the Middle East – will bring together nearly 1,800 students from over 67 schools across the world to role-play as diplomats and ambassadors. United Nations (MUN) con- ference – the largest in the “Today’s youth is the fu- Over the last few months, liefs, they will also be given the ting for such dialogue to special focus on the current to some of the world’s most Middle East – will bring to- ture of our world and by pro- students have been conduct- unique opportunity to learn happen as the 18th edition of diplomatic crisis in the region. pressing issues. Through its gether nearly 1,800 students viding opportunities for young ing sessions and carrying out from the experts themselves: the Doha Forum brought to- Central to the forum’s many centres, programmes from over 67 schools around people to discuss, negotiate research in order to represent the UNODC representatives,” gether international experts, ethos is the desire to drive and initiatives, QF strives to the world to role-play as dip- and debate, through initiatives their appointed countries. -

QATAR Information Sheet

QATAR Information Sheet © International Affiliate of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2020 Credentialing Verification Authority: Qatar Council for Healthcare Practitioners Communication: Arabic, English Ongoing Nutrition Activities in Qatar 1. National Dietetic Association None at the moment. Related organizations Qatar Diabetes Association • Address: Rawdat Al Khail , Al Muntaza, Doha, State of Qatar • Phone Number: (+974) 44547341 • Website: httPs://qda.org.qa/home/ 2. National Nutrition Programmes/Projects • DeveloPment of Qatar Dietary Guidelines To download PDF coPy: httPs://www.moPh.gov.qa/Admin/Lists/PublicationsAttachments/Attachmen ts/68/MOPH_DIETARY_BOOKLET_ENG.PDF • Several awareness campaigns, such as: o World Food Day § Held on October 16 each year § Aim is to emphasize the need of eradicating hunger, and instilling it as a moral and human responsibility of all § To commemorate the day, Qatar Charity distributed 100,000 meals to refugees and Poor families in Palestine, Turkey, and Lebanon § At Hamad Medical Corporation, awareness booth was also installed in one of its facilities o World Obesity Day § Held on October 28, 2019 at Hamad General Hospital § Led by Bariatric dietitians of Hamad Medical Corporation § The campaign includes various booths installed Presenting food Portion sizes, healthy cooking tiPs and reciPes, information on Fad diets, diet Pre and Post Bariatric surgery, with educational materials distributed, and lecture Presentation on Diet and Obesity o World Diabetes Day § Every November 14 each year § Led by Ministry of Public Health, in cooPeration with Hamad Medical Corporation, Primary Health Care Corporation, Sidra Medicine and Qatar Diabetes Association § Part of Qatar National Diabetes Strategy 2016-2022 § The campaign includes nutrition, Physical activity, and awareness by conducting questionnaires, counselling Patients, conducting workshoPs, and launching of its website 3. -

1 Population 2018 السكان

!_ اﻻحصاءات السكانية واﻻجتماعية FIRST SECTION POPULATION AND SOCIAL STATISTICS !+ الســكان CHAPTER I POPULATION السكان POPULATION يعتﺮ حجم السكان وتوزيعاته املختلفة وال يعكسها Population size and its distribution as reflected by age and sex structures and geographical الﺮكيب النوي والعمري والتوزيع الجغراي من أهم البيانات distribution, are essential data for the setting up of اﻻحصائية ال يعتمد علا ي التخطيط للتنمية .socio - economic development plans اﻻقتصادية واﻻجتماعية . يحتوى هذا الفصل عى بيانات تتعلق بحجم وتوزيع السكان This Chapter contains data related to size and distribution of population by age groups, sex as well حسب ا ل ن وع وفئات العمر بكل بلدية وكذلك الكثافة as population density per zone and municipality as السكانية لكل بلدية ومنطقة كما عكسا نتائج التعداد ,given by The Simplified Census of Population Housing & Establishments, April 2015. املبسط للسكان واملساكن واملنشآت، أبريل ٢٠١٥ The source of information presented in this chapter مصدر بيانات هذا الفصل التعداد املبسط للسكان is The Simplified Population, Housing & واملساكن واملنشآت، أبريل ٢٠١٥ مقارنة مع بيانات تعداد Establishments Census, April 2015 in comparison ٢٠١٠ with population census 2010 تقدير عدد السكان حسب النوع في منتصف اﻷعوام ١٩٨٦ - ٢٠١٨ POPULATION ESTIMATES BY GENDER AS OF Mid-Year (1986 - 2018) جدول رقم (٥) (TABLE (5 النوع Gender ذكور إناث المجموع Total Females Males السنوات Years ١٩٨٦* 247,852 121,227 369,079 *1986 ١٩٨٦ 250,328 123,067 373,395 1986 ١٩٨٧ 256,844 127,006 383,850 1987 ١٩٨٨ 263,958 131,251 395,209 1988 ١٩٨٩ 271,685 135,886 407,571 1989 ١٩٩٠ 279,800 -

Over 900 Mosques, Areas Ready for Eid Al Adha Prayers

MONDAY JULY 19, 2021 DHUL HIJJAH 9, 1442 VOL.14 NO. 5314 QR 2 Fajr: 3:27 am Dhuhr: 11:40 am RAINY Asr: 3:05 pm Maghrib: 6:28 pm HIGH : 38°C LOW : 34 °C Isha: 7:58 pm World 5 Business 7 Sports 12 Merkel pledges to rebuild Qatar sees spike in factory Qatar score four goals unanswered ‘devastated’ flood-hit areas activities in Q2: ValuStrat in dominant win over Grenada Amir exchanges Eid Al Adha greetings Over 900 mosques, with leaders of Arab & Islamic nations QNA greetings with HH Amir of the areas ready for DOHA State of Kuwait Sheikh Nawaf Al Ahmad Al Jaber Al Sabah, HIS Highness the Amir of State and HH Crown Prince Sheikh of Qatar Sheikh Tamim bin Mishal Al Ahmad Al Jaber Al Hamad Al Thani exchanged Sabah on the advent of the Eid Al Adha prayers greetings with a number of blessed Eid Al Adha. leaders of Arab and Islamic HH the Amir also ex- countries on the advent of the changed greetings with HM Eid Al Adha blessed Eid Al Adha, during King Mohammed VI of the phone calls on Sunday evening. Kingdom of Morocco, HE Pres- prayer will take HH the Amir exchanged ident of the Republic of Tuni- place at 5:10 am greetings with the Custodian sia Kais Saied, HE President of the Two Holy Mosques King of the People’s Democratic Re- on Tuesday Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud public of Algeria Abdelmadjid of the Kingdom of Saudi Ara- Tebboune, HE President of the bia on the advent of the blessed Republic of Iraq Dr Barham QNA & TNN Eid AlAdha, in a phone call HH Salih, and HE President of DOHA the Amir held on Sunday. -

1 Population 2015 السكان

!_ اﻻحصاءات السكانية واﻻجتماعية FIRST SECTION POPULATION AND SOCIAL STATISTICS !+ الســكان CHAPTER I POPULATION السكان POPULATION يعتﺮ حجم السكان وتوزيعاته املختلفة وال يعكسها Population size and its distribution as reflected الﺮكيب النوي والعمري والتوزيع الجغراي من أهم by age and sex structures and geographical البيانات اﻻحصائية ال يعتمد علا ي التخطيط distribution, are essential date for the setting up للتنمية اﻻقتصادية واﻻجتماعية . .of economic and social development plans يحتوى هذا الفصل عى بيانات تتعلق بحجم وتوزيع السكان حسب ا ل ن وع وفئات العمر بكل بلدية وكذلك This Chapter contains data related to size and الكثافة السكانية لكل بلدية ومنطقة كما عكسا نتائج distribution of population by age groups, sex as التعداد املبسط للسكان واملساكن واملنشآت، أبريل well as population density per zone and municipality as given by Census Population, ٢٠١٥ .Housing & Establishments, April 2015 مصدر بيانات هذا الفصل التعداد املبسط للسكان The source of information presented in this واملساكن واملنشآت، أبريل ٢٠١٥ مقارنة مع بيانات & chapter is the Population, Housing تعداد ٢٠١٠ Establishments Census April 2015 in comparison with population census 2010 تقدير عدد السكان في منتصف اﻷعوام ١٩٨٦ - ٢٠١٥ POPULATION ESTIMATE AS OF MIDDLE 1986 - 2015 جدول رقم (٥) (TABLE (5 النوع Gender ذكور إناث المجموع Total Females Males السنوات Years ١٩٨٦* 247,852 121,227 369,079 *1986 ١٩٨٦ 250,328 123,067 373,395 1986 ١٩٨٧ 256,844 127,006 383,850 1987 ١٩٨٨ 263,958 131,251 395,209 1988 ١٩٨٩ 271,685 135,886 407,571 1989 ١٩٩٠ 279,800 140,979 420,779 1990 ١٩٩١ 288,600 145,772 434,372 -

Medical Policy Agreement

SECTION C: QLM QATAR PREFERRED PROVIDER NETWORK – EMERALD PLUS You can choose from the listed provider which can meet with your members’ requirements within the area of cover of your selected plan: CONTACT DETAILS PROVIDER NAME TELEPHONE No. FAX No. PROVIDER TYPE ADDRESS HOSPITALS AL AHLI HOSPITAL 44898000 44898989 In-Outpatient Bin Omran Street Hilal West Area near The Mall R/A, In-Outpatient AL EMADI HOSPITAL 44666009 44678340 along D Ring Road AL MAGHRABI EYE, ENT & D Ring Road near Safeer Center Opp to In-Outpatient DENTAL CENTER 44238888 44646377 Hassan Al-Abdulla Dental Center C Ring Road near Andaloos Petrol In-Outpatient AMERICAN HOSPITAL 44421999 44424888 Station, Muntazah DOHA CLINIC HOSPITAL 44384333 44384395 In-Outpatient New Mirqab Street, Al Fareej Al Nasr Opposite to American Hospital, C Ring In-Outpatient TURKISH HOSPITAL 44992444 Road, New Salata ASTER HOSPITAL 44440499 In-Outpatient D Ring Road, behind Family Food Center HAMAD HOSPITAL & PRIMARY HEALTH CARE CENTERS On Re-imbursement Basis with (NO) co-insurance Doha POLYCLINICS AL-SAFA POLYCLINIC 44322448 44360572 Outpatient # 39 Al-Kinana St., Al-Nasr AL JAZEERA MEDICAL CENTRE 44351155 44351128 Outpatient Al Jaidah Building, Gulf Street AL JAZEERA MEDICAL CENTRE - MUAITHER BRANCH 44886464 44886363 Outpatient Building No. 312, Furousiya Street AL JAZEERA MEDICAL CENTRE - Building No. 24, Al Seliya Street, BUSIDRA BRANCH 44446062 Outpatient Maither South AL JAZEERA MEDICAL CENTRE - WAKRAH BRANCH 44446030 44140051 Outpatient Building No. 1890, Al Wakrah Road AL MANSOUR -

Project Reference List in Qatar LIST of PROJECTS SUPPLIED in QATAR

6.2 -Project reference list in Qatar LIST OF PROJECTS SUPPLIED IN QATAR S. # Description of work (Project Name) Company Amount/ QR 1 C188 Project Al Tawfeeq 500,000.00 2 C-62 Project Madinat Khalifa Sewers. Medgulf 600,000.00 3 Project HC 76/1 & 2 MARBU 200,000.00 4 Hamad Mech. Regiment, Duhail Shannon 110,000.00 5 Project C-355-1 Al Teyseer 120,000.00 6 Project HC 76/4 Naame 300,000.00 7 Project HC 76/3 Shannon 170,000.00 8 Al Wajba Al Tawfeeq 150,000.00 9 C-285SSHP Infrastructure KBAS 370,000.00 10 Al Najadh & Al Saad Road JBK 400,000.00 11 Rumailah Road HABA 290,000.00 12 C-358 Al Tawfeeq 100,000.00 13 C-265 Al Darwish 25,000.00 14 Tareq Bin Ziyad N.I.C.C. 142,000.00 15 MS-103 Al Obeidly & Gulf 310,000.00 16 Civil Project 368 ACEC 80,000.00 17 Civil Project 273 Al Tawfeeq 160,000.00 18 N. Camp Project 2B Temalco 120,000.00 19 Block 1200 Project (1+2) Darwish Engg. 600,000.00 20 Block 1300 Project C.E.C. 600,000.00 21 Civil Project 368 A.C.E.C. 70,000.00 22 C.P. 231 Manco 7,000.00 23 Al Nejada Complex MIDMAC 13,000.00 Page 1 of 24 S. # Description of work (Project Name) Company Amount/ QR 24 C.P. 357 TEMALCO 30,000.00 25 Central Prison Al Rehab 10,000.00 26 Block 3000 Project Al Tayseer 1,200,000.00 27 West Corniche Park Al Rehab 30,000.00 28 Doha Air Base C-406/2 N.I.C.C. -

PM, Kuwait Deputy PM Inaugurate Sabah Al Ahmad Corridor O 29Km-Long Corridor Is One of the Largest Road Projects Executed by Ashghal

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 30-year total CHI Al Shaqab investment in equestrian gas to reach $10tn extravaganza gets by 2050: GECF underway today published in QATAR since 1978 THURSDAY Vol. XXXXII No. 11835 February 25, 2021 Rajab 13, 1442 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir meets Kuwait’s Deputy PM and Defence Minister PM, Kuwait Deputy PM inaugurate Sabah Al Ahmad Corridor O 29km-long Corridor is one of the largest road projects executed by Ashghal By Shafeeq Alingal the project. At the beginning of the Airport (HIA) to Al Shamal Road while Staff Reporter inaugural event, a short video that intersecting with 15 main roads includ- highlighted the life and contributions ing Ras Bu Abboud Street, Industrial of Sheikh Sabah was screened. Area Road, Salwa Road, Al Waab Street t a grand ceremony, the Sabah Another fi lm shed light on the dis- and Al Rayyan Road and connecting 25 Al Ahmad Corridor, described tinct features of Sabah Al Ahmad Cor- residential neighbourhoods with many His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met yesterday at the Amiri Diwan Off ice with Deputy Prime Aas a vital artery in the heart ridor, a prestigious project of the Public commercial, educational and health Minister and Defence Minister of the sisterly State of Kuwait Sheikh Hamad Jaber al-Ali al-Sabah and the accompanying of Doha, was inaugurated by HE the Works Authority (Ashghal), as one of facilities. delegation, on the occasion of his visit to the country to attend the inaugural ceremony of Sabah Al Ahmad Corridor. -

Providers' Network - General

Providers' Network - General HOSPITALS Provider Name Phone Fax Address American Hospital 44421999 44424888 C-Ring road next to Ministry of Labor Doha Clinic Hospital 44384333 44327303 Al Nasr, Al Merqab street MEDICAL CENTERS Provider Name Phone Fax Address Apollo Clinic 44418441 44418442 Al Mansoura Qatar Medical Center 44440606 44353281 Salwa Road, near Midmac bridge ICON Medical Center 40191200 44414945 Al Najma Area, Al Arab St.Buliding C Aster Medical Centre - Al Rafa Polyclinic- Al Ghanim 44129910 44875166 Al Ghanim near Doha Central Bus Station Aster Medical Centre - Al Rafa Polyclinic - Industrial Area 44604449 44500175 Industrial Area-Qatar Airways Building Aster Medical Centre - Al Rafa Polyclinic - Al Khor 44214338 44214339 Al Khor, op. Mc. Donalds Aster Medical Centre Plus - Al Rafa Polyclinic - C Ring road 40219777 40219779 C-Ring road, near Ministry Of Labor, Muntazah Aster Medical Centre Plus - Medcare Clinic - Al Hilal 44550755 44550677 Al Hilal, near Woqood Petrol Station Aster Medical Centre Plus - Wellcare Clinic - Al Rayyan 44821153 44175277 Al Rayyan, near Al Shafi mosque Dr. Mohammad Zbeib Polyclinic (Excluding Dental clinics) 44685544 44685544 Abu Hamour, Halloul street Elaj Medical Center 44430055 44315119 Salwa Road, behind Radisson Hotel Kims Medical Center 44631864 44631534 Al Wakra Naseem Al Rabeeh Medical Center 44652121 44567167 D-Ring road Future Medical Center 44510051 44516651 Al Waab, op. Villagio Mall Royal Medical Center 44502050 44655400 Muntazah street Royal Medical Center - Gharrafa 44602060 40391476 Al Maszhabiya Street, Gharrafa Al Hayat Medical Center (Excluding Dental Clinics) 44422566 44325641 Al Waab Al Esraa Medical Center 44989811 44989833 Al Gharafa, near Landmark Mall Atlas Medical Center - Barwa 44153222 44632003 Barwa village, Wakra Road Atlas Polyclnic - Industrial Area 44554001 44554002 Industrial Area, St.