Queer Womenâ•Žs Use of Temporary Urban

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Montréal's Gay Village

Produced By: Montréal’s Gay Village Welcoming and Increasing LGBT Visitors March, 2016 Welcoming LGBT Travelers 2016 ÉTUDE SUR LE VILLAGE GAI DE MONTRÉAL Partenariat entre la SDC du Village, la Ville de Montréal et le gouvernement du Québec › La Société de développement commercial du Village et ses fiers partenaires financiers, que sont la Ville de Montréal et le gouvernement du Québec, sont heureux de présenter cette étude réalisée par la firme Community Marketing & Insights. › Ce rapport présente les résultats d’un sondage réalisé auprès de la communauté LGBT du nord‐est des États‐ Unis (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, État de New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvanie, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginie, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois), du Canada (Ontario et Colombie‐Britannique) et de l’Europe francophone (France, Belgique, Suisse). Il dresse un portrait des intérêts des touristes LGBT et de leurs appréciations et perceptions du Village gai de Montréal. › La première section fait ressortir certaines constatations clés alors que la suite présente les données recueillies et offre une analyse plus en détail. Entre autres, l’appréciation des touristes qui ont visité Montréal et la perception de ceux qui n’en n’ont pas eu l’occasion. › L’objectif de ce sondage est de mieux outiller la SDC du Village dans ses démarches de promotion auprès des touristes LGBT. 2 Welcoming LGBT Travelers 2016 ABOUT CMI OVER 20 YEARS OF LGBT INSIGHTS › Community Marketing & Insights (CMI) has been conducting LGBT consumer research for over 20 years. Our practice includes online surveys, in‐depth interviews, intercepts, focus groups (on‐site and online), and advisory boards in North America and Europe. -

Cultivating the Daughters of Bilitis Lesbian Identity, 1955-1975

“WHAT A GORGEOUS DYKE!”: CULTIVATING THE DAUGHTERS OF BILITIS LESBIAN IDENTITY, 1955-1975 By Mary S. DePeder A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History Middle Tennessee State University December 2018 Thesis Committee: Dr. Susan Myers-Shirk, Chair Dr. Kelly A. Kolar ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I began my master’s program rigidly opposed to writing a thesis. Who in their right mind would put themselves through such insanity, I often wondered when speaking with fellow graduate students pursuing such a goal. I realize now, that to commit to such a task, is to succumb to a wild obsession. After completing the paper assignment for my Historical Research and Writing class, I was in far too deep to ever turn back. In this section, I would like to extend my deepest thanks to the following individuals who followed me through this obsession and made sure I came out on the other side. First, I need to thank fellow history graduate student, Ricky Pugh, for his remarkable sleuthing skills in tracking down invaluable issues of The Ladder and Sisters. His assistance saved this project in more ways than I can list. Thank-you to my second reader, Dr. Kelly Kolar, whose sharp humor and unyielding encouragement assisted me not only through this thesis process, but throughout my entire graduate school experience. To Dr. Susan Myers- Shirk, who painstakingly wielded this project from its earliest stage as a paper for her Historical Research and Writing class to the final product it is now, I am eternally grateful. -

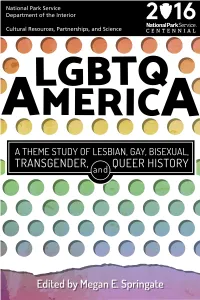

LGBTQ America: a Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PLACES Unlike the Themes section of the theme study, this Places section looks at LGBTQ history and heritage at specific locations across the United States. While a broad LGBTQ American history is presented in the Introduction section, these chapters document the regional, and often quite different, histories across the country. In addition to New York City and San Francisco, often considered the epicenters of LGBTQ experience, the queer histories of Chicago, Miami, and Reno are also presented. QUEEREST28 LITTLE CITY IN THE WORLD: LGBTQ RENO John Jeffrey Auer IV Introduction Researchers of LGBTQ history in the United States have focused predominantly on major cities such as San Francisco and New York City. This focus has led researchers to overlook a rich tradition of LGBTQ communities and individuals in small to mid-sized American cities that date from at least the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century. -

It's a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses Spring 2011 It’s a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood Cori E. Walter Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Urban Studies Commons Recommended Citation Walter, Cori E., "It’s a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood" (2011). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 6. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/6 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. It’s a Beautiful Day in the Gayborhood A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Cori E. Walter May, 2011 Mentor: Dr. Claire Strom Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida 2 Table of Contents________________________________________________________ Introduction Part One: The History of the Gayborhood The Gay Ghetto, 1890 – 1900s The Gay Village, 1910s – 1930s Gay Community and Districts Go Underground, 1940s – 1950s The Gay Neighborhood, 1960s – 1980s Conclusion Part Two: A Short History of the City Urban Revitalization and Gentrification Part Three: Orlando’s Gay History Introduction to Thornton Park, The New Gayborhood Thornton Park, Pre-Revitalization Thornton Park, The Transition The Effects of Revitalization Conclusion 3 Introduction_____________________________________________________________ Mister Rogers' Neighborhood is the longest running children's program on PBS. -

Barbara Grier--Naiad Press Collection

BARBARA GRIER—NAIAD PRESS COLLECTION 1956-1999 Collection number: GLC 30 The James C. Hormel Gay and Lesbian Center San Francisco Public Library 2003 Barbara Grier—Naiad Press Collection GLC 30 p. 2 Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction p. 3-4 Biography and Corporate History p. 5-6 Scope and Content p. 6 Series Descriptions p. 7-10 Container Listing p. 11-64 Series 1: Naiad Press Correspondence, 1971-1994 p. 11-19 Series 2: Naiad Press Author Files, 1972-1999 p. 20-30 Series 3: Naiad Press Publications, 1975-1994 p. 31-32 Series 4: Naiad Press Subject Files, 1973-1994 p. 33-34 Series 5: Grier Correspondence, 1956-1992 p. 35-39 Series 6: Grier Manuscripts, 1958-1989 p. 40 Series 7: Grier Subject Files, 1965-1990 p. 41-42 Series 8: Works by Others, 1930s-1990s p. 43-46 a. Printed Works by Others, 1930s-1990s p. 43 b. Manuscripts by Others, 1960-1991 p. 43-46 Series 9: Audio-Visual Material, 1983-1990 p. 47-53 Series 10: Memorabilia p. 54-64 Barbara Grier—Naiad Press Collection GLC 30 p. 3 Gay and Lesbian Center, San Francisco Public Library INTRODUCTION Provenance The Barbara Grier—Naiad Press Collection was donated to the San Francisco Public Library by the Library Foundation of San Francisco in June 1992. Funding Funding for the processing was provided by a grant from the Library Foundation of San Francisco. Access The collection is open for research and available in the San Francisco History Center on the 6th Floor of the Main Library. -

Enter Your Title Here in All Capital Letters

EXPLORING THE COMPOSITION AND FORMATION OF LESBIAN SOCIAL TIES by LAURA S. LOGAN B.A., University of Nebraska at Kearney, 2006 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2008 Approved by: Major Professor Dana M. Britton Copyright LAURA S. LOGAN 2008 Abstract The literature on friendship and social networks finds that individuals form social ties with people who are like them; this is termed “homophily.” Several researchers demonstrate that social networks and social ties are homophilous with regard to race and class, for example. However, few studies have explored the relationship of homophily to the social ties of lesbians, and fewer still have explicitly examined sexual orientation as a point of homophily. This study intends to help fill that gap by looking at homophily among lesbian social ties, as well as how urban and non-urban residency might shape homophily and lesbian social ties. I gathered data that would answer the following central research questions: Are lesbian social ties homophilous and if so around what common characteristics? What are lesbians’ experiences with community resources and how does this influence their social ties? How does population influence lesbian social ties? Data for this research come from 544 responses to an internet survey that asked lesbians about their social ties, their interests and activities and those of their friends, and the cities or towns in which they resided. Using the concepts of status and value homophily, I attempt to make visible some of the factors and forces that shape social ties for lesbians. -

Pride Parades, Public Space and Sexual Dissidence

Identities, Sexualities and Commemorations: Pride Parades, Public Space and Sexual Dissidence Identities, Sexualities and Commemorations: Pride Parades, Public Space and Sexual Dissidence Begonya Enguix Universitat Oberta de Catalunya, [email protected] ABSTRACT In this article, we will approach the mechanisms used for entitlement and the way in which public space has been reappropriated and resignified by sexual dissidents as a space for vindication, visibilization and commemoration. We will do so through the analysis of the LGTB Pride Parades in Spain – Madrid Pride in particular – and through an analysis of the relationship between territorialisation, communities (shared identities) and political activ- ism. The use of public space as a specific locus for entitlement and commemoration has only been possible in Spain since democracy was restored and, therefore, it is politically meaningful. LGTB Pride Parades marching through central streets do not only occupy, but ‘produce’ space and identities. They constitute a privileged field for the analysis of the mechanisms through which sexual diversity manifests and expresses social and subjec- tive identities which are intertwined with discourses and counter-discourses that can be traced through the participation (or absence) from the event, through the strategies of re- presentation displayed and through the narratives about this event. This work is based on systematic observation of the 2006, 2007 and 2008 Madrid parades and on the observa- tion of 2007 and 2008 Barcelona parades. We have also undertaken in-depth interviews with members of the organisation of Madrid Pride and Barcelona Pride 2009. It is preceded by intensive fieldwork on the gay community carried out intermittently from 1990 to the present day. -

The Invisible Lesbian: the Creation and Maintenance of Quiet Queer Space and the Social Power of Lesbian Bartenders

THE INVISIBLE LESBIAN: THE CREATION AND MAINTENANCE OF QUIET QUEER SPACE AND THE SOCIAL POWER OF LESBIAN BARTENDERS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Sociology Colorado College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts in Sociology By Kathleen Hallgren May/2012 ABSTRACT Despite extensive scholarship exploring relationships between space, gender, and sexuality, little attention has been given to lesbian/queer subjects in everyday heterosexual spaces such as bars. Furthermore, there is an absence of work addressing the bartender as a social actor. This research confronts those gaps by examining the social power of lesbian bartenders in straight bars to facilitate lesbian networks, and to cultivate and maintain “quiet queer spaces”—structurally heterosexual and socially heteronormative spaces that temporarily and covertly double as safe spaces for queer populations. By drawing on previous scholarship, and conducting a primary investigation through interviews and observations, I examine the creation and maintenance of quiet queer spaces in Colorado Springs bars to conclude that quiet queer spaces are both present and necessary in lesbian networks. I specifically examine the position of the lesbian bartender in straight bars as one of unique social power, essential in the creation and identification of quiet queer space. 2 After living in Colorado Springs for nearly four years, I could almost have been convinced that I was the only lesbian1 in the city. Beyond the campus of the city’s small liberal arts college, I saw no evidence of queer populations. This is curious, given recent studies2 that suggest one in every ten Americans is gay. -

Recovering the Gay Village: a Comparative Historical Geography of Urban Change and Planning in Toronto and Sydney

Chapter 11 Recovering the Gay Village: A Comparative Historical Geography of Urban Change and Planning in Toronto and Sydney Andrew Gorman-Murray and Catherine J. Nash Abstract This chapter argues that the historical geographies of Toronto’s Church and Wellesley Street district and Sydney’s Oxford Street gay villages are important in understanding ongoing contemporary transformations in both locations. LGBT and queer communities as well as mainstream interests argue that these gay villages are in some form of “decline” for various social, political, and economic reasons. Given their similar histories and geographies, our analysis considers how these histor- ical geographies have both enabled and constrained how the respective gay villages respond to these challenges, opening up and closing down particular possibilities for alternative (and relational) geographies. While there are a number of ways to consider these historical geographies, we focus on three factors for analysis: post- WorldWarIIplanningpolicies,theemergenceof“cityofneighborhoods”discourses, and the positioning of gay villages within neoliberal processes of commodification and consumerism. We conclude that these distinctive historical geographies offer a cogent set of understandings by providing suggestive explanations for how Toronto’s and Sydney’s gendered and sexual landscapes are being reorganized in distinctive ways, and offer some wider implications for urban planning and policy. Keywords Toronto, Canada Sydney, Austrlia Neighborhood Gayborhood Urban Change Urban Planning· · · · · 11.1 Introduction In this chapter, we examine the historical geographies of the now iconic gay villages in Toronto’s Church and Wellesley Street district and Sydney’s Oxford Street. We argue that a comparative historical geography approach provides insights into complex A. -

Bi,Butch,And Bar Dyke:Pedagogical Performances of Class,Gender,And Sexuality

SEP-CCC1.QXD 8/11/00 8:57 AM Page 69 Michelle Gibson, Martha Marinara, and Deborah Meem Bi,Butch,and Bar Dyke:Pedagogical Performances of Class,Gender,and Sexuality Current theories of radical pedagogy stress the constant undermining, on the part of both professors and students, of fixed essential identities. This article examines the way three feminist, queer teachers of writing experience and perform their gender, class, and sexual identities. We critique both the academy’s tendency to neutralize the political aspects of identity performance and the essentialist identity politics that still inform many academic discussions. Current theories of radical pedagogy stress the constant undermining, on the part of both professors and students, of fixed essential identities. Trinh Minh-Ha, for example, describes an “Inappropriate/d Other who moves about with always at least two/four gestures: that of affirming ‘I am like you’ while pointing insistently to the difference; and that of reminding ‘I am different’ while unsettling every definition of otherness arrived at” (8). Elizabeth Ells- worth applies Minh-Ha’s idea to “classroom practices that facilitate such mov- ing about” and the nature of identity that obtains in such classrooms: Identity in this sense becomes a vehicle for multiplying and making more com- plex the subject positions possible, visible, and legitimate at any given historical CCC 52:1 / SEPTEMBER 2000 69 SEP-CCC1.QXD 8/11/00 8:57 AM Page 70 CCC 52:1 / SEPTEMBER 2000 moment, requiring disruptive changes in the way social technologies of gender, race, ability, and so on define Otherness and use it as a vehicle for subordination. -

Queer Methods and Methodologies Queer Theories Intersecting and Social Science Research

Queer Methods and Queer Methods and Methodologies Methodologies provides the first systematic consideration of the implications of a queer perspective in the pursuit of social scientific research. This volume grapples with key contemporary questions regarding the methodological implications for social science research undertaken from diverse queer perspectives, and explores the limitations and potentials of queer engagements with social science research techniques and methodologies. With contributors based in the UK, USA, Canada, Sweden, New Zealand and Australia, this truly Queer Methods international volume will appeal to anyone pursuing research at the and Methodologies intersections between social scientific research and queer perspectives, as well as those engaging with methodological Intersecting considerations in social science research more broadly. Queer Theories This superb collection shows the value of thinking concretely about and Social Science queer methods. It demonstrates how queer studies can contribute to Research debates about research conventions as well as offer unconventional research. The book is characterised by a real commitment to queer as Edited by an intersectional study, showing how sex, gender and sexuality Kath Browne, intersect with class, race, ethnicity, national identity and age. Readers will get a real sense of what you can write in by not writing University of Brighton, UK out the messiness, difficulty and even strangeness of doing research. Catherine J. Nash, Sara Ahmed, Goldsmiths, University of London, UK Brock University, Canada Very little systematic thought has been devoted to exploring how queer ontologies and epistemologies translate into queer methods and methodologies that can be used to produce queer empirical research. This important volume fills that lacuna by providing a wide-ranging, comprehensive overview of contemporary debates and applications of queer methods and methodologies and will be essential reading for J. -

Making a Scene Lesbians and Community Across Canada, 1964-84

Liz Millward Making a Scene Lesbians and Community across Canada, 1964-84 Sample Material © 2015 UBC Press Sexuality Studies Series This series focuses on original, provocative, scholarly research examining from a range of perspectives the complexity of human sexual practice, identity, community, and desire. Books in the series explore how sexuality interacts with other aspects of society, such as law, education, feminism, racial diversity, the family, policing, sport, government, religion, mass media, medicine, and employment. The series provides a broad public venue for nurturing debate, cultivating talent, and expand- ing knowledge of human sexual expression, past and present. Other volumes in the series are: Masculinities without Men? Female Masculinity in Twentieth-Century Fictions, by Jean Bobby Noble Every Inch a Woman: Phallic Possession, Femininity, and the Text, by Carellin Brooks Queer Youth in the Province of the “Severely Normal,” by Gloria Filax The Manly Modern: Masculinity in Postwar Canada,by Christopher Dummitt Sexing the Teacher: School Sex Scandals and Queer Pedagogies, by Sheila L. Cavanagh Undercurrents: Queer Culture and Postcolonial Hong Kong, by Helen Hok-Sze Leung Sapphistries: A Global History of Love between Women, by Leila J. Rupp The Canadian War on Queers: National Security as Sexual Regulation, by Gary Kinsman and Patrizia Gentile Awfully Devoted Women: Lesbian Lives in Canada, 1900-65, by Cameron Duder Judging Homosexuals: A History of Gay Persecution in Quebec and France, by Patrice Corriveau Sex Work: Rethinking the Job, Respecting the Workers, by Colette Parent, Chris Bruckert, Patrice Corriveau, Maria Nengeh Mensah, and Louise Toupin Selling Sex: Experience, Advocacy, and Research on Sex Work in Canada, edited by Emily van der Meulen, Elya M.