Virender Sehwag and Cricket's Existential Anxiety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captain Cool: the MS Dhoni Story

Captain Cool The MS Dhoni Story GULU Ezekiel is one of India’s best known sports writers and authors with nearly forty years of experience in print, TV, radio and internet. He has previously been Sports Editor at Asian Age, NDTV and indya.com and is the author of over a dozen sports books on cricket, the Olympics and table tennis. Gulu has also contributed extensively to sports books published from India, England and Australia and has written for over a hundred publications worldwide since his first article was published in 1980. Based in New Delhi from 1991, in August 2001 Gulu launched GE Features, a features and syndication service which has syndicated columns by Sir Richard Hadlee and Jacques Kallis (cricket) Mahesh Bhupathi (tennis) and Ajit Pal Singh (hockey) among others. He is also a familiar face on TV where he is a guest expert on numerous Indian news channels as well as on foreign channels and radio stations. This is his first book for Westland Limited and is the fourth revised and updated edition of the book first published in September 2008 and follows the third edition released in September 2013. Website: www.guluzekiel.com Twitter: @gulu1959 First Published by Westland Publications Private Limited in 2008 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland and the Westland logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Text Copyright © Gulu Ezekiel, 2008 ISBN: 9788193655641 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. -

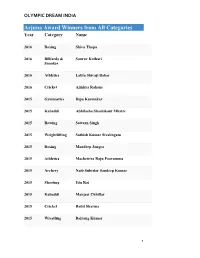

Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name

OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA Arjuna Award Winners from All Categories Year Category Name 2016 Boxing Shiva Thapa 2016 Billiards & Sourav Kothari Snooker 2016 Athletics Lalita Shivaji Babar 2016 Cricket Ajinkya Rahane 2015 Gymnastics Dipa Karmakar 2015 Kabaddi Abhilasha Shashikant Mhatre 2015 Rowing Sawarn Singh 2015 Weightlifting Sathish Kumar Sivalingam 2015 Boxing Mandeep Jangra 2015 Athletics Machettira Raju Poovamma 2015 Archery Naib Subedar Sandeep Kumar 2015 Shooting Jitu Rai 2015 Kabaddi Manjeet Chhillar 2015 Cricket Rohit Sharma 2015 Wrestling Bajrang Kumar 1 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2015 Wrestling Babita Kumari 2015 Wushu Yumnam Sanathoi Devi 2015 Swimming Sharath M. Gayakwad (Paralympic Swimming) 2015 RollerSkating Anup Kumar Yama 2015 Badminton Kidambi Srikanth Nammalwar 2015 Hockey Parattu Raveendran Sreejesh 2014 Weightlifting Renubala Chanu 2014 Archery Abhishek Verma 2014 Athletics Tintu Luka 2014 Cricket Ravichandran Ashwin 2014 Kabaddi Mamta Pujari 2014 Shooting Heena Sidhu 2014 Rowing Saji Thomas 2014 Wrestling Sunil Kumar Rana 2014 Volleyball Tom Joseph 2014 Squash Anaka Alankamony 2014 Basketball Geetu Anna Jose 2 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2014 Badminton Valiyaveetil Diju 2013 Hockey Saba Anjum 2013 Golf Gaganjeet Bhullar 2013 Athletics Ranjith Maheshwari (Athlete) 2013 Cricket Virat Kohli 2013 Archery Chekrovolu Swuro 2013 Badminton Pusarla Venkata Sindhu 2013 Billiards & Rupesh Shah Snooker 2013 Boxing Kavita Chahal 2013 Chess Abhijeet Gupta 2013 Shooting Rajkumari Rathore 2013 Squash Joshna Chinappa 2013 Wrestling Neha Rathi 2013 Wrestling Dharmender Dalal 2013 Athletics Amit Kumar Saroha 2012 Wrestling Narsingh Yadav 2012 Cricket Yuvraj Singh 3 OLYMPIC DREAM INDIA 2012 Swimming Sandeep Sejwal 2012 Billiards & Aditya S. Mehta Snooker 2012 Judo Yashpal Solanki 2012 Boxing Vikas Krishan 2012 Badminton Ashwini Ponnappa 2012 Polo Samir Suhag 2012 Badminton Parupalli Kashyap 2012 Hockey Sardar Singh 2012 Kabaddi Anup Kumar 2012 Wrestling Rajinder Kumar 2012 Wrestling Geeta Phogat 2012 Wushu M. -

Parliament of India R a J Y a S a B H a Committees

Com. Co-ord. Sec. PARLIAMENT OF INDIA R A J Y A S A B H A COMMITTEES OF RAJYA SABHA AND OTHER PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES AND BODIES ON WHICH RAJYA SABHA IS REPRESENTED (Corrected upto 4th September, 2020) RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI (4th September, 2020) Website: http://www.rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] OFFICERS OF RAJYA SABHA CHAIRMAN Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu SECRETARY-GENERAL Shri Desh Deepak Verma PREFACE The publication aims at providing information on Members of Rajya Sabha serving on various Committees of Rajya Sabha, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees, Joint Committees and other Bodies as on 30th June, 2020. The names of Chairmen of the various Standing Committees and Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees along with their local residential addresses and telephone numbers have also been shown at the beginning of the publication. The names of Members of the Lok Sabha serving on the Joint Committees on which Rajya Sabha is represented have also been included under the respective Committees for information. Change of nominations/elections of Members of Rajya Sabha in various Parliamentary Committees/Statutory Bodies is an ongoing process. As such, some information contained in the publication may undergo change by the time this is brought out. When new nominations/elections of Members to Committees/Statutory Bodies are made or changes in these take place, the same get updated in the Rajya Sabha website. The main purpose of this publication, however, is to serve as a primary source of information on Members representing various Committees and other Bodies on which Rajya Sabha is represented upto a particular period. -

Mahendra Singh Dhoni Exemplified the Small-Town Spirit and the Killer Instinct of Jharkhand by Ullekh NP

www.openthemagazine.com 50 31 AUGUST /2020 OPEN VOLUME 12 ISSUE 34 31 AUGUST 2020 CONTENTS 31 AUGUST 2020 7 8 9 14 16 18 LOCOMOTIF INDRAPRASTHA MUMBAI NOTEBOOK SOFT POWER WHISPERER OPEN ESSAY Who’s afraid of By Virendra Kapoor By Anil Dharker The Gandhi Purana By Jayanta Ghosal The tree of life Facebook? By Makarand R Paranjape By Srinivas Reddy By S Prasannarajan S E AG IM Y 22 THE LEGEND AND LEGACY OF TT E G MAHENDRA SINGH DHONI A cricket icon calls it a day By Lhendup G Bhutia 30 A WORKING CLASS HERO He smiled as he killed by Tunku Varadarajan 32 CAPTAIN INDIA It is the second most important job in the country and only the few able to withstand 22 its pressures leave a legacy By Madhavankutty Pillai 36 DHONI CHIC The cricket story began in Ranchi but the cultural phenomenon became pan-Indian By Kaveree Bamzai 40 THE PASSION OF THE BOY FROM RANCHI Mahendra Singh Dhoni exemplified the small-town spirit and the killer instinct of Jharkhand By Ullekh NP 44 44 The Man and the Mission The new J&K Lt Governor Manoj Sinha’s first task is to reach out and regain public confidence 48 By Amita Shah 48 Letter from Washington A Devi in the Oval? By James Astill 54 58 64 66 EKTA KAPOOR 2.0 IMPERIAL INHERITANCE STAGE TO PAGE NOT PEOPLE LIKE US Her once venerated domestic Has the empire been the default model On its 60th anniversary, Bangalore Little Streaming blockbusters goddesses and happy homes are no for global governance? Theatre produces a collection of all its By Rajeev Masand longer picture-perfect By Zareer Masani plays performed over the decades By Kaveree Bamzai By Parshathy J Nath Cover photograph Rohit Chawla 4 31 AUGUST 2020 OPEN MAIL [email protected] EDITOR S Prasannarajan LETTER OF THE WEEK MANAGING EDITOR PR Ramesh C EXECUTIVE EDITOR Ullekh NP Congratulations and thanks to Open for such a wide EDITOR-AT-LARGE Siddharth Singh DEPUTY EDITORS Madhavankutty Pillai range of brilliant writing in its Freedom Issue (August (Mumbai Bureau Chief), 24th, 2020). -

PDF 1St April 2018 1. Permanent Indus Commission Meet Begins in Delhi the Indian Delegation for the Annual Meeting Comprises

PDF 1st April 2018 1. Permanent Indus Commission meet begins in Delhi The Indian delegation for the annual meeting comprises India’s Indus Water Commissioner P K Saxena, a representative of the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) and technical experts, sources said. • Pakistan’s six-member delegation for the commission’s 114th meeting is being led by Syed Muhammad Mehar Ali Shah. • The IWT covers the water distribution and sharing rights of six rivers — Beas, Ravi, Sutlej, Indus, Chenab and Jhelum. • The treaty specifies that waters from the three western rivers — Indus, Jhelum and Chenab — are reserved for Pakistan, while waters from eastern rivers — Ravi, Sutlej and Beas — are for reserved for India. 2. NASA to send first mission to study 'heart' of Mars Scheduled to launch on May 5, InSight - a stationary lander - will also be the first NASA mission since the Apollo moon landings to place a seismometer, a device that measures quakes, on the soil of another planet. • “In some ways, InSight is like a scientific time machine that will bring back information about the earliest stages of Mars' formation 4.5 billion years ago,” said Bruce Banerdt, principal investigator for InSight. • InSight or the Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport mission, carries a suite of sensitive instruments to gather data. Unlike a rover mission, these instruments require a stationary lander from which they can carefully be placed on and below the martian surface, NASA said. 3. E-Way Bill for Inter-State movement of goods comes into force With the beginning of the financial year 2018-19, the e-way Bill System for Inter-State movement of goods comes into force; An E-way Bill will be required for moving goods worth over 50,000 rupees from one state to another. -

Swiatek Ousts Top Seed Halep; Nadal Bests Korda

Sports Monday, October 5, 2020 15 Teen shock: Swiatek Indian Premier League ousts top seed Halep; Nadal bests Korda DPA LONDON Shane Watson (left) and Faf du Plessis shared an unbroken 181-run WOMEN’S top seed Simo- stand for the first wicket - the highest ever for the Chennai Super na Halep crashed out of the Kings in the IPL in Dubai on Sunday. French Open fourth round on Sunday after the world num- ber two was stunned 6-1, 6-2 Watson, Du Plessis fire in 68 minutes by Polish teen- ager Iga Swiatek. as CSK humble KXIP Fifth seed Kiki Bertens of the Netherlands is also out AFP “I am known for swing after losing 6-4, 6-4 to Italy’s DUBAI and not for slower ones with Martina Trevisan, who will the new ball, but you just use share a first-ever Grand Slam NEW Zealand quick Trent variations and angles.” quarter-final with Swiatek. Boult returned figures of Boult got the key wickets “I felt like I was playing 2-28 as he overcame hot of England batsman Jonny perfectly,” Swiatek said in an Spain’s Rafael Nadal celebrates after winning against Sebastian UAE weather to help holders Bairstow for 25 and his na- interview on Court Philippe Korda of the US on Sunday. (AFP) Mumbai Indians reach top of tional captain Kane William- Chatrier. “I was so focused the Indian Premier League son, caught behind for three, the whole match and I’m sur- table on Sunday. to choke David Warner’s Hy- prised I could do that. -

9. DC GK October

DESIZN CIRCLE www.desizncircle.com D.C. G.K. (October) 1. Who has been unanimously elected Chairman of the Press Trust of India? - N. Ravi 2. Who was elected Vice-Chairman of PTI? - Vijay Kumar Chopra 3. The theme of Int'l Translation Day 2018 (Sep30) is? - Translation: Promoting Cultural Heritage in Changing Times 4. When did India's population touch 100 crore mark? A) May, 2001 B) May 2000 C) May, 2002 D) May, 2003 Ans: B. (May 2000) 5. What type of fighter jets will India gifting to Russia? - MiG-21 6. Who won Asian Jr. Squash title? - Yuvraj Wadhwani 7. Which company combines with Indian Railways for Rail Heritage Digitization Project’? - Google 8. Who won Russian GP? – Lewis Hamilton 9. The Nobel Prizes giving to honour of? – Alfred Nobel 10. The Nobel Prize first awarded in? - 1901 11. Who jointly awarded 2018 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation? -- James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo 12. India’s first comprehensive city-level Flood Forecasting & Warning System gets? - Kolkata 13. The theme for 2018 Int'l Day of Older Persons? - “Celebrating Older Human Rights champions” 14. Which is 1st state to launch wage compensation scheme for pregnant women in tea gardens? – Assam 15. At which place Gandhi ji born? - Porbandar 16. What was Gandhi ji's age when he got married to Kasturbai? - 13 years 17. At which place was Gandhi ji arrested for 1st time by British Govt. for sedition? - Ahmadabad 18. What was Gandhi ji's nickname in childhood? - Manu / Moniya 19. -

The Late Dr H. B. Singh

T he Late Dr H. B. Singh (L916-1974) WILD EDIBLE PLANTS OF INDIA H. B. SINGH AND R. K. ARORA National Bureau of Plant Genetie Resources 1. A. R. 1. Campus, New Delhi . !CAB INDIAN COUNCIL OF AGRIOULTURAL RESEAROH NEW DELHI FIRST PRINTED, MARCH 1978 Chiif Editor : P. L. JAISWAL Editor,' K. B. NAIR Asstt. Editor,' I. J. LALL Clti~f Production o'{jiccr " KRlSHAN KUMAR ProdllctiDn Assistant : J. L. CULlAN! Price : Rs 8.20 A'~S\\~ ~i fa, ii, It, l.H'i.~.4.1l.~. IJ.lWDJlLBl. Printed in Indi;; by n .. D. Sen .at the N,,\J;I :h1u(lr;1.n (P) Ltd., 170~! Acharya .Prafulla Chandxa Road, Calcutta and publi,hed by P.j.:Toseph, Uncler Secretary for the Indian Council of Agricultural Rcse,!rch, New Delhi. Dr HARBHAJAN SINGH (19l6-l974) DR Harbhajan Singh was born at Pusa (Bihar) on February 6, 1916. After obtaining the degree of Master of Science in Botany fi'om Agra Uni versity in 1938, he joined the Indian (then Imperial) Agricultural Research Institute for a t-wo-year Diploma course of Associateship in Economic Botany. Thereafter, he was taken up on the research staff of the Division of Botany where h.e pursued his scientific career with imlllcnse zeal and devotion, and rose to the position of the Head of the Division of Plant Introduction in that Institute. Dr Singh was among the first to l'calisc the immense possibilities of crop improvcment in India through systematic plant introduction and exploration. He was a plant explorer of eminence with regard to cultivated plants and their wild relatives, and carried out one-man trips, as well as led teams of agricultural plant explorers to different parts of India and the neighbouring countries such as Nepal. -

Sadhana Academy Ph:9290699996

SADHANA ACADEMY PH:9290699996 INDIAN AFFAIRS Cabinet Approvals on November 11, 2017 On November 10, 2017, Union Cabinet chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi approved following initiatives and bilateral agreements. i. Cabinet approves MoU between India and Philippines on agriculture and related fields ii. Cabinet has approved agreement between India and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) of China for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with respect to taxes on income. iii. Cabinet approves amending DTAA with Kyrgyzstan iv. Cabinet approves Joint Interpretative Declaration between India and Colombia v. Cabinet approves continuation and Restructuring of National Rural Drinking Water Programme Government to adopt land-pooling method for airport expansion Airports Authority of India (AAI) Chairman, Guruprasad Mohapatra has stated that, Central Government is working on adopting the ‘Land Pooling’ methodology as an alternative mechanism for development and expansion of airports. i. Indian aviation space has witnessed a significant surge in air passenger traffic in recent years. In order to accommodate this growth, AAI has already chalked out plans to expand current capacities of terminals and bays at airports. However the increased capacity too will be saturated on account of high growth and more land will be needed for further expansion. ii. In this situation, ‘Land Pooling’ emerges as the only available and viable alternative for airports expansion Union Cabinet approves Creation of National Testing Agency (NTA) On November 10, 2017, Union Cabinet chaired by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, cleared a proposal for creation of a National Testing Agency (NTA) which will conduct various entrance examinations. -

Reliance Icc T20i Championship (Before the Australia-Pakistan, England-South Africa and India-New Zealand Series)

RELIANCE ICC T20I CHAMPIONSHIP (BEFORE THE AUSTRALIA-PAKISTAN, ENGLAND-SOUTH AFRICA AND INDIA-NEW ZEALAND SERIES) Rank Team Rating 1 England 130 2 South Africa 129 3 Sri Lanka 119 4 West Indies 111 5 New Zealand 109 6 Pakistan 108 7 India 101 8 Bangladesh 95 9 Australia 94 10 Ireland 88 11 Zimbabwe 47 NOT RANKED AS FEWER THAN EIGHT T20I MATCHES PLAYED SINCE AUGUST 2010 Afghanistan 92 Netherlands 73 Scotland 67 Canada 11 Kenya 2 (Developed by David Kendix) RELIANCE ICC T20 RANKINGS (AS ON 13 SEPTEMBER, AFTER ENGLAND-SOUTH AFRICA, INDIA-NEW ZEALAND AND PAKISTAN-AUSTRALIA SERIES) BATSMEN Rank (+/-) Player Team Pts Ave S/R HS Ranking 1 (+2) B McCullum NZ 793 36.07 132 833 v Aus at Christchurch 2010 2 (+3) Chris Gayle WI 744 36.04 144 826 v Ind at Barbados 2010 3 (+1) Suresh Raina Ind 742 32.90 138 776 v Eng at Kolkata 2011 4 (+6) David Warner Aus 738 27.16 141 826 v WI at St Lucia 2010 5 (-3) Martin Guptill NZ 737 32.72 125 793 v SA at Hamilton 2012 6 ( - ) M Jayawardena SL 732 30.65 139 785 v Aus at Pallekele 2011 7 ( - ) Shane Watson Aus 731 27.07 148 732 v WI at St Lucia 2012 8 (+4) Jacques Kallis SA 722 40.12 122 738 v Eng at Durham 2012 9 (-8) Eoin Morgan Eng 710 36.35 133 872 v Ind at Old Trafford 2011 10 (-2) T Dilshan SL 695 29.58 124 802 v NZ at Colombo (RPS) 2009 11 (-2) K Sangakkara SL 686 30.33 120 763 v WI at Barbados 2010 12 (-1) JP Duminy SA 663 32.53 123 694 v Eng at Durham 2012 13 (+1) H Masakadza Zim 649*! 27.95 121 649 v NZ at Hamilton 2012 14 (-1) Graeme Smith SA 630 31.67 128 778 v Zim at Kimberley 2010 15 (RE) Yuvraj -

Cobbling Together the Dream Indian Eleven

COBBLING TOGETHER THE DREAM INDIAN ELEVEN Whenever the five selectors, often dubbed as the five wise men with the onerous responsibility of cobbling together the best players comprising India’s test cricket team, sit together to pick the team they feel the heat of the country’s collective gaze resting on them. Choosing India’s cricket team is one of the most difficult tasks as the final squad is subjected to intense scrutiny by anybody and everybody. Generally the point veers round to questions such as why batsman A was not picked or bowler B was dropped from the team. That also makes it a very pleasurable hobby for followers of the game who have their own views as to who should make the final 15 or 16 when the team is preparing to leave our shores on an away visit or gearing up to face an opposition on a tour of our country. Arm chair critics apart, sports writers find it an enjoyable professional duty when they sit down to select their own team as newspapers speculate on the composition of the squad pointing out why somebody should be in the team at the expense of another. The reports generally appear on the sports pages on the morning of the team selection. This has been a hobby with this writer for over four decades now and once the team is announced, you are either vindicated or amused. And when the player, who was not in your frame goes on to play a stellar role for the country, you inwardly congratulate the selectors for their foresight and knowledge. -

Match Report

Match Report Mumbai Indians, Mumbai Indians vs Royal Challengers Bangalore, Royal Challengers Bangalore Mumbai Indians, Mumbai Indians Won Date: Tue 06 May 2014 Location: India - Maharashtra Match Type: Twenty20 Scorer: Sreenath Puthiyedath Toss: Royal Challengers Bangalore, Royal Challengers Bangalore won the toss and elected to Bowl URL: http://www.crichq.com/matches/136442 Mumbai Indians, Mumbai Royal Challengers Bangalore, Indians Royal Challengers Bangalore Score 187-5 Score 168-8 Overs 20.0 Overs 20.0 BR Dunk CH Gayle CM Gautam PA Patel AT Rayudu V Kohli* RG Sharma* R Rossouw CJ Anderson AB de Villiers KA Pollard Y Singh AP Tare MA Starc H Singh HV Patel PS Suyal AB Dinda JJ Bumrah VR Aaron SL Malinga YS Chahal page 1 of 34 Scorecards 1st Innings | Batting: Mumbai Indians, Mumbai Indians R B 4's 6's SR BR Dunk . 1 2 . 4 1 4 2 . 1 . // c Y Singh b HV Patel 15 14 2 0 107.14 CM Gautam . 4 1 1 . 6 . 6 . 4 . 1 . 6 . 1 . // c PA Patel b VR Aaron 30 28 2 3 107.14 AT Rayudu 1 1 . 1 1 4 1 . // b AB Dinda 9 9 1 0 100.0 RG Sharma* . 1 1 1 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 . 1 1 4 . 1 6 1 6 4 6 2 6 . 1 2 4 not out 59 35 3 4 168.57 CJ Anderson . 6 . // c V Kohli* b YS Chahal 6 4 0 1 150.0 KA Pollard . 1 4 1 . 1 1 4 .