Monitoring of a Population of Galápagos Land Iguanas (Conolophus Subcristatus) During a Rat Eradication Using Brodifacoum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chuckwalla Habitat in Nevada

Final Report 7 March 2003 Submitted to: Division of Wildlife, Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, State of Nevada STATUS OF DISTRIBUTION, POPULATIONS, AND HABITAT RELATIONSHIPS OF THE COMMON CHUCKWALLA, Sauromalus obesus, IN NEVADA Principal Investigator, Edmund D. Brodie, Jr., Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2485 Co-Principal Investigator, Thomas C. Edwards, Jr., Utah Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit and Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5210 (435)797-2509 Research Associate, Paul C. Ustach, Department of Biology, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5305 (435)797-2450 1 INTRODUCTION As a primary consumer of vegetation in the desert, the common chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus (=ater; Hollingsworth, 1998), is capable of attaining high population density and biomass (Fitch et al., 1982). The 21 November 1991 Federal Register (Vol. 56, No. 225, pages 58804-58835) listed the status of chuckwalla populations in Nevada as a Category 2 candidate for protection. Large size, open habitat and tendency to perch in conspicuous places have rendered chuckwallas particularly vulnerable to commercial and non-commercial collecting (Fitch et al., 1982). Past field and laboratory studies of the common chuckwalla have revealed an animal with a life history shaped by the fluctuating but predictable desert climate (Johnson, 1965; Nagy, 1973; Berry, 1974; Case, 1976; Prieto and Ryan, 1978; Smits, 1985a; Abts, 1987; Tracy, 1999; and Kwiatkowski and Sullivan, 2002a, b). Life history traits such as annual reproductive frequency, adult survivorships, and population density have all varied, particular to the population of chuckwallas studied. Past studies are mostly from populations well within the interior of chuckwalla range in the Sonoran Desert. -

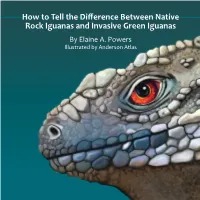

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Volcanoes & Land Iguanas

Volcanoes & Land Iguanas 1/2 Background Galapagos iguanas are thought to of arrived in the Galapagos archipelago by floating on of rafts of vegetation from the South American continent. It is estimated that a split of iguana species into Land and Marine Iguanas occurred around 10.5 million years ago. In Galapagos, 3 species of land Iguanas now exist. The Land Iguanas include: Conolophus subcristatus (found on 6 islands), Conolophus pallidus (found only on Santa Fe Island) and a third species Conolophus rosada (known for its pink colour) is found on Wolf volcano on Isabela Island. Habitat Land Iguanas are found in the drier areas of the island. Being cold- blooded, to keep warm they bask in the sun and on the volcanic rock, escaping the midday sun by finding shade under vegetation and rocks, and sleeping in burrows to conserve their body heat. Land Iguanas feed on vegetation such as fallen fruits and cactus pads and even the spines of prickly pear © David cactus. Phillips © Galapagos Conservation © Cyder Trust Volcanoes & Land Iguanas 2/2 Reproduction Between 6 and 10 years of age, male Land Iguanas become highly aggressive, fighting for the attention of the female Land Iguanas. Mating then takes place at the end of the year and eggs are usually laid between January and March (June on Fernandina!). However, in order to lay these eggs female Land Iguanas have no option but to scale to the summit of volcanoes. © Phil Herbert The Volcanic Importance Every pregnant female will need to find a patch of volcanic ash; these pockets of warm soft soil are perfect for the incubation of their eggs; however these sites are difficult to come by. -

Roatán Spiny-Tailed Iguana (Ctenosaura Oedirhina) Conservation Action Plan 2020–2025 Edited by Stesha A

Roatán spiny-tailed iguana (Ctenosaura oedirhina) Conservation action plan 2020–2025 Edited by Stesha A. Pasachnik, Ashley B.C. Goode and Tandora D. Grant INTERNATIONAL UNION FOR CONSERVATION OF NATURE IUCN IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, helps the world find pragmatic solutions to our most pressing environment and development challenges. IUCN works on biodiversity, climate change, energy, human livelihoods and greening the world economy by supporting scientific research, managing field projects all over the world, and bringing governments, NGOs, the UN and companies together to develop policy, laws and best practice. IUCN is the world’s oldest and largest global environmental organization, with more than 1,400 government and NGO members and almost 15,000 volunteer experts in some 160 countries. IUCN’s work is supported by around 950 staff in more than 50 countries and hundreds of partners in public, NGO and private sectors around the world. www.iucn.org IUCN Species Programme The IUCN Species Programme supports the activities of the IUCN Species Survival Commission and individual Specialist Groups, as well as implementing global species conservation initiatives. It is an integral part of the IUCN Secretariat and is managed from IUCN’s international headquarters in Gland, Switzerland. The Species Programme includes a number of technical units covering Wildlife Trade, the Red List, Freshwater Biodiversity Assessments (all located in Cambridge, UK), and the Global Biodiversity Assessment Initiative (located in Washington DC, USA). IUCN Species Survival Commission The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions with a global membership of more than 9,000 experts. -

Iguanas in Florida N Green and Spinytail Iguanas Are Native to Central and South America, but Are Commonly Found in the Exotic Pet Trade

Iguana fast facts n Iguanas are large lizards that can grow over 4 feet in length. Iguanas in Florida n Green and spinytail iguanas are native to Central and South America, but are commonly found in the exotic pet trade. n Iguanas bask in open areas and are often seen on sidewalks, docks, patios, decks, in trees or open mowed areas. n They can run or climb swiftly when frightened and dive into water or retreat into burrows or thick foliage. n Green iguanas can range from green to Black spinytail iguana, Adam G. Stern grayish black in color and have a row of spikes down the center of the head and back. n During the breeding season, adult male green iguanas can sometimes take on an orange hue. n Spinytail iguanas can range from gray to dark tan in color with black bands and have whorls of spiny scales on the tail. n Green iguanas are mainly herbivores and feed primarily on leaves, flowers and fruits of Mexican spinytail iguana, Kenneth L. Krysko various broad-leaved herbs, shrubs and trees, but will feed on other items opportunistically. If you have further questions or need more n Spinytail iguanas are omnivorous, eating help, call your regional Florida Fish and primarily vegetation, but have been Wildlife Conservation Commission office: documented eating small animals and eggs. Three members of the iguana family are now established in South Florida and occasionally observed in other parts of Florida: the green Main Headquarters iguana, the Mexican spinytail iguana, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission black spinytail iguana. -

RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura Cornuta Cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789)

HUSBANDRY GUIDELINES: RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura cornuta cornuta (Bonnaterre 1789) REPTILIA: IGUANIDAE Compiler: Cameron Candy Date of Preparation: DECEMBER, 2009 Institute: Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond, NSW, Australia Course Name/Number: Certificate III in Captive Animals - 1068 Lecturers: Graeme Phipps - Jackie Salkeld - Brad Walker Husbandry Guidelines: C. c. cornuta 1 ©2009 Cameron Candy OHS WARNING RHINOCEROS IGUANA Cyclura c. cornuta RISK CLASSIFICATION: INNOCUOUS NOTE: Adult C. c. cornuta can be reclassified as a relatively HAZARDOUS species on an individual basis. This may include breeding or territorial animals. POTENTIAL PHYSICAL HAZARDS: Bites, scratches, tail-whips: Rhinoceros Iguanas will defend themselves when threatened using bites, scratches and whipping with the tail. Generally innocuous, however, bites from adults can be severe resulting in deep lacerations. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of injury from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - Keep animal away from face and eyes at all times - Use of correct PPE such as thick gloves and employing correct and safe handling techniques when close contact is required. Conditioning animals to handling is also generally beneficial. - Collection Management; If breeding is not desired institutions can house all female or all male groups to reduce aggression - If aggressive animals are maintained protective instrument such as a broom can be used to deflect an attack OTHER HAZARDS: Zoonosis: Rhinoceros Iguanas can potentially carry the bacteria Salmonella on the surface of the skin. It can be passed to humans through contact with infected faeces or from scratches. Infection is most likely to occur when cleaning the enclosure. RISK MANAGEMENT: To reduce the risk of infection from these lizards the following steps should be followed: - ALWAYS wash hands with an antiseptic solution and maintain the highest standards of hygiene - It is also advisable that Tetanus vaccination is up to date in the event of a severe bite or scratch Husbandry Guidelines: C. -

TERRESTRIAL SPECIES Grand Cayman Blue Iguana Cyclura Lewisi Taxonomy and Range the Grand Cayman Blue Iguana, Cyclura Lewisi, Is

TERRESTRIAL SPECIES Grand Cayman Blue iguana Cyclura lewisi Taxonomy and Range Kingdom: Animalia, Phylum: Chordata, Class: Sauropsida, Order: Squamata, Family: Iguanidae Genus: Cyclura, Species: lewisi The Grand Cayman Blue iguana, Cyclura lewisi, is endemic to the island of Grand Cayman. Closest relatives are Cyclura nubila (Cuba), and Cyclura cychlura (Bahamas); all three having apparently diverged from a common ancestor some three million years ago. Status Distribution: Species endemic to Grand Cayman. Conservation: Critically endangered (IUCN Red List). In 2002 surveys indicated a wild population of 10-25 individuals. By 2005 any young being born into the unmanaged wild population were not surviving to breeding age, making the population functionally extinct. Cyclura lewisi is now the most endangered iguana on Earth. Legal: The Grand Cayman Blue iguana Cyclura lewisi is protected under the Animals Law (1976). Pending legislation, it would be protected under the National Conservation Law (Schedule I). The Department of Environment is the lead body for legal protection. The Blue Iguana Recovery Programme BIRP operates under an exemption to the Animals Law, granted to the National Trust for the Cayman Islands. Natural history While it is likely that the original population included many animals living in coastal shrubland environments, the Blue iguana now only occurs inland, in natural dry shrubland, and along the margins of dry forest. Adults are primarily terrestrial, occupying rock holes and low tree cavities. Younger individuals tend to be more arboreal. Like all Cyclura species the Blue iguana is primarily herbivorous, consuming leaves, flowers and fruits. This diet is very rarely supplemented with insect larvae, crabs, slugs, dead birds and fungi. -

An Overlooked Pink Species of Land Iguana in the Galápagos Gabriele Gentilea,1, Anna Fabiania, Cruz Marquezb, Howard L

An overlooked pink species of land iguana in the Galápagos Gabriele Gentilea,1, Anna Fabiania, Cruz Marquezb, Howard L. Snellc, Heidi M. Snellc, Washington Tapiad, and Valerio Sbordonia aDipartimento di Biologia, Universita` Tor Vergata, 00133 Rome, Italy; bCharles Darwin Foundation, Puerto Ayora, Gala´ pagos Islands, Ecuador; cDepartment of Biology and Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131; and dGalápagos National Park Service, Puerto Ayora, Gala´ pagos Islands, Ecuador Edited by Francisco J. Ayala, University of California, Irvine, CA, and approved November 11, 2008 (received for review July 2, 2008) Despite the attention given to them, the Galápagos have not yet finished offering evolutionary novelties. When Darwin visited the Galápagos, he observed both marine (Amblyrhynchus) and land (Conolophus) iguanas but did not encounter a rare pink black- striped land iguana (herein referred to as ‘‘rosada,’’ meaning ‘‘pink’’ in Spanish), which, surprisingly, remained unseen until 1986. Here, we show that substantial genetic isolation exists between the rosada and syntopic yellow forms and that the rosada is basal to extant taxonomically recognized Galápagos land igua- nas. The rosada, whose present distribution is a conundrum, is a relict lineage whose origin dates back to a period when at least some of the present-day islands had not yet formed. So far, this species is the only evidence of ancient diversification along the Galápagos land iguana lineage and documents one of the oldest events of divergence ever recorded in the Galápagos. Conservation efforts are needed to prevent this form, identified by us as a good species, from extinction. Fig. 1. Galápagos Islands. -

1 Connor Pierson Dr. William Durham Darwin, Evolution, and Galapagos

Connor Pierson Dr. William Durham Darwin, Evolution, and Galapagos 10/12/09 The Evolutionary Significance of the Pink Iguana Introduction: In 1986, Galapagos park rangers patrolling the remote summit of Volcán Wolf reported a sighting of a Galapagos land iguana with an unusual characteristic: bright pink scales. While many dismissed the anomaly as a skin condition, Dr. Gabriele Gentile from the Tor Vergata University of Rome and his team began searching for the elusive pink iguana in 2005. The next year the team (which included Howard and Heidi Snell) successfully captured, measured, and drew samples from 32 iguanas displaying the unique phenotype. The population was nicknamed, “Rosada,” the Spanish word for pink. The public was introduced to the iguana with the publication of a genetic analysis on January 13, 2009. The results published in this paper suggested that Rosada deserved recognition as a unique species due to its morphological, behavioral, and genetic differences from the two already recognized members of the genus Conolophus. On August 18, 2009 an official description of a new species, Conolophus marthae, was published in the taxonomical journal Zootaxa. While several research papers are pending, the information currently available challenges accepted theory regarding the evolution of the iguana in the Galapagos. The goals of this paper are to: (a.) introduce the reader to a distinctive new species of Galapagos Megafauna; (b.) analyze marthae’s significance in terms of current understanding of Galapagos Iguana evolution; (c.) suggest the probable route of colonization for the new species; and (d.) highlight the need for conservation and further research.1 1 Meet Rosada: Description: Conolophus marthae’s striking coloration, nuchal crest, and communicative signals distinguish the iguana from its genetic relatives, subcristatus, and pallidus. -

Sex-Specific Behavioral Strategies for Thermoregulation in the Comon Chuckwalla (Sauromalus Ater) ______

SEX-SPECIFIC BEHAVIORAL STRATEGIES FOR THERMOREGULATION IN THE COMON CHUCKWALLA (SAUROMALUS ATER) ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Biology ____________________________________ By Emily Rose Sanchez Thesis Committee Approval: Christopher R. Tracy, Department of Biological Science, Chair Sean E. Walker, Department of Biological Science Paul Stapp, Department of Biological Science Spring, 2018 ABSTRACT Intraspecific variability of behavioral thermoregulation in lizards due to habitat, temperature availability, and seasonality is well documented, but variability due to sex is not. Sex-specific thermoregulatory behaviors are important to understand because they can affect relative fitness in ways that result in different responses to environmental changes. The common chuckwalla (Sauromalus ater) is a great model for investigating sex differences in thermoregulation because males behave differently from females while they actively defend distinct territories while females may not. I recorded body temperatures of wild adult chuckwallas continuously from May to July 2016, as well as operative environmental temperatures in crevices and aboveground sites used by chuckwallas for basking. I compared the effect of sex on indices of thermoregulatory accuracy and effectiveness, aboveground activity, and the time chuckwallas selected body temperatures relative -

Evolution of the Iguanine Lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) As Determined by Osteological and Myological Characters

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1970-08-01 Evolution of the iguanine lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) as determined by osteological and myological characters David F. Avery Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Life Sciences Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Avery, David F., "Evolution of the iguanine lizards (Sauria, Iguanidae) as determined by osteological and myological characters" (1970). Theses and Dissertations. 7618. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/7618 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. EVOLUTIONOF THE IGUA.NINELI'ZiUIDS (SAUR:U1., IGUANIDAE) .s.S DETEH.MTNEDBY OSTEOLOGICJJJAND MYOLOGIC.ALCHARA.C'l'Efi..S A Dissertation Presented to the Department of Zoology Brigham Yeung Uni ver·si ty Jn Pa.rtial Fillf.LLlment of the Eequ:Lr-ements fer the Dz~gree Doctor of Philosophy by David F. Avery August 197U This dissertation, by David F. Avery, is accepted in its present form by the Department of Zoology of Brigham Young University as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 30 l'/_70 ()k ate Typed by Kathleen R. Steed A CKNOWLEDGEHENTS I wish to extend my deepest gratitude to the members of m:r advisory committee, Dr. Wilmer W. Tanner> Dr. Harold J. Bissell, I)r. Glen Moore, and Dr. Joseph R. Murphy, for the, advice and guidance they gave during the course cf this study. -

Molecular Systematics & Evolution of the CTENOSAURA HEMILOPHA

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 9-1999 Molecular Systematics & Evolution of the CTENOSAURA HEMILOPHA Complex (SQUAMATA: IGUANIDAE) Michael Ray Cryder Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Cryder, Michael Ray, "Molecular Systematics & Evolution of the CTENOSAURA HEMILOPHA Complex (SQUAMATA: IGUANIDAE)" (1999). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 613. https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/613 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOMA LINDAUNIVERSITY Graduate School MOLECULARSYSTEMATICS & EVOLUTION OF THECTENOSAURA HEMJLOPHA COMPLEX (SQUAMATA: IGUANIDAE) by Michael Ray Cryder A Thesis in PartialFulfillment of the Requirements forthe Degree Master of Science in Biology September 1999 0 1999 Michael Ray Cryder All Rights Reserved 11 Each person whose signature appears below certifies that this thesis in their opinion is adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree Master of Science. ,Co-Chairperson Ronald L. Carter, Professor of Biology Arc 5 ,Co-Chairperson L. Lee Grismer, Professor of Biology and Herpetology - -/(71— William Hayes, Pr fessor of Biology 111 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to the institution and individuals who helped me complete this study. I am grateful to the Department of Natural Sciences, Lorna Linda University, for scholarship, funding and assistantship.