Autumn/Winter 2020 ������������������ �����������������

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Food, Great Stories from Korea

GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIE FOOD, GREAT GREAT A Tableau of a Diamond Wedding Anniversary GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS This is a picture of an older couple from the 18th century repeating their wedding ceremony in celebration of their 60th anniversary. REGISTRATION NUMBER This painting vividly depicts a tableau in which their children offer up 11-1541000-001295-01 a cup of drink, wishing them health and longevity. The authorship of the painting is unknown, and the painting is currently housed in the National Museum of Korea. Designed to help foreigners understand Korean cuisine more easily and with greater accuracy, our <Korean Menu Guide> contains information on 154 Korean dishes in 10 languages. S <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Tokyo> introduces 34 excellent F Korean restaurants in the Greater Tokyo Area. ROM KOREA GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES FROM KOREA The Korean Food Foundation is a specialized GREAT FOOD, GREAT STORIES private organization that searches for new This book tells the many stories of Korean food, the rich flavors that have evolved generation dishes and conducts research on Korean cuisine after generation, meal after meal, for over several millennia on the Korean peninsula. in order to introduce Korean food and culinary A single dish usually leads to the creation of another through the expansion of time and space, FROM KOREA culture to the world, and support related making it impossible to count the exact number of dishes in the Korean cuisine. So, for this content development and marketing. <Korean Restaurant Guide 2011-Western Europe> (5 volumes in total) book, we have only included a selection of a hundred or so of the most representative. -

Amy Howlett Amychowlett.Com Omitted – Just Add the Lemon Zest, Garlic, Thyme and Ground Coriander at the Stage of Sweating Down the Onions for the Pork Cheeks

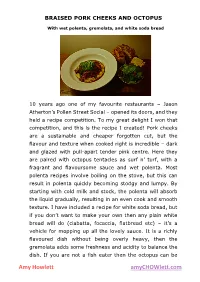

BRAISED PORK CHEEKS AND OCTOPUS With wet polenta, gremolata, and white soda bread 10 years ago one of my favourite restaurants – Jason Atherton’s Pollen Street Social – opened its doors, and they held a recipe competition. To my great delight I won that competition, and this is the recipe I created! Pork cheeks are a sustainable and cheaper forgotten cut, but the flavour and texture when cooked right is incredible – dark and glazed with pull-apart tender pink centre. Here they are paired with octopus tentacles as surf n’ turf, with a fragrant and flavoursome sauce and wet polenta. Most polenta recipes involve boiling on the stove, but this can result in polenta quickly becoming stodgy and lumpy. By starting with cold milk and stock, the polenta will absorb the liquid gradually, resulting in an even cook and smooth texture. I have included a recipe for white soda bread, but if you don’t want to make your own then any plain white bread will do (ciabatta, focaccia, flatbread etc) – it’s a vehicle for mopping up all the lovely sauce. It is a richly flavoured dish without being overly heavy, then the gremolata adds some freshness and acidity to balance the dish. If you are not a fish eater then the octopus can be Amy Howlett amyCHOWlett.com omitted – just add the lemon zest, garlic, thyme and ground coriander at the stage of sweating down the onions for the pork cheeks. Similarly, for any pescetarians the octopus quantity can be increased, cooking the onions and marinade ingredients from the pork cheek recipe before adding the marinated octopus. -

Shelf Life Validation of Marinated and Frozen Chicken Tenderloins by John Gregory Rehm a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Facult

Shelf Life Validation of Marinated and Frozen Chicken Tenderloins by John Gregory Rehm A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama August 8, 2020 Approved by Dr. Christy Bratcher, Chair, Professor of Animal Science Dr. Jason Sawyer, Associate Professor of Animal Science Dr. Amit Morey, Assistant Professor of Poultry Science Abstract It is immensely important for producers and restaurants to know the shelf life of a meat product. If a consumer eats a product that is rancid it could impact a restaurant’s reputation. The objective of this study is to validate the shelf life of marinated and frozen chicken tenders. The treatments were the age of the chicken tender after harvest, which were 4 days of age (DA), DA5, DA6, DA7 and DA8. Spoilage organisms, pH and instrumental color (L*, a*, b*) were measured to assess the shelf life of bulk-packaged bags of chicken tenders. The microbial analysis analyzed the growth of aerobic, psychotrophic and lactobacilli bacteria. Each treatment contained 47.63 kg of chicken. Chicken was sampled fresh then tumbled in a marinade that contained water, salt, modified corn starch and monosodium glutamate. After marinating, the chicken tenders were sampled (0 hours) and the other remaining tenders were put into a blast freezer (-25ºC). After freezing, the chicken thawed in a cooler (2.2ºC) for 132 hours (h) and was sampled at 36h, 60h, 84h, 108h, 132h. After marinating the chicken tenders, each treatment decreased in the aerobic count and the psychotroph count except for DA4. -

Good Manufacturing Practices For

Good Manufacturing Practices for Fermented Dry & Semi-Dry Sausage Products by The American Meat Institute Foundation October 1997 ANALYSIS OF MICROBIOLOGICAL HAZARDS ASSOCIATED WITH DRY AND SEMI-DRY SAUSAGE PRODUCTS Staphylococcus aureus The Microorganism Staphylococcus aureus is often called "staph." It is present in the mucous membranes--nose and throat--and on skin and hair of many healthy individuals. Infected wounds, lesions and boils are also sources. People with respiratory infections also spread the organism by coughing and sneezing. Since S. aureus occurs on the skin and hides of animals, it can contaminate meat and by-products by cross-contamination during slaughter. Raw foods are rarely the source of staphylococcal food poisoning. Staphylococci do not compete very well with other bacteria in raw foods. When other competitive bacteria are removed by cooking or inhibited by salt, S. aureus can grow. USDA's Nationwide Data Collection Program for Steers and Heifers (1995) and Nationwide Pork Microbiological Baseline Data Collection Program: Market Hogs (1996) reported that S. aureus was recovered from 4.2 percent of 2,089 carcasses and 16 percent of 2,112 carcasses, respectively. Foods high in protein provide a good growth environment for S. aureus, especially cooked meat/meat products, poultry, fish/fish products, milk/dairy products, cream sauces, salads with ham, chicken, potato, etc. Although salt or sugar inhibit the growth of some microorganisms, S. aureus can grow in foods with low water activity, i.e., 0.86 under aerobic conditions or 0.90 under anaerobic conditions, and in foods containing high concentrations of salt or sugar. S. -

Effect of Different Marinade Treatments on Survival and Morphology of Pathogens in Beef Jerky

EFFECT OF DIFFERENT MARINADE TREATMENTS ON SURVIVAL AND MORPHOLOGY OF PATHOGENS IN BEEF JERKY ________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri ________________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science ________________________________________________________________________ by SANDEEP KHURANA Dr. Andrew D. Clarke, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2009 The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled EFFECT OF DIFFERENT MARINADE TREATMENTS ON SURVIVAL AND MORPHOLOGY OF PATHOGENS IN BEEF JERKY Presented by Sandeep Khurana A candidate for the degree of Master of Science And hereby certify that, in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. _____________________________________________________________ Andrew D. Clarke, Ph.D., Department of Food Science _____________________________________________________________ Carol L. Lorenzen, Ph.D., Department of Animal Science _____________________________________________________________ Azlin Mustapha, Ph.D., Department of Food Science _____________________________________________________________ Ingolf Gruen, Ph.D., Department of Food Science _____________________________________________________________ Mark Ellersieck, Ph.D., Department of Statistics Dedicated to my Parents Sh. Krishan Gopal Khurana And Smt. Raj Kumari Khurana ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with immense -

Operating and Installation Instructions Steam Oven

Operating and installation instructions Steam oven To avoid the risk of accidents or damage to the appliance it is essential to read these instructions before it is installed and used for the first time. en-HK, SG M.-Nr. 09 854 980 Contents Warning and Safety instructions .......................................................................... 7 Caring for the environment ................................................................................. 15 Overview ............................................................................................................... 16 Steam oven front view ........................................................................................... 16 Accessories supplied............................................................................................. 17 Controls ................................................................................................................ 18 Sensor controls...................................................................................................... 19 Touch display ......................................................................................................... 20 Symbols ............................................................................................................ 21 Operation ............................................................................................................... 22 Description of functions...................................................................................... 24 Water container..................................................................................................... -

Culinary Arts 3 Final Study Guide

Name: _______________________________________ Culinary Arts 3 Final Study Guide Food Sanitation (Chapters 5, 6, 7) 1. Define: a. Bacteria: b. Sanitation: c. Food borne illness: d. pH: 2. Food cannot be left out more than this many hours? 3. How should hot food be handled? 4. What is cross-contamination? Knife skills and Cuts (Chapter 8 and 9) 5. Define the following terms related to cuts: a. Mincing: b. Batonnet: c. Slices: d. Julienne: e. Rondelle: f. Chiffonade: g. Concasse: h. Mirepoix: i. Mise en place: j. White mirepoix: 6. Where should your hand be when you are handling a French knife? 7. What should you do with your guiding hand? Seasonings and Flavorings (Chapter 13 and 14) 8. What is clarified butter? 9. Describe the following spices: a. White pepper: b. Herbs: c. Cayenne pepper: d. Spices: e. Olive: f. Relish: g. Cornmeal: h. Breadcrumbs: i. Brown sugar: j. Cornstarch: k. Tomato paste: Cooking Techniques (Chapter 15) 10. Define the following cooking techniques a. Poach: b. Cooking: c. Sweating: d. Roasting: e. Gelatinization: f. Caramelization: g. Steaming: 11. When sugars burn what is created? 12. What happens to connective tissue when meat is cooked? 13. Microwaves cook with what? 14. What does convection mean? 15. What does conduction mean? Desserts (Chapter 40-43) 16. Define the following terms associated with desserts: a. Blind baking: b. Sweet dough: c. Flakey pie dough: d. Mealy pie dough: e. Puff pastry: f. Short dough: 17. What type of liquid should you make when preparing pie dough? 18. What happens to a pie crust when it is worked with too much? 19. -

Ancient) Bodies: the Potters’ Sensory Experiences and the Firing of Red, Black and Purple Greek Vases

Article Bringing Back the (Ancient) Bodies: The Potters’ Sensory Experiences and the Firing of Red, Black and Purple Greek Vases Sanchita Balachandran 1,2 1 The Johns Hopkins Archaeological Museum, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Near Eastern Studies, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA Received: 27 March 2019; Accepted: 27 May 2019; Published: 4 June 2019 Abstract: The study of Athenian black‐figure and red‐figure ceramics is haunted by nearly a thousand “hands” of the artisans thought to be responsible for their painted images. But what of the bodies attached to those hands? Who were they? Given the limited archaeological and epigraphic evidence for these ancient makers, this study attempts to recover their physical bodies through the ceramics production process—specifically the firing of vessels—as a communal activity potentially including a large cast of participants including craftsmen and craftswomen, metics, freed people and slaves. Using an experimental archaeology approach, I argue that we can begin to approach the sensory experiences of ancient potters and painters as they produced all the colored surfaces (and not only images) that endure on Greek vases. I propose a four‐stage sensory firing in combination with the three‐stage chemical firing process known for the production of Athenian ceramics, suggesting that each stage—and the colors produced at each stage—had their own “sensory signatures.” Examining extant vases with this awareness of the bodily experience of their ancient makers has the potential to bring back these ancient bodies, moving us beyond the limiting narrative of a single hand wielding a paint brush. -

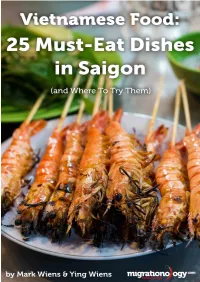

25 Vietnamese Foods

Table of Contents Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 Where to stay in Saigon? ��������������������������������������������������� 5 How You Can Help ������������������������������������������������������������� 6 1� Bánh mì �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 2. Ốp la ����������������������������������������������������������������������������� 10 3. Phở ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 12 4� Bún riêu ������������������������������������������������������������������������ 15 5. Bún mắm ���������������������������������������������������������������������� 17 6. Bún bò Huế������������������������������������������������������������������� 19 7. Bún mọc ����������������������������������������������������������������������� 21 8. Hủ tiếu Nam Vang �������������������������������������������������������� 23 9. Bún chả ������������������������������������������������������������������������ 26 10� Bánh canh cua������������������������������������������������������������ 28 11. Bún thịt nướng ������������������������������������������������������������ 30 12. Bánh tằm bì ���������������������������������������������������������������� 32 13. Bánh cuốn ������������������������������������������������������������������ 34 14� Bánh xèo �������������������������������������������������������������������� 36 15. Bánh khọt ������������������������������������������������������������������� 38 16. Bột chiên��������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Culinary Foundations Chef Randy Cheramie with William R

Culinary Foundations Chef Randy Cheramie With William R. Thibodeaux Ph.D. ii | Culinary Foundations Culinary Foundations | iii Culinary Foundations Chef Randy Cheramie With William R. Thibodeaux Ph.D. iv | Culinary Foundations Culinary Foundations | v Contents Preface ix Culinary Foundations Chapter 1: Professionalism and Sauté 1 Chapter 2: Recipe conversions and Braising 27 Chapter 3: Lab - Mise en Place 33 Chapter 4: Food Presentation, Standards, and Grilling 41 Chapter 5: Emulsions and Steaming 69 Chapter 6: Cajun Creole Cuisine and Roux 75 Chapter 7: The Menu and Poaching 87 Chapter 8: Frying 99 Chapter 9: Flavor and Taste 105 Chapter 10: Breakfast and Roasting 151 Notes: 175 Glossary: 179 Appendix: 211 Kitchen Weights & measurements 213 Measurement and Conversion Charts 215 Basic Cooking Methods 217 Knife Cuts 224 Professional Associations 225 vi | Culinary Foundations Culinary Foundations | vii Limit of Liability/disclaimer of warranty and Safety: The user is expressly advised to consider and use all safety precautions described in this book or that might be indicated by undertaking the activities described in this book. Common sense must also be used to avoid all potential hazards and, in particular, to take relevant safety precautions concerning likely or known hazards involving food preparation, or in the use of the procedures described in this book. In addition, while many rules and safety precautions have been noted throughout the book, users should always have adult supervision and assistance when working in a kitchen or lab. Any use of or reliance upon this book is at the user's own risk. While the information contained in this book has been compiled from sources believed to be reliable and correct at the time of original publication, neither the publisher nor the author makes any warranty, express or implied, with respect to the use of any techniques, suggestions, and ideas disclosed in this book. -

Identifying and Controlling Food Safety Risks at Shell Egg Operations

Identifying and Controlling Food Safety Risks at Shell Egg Operations Patricia A. Curtis & Kenneth E. Anderson Evaluation of egg safety begins when the egg is laid. To conduct a thorough risk analysis the risk assessment must begin at lay and continue through to consumption of the egg by the consumer. The goal of this publication is to provide guidance in evaluating risk from farm to consumer. The risk analysis guidance will provide some research results that will aid in risk analysis for each production and processing step. The layers, production environment, egg temperature (initial and throughout processing and storage), and wash water pH and temperature play key roles in reducing microbial growth in shell eggs and should be key in developing an egg safety plan. We have compiled data from published research related to the shell egg production and processing environment, which could be helpful when developing an egg safety plan. Board and Tranter noted that shell eggs can acquire bacteria from every surface they contact (Board and Tranter 1995). Unlike our earlier publication on this topic, this publication includes the layer house and the processing area. It is important to consider all risks associated with the egg. Many of today’s operations are inline and, therefore, a true shell egg risk assessment should evaluate the risks associated with the egg production as well as the egg processing areas. However, with the shift to more off-line and cage-free production systems, a thorough risk assessment should be done for the entire production through processing. Salmonella Enteritidis (SE) is an organism of concern for the layer industry. -

Food for Thought. Curriculum Projects Developed by 1998 Seminar Participants

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 050 SO 030 826 AUTHOR Tiede, Lynn M. TITLE Food for Thought. Curriculum Projects Developed by 1998 Seminar Participants. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad 1998 (India). INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. SPONS AGENCY United States Educational Foundation in India. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 302p.; Document contains many pages reproduced from serials and newspapers. The quality of reproduction is often poor and text is occasionally cropped. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; Cultural Background; *Cultural Context; Curriculum Development; Developing Nations; *Eating Habits; *Food; Foreign Countries; Global Education; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Student Educational Objectives IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *India ABSTRACT While leaders in India have been slower than other non-Western nations to encourage the sales of Western fast food products, signs of these foods are present in larger cities like Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras. This unit of study is a series of lessons designed to introduce junior high school or high school students to various aspects of the culture, religion, history, economy, and political structures of India. The unit's lessons, however, center around food as a method of introducing the particular objective. Pointing out that Indians, as they meet the continuing challenges of feeding nearly 1 billion people, can learn from U.S. mistakes in "modernizing" their diets and attitudes towards food. The unit's materials seek to help children to begin learning these lessons. The lessons can be given individually or collectively as part of a unit.